Sutton, Beyl, Early, Cefalu, Ravussin and Peterson: Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes

Image source: the article shown below

The topics of my diet and health posts often touch on areas where research is sorely lacking. One bright spot in the research outlook is that a great deal of research is being done on short-term fasting. The introductory paragraph to the June 2018 Cell Metabolism article “Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes” by Elizabeth F.Sutton, Robbie Beyl, Kate S. Early, William T. Cefalu, EricRavussin, and Courtney M.Peterson gives a nice rundown of recent work in this area. To make the paragraph easier to read, I have bolded everything that is not a list of citations:

Intermittent fasting (IF)—the practice of alternating periods of eating and fasting—has emerged as an effective therapeutic strategy for improving multiple cardiometabolic endpoints in rodent models of disease, ranging from insulin sensitivity and ectopic fat accumulation to hard endpoints such as stroke and diabetes incidence (Antoni et al., 2017, Harvie and Howell, 2017, Mattson et al., 2017, Patterson and Sears, 2017). The first clinical trials of IF in humans began about a decade ago, including trials on alternate-day fasting (Catenacci et al., 2016, Heilbronn et al., 2005a, Heilbronn et al., 2005b), alternate-day modified fasting (ADMF) (Bhutani et al., 2013, Eshghinia and Mohammadzadeh, 2013, Halberg et al., 2005, Hoddy et al., 2014, Hoddy et al., 2016, Johnson et al., 2007, Klempel et al., 2013, Kroeger et al., 2018, Soeters et al., 2009, Trepanowski et al., 2017a, Trepanowski et al., 2017b, Varady et al., 2009, Varady et al., 2013, Wegman et al., 2015), the 5:2 diet (Carter et al., 2016, Harvie et al., 2011, Harvie et al., 2013, Harvie et al., 2016), and the fasting-mimicking diet (Brandhorst et al., 2015, Choi et al., 2016, Wei et al., 2017, Williams et al., 1998). Data from these trials suggest that IF has similar benefits in humans: IF can reduce body weight or body fat, improve insulin sensitivity, reduce glucose and/or insulin levels, lower blood pressure, improve lipid profiles, and reduce markers of inflammation and oxidative stress (Bhutani et al., 2013, Brandhorst et al., 2015, Carter et al., 2016, Catenacci et al., 2016, Eshghinia and Mohammadzadeh, 2013, Halberg et al., 2005, Harvie et al., 2011, Harvie et al., 2013, Harvie et al., 2016, Heilbronn et al., 2005a, Heilbronn et al., 2005b, Hoddy et al., 2014, Hoddy et al., 2016, Johnson et al., 2007, Klempel et al., 2013, Trepanowski et al., 2017b, Varady et al., 2009, Varady et al., 2013, Wegman et al., 2015, Wei et al., 2017, Williams et al., 1998).

I find the topic of “early time-restricted feeding” especially interesting because my typical pattern qualifies as “early time-restricted feeding”: on days when I am working at home, I try to have an eating window from about 11 AM to 3 PM. Sutton, Beyl, Early, Cefalu, Ravussin and Peterson give this summary of previous research on time-restricted feeding (TRF) in general (again I have bolded everything that is not citations):

TRF is a type of IF that extends the daily fasting period between dinner and breakfast the following morning, and, unlike most forms of IF, it can be practiced either with or without reducing calorie intake and losing weight. Since the median American eats over a 12-hr period (Kant and Graubard, 2014), we define TRF as a form of IF that involves limiting daily food intake to a period of 10 hr or less, followed by a daily fast of at least 14 hr. Studies in rodents using feeding windows of 3–10 hr report that TRF reduces body weight, increases energy expenditure, improves glycemic control, lowers insulin levels, reduces hepatic fat, prevents hyperlipidemia, reduces infarct volume after stroke, and improves inflammatory markers, relative to grazing on food throughout the day (Belkacemi et al., 2010, Belkacemi et al., 2011, Belkacemi et al., 2012, Chung et al., 2016, Duncan et al., 2016, García-Luna et al., 2017, Hatori et al., 2012, Kudo et al., 2004, Manzanero et al., 2014, Olsen et al., 2017, Park et al., 2017, Philippens et al., 1977, Sherman et al., 2011, Sherman et al., 2012, Sundaram and Yan, 2016, Woodie et al., 2017, Wu et al., 2011, Zarrinpar et al., 2014). We chose to test TRF over other forms of IF in part because TRF consistently improves health endpoints in rodents, even when food intake and/or body weight is matched to the control group (Belkacemi et al., 2012, Hatori et al., 2012, Olsen et al., 2017, Sherman et al., 2012, Woodie et al., 2017, Wu et al., 2011, Zarrinpar et al., 2014).

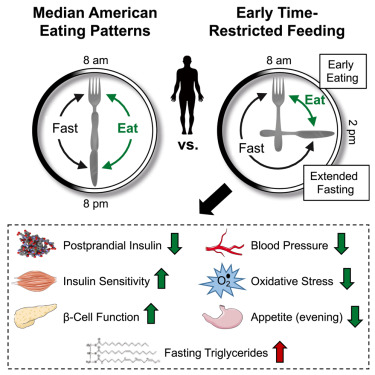

The four previous human trials of a short eating window suggested that restricting eating to the middle of the day yielded good outcomes, while restricting eating to the end of the day didn’t improve things that much. So Sutton, Beyl, Early, Cefalu, Ravussin and Peterson decided to study early time-restricted feeding (eTRF). They also made three other key decisions. First, they wouldn’t try to study whether people could adhere to a short eating window on their own, nor would they try to keep people in the metabolic ward. They used the in-between procedure of insisting study participants eat only food provided by the study staff and only in the presence of one of the study staff. Second, they were looking for health benefits that occurred even without any weight loss, and so gave participants enough food to keep their weight constant. Third, in their crossover study, each participant ate the same 3 meals each day over a 6-hour early eating window each day for 5 weeks as they ate each day over a 12-hour eating window for five weeks. The order of these two 5-week periods was randomized, and the two 5-week periods were separated by a 7-week washout period.

Unfortunately, they had a sample-size of only 8. They did find some good hints of effects across many measures, though. This that they mention in their abstract is only some of the results: “eTRF improved insulin sensitivity, β cell responsiveness, blood pressure, oxidative stress, and appetite.”

Another limitation of their study is that for at least 3 of the 5 weeks, study participants wouldn’t have been fully adapted to burning body fat during their 18-hours of no food. Fasting even 18 hours can be stressful on the body when one has not yet made the transition to metabolizing fat instead of carbs. (See my post “David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet.” Burning body fat is likely to be similar metabolically to a highfat diet.)

I don’t find the restriction of their sample to people with prediabetes a serious limitation: a larger share of everyone who is overweight has some degree of insulin resistance, which is the key dimension of prediabetes. The limitation to only men with no women is a more serious limitation.

I find the comments the authors make about feasibility and acceptability interesting:

Participants also reported that the challenge of eating within 6 hr each day was more difficult than the challenge of fasting for 18 hr per day (difficulty scores: 65 ± 20 versus 29 ± 18 mm; p = 0.009). In fact, all but one participant reported that it was not difficult or only moderately difficult (<50 mm on a 100-mm scale) to fast for 18 hr daily.

This matches my experience. Not eating at all is relatively easy, and it is hard to overeat in a short eating window.

It is fortunate that much more research on fasting is on its way.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.