The Message of Mormonism for Atheists Who Want to Stay Atheists

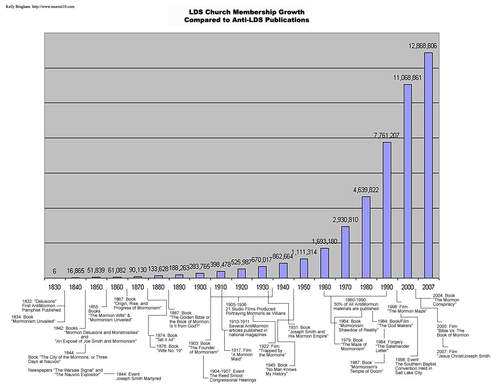

source (via googling “graph of Mormon membership”)

This post is a revised version of a sermon I gave to the Community Unitarian Universalists in Brighton, on May 20, 2012. They had asked me to try to give some insight into Mitt Romney and Mormonism. I thought it would be appropriate to post this near the first anniversary of the 2012 US Presidential election in which Mitt played one of the two starring roles. You can see the video of this talk here.

Here is the abstract for the sermon:

Even from the viewpoint of a thoroughgoing atheist or agnostic, Mormonism is a remarkable religion that has many lessons for those who wish to strengthen godless or agnostic religion. Its survival and growth and the generally high level of commitment of its members are due not only to strengths in its sociological structure and a theology that was fully modern and scientific at the time of its early 19th-century founding, but also to its ability to guide its members towards a distinctive type of mystical spiritual experience.

Today, by popular demand, I am going to tell you about Mormonism. My main qualification for telling you about Mormonism is that I was a staunch, active, observant, believing Mormon until I neared my 40th birthday, though I became more and more unorthodox toward the end of that time. Thus, I was a participant observer of Mormonism for a long time. Given that personal history, in the course of this sermon, I am sure I will slip into talking about Mormonism using the first person plural “we,” “us” and “our” and into referring to the Mormon Church as simply “The Church.”

Let me also mention several points of interest. My grandfather, Spencer Woolley Kimball was the 12th President and Prophet of the Mormon Church. He was a much-loved president and prophet, who extended the Mormon priesthood to blacks and was also president when the efforts of the Mormon Church provided the critical margin to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment. One of my great-great grandfathers was Heber C. Kimball, Brigham Young’s top counselor in Utah. Another one of my great-great grandfathers (whom I am named after) was Miles Park Romney, whose great grandson Mitt Romney is now almost certain to be the Republican nominee for President of the United States. Assuming he does, both Intrade and the Iowa Political Stock Market put his chances of becoming President of the United States at 40%.

In relation to Mitt Romney and Mormonism, let me say three things: one about the source of his ambition, one about why so many Mormons are Republicans and one about what we can learn about Mitt Romney from his service as a lay church leader. As a possible source of Mitt’s ambition to be president, let me say that Mormon men, and to a much lesser extent, Mormon women, are brought up to believe that they can change the world. When I was only about 8 years old, my mother arranged for me to sing in church a solo that had the refrain “I might be envied by a king, for I am a Mormon boy.” As teenagers, we were told that we were “a chosen generation, a royal priesthood.” Instead of hiding our lights under a bushel, we were exhorted to be an example to the world, and to prepare the world for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ by preaching “the Gospel”—which meant the Mormon gospel–in all the world. This was heady stuff. And then there was an unofficial, but intriguing prophecy that the Mormon elders would save the Constitution of the United States at a time when it was hanging by a thread.

In addition to being taught these things directly, there was another lesson in how much honor was given to Mormons who succeeded in the outside world, whether as a scientist like my great uncle Henry Eyring, as a golfer like Johnny Miller, or as entertainers, like Donny and Marie Osmond. I now view all of that as a sign of the status anxiety of a despised minority. Because of its history of polygamy and other weirdnesses, polls put American’s view of Mormonism about on the same footing as their view of Islam. So we were subtly urged to try to succeed in a big way to make Mormonism look better. So it would mean a lot to many Mormons to have Mitt Romney become president. And it would mean a lot to Mitt himself.

With lessons on Mormon Church history and their interest in genealogy in order to be able to baptize long-dead relatives, Mormons are aware of the history of persecution of Mormonism. In the 1830’s the Governor of Missouri issued an “Extermination Order” banishing Mormons from the state. In 1844, Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, was murdered by a mob. In 1857, the U.S. government sent an army to Utah to fight the Mormons. In 1890, the U.S. Government forced the Mormon Church to renounce polygamy by threatening to seize all of its property, including the Mormon temples. And to this day, Mormons deal in a mostly good-natured way with a lot of condescension and some overt hostility toward their religion.

Of course, it doesn’t always make friends to be claiming to have the “One True Church,” “The Only True and Living Church on the Face of the Earth.” The Mormon Church is not in communion with any other church. It does not recognize the baptism or any other rite of another church except for marriage according to the laws of the land, and even there does not recognize gay marriage as religiously valid.

Now let me tell you the story of why so many Mormons are Republicans. In the late 19th century, most Mormons were progressives in sympathy with the Democratic party. In the wake of narrowly averting having the Federal Government seize all the Mormon Church’s assets in 1890, having Utah be a territory made Mormons especially vulnerable to the Federal Government. So Church leaders were very eager to have Utah become a state, which would provide some protection. In 1896, Mormon Church leaders made a deal with the Republican party that if the Republican party would support statehood, then the church leaders would throw the church behind the Republican party. This is how they did it. Those church leaders who politically happened to be sincere Republicans were told to go out and speak their minds, while those church leaders who happened to be sincere Democrats were muzzled and told not to talk about politics at all. One Democratic-leaning apostle, Moses Thatcher, was dropped from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for refusing to be muzzled according to this plan. Because Mormon Republicanism grew out of the sincere beliefs and theological connections that the Republican half of the church leadership felt during that time when the Democratic half of the church leadership was silenced by church policy as part of the deal to get statehood, Mormon Republicanism has a theologically organic quality to it that wouldn’t have been there if the church had just told everyone directly that they were supposed to vote Republican. Progressive views might be theologically even more natural, but to most modern Mormons, they don’t seem that way, given the course that history has taken.

What does Mitt’s church service tell us about his beliefs? Wikipedia gives a good account of Mitt’s Church service. Using the metaphor of the Church as a tent with tent stakes, the Mormon Church calls a group of about ten congregations a “stake”—what the Catholic Church would call a diocese. Mitt served for eight years as the head of the Boston Stake—an unpaid 30-hour a week job in the Mormon Church on top of his job at Bain Capital. I spent seven years in the Boston Stake during college and graduate school, and can tell you that it is one of the most liberal stakes in the Mormon Church. In Wikipedia’s words, “Romney tried to balance the conservative dogma insisted upon by the church leadership in Utah with the desire of some Massachusetts members to have a more flexible application of doctrine.” As a result, for example, women had a somewhat greater role in the Boston Stake than in other areas in the Mormon Church. (My older brother served as the bishop over a congregation of older singles not long after Mitt stepped down as the Stake President of the Boston Stake. In accordance with that local Boston Stake culture, he was allowed to deal more flexibly with issues involving gays than would have been possible in most stakes in the Mormon Church.) Like ministers in other churches, as Stake President, Mitt spent a lot of time counseling people going through troubles of various kinds, including trying to solve problems among poor Southeast Asian converts. All of this was reflected in the relatively moderate political positions Mitt took in his campaign for Ted Kennedy’s senate seat and in his time as Governor of Massachusetts. Those who knew Mitt in the Church were not surprised by his positions then.

How then was Mitt psychologically able to turn around his positions so much in order to have a better chance in the race for the Republican presidential nomination? Remember that in his role as a Stake President, he needed to follow the directives of higher church leaders, and according to a common version of Mormon doctrine, even try to get himself to believe that what they were directing was for the best. (My father’s first cousin Henry B. Eyring, who is now the First Counselor to the President of the Mormon Church argued this view forcefully in a conversation I had with him a few days before he gave this sermon broadcast to Mormons around the world.) So the traditions of the Mormon hierarchy would have given Mitt practice in doing mental handstands to turn around his beliefs when necessary.

Enough of politics. I need a moral to the story. But before I draw a moral, let me give you three lists: things I carry with me from my Mormon background, things I miss that were there in Mormonism, and reasons why Mormonism is as successful as it is.

Things I Carry With Me. One thing I carry with me from my Mormon background is the emphasis on family and avoiding the excesses of workaholism. Mormon Prophet David O. McKay said it in a somewhat harsh way: “No other success can compensate for failure in the home.”

Second, I feel bad about idleness. When I was young, a Mormon hymn had this line, which was later expunged because of its harshness: “Only he who does something, is worthy to live; the world has no use for the drone.”

Third, I still don’t drink alcohol, never used tobacco, and even avoid the routine use of caffeinated coffee and other caffeinated beverages.

Things I Miss. One thing I miss about Mormonism is personally preaching and teaching religion. That is one reason I am here today. Nowadays, I may be one of the few proselyting Unitarian-Universalists.

Second, I miss the tight-knit Mormon congregations where everyone knows everyone else.

Third, I miss the sense of mission and grandeur of purpose in Mormonism. I am trying to replace that in my life. Mormonism instilled in me an ambition to change the world for the better that for a long time lacked direction due to my rejection of Mormonism.

source (via googling “graph of Mormon membership”)

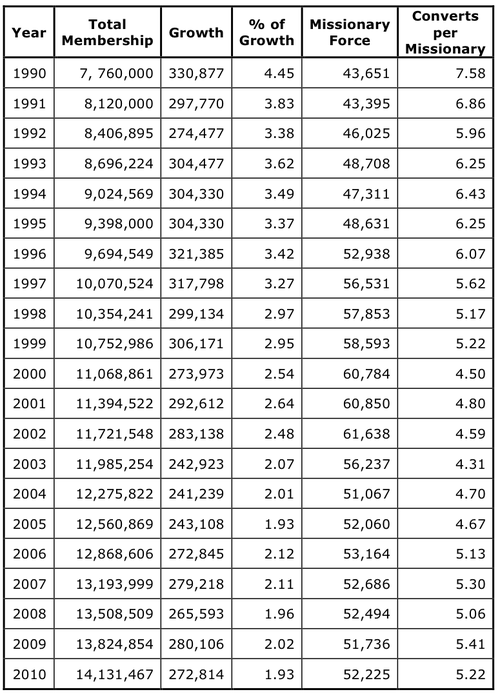

What Makes Mormonism as Successful as It Is? In the year 1830, there were quite a few Unitarians and Universalists but only six Mormons. Now there are officially 15 million Mormons in the world, about 5 million of whom regularly show up at church, while there are less than one million Unitarian-Universalists, maybe closer to half a million. The Sociologist Rodney Stark wrote a wonderful book called The Rise of Christianity that explains how the Early Christian church could grow so fast during the first few centuries A.D. by using Mormonism as a model of how fast growth can happen. Especially at the beginning, when a church starts out small, the key to growth is missionary effort. The Mormon Church has about 50,000 full-time proselyting missionaries in the field at any one time, who do a lot to generate more than a quarter of a million convert baptisms per year, where being baptized implies joining the Mormon church. These 50,000 missionaries serve unpaid. Often their families pay for their living expenses instead of the Mormon Church even providing subsistence.

source (via googling “graph of Mormon membership”)

How does the Mormon Church motivate this level of effort? To begin with, there is the expectation that all “worthy” young men go on two-year missions at the age of 18 or soon thereafter. (It used to be 19.) Note the gender-bias. Many young women go on missions, but they are not required to. Given the full weight of church doctrine behind every young man going on a mission, many young men are motivated by subjective spiritual experiences that convince them that “The Church is true.” This is called “getting a testimony.” Social pressure on the young man and social pressure on the parents to encourage the young man provide additional motivation. But there is yet another motivation. The young women are urged to have as their aspiration marrying a returned missionary. And indeed, to the extent that almost every worthy young man goes on a mission, not going on a mission becomes a sign of unworthiness in a variety of ways that genuinely would make someone less desirable as marriage material. For example, given the rules, premarital sexual activity or use of alcohol can prevent or delay a young Mormon man from going on a mission.

While on a mission, missionaries are urged to work even harder to “get a testimony”—subjective spiritual experiences that will convince them the Mormon Church is true. In addition, they are motivated to work hard by a system of promotions in rank no doubt devised by one of the many middle-aged businessmen who take three years off from a regular job to serve as a “Mission President”–the head of a group of 150 or so young missionaries in a particular region. Mormon missionaries always travel in twos, so they can keep each other from getting into trouble–and in other countries to make sure that one of them has been there long enough to be able to speak the language reasonably well. A missionary starts out as a junior companion. It is a big day when a missionary finally makes it to being a senior companion. Later on, the missionary can hope to be promoted to District leader over three to seven other missionaries, to a Zone leader over, say, nineteen, and maybe even to being an assistant to the Mission President. It is hard to communicate how much we as missionaries cared about those promotions. And of course, there could be demotions in the form of being exiled to a remote district where it was especially hard to make converts.

The Mission Presidents, who, as I mentioned, often have business experience, also devise many other motivational strategies akin to those in the world of sales. The goal and the measure of success is a relatively uncompromising goal: convert baptisms, with the convert understanding as fully as possible what a big commitment it is to join the Mormon Church.

After a mission, the Mormon man is supposed to get married relatively soon and the couple is supposed to start having kids soon after getting married. Contraception is OK, but having lots of kids is seen as a good thing. Elderly Mormons brag about the number of grandchildren and great grandchildren they have. So the Mormon Church grows faster by encouraging having a lot of kids as well as by encouraging young men to go on proselyting missions.

I left one key element out a minute ago. Mormons are supposed to get married in a Mormon temple “for time and all eternity” rather than getting married outside a temple “until death do us part.” Mormon temples are a central part of Mormonism’s strength. The secret ceremonies in Mormon temples have a certain grand sweep from reminders of the creation of the world to the ultimate destiny of those participating in those ceremonies. In the temple, Mormons make solemn promises, such as the promise to be willing to devote all of their time and resources to the Mormon Church if called upon and the promise to never have sex except within the bonds of marriage. Returning to the temple often to participate in ceremonies for dead relatives and other people already dead reminds Mormons of these promises they have made.

Mormon temples reinforce what I view as key theological strengths of Mormonism. First is the principle of Eternal Progression. The fifth President of the Mormon Church, Lorenzo Snow, expressed the doctrine most memorably:

As Man is, God once was; as God is, Man may become.

This is an absolutely central doctrine in Mormonism. I think the idea of perpetually improving and advancing–with no clear limits on what is possible–is a wonderful doctrine.

A second powerful doctrine is the doctrine that men and women are not created by God, but always existed in some form. The reason it is important is that it means that–although God will seem all-powerful in practical terms–God is not technically all powerful, and therefore it is more understandable why there is evil in the world when God is good. (This is an argument made by Sterling McMurrin in his classic The Theological Foundations of the Mormon Religion.)

Finally, Mormon theology draws strength from the fact that it is fully consistent with science as known at the time of its founder Joseph Smith’s death in 1844–including a surprisingly strong element of talking about other inhabited planets beyond the Earth. (This sympathy of Mormonism for the idea of other inhabited planets has made Utah a Mecca for science fiction writers.) I believe that, had he lived, Joseph Smith would have responded to Darwin’s discoveries by incorporating evolution into Mormon doctrine in a central way. But Joseph Smith’s successors, such as Brigham Young, were not as theologically creative. So Mormonism has some of the same tensions with evolution that many Christian churches display. The consistency of Mormon doctrine with at least early 19th Century science does a lot to help keep many highly educated Mormons in the Church. Another factor that helps keep many highly- educated Mormons from drifting away is the sheer intellectual interest of a complex doctrine, history and set of holy books. I found Mormon doctrine, history and scripture fascinating for many years.

Though I didn’t like the hierarchical aspects of Mormonism, the way the central leadership is structured is a sociological strength of the Mormon Church. Promising local leaders who have done a good job in unpaid leadership roles are promoted to central church leadership. Of those who become one of 15 apostles (12 in the “Quorum of the 12” and 3 in the “First Presidency”), the longest serving becomes President of the Church. Church leadership based on seniority—with some collective leadership elements—gives stability and continuity, and the wisdom of age, while the principle of continuing revelation permits any change to be made without loss of institutional legitimacy. Thus, the Mormon Church is able to be more flexible than the Catholic Church, which–as I understand it–must change by a process of interpretation rather than by any entirely new revelation.

Mormonism inculcates respect for authority. The church leaders repay that respect by trying to make Church members’ lives better within the limits of the perspective they have. Mormon church leaders are generally well-behaved in their personal conduct. In running the church, the only time I have seen high Church leaders behave in ways I consider morally objectionable (and this is much more emotional for me than that phrase conveys) has been when they were defending their collective authority and the stories underlying their legitimacy—and the legitimacy of the institution they have charge of.

The final strength of Mormonism that I want to highlight is its reliance on a lay ministry in relatively small congregations. Every Mormon who attends church is given a “calling” or an unpaid church job that involves him or her in helping to run the congregation. One of the biggest issues in the Mormon Church on the ground, on a week-to-week basis, is that the nature of the callings is not equal between men and women. But everyone is given some calling. And men who have leadership callings are made bishops and stake presidents on top of the regular jobs by which they make a living. Being involved in this way does a lot to generate commitment and loyalty. (This mechanism for deepening loyalty is especially important among well-educated Mormons.)

My younger brother’s father-in-law Eugene England was a well-known liberal Mormon writer who felt that the fact that Mormons are assigned to a Mormon congregation based on geography rather than choosing which Mormon congregation to go to does a lot to help make sure that Mormons rub shoulders with Mormons in different social classes. (Here is a link to the essay where he makes that case.) Certainly, for the men who take turns being a bishop in charge of a congregation for a few years, counseling people who are suffering or in trouble is an eye-opener. And in a smaller way each Mormon adult who shows up at Church is assigned with a partner to look after several Mormon families with monthly visits.

Lessons for Unitarian-Universalism and Other Agnostic Religions. It is time to draw the moral or lesson of the story, as I see it. The first lesson I draw is that proselyting works. I believe we should make more efforts to share Unitarian-Universalism. We have something good here, and we should give people a chance to look it over. Let’s spread the word that there is in the world a living, breathing, agnostic religion with full freedom of thought and belief. Most people don’t know that. They think that all religions require a specific belief in the supernatural.

The second lesson is that a religion can be strengthened by involving all its members directly in the work of the religion in one way or another. Especially at the local level, it can work well to blur the line between what the paid minister does and what the members of the congregation do.

The third lesson, drawn from the way that Mormon missionaries are motivated, is to always remember the power of nonfinancial motivations for people. Up to a point, what we honor people for doing, and dishonor them for not doing, gets done. (This is a theme of my posts “Scott Adams’s Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich,” and “Copyright.”) Of course, there is a tradeoff between accepting people for who they are and disapproving of things that really are bad behavior. And we need to make sure we are disapproving of genuinely bad behavior rather than just going with our prejudices.

The fourth lesson is the importance of a sense of purpose and the belief that we can make the world a better place. (See my post “So You Want to Save the World.”)

The final lesson is the importance of having powerful theologies of human advancement. What is a theology? A theology is a story of how the world works, focusing on the very most important questions, plus a vivid picture of a big objective, such as heaven, a loving community, or justice. (See my post “Teleotheism and the Purpose of Life.”)

In some of the Landmark Education personal growth courses I once took, we were asked to speak what they called a “possibility”—an attractive vision of where we wanted things to go. Mine was “the possibility of all people being joined together in discovery and wonder.” Others in the course painted other wonderful pictures of possibilities with a short phrase. Our Unitarian-Universalist congregations are a place where, in addition to taking care of our own souls, we get together to talk about our individual visions of something good for humanity and to organize subgroups to work toward these various goals. (See my post “UU Visions.”)

In choosing our goals and visions for humanity, we sometimes take our clue from politics, but given the state of politics, I hope that we do not always take our clue from existing political ideals. There is a limit to what tactical politics can achieve. Sometimes we need to imagine something totally new, beyond preexisting political categories, as I believe the framers of the U.S. constitution did in 1787, and as the Suffragettes at Seneca Falls did in 1848, pushing for women to have the right to vote.

I believe that religion, and especially free-thinking religion, should play a part in bring forward new visions for the advancement of our Republic and for the advancement of Humanity.

Note: If you enjoyed this post, you may enjoy some of these in addition to the posts flagged above: