Joe Henrich on Differences in Human psychology and Functioning around the Globe

Here are two links to particular discussions on Joe’s very interesting Twitter feed:

Joe Henrich is someone I knew well at Michigan. I predicted his stellar career before certain others.

One Nation

The beginning of the 2020 US presidential campaign is a reminder of the divisions within the United States. Understanding those with different views is not only the road to healing those divisions, but also, for either side, the road to winning in the general election sixteen months from now. Most of you and I already have a reasonably good understanding of the “Progressive” viewpoint that is now so influential in the Democratic Party. Therefore, let’s try to dig into the views of those who are enthusiastic Trump supporters as well as those who might reluctantly vote for Donald Trump because they are uncomfortable with the Democratic Party alternative.

Peggy Noonan, in her most recent op-ed “The 2020 Democrats Lack Hindsight,” emphasizes “identity” issues as important to those who enthusiastically support Donald or might vote for him because of discomfort with the alternative. She quotes a middle-aged Kansan man, who said:

Every day, Americans are told of the endless ways they are falling short. If we don’t show the ‘proper’ level of understanding according to a talking head, then we are surely racist. If we don’t embrace every sanitized PC talking point, then we must be heartless. If we have the audacity to speak our mind, then we are most definitely a bigot. …

We are jabbed like a boxer with no gloves on to defend us. And we are fed up. We are tired of being told we aren’t good enough. … in Donald Trump, voters found a massive sledgehammer that pulverizes the ridiculous notion that Americans aren’t good enough.

The previous week, in “My Sister, My Uncle and Trump,” Peggy quoted her sister and uncle and characterized these two early Donald supporters this way:

They were patriots; they loved America. They weren’t radical; they’d voted for Republicans and Democrats. They had no grudge against any group or class. They knew that on America’s list of allowable bigotries they themselves—middle Americans, Christians who believed in the old constitutional rights—were the only ones you were allowed to look down on. It’s no fun looking down on yourself, so looking down wasn’t their habit.

A good resolution of cultural issues and racial, ethnic and gender disparities could help heal the divisions in America. (Here, I will leave aside the fraught issue of abortion. For my views on abortion, see “Safe, Legal, Rare and Early.”) Let me give my opinion on a way forward.

First, for racial, ethnic and gender disparities, as in the area of climate change, a crucial rule to make a civil discussion possible is that recognition of a serious problem should not be construed as agreeing that the remedy urged by those highlighting the problem is the right remedy. People need to have confidence that their views about a remedy will be respected enough that they are not giving away the game by acknowledging the reality of a problem. Admitting a problem exists should not be construed as agreeing to be railroaded into a particular remedy.

As Peggy Noonan points out, people hate being called racist or sexist or otherwise being told they are deplorables. It is good to look for alternative explanations for people’s attitudes before jumping to accusing people of invidious racism or sexism. Here I use the phrase “invidious racism or sexism” to mean seriously blameworthy racism or sexism as opposed to the even more troublesome racist and sexist attitudes that are like the air we breathe and hence not particularly blameworthy in an individual. Non-invidious pervasive racism or sexism is one of the most important alternatives to positing invidious racism or sexism.

Second, racism and sexism can often be supported by systemic structures plus routine self-interest and self-aggrandizement. For example, in economics departments, professors have a strong interest in building up their own fields and their own styles of economics. To the extent their numbers tilt male right now, and male economics professors have, on average, different field and style preferences, their desires to build up their own fields and styles of economics will handicap female job candidates, even if they don’t have any prejudice at all against women who happen to be doing the field and style of economics they are looking for.

Turning to invidious racism and sexism, it is important to realize that some comes from personal grievances that might not have happened in a better society. For example, children often live in fear of being bullied. Two types of bullying and nasty teasing can lead to invidious racism, sexism and other bad attitudes. First, if the bully happens to be of a different race, the hatred of that bully might be overgeneralized into a hatred of a race. Second, bullies often taunt other children by saying they are a member of disfavored group. When I was a boy, bullies often taunted other boys by saying they were a “fag,” which powerfully got across the idea that to be a homosexual was bad. Both of these mechanisms for creating invidious racism, sexism and other bad attitudes can be forestalled by reducing the amount of bullying that children face from one another. (See my post “Against Bullying.”)

Another reduceable source of invidious racism is the centrality to our current society of prizes—such as admission to elite colleges or professional schools or prestigious jobs—that have an excessive amount of surplus. If elite colleges and professional schools each expanded the number of students admitted, it would reduce the stress on those trying to get admitted and reduce the likelihood that that stress would lead to resentment of affirmative action—and might even reduce the sense that affirmative action was needed, because admission wasn’t quite such a big prize.

When particular jobs have a huge amount of surplus for those who get them, it would be helpful for us to reduce the gap in prestige, pay and perks between them and the next job down on the ladder. The top nurses on the totem pole should be at about as high on the ladder as the least of even experienced doctors. The most talented non-tenure-track lecturers should have at least as much prestige as struggling professors. And the most skilled paralegals should be nearly the equal in prestige to mediocre members of the bar.

Eliminating the kinds of gaps beloved of those doing regression discontinuity analyses—in this case between those barely admitted and barely rejected, or between those barely hired and those barely turned away—should reduce any resentment due to affirmative action, but will still leave the kind of racial/ethnic animosities common against Jews and Asian Americans. There is no single solution to all forms of racism or ethnic or religious hatred.

Finally, there are likely to be many interventions that can be made with schoolchildren that can reduce racism, sexism and other bad attitudes. The key thing is to have these programs evaluated in randomized trials. Just because someone believes something will help doesn’t make it so. (For older age groups, some evidence has come in suggesting that sensitivity training of the common types is not very effective.) There is no shortage of ideas to be tested. In “Nationalists vs. Cosmopolitans: Social Scientists Need to Learn from Their Brexit Blunder” I write:

As a Cosmopolitan, what I most want to know from social science is what interventions can help make people more accepting of foreigners. Somewhat controversially, it is now common in the US for elementary school teachers to make efforts to instill pro-environmental attitudes in schoolchildren. Whether or not those efforts make a difference to children’s attitudes, are there interventions or lessons that can make schoolchildren and the adults they grow up to be likely to feel more positive about the foreign-born in their midst? For example, having had a very good experience learning foreign languages on my commute by listening to Pimsleur CDs in my car, I wonder whether dramatically more effective Spanish language instruction for school children following those principles of audio- and recall-based learning with repetition at carefully graded intervals might make a difference in attitudes toward Hispanic culture and toward Hispanics themselves in the US.

Although it is the province of social scientists to test interventions intended to improve attitudes toward the foreign-born, many of the best interventions will be created by writers, artists, script-writers, directors, and others in the humanities. There are also many other marginalized groups in society, but the strength of anti-foreigner attitudes suggests the need for imaginative entertainment and cultural events to help people identify with human beings who were born in other countries.

My bottom line is that when we think of racism and sexism and other bad attitudes, we should consider root causes that are not entirely within the individual and not leap too quickly to castigating individuals. And we should cast the net wide for root causes and plausibly helpful interventions, and test hypotheses rigorously. Some proposed remedies for racism, sexism and other bad attitudes may do more harm than good. It does not make one a racist, sexist or bad person to say that we should ask for evidence about the effects of various remedies. (And we should gather evidence for the effects of remedies recommended by those on the right as well as by those on the left. For example, effective crime control measures that make people feel safer might reduce racism, or certain kinds of easy cultural training that immigrants are happy to receive might make them seem less threatening to the native-born.)

In the last few years I have become aware of the serious possibility that for a long time we were successful at driving racism and sexism underground by silencing people with such attitudes, without fully convincing people to relinquish such attitudes. Silencing people with such attitudes may reduce the chance of transmitting those attitudes to the rising generation, but it also causes the resentment people almost always feel when they can’t say their piece. If, as a society, we had not succumbed to the temptation o trying to silence people, we might—after great effort—now be further along the road to persuasion. Letting people say their piece often seems threatening when we disagree strongly (and perhaps especially when we disagree strongly for good and sound reasons), but I believe letting people say their piece and then responding with our views is the wiser course.

A good rule of thumb is to avoid reading anyone out of the human race—not even those who would read others out of the human race. Given our evolutionary heritage, taking an “Us and Them” approach is extremely contagious. Let’s not play with that kind of fire. In a cultural war like the one we are in now, I believe it is the side that can best rise above the us-versus-them temptation that will prevail.

Related posts and links, beginning with those flagged above:

Patrick Sharkey Questions the Lead Poisoning—>Crime Hypothesis →

Hat tip to Noah Smith.

Jonathan Shaw: Could Inflammation Be the Cause of Myriad Chronic Diseases?

Inflammation plays a role in many diseases, according to Jonathan Shaw’s fascinating Harvard Magazine article shown above: “Raw and Red-Hot: Could inflammation be the cause of myriad chronic conditions?” I found three points Jonathan made especially interesting.

First, arterial plaques that block blood flow in a way that can cause heart attacks or strokes may owe just as much to inflammation as they do to cholesterol. For example, one of the most powerful predictors of cardiovascular health is C-reactive protein, which is related to inflammation. Jonathan reports:

… a molecule called C-reactive protein (CRP), easily measured by a simple and now ubiquitous blood test, could be used like a thermometer to take the temperature of a patient’s inflammation. Elevated CRP, he discovered years ago, predicts future cardiovascular events, including heart attacks.

Second, many of the benefits of exercise may come because of the long-run inflammation-reducing effects of exercise:

In 2007, [Harvard] associate professor of medicine Samia Mora and colleagues published a study of exercise that sought to understand why physical activity is salutary. They already knew that exercise reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease as much as cholesterol-lowering statin drugs do. … women had donated blood in the 1990s when they entered the study. Eleven years later, the researchers analyzed this frozen blood to see if they could find anything that correlated with long-term cardiovascular outcomes such as heart attack and stroke. “… reduced inflammation was the biggest explainer, the biggest contributor to the benefit of activity …”

The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise was much greater than most people had expected. That raised another question: whether inflammation might also play a dominant role in other lifestyle illnesses that have been linked to cardiovascular disease, such as diabetes and dementia.

In the short-run, exercise increases inflammation, just as it increases blood pressure. But in the long run, exercise reduces blood pressure and reduces inflammation.

Third, the case that inflammation rather than something else correlated with inflammation is doing the good work is bolstered by the many benefits of an anti-inflammatory drug:

In 2017, two cardiologists at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who suspected such a link, published the results of a human clinical trial that will forever change the way people think about inflammation. The trial, which involved more than 10,000 patients in 39 countries, was primarily designed to determine whether an anti-inflammatory drug, by itself, could lower rates of cardiovascular disease in a large population, without simultaneously lowering levels of cholesterol, as statin drugs do. The answer was yes. But the researchers went a step further, building into the trial additional tests seeking to clarify what effect the same anti-inflammatory drug, canakinumab, might have on illnesses seemingly unrelated to cardiovascular disease: arthritis, gout, and cancer. Only the researchers themselves, and their scientific colleagues, were unsurprised by the outcome. Lung cancer mortality dropped by as much as 77 percent. Reports of arthritis and gout also fell significantly.

Some of the researchers Jonathan interviewed speculate that strong immune system responses were very helpful in the environment of evolutionary adaptation, since infectious diseases were such a big danger.

Also, Jonathan interviewed Gökhan S. Hotamisligil, director of the Sabri Ülker Center for Metabolic Research. Gökhan speculated that eating all the time is one cause of chronic inflammation, both because eating puts a lot of reactive molecules in the mix and because being well-fed provides lots of energy to run the immune system.

Let me make connections to a few themes I have pursued in my diet and health posts. First, note how different an emphasis on inflammation is that a view that says “dietary fat is bad.” For example, if eating animal protein caused inflammation, the fat in the meat might get blamed instead of the animal protein in the meat. Second, if, as Gökhan argues, eating all the time causes excessive inflammation, could periodic fasting reduce inflammation? Third, reminiscent of, bit distinct, from what Gökhan is sayhing, I have written about Steven Gundry’s big claim that many particular foods cause inflammation and overactivate the immune system in “What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet.” Interestingly, Steven claims that certain types of food cause inflammation in and near the digestive tract, and that belly fat then builds up to provide a storehouse of energy for that immune-system response. If that is the case, then belly fat would be caused by inflammation rather than itself causing inflammation. But in any case, belly fat is a bad sign.

It is my sense that the importance of inflammation to the chronic diseases associated with obesity has not fully made it into popular awareness. It deserves to.

I have found the food insulin index extremely useful in thinking about which foods are healthy and which are unhealthy. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”) I would love to see a corresponding index of how much inflammation different foods. Short of that, I would love to have a better sense of what kinds of subjective sensations after eating are most likely to be signs of an inflammatory response to particular foods I just ate.

Overall, on what to do in relation to inflammation, diet and health, I am left with more questions than answers. There are many possible recommendations for which I am worried about possible side effects. As an analogy, too-easily-clotting blood is akin to an overactive immune system. A baby aspirin, turmeric or regular cinnamon (that is, non-Ceylon cinnamon) are all blood-thinners. Taking some kind of blood thinner may often make sense, but personally I find they give me nose bleeds. (I love cinnamon and eat Ceylon cinnamon to avoid the nose bleeds.) The three recommendations I do have in relation to inflammation that have few downsides are:

Exercise regularly.

Quit sugar. Heidi Turner says “Sugar is the universal inflammatory ... Everyone is sugar intolerant.” (See “Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is” and once you are convinced, turn to “Letting Go of Sugar.”)

Don’t eat all the time. (See “Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts.”)

Google “Steven Gundry Yes and No” and check out Steven’s list of OK “yes” foods and inflammatory “no” foods.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide.”

The People Have the Right to Erect a New Government When the Previous Government Betrays the Trust It Has Been Given

One of the most remarkable things John Locke says in his 2d Treatise on Government: Of Civil Government, in Chapter XIX, “Of the Dissolution of Government,” sections 219 to 221, is that the people may erect their own government either when the previous government has descended into anarchy, or when it has betrayed the people’s trust. He argues that the people have an inherent right to

… a settled [government], and a fair and impartial execution of the laws made by it.

(Here I have translated the noun “legislative” as “government.”) Besides anarchy, the people, he says, have a right to erect a new government when the previous government betrays its trust:

The legislative acts against the trust reposed in them, when they endeavour to invade the property of the subject, and to make themselves, or any part of the community, masters, or arbitrary disposers of the lives, liberties, or fortunes of the people.

If the people have this right, it is appropriate to make it possible for the people to exercise this right in a relatively low cost way. Democracy is one of the simplest—and in practice the most effective known way of lowering the cost of the people to exercise their right to erect a new government when the old one descends into anarchy or betrays the trust given to it.

Democracy in the real world is far from perfect. But it has this treat virtue: if the vast majority of people hate the government, then the government falls. Otherwise it is not a true democracy.

Even democracies in form that are not true democracies because the elections are rigged, still have some benefit in paying homage to the principle that if a government is horrible, the people get to replace it. And having a tradition of elections in form has, I believe, a positive effect on the likelihood of possible futures in which makes elections take full force. For example, who should be the successor in a dictatorship or semidictatorship is not always clear. Sometimes that question of succession will end up being resolved an election even though the elections before that were sham elections.

Moreover, in our world of 2019, elections have become a time when the rest of the world is watching. That is valuable.

If an autocracy really is looking after the welfare of the people (as most claim but do not do), then John Locke’s principle does not require democracy. But if an autocracy really is looking after the welfare of the people better than anyone else or any other organization would, it should be able to win an election. So if an autocracy is actually legitimate, there would be no harm to having a democracy instead, with the erstwhile autocrats being converted into election victors. (I don’t think John Locke would have any truck with the notion that the people are not good judges of their own welfare.) This way of looking at things does, however, suggest that one should not diss autocrats who genuinely govern putting the people’s welfare first and with high competence, then at some point institute elections and win them fairly.

In relation to these powerful ideas, it is well worth reading John Locke’s own words:

219. There is one way more whereby such a government may be dissolved, and that is, when he who has the supreme executive power neglects and abandons that charge, so that the laws already made can no longer be put in execution. This is demonstratively to reduce all to anarchy, and so effectually to dissolve the government: for laws not being made for themselves, but to be, by their execution, the bonds of the society, to keep every part of the body politic in its due place and function; when that totally ceases, the government visibly ceases, and the people become a confused multitude, without order or connexion. Where there is no longer the administration of justice, for the securing of men’s rights, nor any remaining power within the community to direct the force, or provide for the necessities of the public, there certainly is no government left. Where the laws cannot be executed, it is all one as if there were no laws; and a government without laws is, I suppose, a mystery in politics, unconceivable to human capacity, and inconsistent with human society.

§. 220. In these and the like cases, when the government is dissolved, the people are at liberty to provide for themselves, by erecting a new legislative, differing from the other, by the change of persons, or form, or both, as they shall find it most for their safety and good: for the society can never, by the fault of another, lose the native and original right it has to preserve itself, which can only be done by a settled legislative, and a fair and impartial execution of the laws made by it. But the state of mankind is not so miserable that they are not capable of using this remedy, till it be too late to look for any. To tell people they may provide for themselves, by erecting a new legislative, when by oppression, artifice, or being delivered over to a foreign power, their old one is gone, is only to tell them, they may expect relief when it is too late, and the evil is past cure. This is in effect no more than to bid them first be slaves, and then to take care of their liberty; and when their chains are on, tell them, they may act like freemen. This, if barely so, is rather mockery than relief; and men can never be secure from tyranny, if there be no means to escape it till they are perfectly under it: and therefore it is that they have not only a right to get out of it, but to prevent it.

§. 221. There is therefore, secondly, another way whereby governments are dissolved,and that is, when the legislative, or the prince, either of them, act contrary to their trust.

First, The legislative acts against the trust reposed in them, when they endeavour to invade the property of the subject, and to make themselves, or any part of the community, masters, or arbitrary disposers of the lives, liberties, or fortunes of the people.

For links to other John Locke posts, see these John Locke aggregator posts:

Hessler, Pöpping, Hollstein, Ohlenburg, Arnemann, Massoth, Seidel, Zarbock and Wenk: Availability of Cookies During an Academic Course Session Affects Evaluation of Teaching

Link to the abstract shown above. Hat tip to Chris Chabris.

In “False Advertising for College is Pretty Much the Norm” and “The Most Effective Memory Methods are Difficult—and That's Why They Work,” I discuss what I believe should be the main goal of college teaching: trying to encourage students to learn things that they can still remember a year or two later. But I have always thought that, in principle, how enjoyable the learning is could be an appropriate subsidiary goal. I have thought that typical course evaluations were more or less directed at measuring how enjoyable a learning experience was. But evidence from several quarters suggests that they are flawed measures even of that:

male students tend to rate female instructors lower than they rate male instructors without an obvious teaching quality difference

students who expect to get a better grade give higher ratings

provision of cookies raises ratings

Let’s dig more into the results from “Availability of cookies during an academic course session affects evaluation of teaching” by Michael Hessler, Daniel Poepping, Hanna Hollstein, Hendrik Ohlenburg, Philip H Arnemann, Christina Massoth, Laura M Seidel, Alexander Zarbock and Manuel Wenk.

They emphasize the institutional importance of course evaluations by students:

End-of-course feedback in the form of student evaluations of teaching (SETs) has become a standard tool for measuring the ‘quality’ of curricular high-grade education courses. The results of these evaluations often form the basis for far- reaching decisions by academic faculty staff, such as those involving changes to the curriculum, the promotion of teachers, the tenure of academic appointments, the distribution of funds and merit pay, and the choice of staff.

Structured as a randomized controlled trial, the statistical identification seems quite credible. The sample size was not huge, but bigger than many psychology experiments:

A total of 118 medical students in their fifth semester were randomly allocated to 20 groups. Two experienced lecturers, who had already taught the same course several times, were chosen to participate in the study and groups of students were randomly allocated to these two teachers. Ten groups (five for each teacher) were randomly chosen to receive the intervention (cookie group). The other 10 groups served as controls (control group).

Availability of cookies raised the scores on average by .38 of a standard deviation. The probability that this could happen by chance (the p-value) was 2.8%. The authors did not preregister an analysis plan, so they may well have done some searching over specifications to make their results look good. But this still provides suggestive evidence that cookies can raise ratings—something that should be confirmed or disconfirmed in a considerably larger sample. (See “Let's Set Half a Percent as the Standard for Statistical Significance.”) Administrators who encourage the use of student course evaluations should fund such a large study or be ashamed of themselves.

Let me throw out another hypothesis that deserves to be tested. I have a theory that students who feel an instructor has a heavy accent want to express that somehow on the course evaluation forms. If there isn’t a separate question early on in the course evaluation asking about the instructor’s accent, students will mark down other ratings in order to try to get across their displeasure at the heavy accent. This can easily be tested by randomizing evaluation forms to either have or not have an early question about accent within the same class by a non-native-English-speaking instructor.

The bottom line is that a lot more well-powered research should be done on things other than teaching quality that might affect course evaluations. Not taking these issues seriously would be a sign of college administrators who are not serious about learning and teaching.

Yascha Mounk on How Far Off We are from Understanding Our Political Adversaries →

The title of this post is a link. Hat tip to Greg Ransom. Sunday morning, June 23, Greg Ransom, who tweets under @takinghayekseriously, has a set of tweets with his confirmatory reaction. (Unfortunately, they are not threaded together, which is why I am giving you a time designation instead of a link to these specific tweets.)

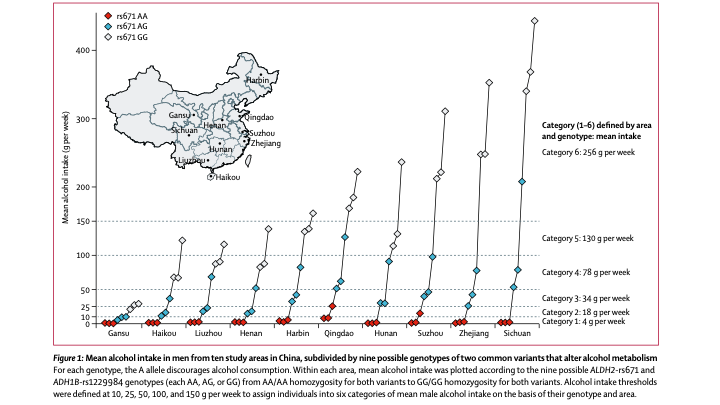

Data on Asian Genes that Discourage Alcohol Consumption Explode the Myth that a Little Alcohol is Good for your Health

Link to the Lancet article shown above. All images in this post are from this article.

Many people have taken comfort from news reports suggesting that moderate drinking is healthy. The top three graphs in the panel below, from a recent study of hundreds of thousands of Chinese drinkers and non-drinkers, confirm the kind of stylized facts that have led people to believe this. As the authors of “Conventional and genetic evidence on alcohol and vascular disease aetiology: a prospective study of 500 000 men and women in China” describe these results,

… conventional epidemiology showed that self-reported alcohol intake had U-shaped associations with the incidence of ischaemic stroke (n=14 930), intracerebral haemorrhage (n=3496), and acute myocardial infarction (n=2958); men who reported drinking about 100 g of alcohol per week (one to two drinks per day) had lower risks of all three diseases than non-drinkers or heavier drinkers.

But, one should be concerned that the U-shape in the top three graphs is generated by some combination of reverse causality and “Cousin Causality.” In the words of the authors (click here for the full paper, then click on the link to show all authors),

… poor health might affect alcohol consumption (reverse causality), and other systematic differences might exist between people with different drinking patterns that were not fully allowed for (residual confounding).

Fortunately for statistical identification, there are a pair of genes that have a big effect on drinking through well-understood biological pathways. Alcohol itself is mostly pleasant, but is ultimately turned into acetaldehyde, which is unpleasant until the acetaldehyde is in turn broken down into acetate, which is OK. Two gene variants in East Asia lead to a lot of acetaldehyde: one slows down the process of turning the unpleasant acetaldehyde (which causes flushing) into acetate; the other turns alcohol into acetaldehyde faster. Both make drinking less pleasant. Just below is the top of the explanatory box in the paper for this causal pathway:

Assuming these genes have no other substantial affect besides making alcohol consumption unpleasant, they can be used as instruments for alcohol consumption, allowing one to see the effects of alcohol without confounding from reverse causality or “Cousin Causality.” The relevance of these genes as statistical instruments can be seen from the graph below:

The authors have relative risk on the left-hand-side of the equation, put region of China as a control variable on the right-hand side of the regression, then effectively use region and genes as instruments for region and alcohol consumption. They do the analysis separately for men and for women. Since Chinese women in this study do not drink much regardless of their genes, the analysis for women is a good test of whether the genes affect health through pathways other than alcohol consumption. After correcting for multiple hypothesis testing (See “Who Leaves Mormonism?”), no effects of the genes are seen for women.

The results for six levels of alcohol consumption as predicted by region and genes can be seen below for men and women:

This evidence is quite persuasive. It seems unlikely that tinkering with the analysis in any appropriate way would yield a different result. Translating the outcome descriptions into simpler words, the analysis says that higher alcohol consumption in men leads causally to:

higher blood pressure

higher “good cholesterol”

a marker for liver disease

stroke

brain bleeding

There is no evidence of heart attack danger from drinking, but no evidence of protection from heart attack either.

Note that, while women help to verify that the gene variants don’t have big effects unrelated to alcohol, the low variation in alcohol consumption among these Chinese women (because few of them drink very much) means that there is little direct evidence here on the effects of alcohol on women. But many of the health effects of alcohol on women are likely to be similar to the health effects of alcohol on men.

The only shred of evidence for a physical health benefit from alcohol consumption is its effect in raising “good cholesterol.” But in their appendix, the authors give the first-stage regression of many health-related measures on the genes, and the news there is not good. For example, gene variant GG, which is associated with higher alcohol consumption than gene variant AG, fairly precisely predicts a body-mass index about .24 higher. Here is their full table for that first-stage regression on the genes:

Let me mention in closing that alcohol doesn’t seem to do its damage by causing an insulin spike. The insulin index data I discuss in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” gives a very low insulin index (less than five) to white wine and gin, and even beer only has a measured insulin index of 20. So the health harm from alcohol seems to come from other pathways, not from causing an insulin spike that would make you feel hungry afterwards.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide.”

Claudia Sahm's Anti-Recession Rule →

Also, don’t miss Noah Smith’s Bloomberg Opinion column on the Sahm Rule: “The Best Tools for Fighting Recession Run on Autopilot.”

Chris Kimball: Grief in the Journey

I am pleased to have another guest post on religion from my brother Chris. (You can see other guest posts by Chris listed at the bottom of this post.) Below are Chris’s words. When he writes “Church,” it means the Mormon Church, but those who have been in other churches or faiths may have had similar experiences.

I read a short article in Psychology Today titled “Four Types of Grief Nobody Told You About” (And why it’s important that we call them grief). I turned to the article out of curiosity and thinking about recent and not-so-recent deaths that affected me. What I found was surprisingly applicable to people I know in faith crisis. I generally prefer the term “faith journey” but the kinds of grief Sarah Epstein (the author) talks about refer me to the crisis part of the journey. I found it validating to see these described and recognized as important.

Here are the headers from the article, with my personal experience following. I fight the temptation to generalize, believing that these stories are best told in raw first person.

1. Loss of identity: A lost role or affiliation.

Being an active all-in Church member was an identity, a role, an affiliation. The loss of identity is hard. “Grief” seems like a good word. It is not a public grief, not dependent on other people knowing or any kind of formal change in membership or even attendance. Grief is about my own feelings. Sitting in a pew on Sunday knowing I don’t belong, knowing I will not be participating when others are called, knowing I am not the person I grew up thinking I was.

2. Loss of safety: The lost sense of physical, emotional, and mental well-being.

The loss of safety may not be obvious to an outside observer, but I have often observed that one of the things the Church “offers” (scare quotes because I believe it is a false promise) is a feeling of safety and that can be lost. Keep the commandments at the temple recommend level—which gets you into “the house of the Lord”—and you’re good. Get your children sealed to you, on a mission, married in the temple, and you will be together forever. So goes the promise.

When I started questioning the promise, one result was to feel unsafe. I remember getting up from my knees (almost 25 years ago) with the words fear and trembling in my mind: “From now on you live in the world of working out salvation with fear and trembling.” (Philippians 2:12)

For me, growing up in a fully active multi-generation family with a grandfather who was an Apostle, the Church felt like home. Felt like family. I no longer feel that. I feel like an outsider. Like I'm wearing a disguise when I take up space in a pew on Sunday morning.

Even though the overall process is one of growth and independence, I grieve the loss of “safe" and "home" feelings, even if they never were fully justified.

3. Loss of autonomy: The lost ability to manage one’s own life and affairs.

I’m not sure about the loss of autonomy. The faith crisis happened to me. I didn’t choose it. I didn’t go looking for trouble. That out-of-control feeling might well fit this loss-of-autonomy category. It may also show up as a frustration when I hear “just don’t think about it” or “choose to be faithful” and know that is so not helpful. My annoyed reaction underscores an inability to take charge and make it right.

However, that all happened years ago and subsequent events—a cancer diagnosis—overwhelmed any Church-related loss of autonomy in my life. I cannot manage my life, but the highlight in my head is an invader trying to kill me, not the Church.

4. Loss of dreams or expectations: Dealing with hopes and dreams going unfulfilled.

This one really strikes home. I grew up in the Church. I expected to graduate from seminary. I did. I expected to go on a mission. I did. I expected to marry in the temple. I did. I expected to have normal sorts of callings and live much of my life inside the Church. I did . . . until age 40. I expected to hit an early retirement and spend most of the rest of my life in Church service. However, at around age 40, I realized with crystal clarity that I was stepping off the path. That my future was unknown except that it would not be what I grew up expecting.

A lot of years have passed since I got up off my knees with an uncertain future, but it is not quite as simple as water under the bridge. My cousin and his wife—almost exactly my age—are mission president now in Japan Fukuoka. I think about what might have been. There are several ways it never would have worked (including my health), but “what might have been” doesn’t go easy. It is a loss and I hurt.

In the big picture I am happy and enjoying my second life. But the grief is there too. I have lost an identity, I have lost a sense of safety, I have lost control over my life, and I have lost dreams and expectations. I am better for naming and recognizing, but that doesn't make it all better.

Don't miss these posts on Mormonism:

The Message of Mormonism for Atheists Who Want to Stay Atheists

How Conservative Mormon America Avoided the Fate of Conservative White America

The Mormon Church Decides to Treat Gay Marriage as Rebellion on a Par with Polygamy

David Holland on the Mormon Church During the February 3, 2008–January 2, 2018 Monson Administration

Also see the links in "Hal Boyd: The Ignorance of Mocking Mormonism."

Don’t miss these other guest posts by Chris:

Christian Kimball: Anger [1], Marriage [2], and the Mormon Church [3]

Christian Kimball on the Fallibility of Mormon Leaders and on Gay Marriage

In addition, Chris is my coauthor for

Don’t miss these Unitarian-Universalist sermons by Miles:

By self-identification, I left Mormonism for Unitarian Universalism in 2000, at the age of 40. I have had the good fortune to be a lay preacher in Unitarian Universalism. I have posted many of my Unitarian-Universalist sermons on this blog.

The Tree of Life Web Project: A Cool Website Implementing a Giant Cladogram →

The Wikipedia article “Cladogram” explains cladograms this way:

A cladogram uses lines that branch off in different directions ending at a clade, a group of organisms with a last common ancestor.

Thus, a cladogram tells a lot about what we know about the evolution of different species.

The link above starts with Amniota, the narrowest clade that includes both us and our cousins the dinosaurs. The home page, with a link to the root of the tree, is here.

JP Koning on Ill-Considered Government Policies Standing in the Way of the Emergence of the Digital Cash that Can Eliminate Any Lower Bound on Interest Rates

I have always been impressed with JP Koning, both for his blog Moneyness and for the insights he has on Twitter. Now he is also posting fascinating pieces on the website of the American Institute for Economic Research. I show two above, with links at the bottom of screenshots. These two share the theme of government agencies—without sufficient thought—standing in the way of the development of the digital cash that could reduce the footprint of physical cash and thereby make it easier to neutralize any tendency of paper currency to create a lower bound on interest rates. (See “Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball—Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide.”)

Let me back up the claim that they are doing this without sufficient thought. First, the Financial Action Task Force, in its desire to make an easy trail of cryptocurreny transactions for law enforcement is ignoring the benefit of drawing people away from physical cash transactions that leave much less of a trail. It would be a different matter if we were eliminating physical cash (or allowing only heavy coins) for the sake of crime control, as Ken Rogoff recommends in The Curse of Cash. But as long as we leave physical cash unconstrained, we should try to make digital cash a more attractive option, since when necessary, it can be tracked more easily than physical cash.

Second, the Fed is worried that access by narrow banks to reserve accounts will lead to a lower bound on rates that will be contractionary. The solution is simple: the Fed can and should lower the interest rate on reserves very quickly in such situations. There should always be a quantitative trigger in place that instantly lowers the interest on reserves if reserves suddenly and unexpectedly go up. Or a good substitute is to have a quantitative ceiling on reserves, but provide a repo facility for funds beyond that, with the rate on the repo facility allowed to go down instantly if there is a surge of funds into it. (See “How to Keep a Zero Interest Rate on Reserves from Creating a Zero Lower Bound.”)

During times when the Fed is trying to keep the economy from overheating, allowing narrow banks to put money into an interest-bearing reserve account helps to keep interest rates up. One thing the Fed might worry about is that keeping deposit rates up would reduce bank profits. Lower bank profits could lead to lower bank capital in a proximate sense. But there are many other ways for banks to keep their net worth’s high to enhance financial stability, such as not paying dividends until they are stable. If these other financial stability measures lead to lending rates being higher, the Fed can just cut rates overall. (See “Why Financial Stability Concerns Are Not a Reason to Shy Away from a Robust Negative Interest Rate Policy.”)

And if ending the ‘tax’ on depositors and ‘subsidy’ to banks and borrowers implicit in banks being able to get away with low deposit rates is a serious policy concern (which I don’t believe for a minute), legislation should increase the existing explicit tax on depositors and explicit tax breaks for banks and borrowers rather than using oligopolistic low rates for bank depositors as a sneaky way of doing this. Remember, allowing narrow banks the same privileges as regular banks is a way to increase competition in a safe way. It is rare for increased competition to be a bad thing, especially after the Fed has used interest rate policy to get the economy to the natural level of output given that level of competition.

Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide

Bread and Fruit Dish on a Table, 1909 by Pablo Picasso. Two of the more controversial pieces of advice in the links below are to cut bread out of your diet and to eat fruit sparingly.

The list of links to my posts on diet and health has become too long to continue putting at the bottom of each new diet and health post. So I’ll refer to this post for a categorized list of those links. (I’ll keep it updated.) Take a good look at the list. I have high hopes that in it, you can find something useful to you.

I. The Basics

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

Jonathan Shaw: Could Inflammation Be the Cause of Myriad Chronic Diseases?

George Monbiot on the Role of Food Companies in Making Us Fat

Nicole Rura: Close to Half of US Population Projected to Have Obesity by 2030

Are Processed Food and Environmental Contaminants the Main Cause of the Rise of Obesity?

II. Fasting

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

How to Make Ramadan Fasting—or Any Other Religious Fasting—Easier

Elizabeth Thomas: Can Time-Restricted Eating Prevent You From Overindulging on Thanksgiving?

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

The Benefits of Fasting are Looking So Clear People Try to Mimic Fasting without Fasting

On My Pattern of Fasting (click here, then on ‘show this thread’)

Potential Protective Mechanisms of Ketosis in Migraine Prevention

Can a Fasting-Induced Changing-of-the-Guard for Immune Cells Help Treat Auto-Immune Diseases?

III. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

The Better Side of Conventional Wisdom about Diet and Health

How Many Thousands of Americans Will the Sugar Lobby's Latest Victory Kill?

Aseem Malhotra: Avoiding Sugar is Much More Powerful Than Taking Statins (link post)

Sam Apple on the Tragedy of Pro-Sugar Policies of the US Government

IV. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

Cancer Cells Love Sugar; That’s How PET Scans for Cancer Work

V. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Vitamin D Seems to Help If You Have Non-Alcoholic Liver Disease

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

Don't Drink Sweet Drinks Between Meals—Whether Sugary or with Nonsugar Sweeteners

Elizabeth Thomas: Can Time-Restricted Eating Prevent You From Overindulging on Thanksgiving?

On Franziska Spritzler’s 14 Ways to Lower Your Insulin Levels

VI. Calories In/Calories Out

On How Incredibly Noisy Any One Reading on the Scale is as a Gauge of Long-Run Weight Gain or Loss

Kevin D. Hall and Juen Guo: Why it is so Hard to Lose Weight and so Hard to Keep it Off

VII. Other Health Issues

Hormone Replacement Therapy is Much Better and Much Safer Than You Think

Standard Hormone Replacement Therapy Doesn't Cause Breast Cancer

How the Ancient Greeks Invented Eye Movement Desensitizing and Reprocessing to Deal with Trauma

Judson Brewer, Elizabeth Bernstein and Mitchell Kaplan on Finding Inner Calm

Less Than 6 or More than 9 Hours of Sleep Signals a Higher Risk of Heart Attacks

Mental Retirement: Use It or Lose It—Susann Rohwedder and Robert Willis

Geriatrics: The Grim Good Magic of Setting Priorities in Old Age

Matthew Sedacca: To a Cigarette Maker, Your Life Is Worth About $10,000

Improving Your Blood Vessel Health by Strengthening Your Breathing Muscles

Should Those Whose Main Symptom is Chest Pains Get Stent or Bypass Surgery?

An Inexpensive Cold Sore Treatment That Doubles as an Antiseptic Towelette

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and Drinks

Don't Think Fat vs. Carbs vs. Protein; It's Good vs. Bad Fat, Carbs and Protein

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

The Artery-Aging Properties of TMAO and the TMAO-Producing Effect of Animal Protein Consumption

The Surprising Genetic Correlation Between Protein-Heavy Diets and Obesity

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Journal of the American College of Cardiology State-of-the-Art Review on Saturated Fats

IX. Wonkish

Are Processed Food and Environmental Contaminants the Main Cause of the Rise of Obesity?

Livestock Antibiotics, Lithium and PFAS as Leading Suspects for Environmental Causes of Obesity

How Lithium May Have Led to Serious Obesity for the Pima Beginning around 1937

Market Opportunities for Helping People Deal with Obesity-Causing Environmental Contaminants

Semaglutide Looks Like the First Truly Impressive Weight-Loss Drug

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

America’s Losing Battle Against Diabetes—Chad Terhune, Robin Respaut and Deborah Nelson (link post)

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

In Mice, High-Fat Diets Seem to Foster Cancers Involving Immune Cells

Frightening New England Journal of Medicine Projections for the Rise of Obesity

David Ludwig's 6-Minute Summary of the Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity

You Might Need to Educate Your Doctor about the Effects of a Long Fast on Cholesterol Readings

Standard Cholesterol Tests are Substandard; Better Cholesterol Tests are Available

X. Gary Taubes

XI. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XII. Pandemic Thoughts on Diet and Health

Getting More Vitamin D May Help You Fight Off the New Coronavirus

Shelly Miller: Indoors is the Danger Zone for COVID-19 Transmission; Good Ventilation Can Help

Indoors is Very Dangerous for COVID-19 Transmission, Especially When Ventilation is Bad

Jose-Luis Jimenez on the Benefits of Masks and Being Outdoors

XIII. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.” I defend the ability of economists like me to make a contribution to understanding diet and health in “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’” and “Crafting Simple, Accurate Messages about Complex Problems.”