Kevin D. Hall and Juen Guo: Why it is So Hard to Lose Weight and So Hard to Keep it Off

As an economist, I love Kevin Hall’s and Juen Guo’s approach to energy balance and weight loss. In their paper “Obesity Energetics: Body Weight Regulation and the Effects of Diet Composition,” they emphasize right away that calories in and calories out are endogenous:

Weight changes are accompanied by imbalances between calorie intake and expenditure. This fact is often misinterpreted to suggest that obesity is caused by gluttony and sloth and can be treated by simply advising people to eat less and move more. …

Obesity is often described as a disorder of energy balance arising from consuming calories in excess to the energy expended to maintain life and perform physical work. While this energy balance concept is a useful framework for investigating obesity, it does not provide a causal explanation for why some people have obesity or what to do about it.

In particular, obesity prevention is often erroneously portrayed as a simple matter of bookkeeping whereby calorie intake must be balanced by calorie expenditure.1 Under this “calories in, calories out” model, treating obesity amounts to advising people to simply eat less and move more, thereby tipping the scales of calorie balance and resulting in steady weight loss that accumulates according to the widely known, but erroneous, 3500 kcal per pound rule.2,3 Therefore, failure to experience substantial weight loss implies that an individual lacks the willpower to adhere to a modest lifestyle intervention over a sufficient period of time.

Then they detail evidence on different mechanisms by which calories in and calories out might depend on weight so that while improving one’s dietary habits can change the level of one’s weight, there is a new equilibrium at a lower weight that can only be maintained by continuing those better dietary habits: permanent weight loss requires permanent changes in behavior.

How Calories Out Depend on Weight. There are three components of calories out. First is inefficiency in converting all the calories in food into generally usable energy for the body. This is called the thermic effect of food because heat is the form in which energy that is not generally usable shows up. (Obviously, there are situations in which body heat is itself useful.) In addition to the thermic effect of food, there is resting energy expenditure and physical activity energy expenditure. Physical activity expenditure can, in turn, be divided into exercise calories and spontaneous physical activity calories.

The Thermic Effect of Food. One of the big points Kevin and Juen make is that a highfat lowcarb diet does not increase the thermic effect: in their meta-analysis, there is a tiny difference in the opposite direction. In other words, the evidence I discussed in “Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories” is outweighed by the evidence in other studies.

One confounding factor is that the thermic effect of protein is greater than the thermic effect of either fat or carbs. However, this doesn’t mean you should ramp up your protein consumption. Protein—particularly animal protein—has other issues for health:

(Also, there are reasons to worry about soy.)

The thermic effect of food is not that large: Kevin and Juen write “For typical diet compositions, the thermic effect of food is approximated to be about 10% of energy intake.” As a percentage of energy intake, this dimension of calories out is likely to go down when one eats less. Some other metabolic components of energy expenditure might get counted as part of resting energy expenditure. These metabolic components should follow a similar pattern to the thermic effect of food.

One of the things I am confused about is where the energy burned by gut bacteria that doesn’t make it to the human host figures into this typology of calories out. Also, on the other side, what about certain types of gut bacteria taking calories that were indigestible by humans (and so usually not included in the usual calorie counts) and turn them into humanly usable calories?

Resting Energy Expenditure. Other thing equal, the more you weigh, the higher the resting energy expenditure. So when you get to a lower weight, this dimension of calories out is likely to go down.

Physical Activity Energy Expenditure. It takes a lot of energy to move a heavy body. Conversely, the lighter you are, the fewer calories any given amount of activity uses. Kevin and Juen write: “physical activity energy expenditure declines with weight loss unless its quantity or intensity increases to compensate.”

Exercise. While exercise increases energy expenditure during exercise, it may lead to less energy expenditure the rest of the day. Here is how Kevin and Juen put it:

While often considered a first-line treatment option for obesity, large amounts of exercise are required to result in a modest degree of average weight loss.15 However, exercise results in preferential loss of body fat and maintenance of fat-free mass compared with diet-induced weight loss.16,17 but exercise does not appear to prevent the slowing of metabolic rate during weight loss.18 Exercise interventions typically result in less average weight loss than expected, based on the exercise calories expended, and individual weight changes are highly variable even when exercise is supervised to ensure adherence.19 A likely explanation for these observations is that the energy expended during exercise is variably compensated by changes in food intake and non-exercise physical activity behaviors.19

The recently proposed “constrained energy expenditure model” provides an alternative explanation for why exercise interventions often result in minimal weight loss.20 According to this model, daily energy expenditure is regulated and increments in physical activity expenditure are predicted to be offset by decreases in non-physical activity expenditure (ie, the thermic effect of food or REE) resulting in minimal energy imbalance. The experimental basis of the constrained energy expenditure model in humans includes cross-sectional data demonstrating that free-living daily energy expenditure adjusted for body composition is relatively constant for a wide range of physical activity levels measured using accelerometry.21,22 Furthermore, longitudinal data have found that progressive increases in the quantity and intensity of aerobic exercise training do not lead to corresponding increases in total daily energy expenditure in ad libitum-fed men and women.23

Effects of Calories In on Calories Out. Even apart from weighing less, the less you eat, the fewer calories you burn. The body could conserve energy by either reducing resting energy expenditure or reducing physical activity energy expenditure (perhaps mostly spontaneous physical activity, which is harder to notice than exercise). Kevin and Juen write: “Reductions in energy intake lead to decreased energy expenditure to a degree that is often greater than expected based on changes in body composition or the thermic effect of food.25,26”

Effects of Weight Loss on Appetite. A lower weight can result in a higher appetite that can easily lead to more food intake. The article below, “How strongly does appetite counter weight loss? Quantification of the feedback control of human energy intake” by David Poldori, Arjun Sanghvi, Randy Seeley and Kevin R. Hall showed this in an ingenious way. A drug that was being tested in a placebo-controlled clinical trial lead to quite a bit of blood sugar being excreted in the urine. So those who got the real drug had a reduction in calories in net of that excretion of blood sugar. Those who lost blood sugar lost more weight than those on the placebo, and ate more the more weight they lost. One caveat is that the amount of food intake was imputed from a model rather than directly measured.

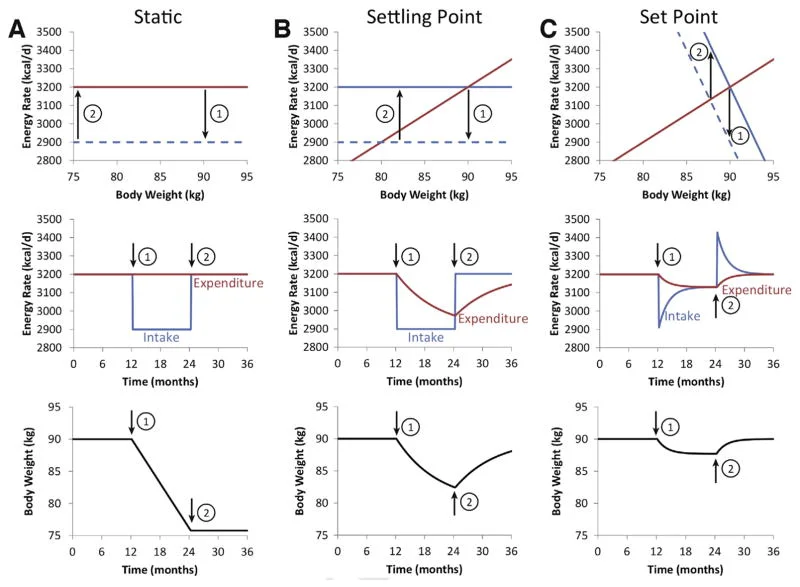

The Determination of Equilibrium Weight. All of these effects go in the same direction in terms of the qualitative behavior of body weight. They mean that a particular set of overall eating habits (aside from things governed by appetite in ways people don’t realize) and exercise habits corresponds to an equilibrium weight. Changing one’s eating and exercise habits changes that equilibrium weight. But if one goes back to the old habits, the original equilibrium weight will again apply. (In an economic analogy, weight is like the capital stock in a Solow growth model, not like the capital stock in the AK model.) In the graphs below, taken from Kevin and Juen’s paper, economists will find the top row the most familiar way to think about equilibrium. The column on the left shows what would happen if lower weight had no effect on either calories in or calories out. The middle column shows what happens if calories out go down as weight goes down. The column on the right shows what happens if calories out go down as weight goes down and calories in go up as weight goes down. In both the middle and right columns, there is an equilibrium weight for any set of eating and exercise habits. Going back to the old habits leads back to the old weight. Maintaining a new lower weight requires permanently different habits.

Hope for Dramatic, Permanent Weight Loss. One intervention that Kevin and Juen do not talk about in their paper is a change in the timing of eating as an intervention, whether that means a short eating window within each day or some use of longer fasts (periods of time without eating but still drinking water). What they do is provide ample reason why interventions short of changing the time pattern of one’s eating have such a tough time delivering permanent weight loss. Here is their conclusion:

In addition to the long-term feedback control of energy intake mediated by homeostatic signals related to body weight and composition, eating behavior is also strongly influenced by social and environmental influences in conjunction with learned eating habits.73,74 While previous conceptions of the set point model were thought to be incompatible with non-homeostatic influences on food intake and body weight,72 such effects can be naturally incorporated by altering the position or slope of the energy intake line depicted in Figure 3A and the defended body weight will be adjusted accordingly.

Unfortunately, we do not yet know the quantitative effects of non-homeostatic influences on the set point model, but there is likely to be a wide degree of individual variation. Some people may experience substantial changes in the energy intake, along with correspondingly large weight changes, whereas others will be more resistant. Re-engineering the social and food environments may facilitate shifts in the energy intake line, but losing weight and keeping it off using willpower alone to reduce energy intake is difficult because considerable effort is required to persistently resist the physiological adaptations that act to increase appetite and suppress energy expenditure.

I want to focus attention on the hypothesis that one of the most important aspects of the “social and food environment” is our customs about the timing of eating: the idea that it is normal to have three meals a day, every day, with snacking being OK. Question that social norm, and there is hope for dramatic, permanent weight loss.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.