Believe in Yourself

Link to the Youtube audio above

Link to the full lyrics of "A Rose is a Rose"

Very few of us, no matter how self-assured we may seem, escape periods of self-doubt. Mine came in the late 1990's. After much good fortune early in my career, around that time I had several National Science Foundation grant proposals rejected, one after another. One line of my thinking took me to resentment and anger at an economics profession that didn't appreciate the merit of my work. But another, insistent line of thinking took me to self doubt. In particular, I wondered if maybe I wasn't as good as I had thought I was. Maybe the anonymous reviewers who had rejected my proposals had it right in something they hadn't actually said outright, but seemed to be saying between the lines: maybe I was a mediocre economist. My brain looped over and over again between these two alternatives. Neither alternative was a pleasant one, but wondering if I was mediocre after all was the worst.

It might make a better story if I could say that I got out of this loop by myself, but I didn't. I had done some psychotherapy before, focusing in classic fashion on understanding my relationship with my Mother, and to a lesser extent, my Dad. Having felt some closure there, I had ended that round of therapy. Now I returned to therapy to figure out how to deal with these distressing career thoughts.

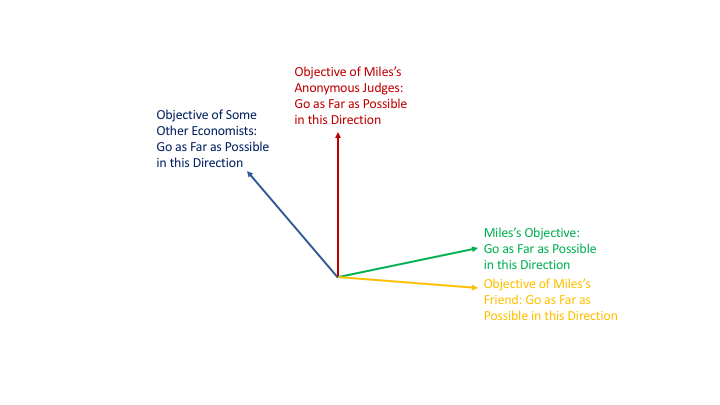

Very laboriously, and with much help, I did reach some degree of resolution. What brought me a degree of inner peace was an insight I have always pictured in terms of arrows representing the directions different economists want to go scientifically. Technically, these arrows are the gradient vectors of various people's objective functions for their scientific work.

I realized that I had been treating the anonymous judges of my National Science Foundation grant proposals as if they were God. And I had been assuming the standards by which they judged good work were the same as my own standards for good work. But in fact, their ideas of what constituted good work were very different from mine. What they thought an economist should be trying to do, was different than what I thought I should be trying to do. I really was trying hard to live up to my own scientific ideals, but my ideals were not the same as theirs. In a way beyond my fathoming, other economists had different values than I did. Some had scientific objectives close enough to mine that they felt I was largely going in the right direction. Others had scientific objectives far enough from mine they thought I was going in the wrong direction. The anonymous judges of my National Science Foundation grant thought I was going partly in the right direction, far enough to say a few positive words, but that I was also going off track in serious ways. No one thought I was doing nothing, though some thought a large share of my scientific activities were a waste.

I still think about these issues often. But instead of going back and forth between feeling unappreciated and doubting myself, now I go back and forth between thinking others should come more in my direction and thinking there are a wide variety of legitimate viewpoints, even if I find some of those viewpoints quite alien. That brain loop is not so bad even when I do get into it. And I find it easier to get out of that loop.

One thing that helps me now when I see others getting honors or rewards I wish I were getting is to remember what I have set as my own goals and think of how those goals are likely to be different than the goals of those who got those honors and rewards. (I think there are many other academics more subject to envy than I am, but I am very far from immune to envy!) It helps that I have some of those goals written down, most recently in the post I wrote for the 5th anniversary of this blog: "My Objective Function."

For me, one other thing that has helped me in times of envy and self doubt has been listening to the song in the Youtube audio at the top of this post: "A Rose is a Rose" from Susan Ashton's self-titled 1993 album "Susan Ashton." Let me give a commentary on the lyrics to point out how this song illustrates the principles above. These lyrics are by Wayne Kirkpatrick.

The song begins

You're at a stand still, you're at an impasse

Your mountains of dreams, seems harder to climb

By those who have made you feel like an outcast

Cause you dare to be different, so they're drawing a line

The words "you dare to be different, so they're drawing a line" are perfect for describing the difference in gradient vectors I have drawn above!

Next,

They say you're a fool, they feed you resistance

They tell you you'll never go very far

Notice that when the naysayers say "you'll never go very far," they are only counting your progress in their preferred direction. They aren't counting all the progress you are making toward what you think is important, but they don't.

The following two lines are some of my favorites. They operate on an emotional, fantasy level:

But they'll be the same ones that stand in the distance

Alone in the shadow of your shining star

It is not at all clear that such a moment of vindication will ever come, but just imagining it makes me feel better. People seldom admit they are wrong, and it is unwise to count on one's tormentors ever doing so. But what we can do is provide these moments of vindication for our friends and loved ones. One of the things my wife Gail and I do to keep our marriage strong is to say often to one another "You were right and I was wrong." You would be surprised at what a strong bond this creates, because you can't get that from just anyone!

Next, the refrain gives the key practical advice—don't overreact to criticism by changing your direction too much:

Just keep on the same road and keep on your toes

And just keep your heart steady as she goes

And let them call you what they will

It don't matter, a rose by any name is still a rose

It is worth thinking about criticism. It is worth making course corrections if you are genuinely convinced by something someone says. But unless you think there is some chance that what you have been doing is genuinely destructive, keeping on keeping on in mostly the same direction may be the course of action that is truest to your own values. (Of course, if you have been going contrary to your own values, you should rethink what you are doing and change course immediately.)

Next, the lyrics move to encouragement:

The kindness of strangers, it seems like a fable

But they've yet to see what I see in you

Friends are valuable advisors, both because they are more likely to share some of your sense of what is most important and because they know things about you and your life that others don't. It is important to distinguish between criticism or praise from enemies, criticism or praise from strangers, and criticism or praise from friends.

What I think is the heart of the lyrics are these two lines:

But you can make it if you are able

To believe in yourself the way I do

Notice that "believe in yourself the way I do" means "believe in yourself the way I, your friend, believe in you." It is hard to overstate the importance of believing in yourself. This is the theme of my post "The Unavoidability of Faith." Believing that by your efforts, you can make things better is the first step toward living a life that you love and saving the world.

After the second time through the refrain comes a reinforcement of the point that criticism does not change the facts of who you are. It may occasionally reveal something you hadn't realized before. But if you can view criticism with dispassion, it never makes you worse than you were before you heard the criticism:

'Cause a deal is a deal in the heart of the dream

And a spade is a spade, if you know what I mean

And a rose is a rose is a rose

Roland Benabou has a fascinating line of research (some of it with coauthors) in which people are modeled as trying to manipulate what information they have in order to feel better about themselves. I discussed these ideas in depth with Roland when the two of us went to dinner after a seminar I gave at the Economics Department at Princeton. I remember being both (a) being persuaded that this was a plausible account of how people actually behave and (b) thinking that such behavior is deeply irrational. More pointedly, I realized that (a) I do this and (b) even if there is any way that it could be a good idea for anyone to do this, it makes no sense at all for me to do it.

Born in 1960, I have already had many decades worth of evidence about my own characteristics. As long as I can avoid the kinds of extreme situation seen in movies, a single day's or a single week's worth of additional evidence about myself should not change that picture much. The biggest likely piece of information about myself would be to learn something that had been true for a long time that I had somehow managed not to see. That might sting, but at least I could console myself that others around me had probably seen that all along and some of them had stayed my friends anyway!

Even when it comes to criticism that I should really listen to in order to make a significant course correction in my life, I have learned the importance of what my therapist (a later one) called "titrating" the criticism: letting it in a little at a time, so I don't go down a psychological rabbit hole.

As for less helpful criticism, Wayne Kirkpatrick's lyrics say this:

To deal with the scoffers it's part of the bargain

They heckle from back rows and they bark at the moon

The goals and objectives that each person cultivates can be seen as a garden. Wayne's next line may or may not be true of your enemies' efforts:

Their flowers are fading in time's bitter garden

But ....

But if you believe in yourself and work hard, the next line—the last line before the final refrain—is true of your own garden:

... yours is only beginning to bloom