Today is the 6th anniversary of this blog, "Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal." My first post, "What is a Supply-Side Liberal?" appeared on May 28, 2012. I have written an anniversary post every year since then:

- A Year in the Life of a Supply-Side Liberal

- Three Revolutions

- Beacons

- Why I Blog

- My Objective Function

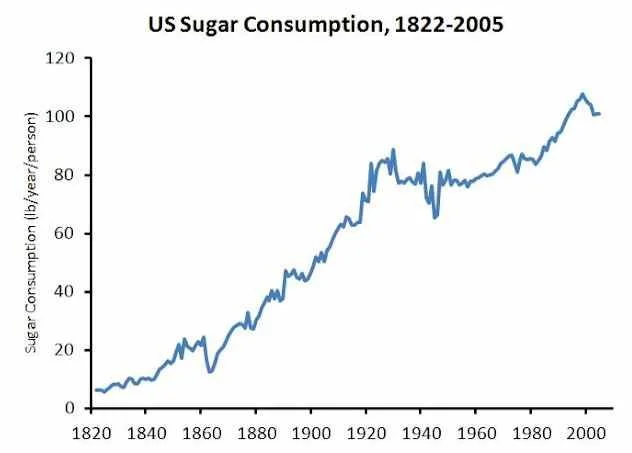

I asked my self the question "What distinguished my blogging this past year from previous years?" The answer was obvious: for the first time, in the past 12 months, I have written a lot about diet and health. You can see links to those posts at the bottom of this post. My first major post on diet and health was "Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon," on September 21, 2017. That was preceded by

My posts on diet and health have attracted a lot of readers. For all of 2017, three of the top four posts talk about diet and health. Here is the top of the list from "2017's Most Popular Posts":

- Five Books That Have Changed My Life 6936

- Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon 5979

- There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale 4441

- Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid 3927

(I discussed Jason Fung's book The Obesity Coden as one of the "Five Books That Have Changed My Life.")

In early July, I'll do a data post on the most popular posts in the first half of 2018. I can tell you already that diet and health posts will be at the top—both in the category of new posts in 2018 and posts from earlier years with continuing popularity. (Let me hasten to add that diet and health posts only account for about one blog post per week. I am still writing all the time about everything else!)

Because blogging about diet and health has become a thing for me, I thought I should give a little more history about why I am interested in this area. Part of the answer is that, as I intimated in "On Teaching and Learning Macroeconomics," as a macroeconomist I am always on the lookout for things that are a big deal for overall social welfare. You can see that angle on the rise of obesity in "Restoring American Growth: The Video."

Joe Weisenthal asked me how I got interested in this area in the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." I said two things. First, I have very broad interests. In my recruiting conversations here at the University of Colorado Boulder, I legitimately claim to have a toe in almost as many fields of economics as I have toes. I am also proud to say that according to REPEC I am currently in the top 100 economists in the world in "breadth of citations across fields." The second reason I gave Joe for how I got into diet and health is that it is personal for me.

Today, let me explain why my life experiences have made me think about diet and health. I am calling this a barycentric autobiography. "Bary" means heavy in Greek, and shows up in the the weight-loss context in the word "bariatric surgery." The word "barycentric" normally refers to the center of mass or weight, as in barycentric coordinate systems which specify a location by the weights it would take to make that location a center of mass. But here I am using the word "barycentric" in "barycentric autobiography" half in jest to mean "centered on weight."

My story begins with the fact that my mother was quite overweight. As I hinted at in my eulogy "My Mother," my mother had strong views about many things. She told us, her children, that from her we probably had gotten the "fat gene" and so needed to be especially careful about what we ate. She gave us strict rules that we couldn't eat at home outside of meal times without special permission. I remember being amazed when I visited my friend David Benforado's house how confident he was that his parents would be OK with his getting us ice cream for a snack when they weren't around. When I was turning 8 years old, the age when Mormons get baptized "for the remission of sins," I remember thinking I would have to stop stealing raisins from the refrigerator once I was baptized.

My Dad was always relatively thin. My mother would have said he just didn't have the fat gene. (Recently, human genetics research has shown convincingly that there isn't one gene that has a big effect on body mass index; rather there are many, many genes that each have a small effect on body mass index, adding up to a big effect of genes overall, but one that leaves plenty of room for other factors besides genes to have an effect.) But there was another unusual fact about my Dad's eating habits that I now think helped keep him thin: my Dad routinely skipped breakfast and lunch. Typically, he only ate in the evening. Then he ate whatever he wanted. (See "Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts.")

The upshot is that I was very aware of the dangers of weight gain from an early age. But my knowledge of what might contribute to weight gain was only what was conventional wisdom at the time. I was born in 1960. One idea common in the 70's, during my teens, was the idea that foods helpful for diabetics were also likely to be helpful for losing weight or avoiding weight gain, and avoiding sugar was thought to be crucial for diabetics.

Another bit of conventional wisdom both then and now is that exercise is helpful in avoiding weight gain. My take on the scientific evidence circa 2018 is that the idea exercise is helpful in avoiding weight gain is true, but that regular exercise is much more helpful in avoiding weight gain that it is in inducing weight loss. (See the article I renamed "Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies.") Importantly, other evidence suggests that exercise helps make people happy, smart and healthy even when it does not lead to weight loss. In my late teens and early twenties, I would jog regularly. Later on, I made it a practice, still to this day to do a walk almost every day. I also have been on the lookout for situations where a willingness to do some serious walking and count it as part of my exercise time could save me parking fees or other inconveniences. And I have taken to heart the idea that one should lean toward taking the stairs instead of the elevator whenever it's reasonable.

The guidance of the conventional wisdom was not enough to keep me from gradually gaining weight over the decades. I am 5' 7.5" (171.5 centimeters) tall. In high school, I wrestled at the weight of 132 pounds. When I married Gail in 1984, I weighed 148 pounds. By the time I moved from the University of Michigan to the University of Colorado Boulder in 2016, I weighed around 188 pounds. Along the way, I regularly read popular press articles about diet and health. In the late 1980's I followed the prevailing lowfat advice at the time. I ate a lot of Bran Flakes and skim milk and gained quite a few pounds from that experiment. Every once in a while I would go off ice cream and would lose several pounds. But I was mostly grateful I didn't have worse problems with weight, since I saw many friends who had weight problems, several of whom had to be treated for sleep apnea (trouble in breathing at night), for which the key risk factors are getting older and being overweight.

In the Summer of 2016, we sold our house in Ann Arbor before we could move into our new house in Colorado, so we stayed in an Airbnb in Ann Arbor for a couple of weeks at the tail end of living in Michigan. During that time, I ran into one of my friends in at the University of Michigan Survey Research Center who said he had had a lot of success losing weight on a program where he would alternate between days when he would eat freely and days when he would eat only 500 calories. He was convincing enough that I decided to try it. I followed that approach for about 6 months—roughly the second half of 2016—though I think I targeted 600-650 calories on the low-food days instead of 500. Trying to figure out how to get full on only 600 or so calories on the low-food days drove me to invent for myself the big salads that are still a mainstay of what I eat.

I did lose some weight and found the program of eating only 600 or so calories every other day tolerable. But my wife Gail characterized me as grumpy on the days I was eating only 600 or so calories. I certainly felt a bit deprived. Once we were in Colorado, the days of unrestricted eating often featured a trip to one of the Boulder area's Sweet Cow ice-cream shops.

Toward the end of 2016, I read reviews of Gary Taubes's book The Case Against Sugar. My wife Gail and I read it soon after it came out in December 2016. Online, Gail ran into someone who said that if you liked The Case Against Sugar, you should read Jason Fung's book The Obesity Code. We read that as well. Of the two books, The Obesity Code is much more impressive in how careful its arguments are. But both books had an effect on us. Gail and I went off sugar, bread, potatoes and rice in early 2016, and a few months later began experimenting with the periods of no food—"fasting"—that Jason Fung recommends. I'll leave the rest of Gail's story for her to tell. But my experience was that the pounds came off relatively quickly. Now, in May 2018, I weigh about 155 pounds. My goal for the next six months is to stay about even.

One thing that gave me the confidence that I could fast is that as a Mormon (up until the age of 40) I fasted for close to 24 hours once a month. But relative to that experience fasting as a Mormon, I found fasting remarkably easy when I began fasting after having been off sugar, bread, potatoes and rice for a couple of months. The other remarkable comparison was that not eating at all for a whole day was a lot easier and more pleasant than eating 600 calories had been when I had been on the program alternating between days of 600 calories for the day and days of totally unrestricted eating. I attribute the difference to what was happening to my insulin levels; you can see how I think about this theoretically in "Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon" and "A Conversation with David Brazel on Obesity Research."

In brief, the idea is fasting can get one's insulin level low enough that body fat begins to be metabolized. Once body fat begins to be metabolized, there are enough nutrients in the bloodstream that hunger is quite mild. In other words, effective weight loss keeps you from being very hungry because your cells are getting fed well from your own stores of body fat. If you are really hungry, that is a sign not much fat burning is taking place. (According to my current views, the key to getting your body to metabolize body fat is to get your insulin levels low. The two keys to doing that are fasting and eating low on the insulin index when you do eat, as I discuss in "Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.")

In Spring 2017, I gave my inaugural lecture for the Eugene D. Eaton Jr. Chair I hold here at the University of Colorado Boulder. You can see it in "Restoring American Growth: The Video." I realized that some of the feeling that the pace of improvement had slowed down in the United States had to do with something not measured in GDP: the rise of obesity. In that talk, I shared some graphs showing how widespread and relentless the rise in obesity is. This, along with all the interesting things I was learning from my own experience with a roughly lowcarb diet and fasting made me think I should start blogging about diet and health.

The rest of the story is all there in my posts on diet and health. I plan to keep reading about diet and health and giving my views on what I read. And I plan to keep sharing practical approaches that worked well for me. I appreciate all the interest people have shown in what I have written about diet and health, and people who have shared the results from their own experience in trying out some of the ideas I have been talking about.

Stepping back for a second from diet and health in particular, in my six years of blogging, I have been very grateful to have readers who have been willing to accept the wide range of topics I write about. Early on, I made the decision that I was going to write about politics and religion in addition to economics. And I have touched on many other topics along the way. To me, all of it is about trying to make the world a better place.

Turning back the rise of obesity would definitely make the world a better place. Getting the science right is crucial for that. Let me say in the strongest terms: I don't think the current conventional wisdom on obesity has the science right. What those who are now called experts say cannot be fully trusted. In my view, we as a society dare not trust an important scientific question to a single discipline. Each discipline gets blind spots. So we need to have at least two disciplines studying each important scientific question. For obesity research, I think economists have the right training to be immensely helpful in cross-checking the views of those who are now treated as experts in nutrition and weight loss.

For me personally, diet and health is only going to be a modest fraction of what I am working on in my career, but I hope some economists make it a major part of their careers. And let me say with all righteous indignation, in advance: Anyone who discourages an economist inclined to pursue research questions about diet and health deserves a black mark in history. Economists working on questions of diet and health have the power to literally save thousands and thousands of lives. I hope to live to see the day when many economists pursue such research.

Don't miss these other posts on diet and health and on fighting obesity:

Also see the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation."