John Locke and the Share of Land

Sections 36-51 of John Locke's 2d Treatise on Government: “Of Civil Government” (the last half of Chapter V "Of Property") has one main theme: land by itself, without labor, produces relatively little. (You can see the text of those sections at the end of this post.) John Locke is at pains to minimize the importance of land by itself because the doubtful basis of the original ownership of land to which current legal ownership harks back is one of the weakest points of his effort to derive ownership of whatever is owned from people's ownership of themselves.

In the beginning of Chapter V, John Locke's case for a labor theory of property relies on land contributing relatively little to production relative to labor. The last half of Chapter V, though ostensibly repeating that message, also functions as an argument that land by itself is relatively unimportant, so that even if John Locke's labor theory of property has holes in it, the gravity of that flaw in his theory is not that great.

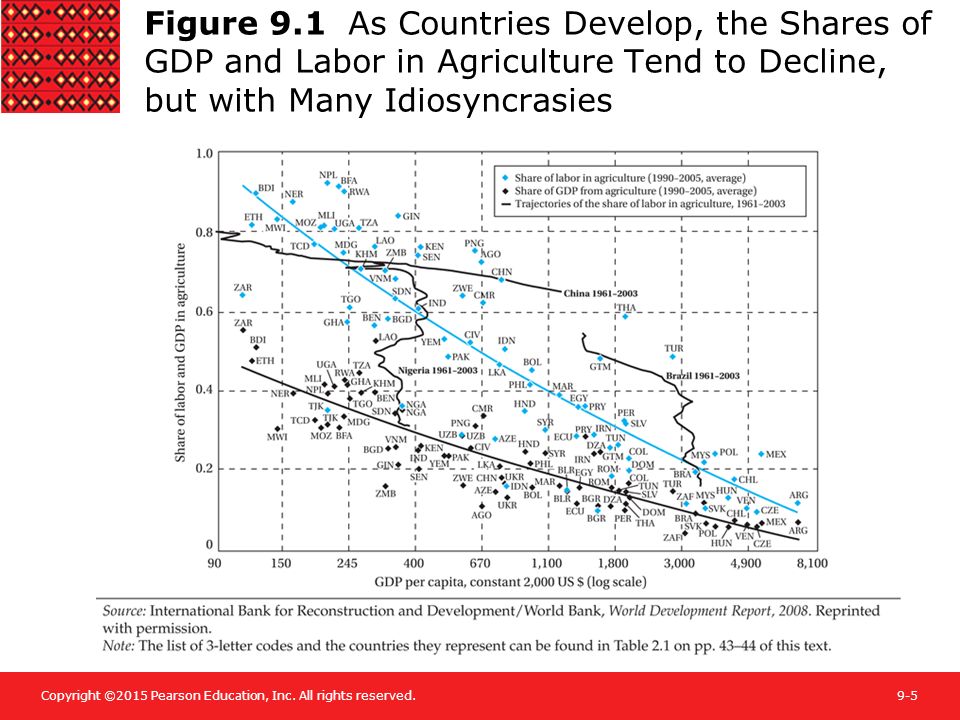

There is one way in which John Locke is just wrong. As David Ricardo later pointed out, in crowded countries that have relatively low agricultural yields, land rents go up. This is of considerable practical relevance in the world today. The United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization reports:

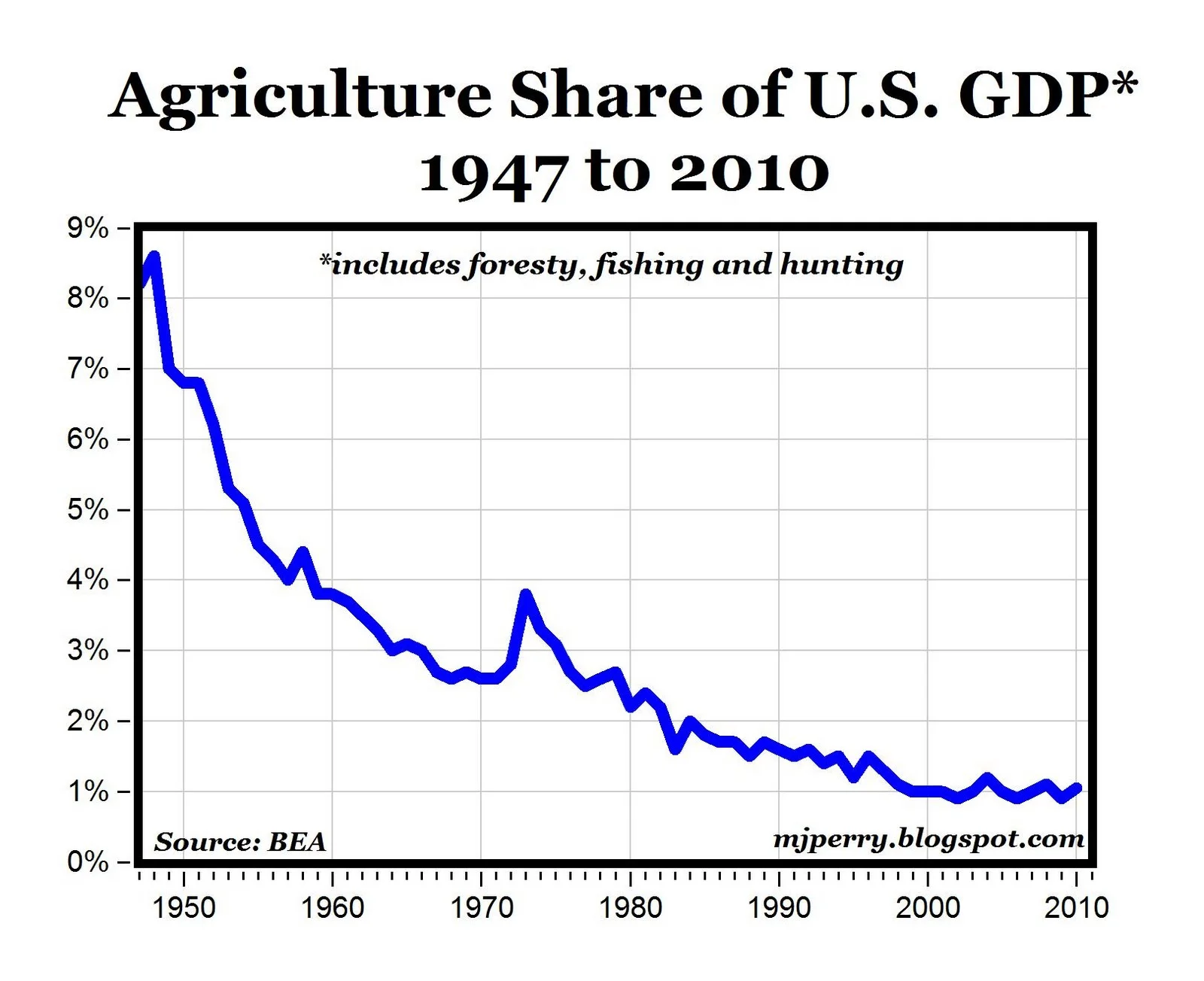

- "Agriculture merely contributes 3 percent to global GDP

- This is one third of the contribution a few decades ago

- However, more than 25 percent of GDP is derived from agriculture in many least developed countries"

However, in countries with high-yielding advanced agriculture, John Locke is not too far off in the world today. Economists calculate "land's share of GDP" by looking at rents to land divided by GDP. The idea is that the amount people pay to rent land is a good guide to how valuable that land is in production.

However, total land rents as a share of GDP are a big overstatement of the implicit contribution of raw land to GDP. First, agricultural land is often improved by being cleared of trees and weeds, and sometimes by the digging of irrigation ditches.

Second, even leaving aside the value of the buildings directly on top, non-agricultural land is usually valuable because of its proximity to other buildings on land nearby and the people who are often in those buildings on land nearby. For many people, the most attractive thing in relation to residential land is to be like the Emperor of Japan: having a big open estate in the middle of a highly populated, commercially impressive city like Tokyo. To give an American example that is not literally about land, I have read that (at least in normal times) some of the most desirable offices in the country are tiny offices that happen to be close to the Oval Office in the White House. The realtor's motto of "Location, location, location" is not really about location itself but about relative location: what other buildings are you near to. The closest thing to an exception is beach property, but even beach property far from any populated area is of modest expense compared to otherwise unremarkable pieces of land in the heart of giant cities.

To estimate raw land's share of GDP, I will overestimate by leaving in the productive value of improvements, but I will leave out the attraction of "location, location, location" relative to buildings on nearby land by applying the average rent of agricultural land to all the land in the Continental US plus Hawaii. In equilibrium, absent government subsidies or other government-induced distortion, most agriculture takes place on land that doesn't have a big urban location premium. So agricultural rents are a reasonable way to get closer to the value of land absent an urban location premium. One can get an upper bound on agricultural rents as a fraction of GDP by looking at the total agricultural share of GDP, which includes contribution of labor and capital as well. The graphs at the top give some idea there.

With all the ag econ departments in existence, I thought it would be easier to google up nice graphs of agricultural rent as a fraction of GDP, but it wasn't so easy. Here is where I got my rent per acre figures:

I will use this figure even for urban land in order to strip out the "location, location, location" part of urban land rents. I will use the term "agriculture-equivalent rent" for this imputation.

Leaving out Alaska, where most of the land is unsuitable for agriculture (and so would have a very cheap rent for agricultural purposes), the US has about 1.9 billion acres total, based on this source. Let me approximate by treating the agriculture-equivalent rent in Alaska as zero and the agriculture-equivalent rent for the rest of the US as $140 an acre, based on the graph just above. Multiplying 1.9 billion acres by a rent of $140 per acre implies total agriculture-equivalent rent of $266 billion per year. Rounding down, nominal US GDP in 2012 was $16 trillion (see FRED), so agriculture-equivalent rent is about 1.7% of GDP. That is, indeed, a relatively small fraction of the value of GDP.

Coda A. Given that the Second Treatise was published in 1689, John Locke deals well with the confusing fact that, while the rents of agricultural land are a small fraction of GDP, the purchase prices of agricultural land would be substantial relative to GDP. This is because ownership of a piece of land entitles one to the rents on that land for many years. John Locke didn't have the tools to talk clearly about the capitalized value of land relative to rents, but I interpret his discussion of the importance of money for land values as a gesture toward the capitalization of rents. He talks about the durability of money, but the real point is the durability of the land itself. (See below for all of this.)

According to William Larson of the Bureau of Economic Analysis, all US land was worth $23 trillion in current prices in 2009, which was 23/14.5 or about 159% of GDP in 2009. William Larson also writes that "Agricultural land is 47% of the total land area of the U.S., while consisting of 8% of its total value." That implies that agricultural land was worth about 13% of one year's worth of GDP in 2009. The value as a fraction of GDP will have fluctuated since then, but it is probably somewhere around there now.

Coda B. While the rents from raw land can be taxed away without distortion in Henry George fashion, it is not at all clear that the "location, location, location" portion of the urban land rent can be taxed without distortion, since it might discourage developers from trying to put together useful urban combinations. Note that this "location, location, location" portion of the rent is still distinct from the rent of the building on top of the land. Developers try to internalize the value of having buildings on land nearby by also owning the land nearby and building on it or otherwise developing it in ways they hope are appealing. To the extent they create some of the "location, location, location" value by making a piece of land an attractive location through building nearby, they should be rewarded for this activity. Taxing away the "location, location, location" value takes away that reward.

Coda C. One of the things much scarcer and more expensive than land to be owned within an existing political system is land that is politically virgin land that would allow one to do a new political experiment without going through the cost of a rebellion. John Locke would be sympathetic to the desire for politically virgin land. Looking toward the future, there is the possibility that water, rock and metal from asteroids will enable people to construct space stations that can serve as politically virgin "land." If so, we may see more political experiments in the future.

Don't miss other John Locke posts. Links at "John Locke's State of Nature and State of War."

In particular, here are other John Locke posts about land and land ownership:

- On John Locke's Labor Theory of Property

- John Locke: Property in the State of Nature

- Private Property Reduces Decision-Making Costs

- John Locke on How Things That Are No One's Property Become Someone's Property

- John Locke on Diminishing Marginal Utility as a Limit to Legitimately Claiming Works of Nature as Property

- John Locke's Song of Praise for Work

- John Locke Off Base with His Assumption That There Was Plenty of Land at the Time of Acquisition

- John Locke: Land Title is Needed to Protect Buildings and Improvements from Expropriation

- John Locke Pretends Land Ownership Goes Back to the Original Peopling of the Planet

§. 36. The measure of property nature has well set by the extent of men’s labour and the conveniences of life; no man’s labour could subdue, or appropriate all; nor could his enjoyment consume more than a small part; so that it was impossible for any man, this way, to intrench upon the right of another, or acquire to himself a property to the prejudice of his neighbour, who would still have room for as good, and as large a possession (after the other had taken out his) as before it was appropriated. This measuredid confine every man’s possession to a very moderate proportion, and such as he might appropriate to himself, without injury to any body, in the first ages of the world, when men were more in danger to be lost, by wandering from their company in the then vast wilderness of the earth, than to be straitened for want of room to plant in. And the same measure may be allowed still without prejudice to any body, as full as the world seems: for supposing a man, or family, in the state they were at first peopling of the world by the children of Adam, or Noah; let him plant in some inland, vacant places of America, we shall find that the possessions he could make himself upon the measures we have given, would not be very large, nor, even to this day, prejudice the rest of mankind, or give them reason to complain, or think themselves injured by this man’s encroachment, though the race of men have now spread themselves to all the corners of the world, and do infinitely exceed the small number was at the beginning. Nay, the extent of ground is of so little value, without labour, that I have heard it affirmed, that in Spain itself a man may be permitted to plough, sow and reap, without being disturbed, upon land he has no other title to, but only his making use of it. But, on the contrary, the inhabitants think themselves beholden to him, who, by his industry on neglected, and consequently waste land, has increased the stock of corn, which they wanted. But be this as it will, which I lay no stress on; this I dare boldly affirm, that the same rule of propriety, (viz.) that every man should have as much as he could make use of, would hold still in the world, without straitening any body: since there is land enough in the world to suffice double the inhabitants, had not the invention of money, and the tacit agreement of men to put a value on it, introduced by consent, larger possessions, and a right to them; which, how it has done, I shall by and by shew more at large.

§. 37. This is certain, that in the beginning, before the desire of having more than man needed had altered the intrinsic value of things, which depends only on their usefulness to the life of man: or had agreed that a little piece of yellow metal, which would keep without wasting or decay, should be worth a great piece of flesh, or a whole heap of corn; though men had a right to appropriate, by their labour, each one to himself, as much of the things of nature, as he could use: yet this could not be much, nor to the prejudice of others, where the same plenty was still left to those who would use the same industry. To which let me add, that he, who appropriates land to himself by his labour, does not lessen, but increase the common stock of mankind: for the provisions serving to the support of human life, produced by one acre of inclosed and cultivated land, are (to speak much within compass) ten times more than those which are yielded by an acre of land of an equal richness lying waste in common. And therefore he that incloses land, and has a greater plenty of the conveniences of life from ten acres, than he could have from an hundred left to nature, may truly be said to give ninety acres to mankind: for his labour now supplies him with provisions out of ten acres, which were but the product of an hundred lying in common. I have here rated the improved land very low, in making its product but as ten to one, when it is much nearer an hundred to one: for I ask, whether in the wild woods and uncultivated waste of America, left to nature, without any improvement, tillage or husbandry, a thousand acres yield the needy and wretched inhabitants as many conveniences of life, as ten acres of equally fertile land do in Devonshire, where they are well cultivated.

Before the appropriation of land, he who gathered as much of the wild fruit, killed, caught, or tamed, as many of the beasts, as he could; he that so employed his pains about any of the spontaneous products of nature, as any way to alter them from the state which nature put them in, by placing any of his labour on them, did thereby acquire a propriety in them: but if they perished, in his possession, without their due use; if the fruits rotted, or the venison putrified, before he could spend it, he offended against the common law of nature, and was liable to be punished; he invaded his neighbour’s share; for he had no right farther than his use called, for any of them, and they might serve to afford him conveniences of life.

§. 38. The same measures governed the possession of land too: whatsoever he tilled and reaped, laid up and made use of, before it spoiled, that was his peculiar right; whatsoever he enclosed, and could feed, and make use of, the cattle and product was also his. But if either the grass of his inclosure rotted on the ground, or the fruit of his planting perished without gathering, and laying up, this part of the earth, notwithstanding his inclosure, was still to be looked on as waste, and might be the possession of any other. Thus, at the beginning, Cain might take as much ground as he could till, and make it his own land, and yet leave enough to Abel’s sheep to feed on; a few acres would serve for both their possessions. But as families increased, and industry enlarged their stocks, their possessions enlarged with the need of them; but yet it was commonly without any fixed property in the ground they made use of, till they incorporated, settled themselves together, and built cities; and then, by consent, they came in time, to set out the bounds of their distinct territories, and agree on limits between them and their neighbours; and by laws within themselves, settled the properties of those of the same society: for we see, that in that part of the world which was first inhabited, and therefore like to be best peopled, even as low down as Abraham’s time, they wandered with their flocks, and their herds, which was their substance, freely up and down; and this Abraham did, in a country where he was a stranger. Whence it is plain, that at least a great part of the land lay in common; that the inhabitants valued it not, nor claimed property in any more than they made use of. But when there was not room enough in the same place, for their herds to feed together, they by consent, as Abraham and Lot did, Gen. xiii. 5. separated and enlarged their pasture, where it best liked them. And for the same reason Esau went from his father, and his brother, and planted in mount Seir, Gen. xxxvi. 6.

§. 39. And thus, without supposing any private dominion, and property in Adam, over all the world, exclusive of all other men, which can no way be proved, nor any one’s property be made out from it; but supposing the world given, as it was, to the children of men in common, we see how labour could make men distinct titles to several parcels of it, for their private uses; wherein there could be no doubt of right, no room for quarrel.

§. 40. Nor is it so strange, as perhaps before consideration it may appear, that the property of labour should be able to over-balance the community of land: for it is labourindeed that puts the difference of value on every thing; and let any one consider what the difference is between an acre of land planted with tobacco or sugar, sown with wheat or barley, and an acre of the same land lying in common, without any husbandry upon it, and he will find, that the improvement of labour makes the far greater part of the value. I think it will be but a very modest computation to say, that of the products of the earth useful to the life of man, nine-tenths are the effects of labour: nay, if we will rightly estimate things as they come to our use, and cast up the several expences about them, what in them is purely owing to nature, and what to labour, we shall find, that in most of them ninety-nine hundredths are wholly to be put on the account of labour.

§. 41. There cannot be a clearer demonstration of any thing, than several nations of the Americans are of this, who are rich in land, and poor in all the comforts of life; whom nature having furnished as liberally as any other people, with the materials of plenty, i. e.a fruitful soil, apt to produce in abundance, what might serve for food, raiment, and delight; yet for want of improving it by labour, have not one hundredth part of the conveniences we enjoy; and a king of a large and fruitful territory there, feeds, lodges, and is clad worse than a day-labourer in England.

§. 42. To make this a little clearer, let us but trace some of the ordinary provisions of life through their several progresses, before they come to our use, and see how much they receive of their value from human industry. Bread, wine and cloth, are things of daily use, and great plenty; yet notwithstanding, acorns, water and leaves, or skins, must be our bread, drink and cloathing, did not labour furnish us with these more useful commodities: for whatever bread is more worth than acorns, wine than water, and clothor silk, than leaves, skins or moss, that is wholly owing to labour and industry; the one of these being the food and raiment which unassisted nature furnishes us with; the other, provisions which our industry and pains prepare for us, which how much they exceed the other in value, when any one hath computed, he will then see how much labour makes the far greatest part of the value of things we enjoy in this world: and the ground which produces the materials, is scarce to be reckoned in, as any, or at most, but a very small part of it; so little, that even amongst us, land that is left wholly to nature, that hath no improvement of pasturage, tillage, or planting, is called, as indeed it is, waste; and we shall find the benefit of it amount to little more than nothing.

This shews how much numbers of men are to be preferred to largeness of dominions; and that the increase of lands, and the right employing of them, is the great art of government: and that prince, who shall be so wise and godlike, as by established laws of liberty to secure protection and encouragement to the honest industry of mankind, against the oppression of power and narrowness of party, will quickly be too hard for his neighbours: but this by the by. To return to the argument in hand,

§. 43. An acre of land, that bears here twenty bushels of wheat, and another in America, which with the same husbandry, would do the like, are, without doubt, of the same natural intrinsic value: but yet the benefit mankind receives from one in a year, is worth 5l. and from the other possibly not worth a penny, if all the profit an Indian received from it were to be valued and sold here; at least I may truly say, not one thousandth. It is labour then which puts the greatest part of value upon land, without which it would scarcely be worth any thing: it is to that we owe the greatest part of all its useful products; for all that the straw, bran, bread, of that acre of wheat, is more worth than the product of an acre of as good land, which lies waste, is all the effect of labour: for it is not barely the ploughman’s pains, the reaper’s and thresher’s toil, and the baker’s sweat, is to be counted into the bread we eat; the labour of those who broke the oxen, who digged and wrought the iron and stones, who felled and framed the timber employed about the plough, mill, oven, or any other utensils, which are a vast number, requisite to this corn, from its being seed to be sown to its being made bread, must all be charged onthe account of labour, and received as an effect of that: nature and the earth furnished only the almost worthless materials, as in themselves. It would be a strange catalogue of things, that industry provided and made use of, about every loaf of bread, before it came to our use, if we could trace them; iron, wood, leather, bark, timber, stone, bricks, coals, lime, cloth, dying drugs, pitch, tar, masts, ropes, and all the materials made use of in the ship, that brought any of the commodities made use of by any of the workmen, to any part of the work; all which it would be almost impossible, at least too long to reckon up.

§. 44. From all which it is evident, that though the things of nature are given in common, yet man, by being master of himself, and proprietor of his own person, and the actions or labour of it, had still in himself the great foundation of property; and that, which made up the great part of what he applied to the support or comfort of his being, when invention and arts had improved the conveniences of life, was perfectly his own, and did not belong in common to others.

§. 45. Thus labour, in the beginning, gave a right of property, wherever any one was pleased to employ it upon what was common, which remained a long while the far greater part, and is yet more than mankind makes use of. Men, at first, for the most part, contented themselves with what unassisted nature offered to their necessities; and though afterwards, in some parts of the world, (where the increase of people and stock, with the use of money, had made land scarce, and so of some value) the several communitiessettled the bounds of their distinct territories, and by laws within themselves regulated the properties of the private men of their society, and so, by compact and agreement, settled the property which labour and industry began; and the leagues that have been made between several states and kingdoms, either expressly or tacitly disowning all claim and right to the land in the other’s possession, have, by common consent, given up their pretences to their natural common right, which originally they had to those countries, and so have, by positive agreement, settled a property amongst themselves, in distinct parts and parcels of the earth; yet there are still great tracts of ground to be found, which (the inhabitants thereof not having joined with the rest of mankind, in the consent of the use of their common money) lie waste, and are more than the people who dwell on it do, or can make use of, and so still lie in common; though this can scarce happen amongst that part of mankind that have consented to the use of money.

§. 46. The greatest part of things really useful to the life of man, and such as the necessity of subsisting made the first commoners of the world look after, as it doth the Americans now, are generally things of short duration; such as, if they are not consumed by use, will decay and perish of themselves: gold, silver, and diamonds, are things that fancy or agreement hath put the value on, more than real use, and the necessary support of life. Now of those good things which nature hath provided in common, every one had a right (as hath been said) to as much as he could use, and property in all that he could effect with his labour; all that his industry could extend to, to alter from the state nature had put it in, was his. He that gathered a hundred bushels of acorns or apples, had thereby a property in them, they were his goods as soon as gathered. He was only to look, that he used them before they spoiled, else he took more than his share, and robbed others. And indeed it was a foolish thing, as well as dishonest, to hoard up more than he could make use of. If he gave away a part to any body else, so that it perished not uselessly in his possession, these he also made use of. And if he also bartered away plums, that would have rotted in a week, for nuts that would last good for his eating a whole year, he did no injury; he wasted not the common stock; destroyed no part of the portion of goods that belonged to others, so long as nothing perished uselessly in his hand. Again, if he would give his nuts for a piece of metal, pleased with its colour; or exchange his sheep for shells, or wool for a sparkling pebble or a diamond, and keep those by him all his life, he invaded not the right of others, he might heap up as much of these durable things as he pleased: the exceeding of the bounds of his just property not lying in the largeness of his possession, but the perishing of any thing uselessly in it.

§. 47. And thus came in the use of money, some lasting thing that men might keep without spoiling, and that by mutual consent men would take in exchange for the truly useful, but perishable supports of life.

§. 48. And as different degrees of industry were apt to give men possessions in different proportions, so this invention of money gave them the opportunity to continue and enlarge them: for supposing an island, separate from all possible commerce with the rest of the world, wherein there were but an hundred families, but there were sheep, horses, and cows, with other useful animals, wholsome fruits, and land enough for corn for a hundred thousand times as many, but nothing in the island, either because of its commonness, or perishableness, fit to supply the place of money; what reason could any one have there to enlarge his possessions beyond the use of his family, and a plentiful supply to its consumption, either in what their own industry produced, or they could barter for like perishable, useful commodities with others? Where there is not some thing, both lasting and scarce, and so valuable to be hoarded up, there men will be apt to enlarge their possessions of land, were it never so rich, never so free for them to take: for I ask, what would a man value ten thousand, or an hundred thousand acres of excellent land, ready cultivated, and well stocked too with cattle, in the middle of the inland parts of America, where he had no hopes of commerce with other parts of the world, to draw money to him by the sale of the product? It would not be worth the inclosing, and we should see him give up again to the wild common of nature, whatever was more than would supply the conveniences of life to be had there for him and his family.

§. 49. Thus in the beginning all the world was America, and more so than that is now; for no such thing as money was any where known. Find out something that hath the use and value of money amongst his neighbours, you shall see the same man will begin presently to enlarge his possessions.

§. 50. But since gold and silver, being little useful to the life of man in proportion to food, raiment, and carriage, has its value only from the consent of men, whereof labour yet makes, in great part, the measure, it is plain, that men have agreed to a disproportionate and unequal possession of the earth, they having, by a tacit and voluntary consent, found out a way how a man may fairly possess more land than he himself can use the product of, by receiving in exchange for the overplus gold and silver, which may be hoarded up without injury to any one; these metals not spoiling or decaying in the hands of the possessor. This partage of things in an inequality of private possessions, men have made practicable out of the bounds of society, and without compact, only by putting a value on gold and silver, and tacitly agreeing in the use of money: for in governments, the laws regulate the right of property, and the possession of land is determined by positive constitutions.

§. 51. And thus, I think, it is very easy to conceive, without any difficulty, how labour could at first begin a title of property in the common things of nature, and how the spending it upon our uses bounded it. So that there could then be no reason of quarrelling about title, nor any doubt about the largeness of possession it gave. Right and conveniency went together; for as a man had a right to all he could employ his labour upon, so he had no temptation to labour for more than he could make use of. This left no room for controversy about the title, nor for incroachment on the right of others; what portion a man carved to himself was easily seen; and it was useless, as well as dishonest, to carve himself too much, or take more than he needed.