How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide

Even with links, it has become hard for me to explain in the 140 characters I have on Twitter how an interested reader should approach reading or listening to what I have to say about eliminating the zero lower bound. This post is meant to meet that need. I hope to keep it updated when I add relevant new posts.

I have organized all my posts on eliminating the zero lower bound on interest rates into categories; a few fall into more than one category. Within each category, they appear in chronological order, earliest to most recent. (Let me know if I have left out a relevant post.) The last category below is for posts that are in part about some other topic, but that contain a brief appeal for eliminating the zero lower bound and putting negative interest rates in the monetary policy toolkit–brief enough to copy out below.

If you have only 5 minutes, the video of the CEPR interview with me that will catch your eye below is a great place to start. A little further down is a video of my 20-minute talk at Brookings.

If you want academic policy papers, please turn to these three:

“Negative Interest Rate Policy as Conventional Monetary Policy” has been translated into German. These papers incorporate many (though not all) of the arguments in the other links below.

Note: some of the most important posts below have been translated into Japanese here, thanks to the efforts of Makoto Shimizu. Makoto has also written a book on negative interest rate policy in Japanese that you can find here. Suparit Suwanik has begun to translate key posts into Thai.

The Core Argument

How Subordinating Paper Money to Electronic Money Can End Recessions and End Inflation

Could the UK be the First Country to Adopt Electronic Money?

Larry Summers Just Confirmed that He is Still a Heavyweight on Economic Policy

Interview by Dylan Matthews for Wonkblog: “Can We Get Rid of Inflations and Recessions Forever?”

Gather ‘round, Children, Here’s How to Heal a Wounded Economy

Paul Krugman Graphs How the Zero Lower Bound Constrains Monetary Policy

On the Need for Large Movements in Interest Rates to Stabilize the Economy with Monetary Policy

CEPR Interview: Miles Kimball–Practical Details of Negative Interest Rates (the 5 minute video of the interview itself is also just below)

Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound: The IMF Working Paper

Greg Robb: Fed Officials Seem Ready to Deploy Negative Interest Rates in Next Crisis

Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound and Electronic Money: The AEA Meeting Presentation

Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates

What is the Effective Lower Bound on Interest Rates Made Of?

The Political Perils of Not Using Deep Negative Rates When Called For

The Supply and Demand for Paper Currency When Interest Rates Are Negative

Markus Brunnermeier and Yann Koby's "Reversal Interest Rate"

Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball—Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide

Give Central Banks Independence and New Political Pressures to Balance the Old Ones

Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball on Negative Interest Rates and Inflation—IMF Podcasts

Explanations of Negative Interest Rates in Alternative Media

Dylan Matthews: The Only Kids’ Book You Need to Understand the Federal Reserve

The Story of Ben the Money Master (read-aloud YouTube video)

The Story of Ben the Money Master–Operatic Ballad Version (YouTube video)

Operational Details for Eliminating the Zero Lower Bound

How to Set the Exchange Rate Between Paper Currency and Electronic Money

David Beckworth and Miles Kimball: The Padding on Top of the Zero Lower Bound

Interview by Dylan Matthews for Wonkblog: “Can We Get Rid of Inflations and Recessions Forever?”

Why Scott Fullwiler Misses the Point in “Why Negative Nominal Interest Rates Miss the Point”

The Swiss National Bank Means Business with Its Negative Rates

Negative Interest Rates and Financial Stability: Alexander Trentin Interviews Miles Kimball

JP Koning and Miles Kimball Discuss Negative Interest Rate Alternatives

However Low Interest Rates Go, The IRS Will Never Act Like a Bank

Alexander Trentin: Negative Interest Rates and the Swan Song of Cash

Why a Weaker Effect of Exchange Rates on Net Exports Doesn’t Weaken the Power of Monetary Policy

Luke Kawa: How Central Banks Gained More Control Over the World’s Major Currencies

The Swiss National Bank and Bank of Japan’s New Tool to Block Massive Paper Currency Storage

Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates

Ben Bernanke: Maybe the Fed Should Keep Its Balance Sheet Large

Ben Bernanke: Negative Interest Rates are Better than a Higher Inflation Target

The Bank of Japan Renews Its Commitment to Do Whatever It Takes

How Negative Rates are Making the Swiss Want to Pay Their Taxes Earlier

Paper Currency Deposit Fees as Unrealized Interest Equivalents

Eric Lonergan and Megan Greene: Dual Interest Rates Give Central Banks Limitless Firepower

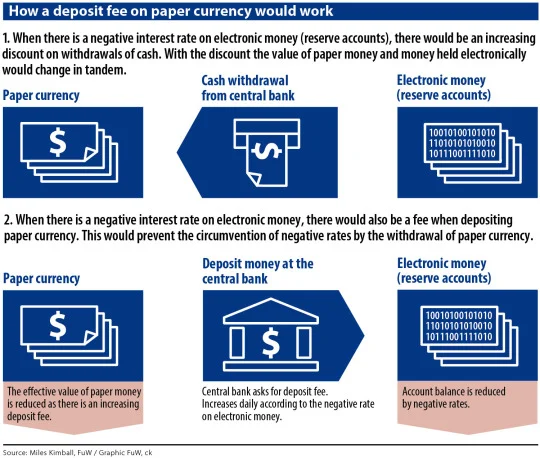

The graphic above is a translation of the one here, graciously provided by Finanz und Wirtschaft through the good offices of Alexander Trentin. Used by permission.

Potential Side Effects

Mark Carney: Central Banks are Being Forced Into Low Interest Rates by the Supply Side Situation

Responding to Negative Coverage of Negative Rates in the Financial Times

Legal Issues

Legal Issues Relevant for the Transition to Electronic Money

Greg Shill: So What Are the Federal Reserve’s Legal Constraints, Anyway?

Greg Shill: Does the Fed Have the Legal Authority to Buy Equities?

However Low Interest Rates Go, The IRS Will Never Act Like a Bank

How to Keep a Zero Interest Rate on Reserves from Creating a Zero Lower Bound

Paper Currency Deposit Fees as Unrealized Interest Equivalents

Comparison of Negative Interest Rates to Other Tools for Stimulating the Economy

Monetary vs. Fiscal Policy: Expansionary Monetary Policy Does Not Raise the Budget Deficit

How and Why to Avoid Mixing Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy

Is the Bank of Japan Succeeding in Its Goal of Raising Inflation?

Japan Should Be Trying Out a Next Generation Monetary Policy

Alex Rosenberg Interviews Miles Kimball on the Responsiveness of Monetary Policy to New Information

Gauti Eggertsson and Miles Kimball: Quantitative Easing vs. Forward Guidance

Narayana Kocherlakota Advocates Negative Rates and Criticizes the Conduct of US Fiscal Policy

Ezra Klein Interviews Ben Bernanke about Miles Kimball’s Proposal to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound

Nick Rowe on Monetary Dominance (direct link)

Denmark's Brilliant Stabilization Policy (storified tweets)

Japan Shows How to Do Interest Rate Targets for Long-Term Bonds Instead of Quantity Targets

FocusEconomics: How and When will the Next Financial Crisis Happen?—26 Experts Weigh In

News and Trends

Neil Irwin: Europe Likely to Get Negative Interest Rates. What Does That Even Mean?

Ken Rogoff: Paper Money is Unfit for a World of High Crime and Low Inflation

Tomas Hirst on the Decline in the Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate

The Wall Street Journal’s Big Page One Monetary Policy Mistake

Brian Blackstone Doubles Down on a Big Mistake in Reporting on Monetary Policy

Could the European Central Bank be Preparing to Break Through the Zero Lower Bound?

Joe Weisenthal on Willem Buiter’s List of 3 Ways to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound

Matthew Yglesias on the Need to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound to Avoid Secular Stagnation

Hojoon Kim: Will Mobile Payment Apps Replace Cash in the Near Future?

Swiss Pioneers! The Swiss as the Vanguard for Negative Interest Rates

Matthew Yglesias on Negative Interest Rates in Europe (direct link)

Jennifer Ryan on Andrew Haldane: “The UK’s Subversive Central Banker”

Radical Banking: The World Needs New Tools to Fight the Next Recession

Bank of England Chief Economist Andrew Haldane Explains How to Break Through the Zero Lower Bound

Brian Blackstone: Deflation Holds No Terrors for Those Who Know How to Use Negative Interest Rates

Paul Taylor and Balazs Koranyi: ECB Rate Setters Converge on December Deposit Rate Cut

Mike Bird on Negative Interest Rate Policy | Business Insider

The Wall Street Journal Gets It Right On Negative Interest Rate Policy, Thanks to Tommy Stubbington

CNBC.com: Bank of Japan Adopts Negative Interest Rate Policy

Reporting on Japan’s Move to Negative Interest Rates (+ German translation here)

JP Morgan’s Michael Feroli, Malcolm Barr, Bruce Kasman and David Mackie On Board for Negative Rates

Joshua Zumbrun Talks About Larry Summers’s Call to Heed Ken Rogoff and Eliminate the $100 Bill

Makoto Shimizu Reports on the Bank of Japan’s New Tool to Block Massive Paper Currency Storage

The Globe and Mail Gets It Right on Negative Interest Rate Policy, Thanks to Ian McGugan

Scott Sumner–The Media’s Blind Spot: Negative Interest on Reserves

Negative Interest on Deposits at the National Bank of Hungary; Randy Kroszner on Negative Rates

Is the Swiss National Bank Ready to Limit Convertibility of Electronic Money to Paper Currency?

Leon Berkelman’s Report on the Brookings Conference on Negative Interest Rate Policy

Narayana Kocherlakota: Negative Interest Rates Are Nothing to Fear

Lauren Razavi: India Just Flew Past Us in the Race to E-Cash

Brian Knight: Federalism and Federalization on the Fintech Frontier (direct link)

Jeffrey Rogers Hummel's Review of Ken Rogoff’s The Curse of Cash and Ken's Response

Deutsche Bank Research: Interesting Developments Regarding Potential Yellen Replacement

Narayana Kocherlakota: Negative Rates are the Cleaner Economic Solution

Chris Hedeminger: Graphs Showing the Dominance of $100 Bills within US Paper Currency

Greg Ip—The Fed's Choice: Overheat the Economy or Give Up Its 2% Per Year Inflation Target

Brittany Jones-Cooper: These Countries Have Gone Mostly Cashless

David Beckworth—The Safe Asset Problem is Back: Negative Interest Rate Edition

Why America Needs Marvin Goodfriend on the Federal Reserve Board

Greg Ip: A Decade After Bear’s Collapse, the Seeds of Instability Are Germinating Again

Alexander Trentin Interviews Miles Kimball on Next Generation Monetary Policy

Lars Christensen on Why the Natural Interest Rate Has Declined

Reza Moghadam Flags 'Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions' in the Financial Times

Is the Bitcoin Algorithm a 'Robot Central Bank' or is Bitcoin Free-Market Money?

A New Advocate for Negative Interest Rate Policy: Donald Trump

Pressure on the Fed from the Market and Trump for Negative Rates

Radio and Video Interaction

History of Thought and Economic History

More on the History of Thought for Negative Nominal Interest Rates

Willem Buiter: The Wonderful World of Negative Nominal Interest Rates, Again

JP Koning: Does the Zero Lower Bound Exist Thanks to the Government’s Paper Currency Monopoly?

Henrik Jensen: Willem [Buiter] and the Negative Nominal Interest Rate

JP Koning: The Zero Lower Bound as an Instance of Gresham’s Law in Reverse

Ken Rogoff: Paper Money is Unfit for a World of High Crime and Low Inflation

Did the Gold Standard Help Bring Hitler to Power? (Twitter Round Table)

Stephen Cechetti and Kermit Schoenholtz: Why a Gold Standard is Bad

Silvio Gesell's Plan for Negative Nominal Interest Rates Meets the Mormons

Q&A, Discussion and Rebuttal

Time for the Paperless Revolution? Tomas Hirst Interviews Miles about Electronic Money

Miles Kimball and Scott Sumner: Monetary Policy, the Zero Lower Bound and Madison, Wisconsin

Interview by Joseph Sotinel for the French Website BFMBusiness about Electronic Money

Q&A on the Swiss National Bank’s Move to Negative Interest Rates

Negative Interest Rates and Financial Stability: Alexander Trentin Interviews Miles Kimball

JP Koning and Miles Kimball Discuss Negative Interest Rate Alternatives

Is It a Problem for Negative Interest Rate Policy If People Hang On to Their Paper Currency?

Storified Twitter Discussions

Twitter Round Table on Our Disastrous Policy of Pegging Paper Currency at Par

Gold, Electronic Money, and the Determinants of the Prices of Storable Commodities from the Ground

Which is More Radical? Electronic Money or a Higher Inflation Target?

Can Electronic Money Stimulate the Economy Even When Banks are Running Scared?

Doubting Tomas: Electronic Money in an Open Economy with Wounded Banks

Legal Counterfeiting as a Way to Enforce a Ban on Paper Currency

A Bit of Personal History of Thought: Zero Lower Bound-->Quantitative Easing-->Electronic Money

JP Koning and David Beckworth on Negative Interest Rates in the Repo Market

The Twitter Campaign for Repealing the Zero Lower Bound: September 2013

Daniel Altman and Miles Kimball on the Long-Run Target for Inflation

Preaching in the Temple: Presenting "Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound" at the Fed

Matthew C. Klein and Miles Kimball on the Effects of Negative Interest Rates on Savers

Diego Espinosa and Miles Kimball on Bitcoin and Electronic Money

Q&A about Negative Interest Rates--The Centre for Monetary Advancement and Miles Kimball

Are Central Banks Scared to Admit that the Zero Lower Bound is a Policy Choice, Not a Law of Nature?

Are Negative Interest Rates a Drug That Requires Ever-Increasing Doses?

Europe Needs Negative Rates, Higher Equity Requirements, Balanced Budgets and Supply-Side Reform

Twitter Roundtable on the Power of Negative Interest Rates Compared to Other Stimulative Policies

Does Economic Stability Inevitably Lead to Financial Fragility?

Eric Lonergan and Miles Kimball Discuss the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates

Sticky Prices, Sticky Inflation and the Cost of Inflation as Reflections of Cognitive Costs

Negative Rate Policy in Switzerland, December 2014-September 2016

Debating Higher Capital Requirements in the Light of the End of the Zero Lower Bound

Will Negative Rates Cause Malinvestment? Will They Harm Banks?

Miles Kimball, Roger Farmer, Stephen Williamson and Joe Little on Recent Japanese Monetary Policy

Reactions

Reihan Salam: “Miles Kimball on How Electronic Currency Could Yield True Price Stability”

Tomas Hirst: Beware False Equivalence Between Depositor Haircuts and Negative Interest Rates

Matt Griffin: How Paul Krugman Convinced Me to Support Miles Kimball’s E-Money Idea

The Institute for Social Research Summarizes the Argument for Electronic Money

David Beckworth: Has The Natural Interest Rate Been Negative for the Past Five Years?

David Beckworth and Amir Sufi: What Caused The Great Recession? Household Deleveraging or ZLB?

Kim Schoenholtz and Stephen Cecchetti: Has Paper Money Outlived Its Purpose?

Alexander Trentin: “Japan, It’s Time to Finally Overthrow Cash!”

Oliver Davies and Miles Kimball on a Method for Nominal GDP Targeting

Michael Reddell: The Zero Lower Bound and Miles Kimball’s Visit to New Zealand

Leon Berkelmans: Time to Consider Negative Interest Rates to Boost Growth

Oliver Davies Argues for Negative Interest Rates instead of Helicopter Drops

Mike Bird on Negative Interest Rate Policy | Business Insider

Friends and Sparring Partners: The Skyline from My Corner of the Blogosphere

Brief Appeals for Eliminating the Zero Lower Bound, Short Enough to Copy Out Here

It is the fear of massive storage of paper currency that prevents the US Federal Reserve and other central banks from cutting short-term rates as far below zero as necessary to bring full recovery. (If electronic dollars, yen, euros and pounds are treated as “the real thing”—the yardsticks for prices and contracts—it is OK for people to continue using paper currency as they do now, as long as the value of paper money relative to electronic money goes down fast enough to keep people from storing large amounts of paper money as a way of circumventing negative interest rates on bank accounts.) As I argued in “Could the UK be the first country to adopt electronic money,” the low interest rates that electronic money allows would stimulate not only business investment and home building, but exports as well—something that would lead to a virtuous domino effect as the adoption of an electronic money standard by one country led to its adoption by others to avoid trade deficits. If I were writing that column now, I would be asking if Japan could be the first country to adopt electronic money, since Japan’s new prime minister Shinzo Abe is calling for a new direction in monetary policy. For the Euro zone, I argue in “How the electronic deutsche mark can save Europe” that electronic money is not only the way to achieve full recovery, but the solution to its debt crisis as well….

Franklin Roosevelt famously said:

“The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

We are at such a moment again. The usual remedies have failed. It is time to try something new.

… it is an even more important mistake to think that monetary policy can’t cut short-term interest rates below zero. Weisenthal quotes a post on Barnejek’s blog, “Has Britain Finally Cornered Itself?” that illustrates the faulty thinking I’m talking about:

“Before I start, however, I would like to thank the British government for conducting a massive social experiment, which will be used in decades to come as a proof that a tight fiscal/loose monetary policy mix does not work in an environment of a liquidity trap. We sort of knew that from the theory anyway but now we have plenty of data to base that on.”

“Liquidity trap” is code for the inability of the Bank of England to lower interest rates below zero. The faulty thinking is to treat the “liquidity trap” or the “Zero Lower Bound,” as modern macroeconomists are more likely to call it, as if it were a law of nature. _The Zero Lower Bound is not a law of nature! _It is a consequence of treating money in bank accounts and paper currency as interchangeable. As I explain in a series of Quartz columns (1, 2, 3 and 4) and posts on my blog—that is a matter of economic policy and law that can easily be changed. As soon as paper pounds are treated as different creatures from electronic pounds in bank accounts, it is easy to keep paper pounds from interfering with the conduct of monetary policy. In times when the Bank of England needs to lower short-term interest rates below zero, the effective rate of return on paper pounds can be kept below zero by announcing a crawling peg “exchange rate” between paper pounds and electronic pounds that has the paper pounds gradually depreciating relative to electronic pounds.

In his advice for the UK, Weisenthal should either explain why having an exchange rate between paper pounds and pounds in bank accounts is worse than a massive explosion of debt or join me in tilting against a windmill less tilted against. And for those who read Krugman’s columns, it would take a bad memory indeed not to recall that he gives the corresponding advice of stimulus by additional government spending for the US, which faces its own debt problem. I hope Paul Krugman will join me too in attacking the Zero Lower Bound.

“… you shall not crucify mankind on a cross of gold.”

In our time it is not gold that is crucifying the world economy (though some would return us to the problems that were caused by the gold standard), but the unthinking worldwide policy of treating paper currency as interchangeable with money in bank accounts. So for our era, let us say: You shall not crucify humankind on a paper cross.

Although there are a few other economists who might match Bernanke in their monetary policy judgments, through his years at the helm of the Fed, Bernanke has developed an unparalleled skill in explaining and defending controversial monetary policy measures to Congress and to the public. The most important ways in which US monetary policy has fallen short in the last few years are because of the limits Congress has implicitly and explicitly placed on the Fed. Negative interest rates could be much more powerful than quantitative easing, but require a legal differentiation between paper currency and electronic money in bank accounts to avoid massive currency storage that would short-circuit the intended stimulus to the economy.

For the US, the most important point is that using monetary policy to stimulate the economy does not add to the national debt and that even when interest rates are near zero, the full effectiveness of monetary policy can be restored if we are willing to make a legal distinction between paper currency and electronic money in bank accounts—treating electronic money as the real thing, and putting paper currency in a subordinate role. (See my columns, “How paper currency is holding the US recovery back” and “What the heck is happening to the US economy? How to get the recovery back on track.”) As things are now, Ben Bernanke is all too familiar with the limitation on monetary policy that comes from treating paper currency as equivalent to electronic money in bank accounts. He said in his Sept. 13, 2012 press conference:

“If the fiscal cliff isn’t addressed, as I’ve said, I don’t think our tools are strong enough to offset the effects of a major fiscal shock, so we’d have to think about what to do in that contingency.”

Without the limitations on monetary policy that come from our current paper currency policy, the Fed could lower interest rates enough (even into negative territory for a few quarters if necessary) to offset the effects of even major tax increases and government spending cuts.

…the tools currently at the Fed’s disposal plus clearly communicating a nominal GDP target are not enough to get the desired result. The argument goes as follows. Interest rates are the price of getting stuff—goods and services—now instead of later. If people are out of work, we want customers to buy stuff now by having low interest rates. Thinking about short-term interest rates like the usual federal funds rate target that the Fed uses, the timing of the low interest rates matters. If everyone knows we are going to have low short-term interest rates in 2016, then it encourages buying in the whole period between now and 2016 in preference to buying after 2016. But to get the economy out of the dumps, we really want people to buy right now, not spread out their purchases over 2013, 2014, and 2015. The lower we can push short-term interest rates, the more we can focus the extra spending on 2013, so that we can have full recovery by 2014, without overshooting and having _too much _spending in 2015. This is an issue that economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman alludes to recently in a column about Japanese monetary policy.

There is only one problem with pushing the short-term interest rate down far enough to focus extra spending right now when we need it most: the way we handle paper currency. The Fed doesn’t dare try to lower the interest rate it targets below zero for fear of causing people to store massive amounts of currency (which _effectively _earns a zero interest rate). Indeed, most economists, like the Fed, are so convinced that massive currency storage would block the interest rate from going more than a hair below zero that they talk regularly about a zero lower bound on interest rates. The solution is to treat paper currency as a different creature than electronic money in bank accounts, as I discuss in many other columns. (“What Paul Krugman got wrong about Italy’s economy” gives links to other columns on electronic money as well.) If instead of being on a par with electronic money in bank accounts, paper currency is allowed to depreciate in value when necessary, the Fed can lower the short-term interest as far as needed, even if that means it has to push the short-term interest rate below zero

Keeping the Economy on Target

In the current economic doldrums, breaking through the zero lower bound with electronic money is the first step in ensuring that monetary policy can quickly get output back to its natural level. A better paper currency policy puts the ability to lower the Fed’s target interest rate back in the toolkit. That makes it possible for the Fed to get the timing of extra spending by firms and households right to meet a nominal GDP target—hopefully one that has been appropriately adjusted for the rate of technological progress.

The reason I wrote this post is because many people don’t seem to understand that low levels of output lower the net rental rate and therefore lower the short-run natural interest rate. Leaving aside other shocks to the economy, monetary policy will not tend to increase output above its current level unless the interest rate is set below the short-run natural interest rate. That means that the deeper the recession an economy is in, the lower a central bank needs to push interest rates in order to stimulate the economy….

If a country makes the mistake of having a paper currency policy that prevents it from lowering the nominal interest rate below zero, then the MP curve has to flatten out somewhere to the left. (The zero lower bound on the nominal interest rate puts a bound of minus expected inflation on the real interest rate. That makes the floor on the real interest rate higher the lower inflation is.) The lower bound on the MP curve might then make it hard to get the interest rate below the net rental rate (a.k.a. the short-run natural interest rate). In my view, this is what causes depressions. QE can help, but is much less powerful than simply changing the paper currency policy so that the nominal interest rate can be lowered below the short-run natural interest rate, however low the recession has pushed that short-run natural interest rate.

The questions I would like to ask Larry Summers and Janet Yellen are many, but let’s focus on three big ones:

Eliminating the “Zero Lower Bound” on Interest Rates. Given all of the problems that a floor of zero on short-term interest rates causes for monetary policy, what do you think of going to negative short-term interest rates, as I have argued for here and here and here? If we repealed the “zero lower bound” that prevents interest rates from going below zero, there would be no need to rely on the large scale purchases of long-term government debt that are a mainstay of “quantitative easing,” the quasi-promises of zero interest rates for years and years that go by the name of “forward guidance,” or inflation to make those zero rates more potent. Repealing the “zero lower bound” would require dramatic changes in monetary policy (and in particular, a dramatic change in the way we handle paper currency), but wouldn’t that be worth it?

… the Fed’s approach of talk therapy is problematic because it is hard to communicate a monetary policy that is strongly stimulative now but will be less stimulative in the future. As I discussed in a previous column and in the presentation I have been giving to central banks around the world, adjusting short-term interest rates has an almost unique ability to get the timing of monetary policy right. Unfortunately, the US government’s unlimited guarantee that people can earn at least a zero interest rate by holding massive quantities of paper currency stands in the way of simply lowering short-term interest rates….

My own recommendations for the Fed are no secret:

Eliminate the zero-lower bound on nominal interest rates—or at least begin making the case to Congress for that authority

Janet Yellen is Hardly a Dove–She Knows that the US Economy Needs Some Unemployment. There can be serious debates about the long-run inflation target. I have taken the minority position that our monetary system should be adapted so that we can safely have a long-run inflation target of zero…. Nor should anyone be called a hawk and have the honor of being thought to truly hate inflation if they are not willing to do what it takes to safely bring inflation down to zero and keep it there. Letting inflation fall willy-nilly because a serious recession has not been snuffed out as soon as it should have been is no substitute for keeping the economy on an even keel and very gradually bringing inflation down to zero, with all due preparation…. In the last 10 years, America’s economic policy-making apparatus as a whole made at least two big mistakes: not requiring banks to put up more of their own shareholders’ money when they took risks, and not putting in place the necessary measures to allow the Fed to fight the Great Recession as it should have, with negative interest rates. It is time for America’s economic policy-making apparatus to learn from its mistakes, on both counts.

Monetary Policy vs. Fiscal Policy: Expansionary Monetary Policy Does Not Raise the Budget Deficit> My view is that we need tools for macroeconomic stabilization that (a) can be applied technocratically and (b) do not add greatly to national debt when they are used to stimulate the economy. Monetary policy fills that bill, once it is unhobbled by eliminating the zero lower bound.

Get Real: Robert Shiller’s Nobel Should Help the World Improve Imperfect Financial Markets> For getting funds from those who want to save to those who need to borrow, the biggest wrench in the works of the financial system right now is that the government is soaking up most of the saving. The obvious part of this is budget deficits, which at least have the positive effect of providing stimulus for the economy in the short run. The less obvious part is that the US Federal Reserve is paying 0.25% to banks with accounts at the Fed and 0% on green pieces of paper when, after risk adjustment, many borrowers (who would start a business, build a factory, buy equipment, do R&D, pay for an education, or buy a house, car or washing machine) can only afford negative interest rates. (See “America’s huge mistake on monetary policy: How negative interest rates could have stopped the Great Recession in its tracks.”)

The solution to the dilemma of a Fed doing less than it thinks should be done because it is afraid of the tools it has left when short-term interest rates are zero? Give the Fed more tools. Unfortunately, it takes time to craft new tools for the Fed, but that is all the more reason to get started. (Sadly, even if all goes well in the next few years, this isn’t the last economic crisis we will ever have.) As I have written about here, here, and here, three careful and deliberate steps by the US government would make it possible for the Fed to cut interest rates as far below zero as necessary to keep the economy on course:

facilitate the development of new and better means of electronic payment and enhance the legal status of electronic money,

trim back the legal status of paper currency, and

give the Federal Reserve the authority to charge banks for storing money at the Fed and for depositing paper currency with the Fed.

If the Fed could cut interest rates below zero, it wouldn’t need QE, it wouldn’t need forward guidance, and it wouldn’t wind up begging Congress and the president to run budget deficits to stimulate the economy. And because the Fed understands interest rates—whether positive or negative—much, much better than it understands either QE or forward guidance, the Fed would finally know what it was doing again.

Automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans is so powerful that some economists will worry that its spread will help exacerbate a global glut of saving. But if paper currency policy gets out of the way of the appropriate interest rate adjustments, financial markets will find the appropriate equilibrium. They will balance the supply and demand for saving, and companies will realize the extent to which an abundance of saving makes available the funds they need to dream big by creating new markets and technologies that the future of America depends on.

Monetary policy does not act instantaneously. Even with excellent monetary policy, the economy may be away from the natural level for 9 to 15 months after an unexpected shock, simply do to the lags in the effects of monetary policy. But there is forewarning for many shocks, and shocks that act through the financial system are likely to have the same lags in their effects as monetary policy, so vigorous enough monetary countermeasures should be able to limit damage to a few month's time after a financial shock that does not diminish the long-run capacity of the economy. A key point though, is that "vigorous enough" may mean using negative interest rates for a brief period of time until the economy is put to rights and positive interest rates can be restored. On this, see my post "On the Great Recession." ...

... a track of prices that is too low is something that should be corrected just as quickly as a track of prices that is too high. If you don't think so, you probably have too high a long-run inflation target, as I discuss in "The Costs and Benefits of Repealing the Zero Lower Bound...and Then Lowering the Long-Run Inflation Target." With a zero inflation target, the idea that prices going off track in the downward direction is just as serious as prices going off track in the upward direction is easier to feel at a gut level.

When people save more, the whole economy benefits. A higher saving rate has the potential to reduce the trade deficit without protectionism. If accompanied by appropriate monetary policy, and not canceled out by bigger government budget deficits, a higher saving rate would also make more funds available for research and development. It should raise wages and reduce inequality.