John Locke Off Base with His Assumption That There Was Plenty of Land at the Time of Acquisition

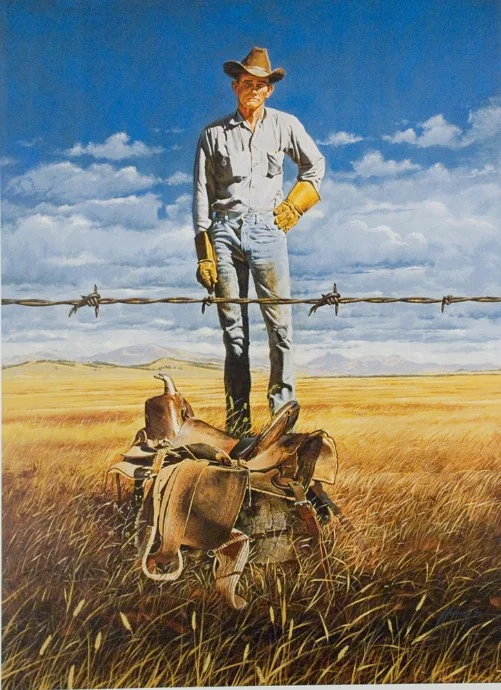

"Range's End" by Edward Hopper (or is it "Ranges End"?)

In "John Locke's Song of Praise for Work," treating section 32 of John Locke's 2d Treatise on Government, I discuss John Quiggin's post "John Locke Against Freedom." John Quiggin argues that John Locke wrote his 2d Treatise in order to justify English freedom on the one hand, enslavement of Africans and expropriation of Native American lands on the other. I am not willing to follow John Locke in disregarding the claims of Native Americans. (See "John Locke on Diminishing Marginal Utility as a Limit to Legitimately Claiming Works of Nature as Property" where I argue against the expropriation of native lands as follows:

To justify, theoretically, taking that land from the Native Americans, one would have to add the principle that when technology changes so that people need less land to support themselves, then previous land claims need to be reevaluated. In general, such a principle is a recipe for a big mess. Better to, at a minimum, require rich outsiders to purchase land as European Americans did from Native Americans in a few cases, and as the European New Zealanders did to a much greater degree from the Maori. If technology has really improved dramatically, they should be able to do so.

But even if one blithely and callously disregards the claims of Native Americans to the lands they occupied before the Europeans arrived, John Lockes' argument in section 33 that there is so much land that no one should object to someone claiming the amount that individual can cultivate runs afoul of actual history after the time John Locke wrote. When farmers claimed land in the American West, and put up barbed wire to mark their claim, the cowboys who had been used to driving cattle through were mightily aggrieved. Keep that vivid bit of history in mind when reading the text of section 33:

Nor was this appropriation of any parcel of land, by improving it, any prejudice to any other man, since there was still enough, and as good left; and more than the yet unprovided could use. So that, in effect, there was never the less left for others because of his inclosure for himself: for he that leaves as much as another can make use of, does as good as take nothing at all. No body could think himself injured by the drinking of another man, though he took a good draught, who had a whole river of the same water left him to quench his thirst: and the case of land and water, where there is enough of both, is perfectly the same.

Of course, tortured logic is exactly what one should expect when someone is twisting his arguments to get a complex set of politically desired argumentative results that don't really hang together.

If John Locke's theory of land ownership is marred, where then can one turn for a theory of land ownership? Here is my view so far:

- As John Quiggin quotes David Hume, but limited to land only: “there is no property in ... lands ... when carefully examined in passing from hand to hand, but must, in some period, have been founded on fraud and injustice.” (The original of the quotation from David Hume mentions houses as well, but I don't agree with David Hume about houses, since someone might have built their own house or built a house and voluntarily conveyed it to someone else.)

- As with national borders, to avoid endless conflict, there must be a statute of limitations on land claims.

- There should be a heavy Henry George tax on land, to reduce the injustice from the current distribution of land based on the first two points. (I won't call it a single tax, because unfortunately, it would be hard to raise enough revenue from this alone to do all of the things the government is currently doing.) Zera has a nice post on the "Economic Theories" blog about John Stuart Mill's approach to such a land tax.

What seems to me even more precious than land is sovereignty: the right to construct one's own government, which in our world—both now and historically—often goes along with certain pieces of land. John Locke, although he deserves to be reprobated for his support of slavery and the expropriation of Native American lands, does deserve credit for helping to at least some degree separate the justification of sovereignty from the possession of particular pieces of land.

Don't miss other John Locke posts. Links at "John Locke's State of Nature and State of War."