Freedom Under Law Means All Are Subject to the Same Laws

What does it mean to be free? If it means to have no legal restraints at all, then only one person at the apex of society can be free. If, instead, "freedom under law" is possible, it means to have the maximum amount of freedom that anyone in society has. That is, one can think of "freedom under law" as like a "most-favored-nation" clause: "freedom under law" is facing only the restrictions on one's behavior that everyone faces.

Interestingly, this definition "freedom under law" works for both "freedom under natural law" and "freedom under civil law." Here is John Locke's explanation of freedom under law in section 22 of his 2d Treatise on Government: “On Civil Government” (in Chapter IV "Of Slavery"):

THE natural liberty of man is to be free from any superior power on earth, and not to be under the will or legislative authority of man, but to have only the law of nature for his rule. The liberty of man, in society, is to be under no other legislative power, but that established, by consent, in the commonwealth; nor under the dominion of any will, or restraint of any law, but what that legislative shall enact, according to the trust put in it. Freedom then is not what Sir Robert Filmer tells us, Observations, A. 55. “a liberty for every one to do what he lists, to live as he pleases, and not to be tied by any laws:” but freedom of men under government is, to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society, and made by the legislative power erected in it; a liberty to follow my own will in all things, where the rule prescribes not; and not to be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, arbitrary will of another man: as freedom of nature is, to be under no other restraint but the law of nature.

For freedom under civil law, the key clause is Robert Filmer's: "to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society ...". This idea of everyone being subjected to the same laws was taken seriously in late 19th century, early 20th century US constitutional law as the prohibition against "class legislation." A prohibition against "class legislation" has the potential to put a barrier in the way of special interests lobbying for laws that will inhibit competitors.

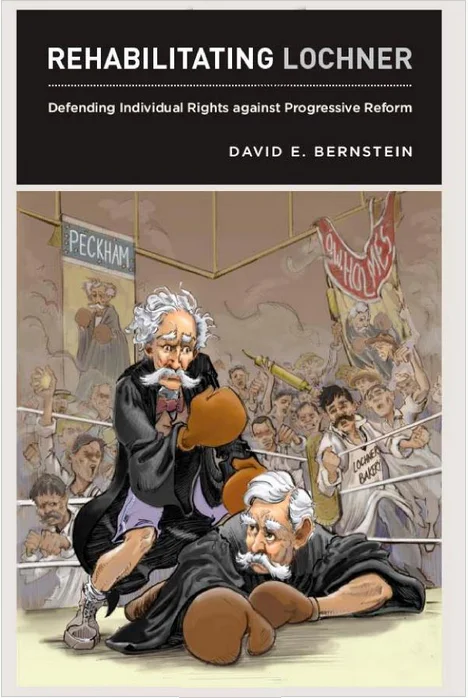

Among US Supreme Court decisions, Lochner v. New York is one of the most famous, and one of the most criticized. Going into why would take this post too far afield, but I want to quote the discussion of "class legislation" in David Bernstein's book "Rehabilitating Lochner." The principle against class legislation came up in that litigation because the limitation on bakers' hours at the heart of the case was in important measure an attempt to benefit other bakers by disadvantaging newly immigrant bakers. Here is David:

The liberty of contract doctrine arose from two ideas prominent in late-nineteenth-century jurisprudence. First, courts stated that so-called "class legislation"-legislation that arbitrarily singled out a particular class for unfavorable treatment or regulation-was unconstitutional. Courts used both the Due Process and the Equal Protection clauses as textual hooks for reviewing class legislation claims. Indeed, the opinions were often unclear as to whether the operative constitutional provision was due process, equal protection, both, or neither. Second, courts used the Due Process Clause to enforce natural rights against the states. Judicially enforceable natural rights were not defined by reference to abstract philosophic constructs. Rather, they were the rights that history had shown were crucial to the development of Anglo-American liberty.

CLASS LEGISLATION ANALYSIS AND THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE

Opposition to class legislation had deep roots in pre-Civil War American thought. After the Civil War and through the end of the Gilded Age, leading jurists believed that the ban on class legislation was the crux of the Fourteenth Amendment, including both the Equal Protection and Due Process clauses. Justice Stephen Field wrote in 1883 that the Fourteenth Amendment was "designed to prevent all discriminating legislation for the benefit of some to the disparagement of others." Each American, Field continued, had the right to "pursue his [or her] happiness unrestrained, except by just, equal, and impartial laws." Justice Joseph Bradley, writing for the Court the same year, declared that "what is called class legislation" is "obnoxious to the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment." In Dent v. West Virginia, the Court even declared that no equal protection or due process claim could succeed absent an arbitrary classification.--' Influential dictum from Leeper v. Texas suggested that the Fourteenth Amendment's due process guarantee is secured "by laws operating on all alike."

The Supreme Court, however, interpreted the prohibition on class legislation quite narrowly. In 1884 it unanimously rejected a challenge to a San Francisco ordinance that prohibited night work only in laundries.-' Justice Field explained that the law seemed like a reasonable fire prevention measure, and that it applied equally to all laundries. The following year, a Chinese plaintiff challenged the same laundry ordinance, alleging that its purpose was to force Chinese-owned laundries out of business. Field, writing again for a unanimous Court, announced that-consistent with centuries of Anglo-American judicial tradition and prior Supreme Court cases-the Court would not "inquire into the motives of the legislators in passing [legislation], except as they may be disclosed on the face of the acts, or inferable from their operation. ..."' The Court's refusal to consider legislative motive severely limited its ability to police class legislation.

To my mind, the unwillingness to inquire into the motives of the legislators was a mistake. Looking for the motive to help one group even at the expense of another seems one of the easiest common-sense ways to figure out if something is class legislation. Nowadays, we recognize laws that are designed with the motive of disadvantaging African Americans as unconstitutional. This is that same principle applied to many classes of people. And even if the prohibition against class legislation were limited to a prohibition on legislation that would disadvantage the poorest of the poor, in line with John Rawls's recommendations in A Theory of Justice, it would be an extremely valuable principle. (For more thoughts on that score, see "Inequality Is About the Poor, Not About the Rich.")

Though defining "equality before the law" in particular cases is difficult, it seems to me that one way or another in all countries that believe in freedom and the rule of law, these ideas have a proper role in constitutional law:

"to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society"

"the right to 'pursue his [or her] happiness unrestrained, except by just, equal, and impartial laws'"

"laws operating on all alike"

Addendum, August 4, 2019: As John L. Davidson points out, in general, inquiring into legislators’ motives is unworkable. The only time I think legislators’ motives should come into play in jurisprudence is when legislators’ motives were to do something constitutionally impermissible.

For links to John Locke posts on the previous 3 chapters of the 2d Treatise, see "John Locke's State of Nature and State of War."