Reexamining Steve Gundry's `The Plant Paradox’

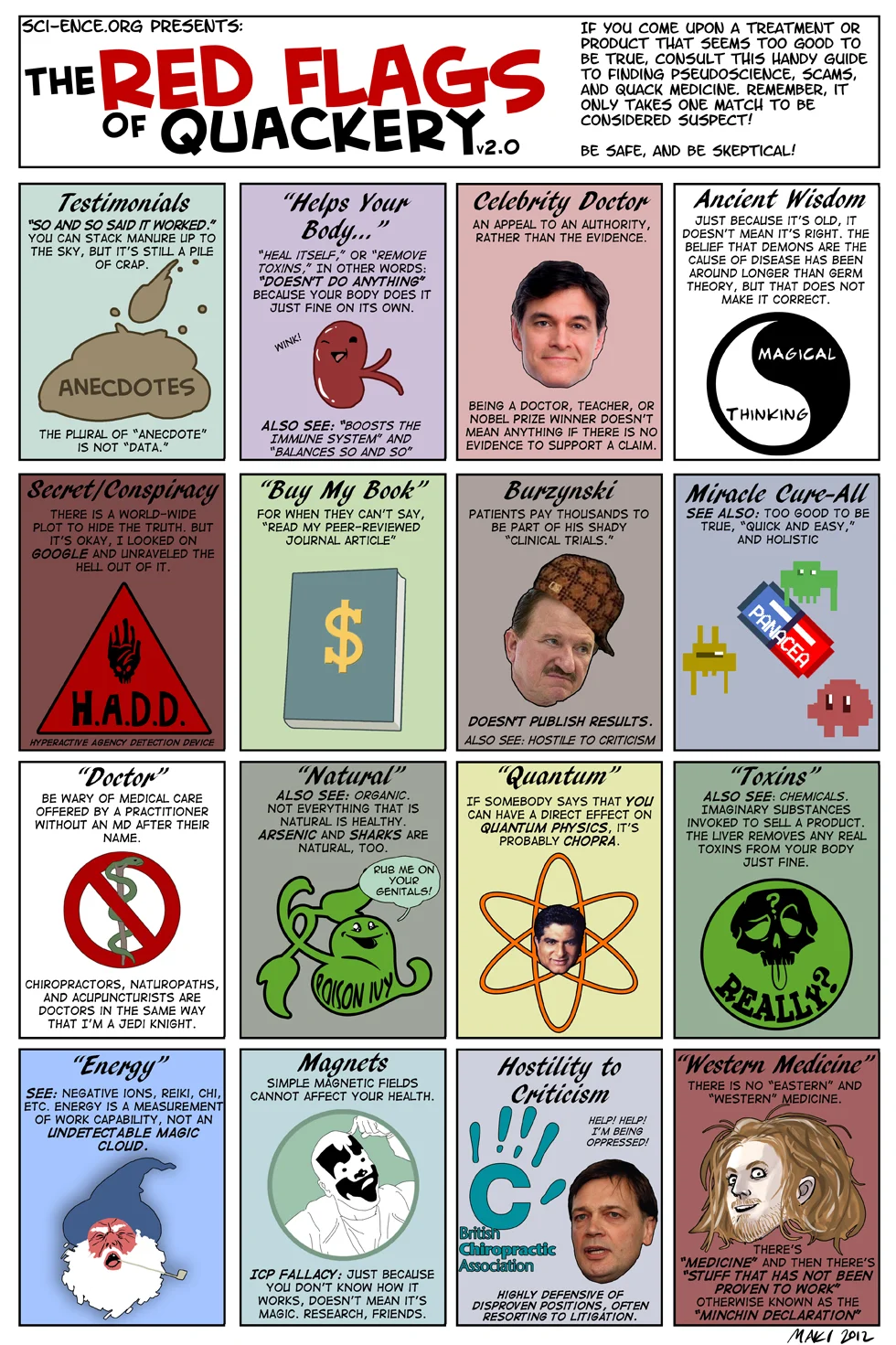

Image source. Is Steven Gundry a quack? No. He has reasonable hypotheses, then exaggerates the degree of current support for those hypotheses. He cannot be fully trusted, but his ideas should not be dismissed without much better evidence than we have now.

My son Jordan challenged me to revisit my views on Steven Gundry’s book The Plant Paradox. In order to revisit those views, I googled around to find blog posts and articles online that were critical of Gundry and followed the links. I’ll insert images of these blog posts and articles where I discuss each.

There are two parts to this reexamination of Steven Gundry’s book The Plant Paradox.. One is to revisit the key hypotheses I emphasized in my blog post review of The Plant Paradox: What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet. These I summarized as follows:

The War Between Plants and Animals. This is the idea that many of the natural insecticides plants produce to avoid getting eaten quite as often may have negative effects on human health.

Old and New Natural Insecticides: We and Our Gut Microbiome Have Evolved to Deal With Some Natural Insecticides, But Not Others. This is a key qualification: humans and their gut microbes should have evolved to deal with the natural insecticides from plants that our ancestors have eaten for a hundred thousand years or more, with some significant adaptation to deal with these natural insecticides for things our ancestors have eaten for ten thousand years or more.

More generally, apart from natural insecticides, the longer our ancestors have eaten a particular type of food, prepared in the way it is now prepared, the more assurance we have of its safety. Overall, the dietary there are at least four big dietary changes evolution may not have fully adapted us for:

The Agricultural Revolution, with its Emphasis on Grain

The A-1 Mutation in Cows, which Affects Milk Proteins

The Introduction of New World Plant Food

Highly Processed Food

The other views based on The Plant Paradox to reexamine are Steven Gundry’s claims about specific foods.

Note that none of this about the particular class of natural insecticides called “lectins” in general being bad, which is, I think, a distortion of Steven Gundry’s views, and certainly not something I would agree with. Lectins in foods that humans and their gut microbes have had plenty of time to adapt to should be fine. (The exception to the idea that truly ancient foods should be safe for the typical person is that one might have problems if one’s dietary patterns and other environmental factors had killed off a large share of the types of microbes that are important for dealing with the lectins in those foods.)

I view all of these claims are important hypotheses that have not been falsified by existing data. One already meets with a general consensus by scholars: (4) the idea that the highly processed food so common in modern diets is quite bad for us. I write about why in “The Problem with Processed Food.”

Another claim for which I consider the evidence to be strong—though not gold-standard evidence—is (2) the claim that A-1 milk is a problem. On that, see my posts

On claim (1), Grain is generally a problem because of its high insulin index. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”) Whether it is also a problem because of lectins is more speculative. This matters a lot for oatmeal, which is one of the grains that is lowest on the insulin index. I don’t know what to think about oatmeal. Because it is relatively low on the insulin index and has some components that are especially satiating, oatmeal has some real benefits for weight loss that may outweigh whatever lectin dangers it presents.

(Rice is fairly high on the insulin index; for rice there is a mystery about why eating a lot of rice hasn’t led to more obesity in East Asia. I certainly feel very hungry a couple of hours after I eat any substantial amount of rice. I don’t know the answer to why heavy rice-eating hasn’t led to more obesity among East Asians, especially in the context of increasing available of food to eat if the insulin kick from rice makes them hungry. I wish I knew. Two possibilities that don’t seem sufficient to explain the puzzle are (a) Jason Fung suggests that eating sour things with rice as the Japanese do at least at some meals might reduce the insulin kick from rice, (b) natural selection may have given many East Asians adaptations for rice eating—maybe, maybe such adaptations are easier than for other grains. As far as lectins go, white rice may not be very high in lectins.)

Claim (3), that new world plant food is likely to be problematic, is an especially interesting claim. Near the end of this post, I discuss tomatoes in some detail. Potatoes, like grain, are quite high on the insulin index, so I think potatoes are very unhealthy quite apart from lectins. But it is possible that lectins make them worse. Steven Gundry has gotten me worried about cashews and peanuts.

Link to the review shown above. I only know it was written by Stephen Guyenet because of the link to it in Joel Kahn’s post “Eat Your Beans but Skip Reading Dr. Steven Gundry’s ”The Longevity Paradox”: Flaws and Fruits.”

As for the other hypotheses, Stephen Guyenet agrees with me on that. In the post shown above, he repeatedly indicates his interest in these hypotheses as hypotheses, and writes:

We believe the ideas in this book should have been presented as hypotheses to be tested rather than as scientific findings.

He rates the following claims by Steven Gundry on a 0 to 4 scale as follows (I combined the text of the claim as summarized by Stephen Guyenet with the rating he gives a few paragraphs later.)

Claim 1: Lectins from grains, legumes, certain types of dairy, fruit, and nightshade and cucumber-family vegetables cause an increase in intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”). Rating: 1.7 out of 4.

Claim 2: Grains, legumes, certain types of dairy, fruit, and nightshade and cucumber-family vegetables are fattening foods because their high content of lectins stimulate energy storage and appetite. Rating: .7 out of 4.

Claim 3: Inside the body, lectins from grains, legumes, certain types of dairy, fruit, and nightshade and cucumber-family vegetables cause chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions leading to a wide range of chronic diseases. 1 out of 4.

On Claim 2, I need to say that I never found Steven Gundry’s claim that nightshades and cucumber-family vegetables are fattening very convincing. (I have worried about them being harmful in ways other than their being fattening.) Grains (even whole grains), legumes and fruit can be fattening simply because they are somewhat high on the insulin index, which need not have much to do with lectins. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”) Given the number of patients that Steven Gundry has seen who have chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions, and has treated with dietary restrictions, I give a fair amount of credence to the interrelated Claims 1 and 3. I agree with Stephen Guyenet that if this is indeed true, Steven Gundry needs to publish peer-reviewed articles backing up what he claims he sees in his patients with chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions. If he doesn’t do so, someone else should test this. It is an important enough and credible enough claim to be worth either falsifying or confirming, whatever a careful study would show.

(Interestingly, Stephen Guyenet’s tone in discussing Steven Gundry’s highly speculative hypotheses is much more friendly than his discussion of Gary Taubes’s claim that sugar is very, very, very bad—a claim that has much better evidence to back it up. See “The Case Against Sugar: Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes” and “Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast).” One possible reason for the difference in tone is that Steven Gundry, as a medical doctor, is much more “in the guild” than Gary Taubes, who is a journalist with physics training.)

Stephen Guyenet, like many others questioning Steven Gundry’s claims, points to abundant evidence that whole grains, legumes, fruit, nightshades and cucumber-family vegetables help reduce obesity and lead to other good outcomes. There is a very basic point to make here. Oversimplifying, suppose you could rank all foods (perhaps within category), from most health to least healthy. Given the fact that a large share of people are eating very unhealthy foods, if medium unhealthy food replaces very unhealthy food, that is a win. I don’t have a general index of the healthiness of foods, but in the particular direction of being fattening, let me take the insulin index as a reasonably good measure of how fattening a particular food is. Then this idea can be made very concrete. Eating more lentils that have an insulin index of 42 is a big improvement in relation to weight loss if those lentils are replacing potatoes, which have an insulin index of 88; but if lentils are displacing walnuts that have an insulin index of about 5, that substitution of lentils for walnuts may be a fattening change. Similarly, substituting eating whole fruit instead of candy or cake or fruit juice is a huge improvement. But acting as if eating three peach-sized pieces of fruit is as healthy as eating a similar quantity of green leafy vegetables is a mistake.

To put a point on it: whenever people cite evidence about how healthy a particular type of food is, one always needs to ask “Eaten instead of what?” Even extremely good evidence that a particular type of food is an improvement on the typical American diet does not mean that type of food isn’t problematic in ways that could be avoided by eating something even healthier.

The big problem in Michael Gregor’s attack on Steven Gundry in the video shown just above is Michael Greger’s uncritical acceptance of evidence that a certain type of food is a big improvement on what it replaces in the typical American diet as if it were evidence that food was “healthy” full stop. (That is also the big problem with Joel Kahn’s blog post “The Plant Paradox and The Oxygen Paradox: Don’t Hold Your Breath for Health” and Toby Amidor’s blog post “Ask the Expert: Clearing Up Lectin Misconceptions.”)

The other problem with this video is that Steven Gundry is not, in the end, anti-bean and anti-lentil. He simply says that they need to be cooked carefully—he recommends presoaking and pressure-cooking—in order to destroy as many of the lectins as possible. Presoaking is not at all an unusual type of preparation for beans and lentils. Some people claim that regular cooking is adequate without pressure-cooking. That is indeed a dispute, but not a huge dispute.

Steven Gundry takes his view that animal protein is problematic from T. Colin Campbell and Thomas Campbell, as I do. (See “Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?” and “How Sugar, Too Much Protein, Inflammation and Injury Could Drive Epigenetic Cellular Evolution Toward Cancer.”) But the Campbells do not seem to realize that Steven Gundry is an ally. As strong proponents of a vegan diet, the Campbells seem to be concerned that by recommending some plant foods over others, Steven is unduly limiting the range of options for a vegan diet. They also are concerned that Steven Gundry allows animal foods in moderation in his recommendations.

The most useful aspect of the Campbell’s article shown above is that it details how inappropriate Steven Gundry is with his citations. The citations often are to low-quality sources or to sources that don’t back up what Steven Gundry is saying at all. The Campbells are especially convincing that Steven Gundry is not completely trustworthy in what he says. This of course does not make Steven Gundry’s hypotheses bad hypotheses. It does mean that Steven Gundry can’t be trusted to give us the information to carefully evaluate the limited evidence so far on whether those hypotheses are true or not.

The most interesting thing about “larkasaur’s” review of The Plant Paradox shown just above is his nice discussion of the evidence for anticancer properties of lectins. Larkasaur writes:

Some lectins have anti-cancer properties - but at the same time, this means they are powerful substances that might also cause harm, as Dr. Gundry proposes.

Indeed, a hole in Steven Gundry’s argument that natural insecticides might be hard on cells is that they might be even harder on cancer cells in a way that made them a very mild, and relatively safe type of preventive “chemotherapy.” Of course, I think that fasting is a much better way to go for a likely effective, mild and safe form of preventive “chemotherapy.” My diet and health posts focusing on cancer give a fairly good treatment of this idea:

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

The bottom-line is that if lectins are more harmful to otherwise healthy cells than fasting is, and no harder on cancer than fasting, then fasting rather than lectins is the better way to try to prevent cancer. Of course, if certain lectins work as chemotherapy after someone has already been diagnosed with cancer, that would be great. (See for example this abstract: “Lectins as bioactive plant proteins: a potential in cancer treatment.”) And any anti-cancer effects of lectins have to be weighed in the balance when judging particular foods. Here one would want to know “How hard on cancer?” and “How hard on healthy cells?” for each different type of lectin.

One place where larkasaur powerfully countered one of Steven Gundry’s claims about a specific lectin is this passage, which begins with a quotation from The Plant Paradox, followed by larkasaur’s counter:

The lectin WGA (wheat germ agglutinin) ... can attach to the insulin docking port as if it were the actual insulin molecule, but unlike the real hormone, it never lets go - with devastating results, including reduced muscle mass, starved brain and nerve cells, and plenty of fat.

His reference for this is Effects of wheat germ agglutinin on insulin binding and insulin sensitivity of fat cells. I didn't see the full paper, but from the abstract, this was an in vitro study where WGA actually increased insulin sensitivity at low concentrations, but decreased it at high concentrations. I couldn't find evidence from other studies that the actual blood concentrations of WGA that someone might get from their diet, could affect insulin sensitivity. I did find some evidence that increased intake of whole grains vs refined grains (and whole grains have more WGA) improves insulin sensitivity - e.g. Effect of whole grains on insulin sensitivity in overweight hyperinsulinemic adults. I even found something about wheat germ supplementation alleviating insulin resistance. Wheat germ has a lot more WGA than other wheat products.

Larkasaur also questions some specific claims about Neu5AC and Neu5GC. I was convinced that I should disregard Steven Gundry’s claims about Neu5AC and Neu5GC (which I didn’t pay very much attention to when I read The Plant Paradox in any case).

I really like larkasaur’s discussion of Steven Gundry’s study. Larkasaur writes:

He did a trial on 1000 people, which was presented at an American Heart Assoc. conference. 800 of them had either an autoimmune disease themselves or a family member with an autoimmune disease. They were asked to eat his diet, which "consisted of avoidance of grains, sprouted grains, pseudo-grains, beans and legumes, soy, peanuts, cashews, nightshades, melons and squashes, and non-Southern European cow milk products (Casein A1), and grain and/or bean fed animals.", and adiponectin and TNF-alpha levels were measured every 3 months.

Their levels of TNF-alpha normalized within 6 months, but the adiponectin levels remained elevated.

So he concluded that "TNF-alpha can be used as a marker for gluten/lectin exposure in sensitive individuals."

But he doesn't say how those 1000 people were selected. Maybe they were cherry-picked to show a good result.

And, he didn't have a control group. A control group might consist of people eating his Plant Paradox diet, but also taking a capsule with wheat germ agglutinin (wheat lectin), so that they would be getting the same amount of lectins that people eating the average American diet do. And there would also be a test group, of people eating his Plant Paradox diet and taking a capsule with placebo. That would test whether WGA actually has the effects that he thinks it does.

In addition to dismissing the dangers of A-1 milk to quickly, Larkasaur is too trusting of the official recommendations about the daily requirement for Vitamin D. On that, see

Michael Matthews has a strongly worded title to his long post: “Dr. Gundry’s Plant Paradox Debunked: 7 Science-Based Reasons It’s a Scam.” Here are his Michael’s “7 Science-Based Reasons It’s a Scame”:

The healthiest people in the world eat a lot of lectins.

There’s no real scientific debate about the nutritional value of fruits and vegetables.

Lectins don’t make you fat, overeating does.

Lectins don’t give you heart disease.

Lectins don’t cause “leaky gut” unless you have celiac disease.

Humans have been eating lectins a very, very long time.

Cooking lectins nullifies any potential negative side effects.

1 and 2 are subject to my point above that a food can be demonstrably better than the typical American diet or other typical modern diet, but still have problematic elements. 1 and 6 are subject to the point that Steven Gundry is not claiming that all lectins are harmful, but only that lectins we have not had adequate evolutionary time to adapt to are harmful (though Steven Gundry may be somewhat inconsistent in realizing that this is the position he has to be taking given his logic). On 3, the Michael saying that “overeating makes you fat” leaves unanswered the key question: “What makes you overeat?” Steven Gundry is trying to answer the question of “What makes you overeat?” Anyone who thinks the answer to the question “What makes you overeat?” is either uninteresting or obvious is misguided given where we are in the science. As for 4 and 5, at least in his section headings, Michael is treating “unproven” as the same as “proven false.” No! These are important hypotheses that we don’t have adequate evidence on either way. Finally, on 7, Michael might be right. This is the debate I mentioned earlier about whether pressure-cooking is necessary to destroy most lectins, as Steven Gundry says, or whether regular cooking is enough. As a minor cavil, I do think that Michael Matthews uses the word “nullify” inappropriately about the effect of soaking in reducing lectins by 50%. But the following passage as a whole is useful:

According to a study conducted by scientists at the University of Sao Paulo, boiling beans and other lectin-containing foods for 15 minutes is enough to eliminate almost all of the lectin content. If you use a pressure cooker you can achieve the same effect in just 7.5 minutes, but the end result is the same.

As the scientists put it, “In relation to lectins, there seems to be no residual activity left in properly processed legumes.”

Soaking is another effective method for nullifying lectins. In a study conducted by scientists at Michigan State University, soaking red kidney beans for 12 hours reduced the lectin content by 50%.

Fruit, Nightshades and Other Vegetables with Seeds

Overall, while I think fruit should be eaten in moderation, I think Steven Gundry’s views are too negative about fruit. Many types of fruit are relative high on the insulin index. But I doubt the lectins in fruits are a particular problem. Hence, in relation to fruit, let me recommend that you stick with what I said about fruit in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” and ignore what Steven Gundry says about fruit. I am a little torn about whether or not it is OK to eat the skin, which Steven Gundry advises against.

Other than the nightshades, such as tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and eggplant, the same principles should apply to the botanical fruits that we usually call vegetables, such as cucumbers—except that eating the seeds (or the skin) might be a problem.

On the nightshades, Steven Gundry recommends that they be deskinned, deseeded and pressure cooked. This may be reasonably close to the way many tomato products are made. Because I love fresh tomatoes, I have tried to research whether there is strong positive evidence that they are healthy that could overturn Steven Gundry’s claims that they are problematic. But what I have found is that the bulk of the evidence in nutritional trials about tomatoes is about tomato products that have been processed in the sorts of ways Steven Gundry recommends.

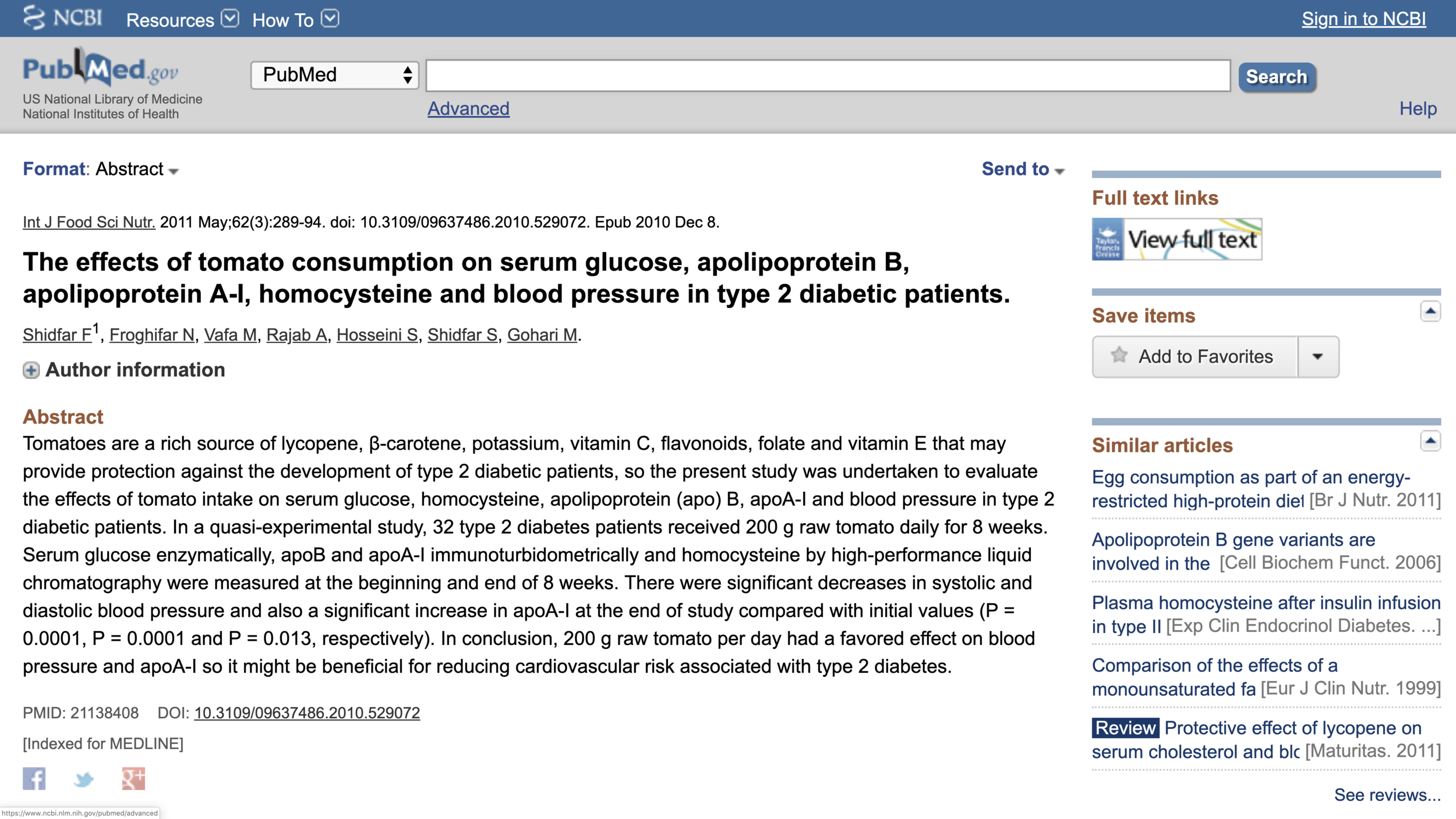

Looking for evidence about the dietary effects of fresh tomatoes, I did find a set of references in the article shown above: “Whole Food versus Supplement: Comparing the Clinical Evidence of Tomato Intake and Lycopene Supplementation on Cardiovascular Risk Factors.”

Here are abstracts for four articles involving fresh tomatoes:

My summary of these abstracts is that while tomato products might reduce inflammation, whole tomatoes are neutral for inflammation, which one might imagine was due to an inflammation-reducing effect of the rest of the tomato (at least when cooked) combined with inflammation-increasing effects of the skin and seeds. But there is some evidence that whole tomatoes seem to reduce blood pressure, raise good cholesterol and reduce oxidative damage. So, overall, fresh tomatoes sound good overall, though skinned, deseeded, cooked tomatoes might be better. The big question I have about these studies are whether those benefits are only when tomatoes are added to a typical American diet (likely displacing some very bad foods), or whether those benefits would be there for me given the diet I am starting from (which currently doesn’t include any fresh tomatoes).

Sometime I should try to do similar kind of online searching for research about eggplant and peppers. (As I mentioned above, I don’t feel I need to do more research about potatoes because they are so high on the insulin index, I am confident they are best avoided.)

Some Favorable Evidence for Steven Gundry’s Claims

On the basic idea that lectins are powerful in their effects on humans, take a look at this abstract:

Finally, here is a post that is relatively supportive of Steven Gundry’s claims:

Here are some of John O’Connors grades for Steven Gundry claims, along with quotations from some of the associated text:

Altered gut microbiome drives lectin sensitivity: C+

Add to the list of medications we take the presence of toxic chemicals in everything from cookware to mattresses, and the rise of GMO crops sprayed with known carcinogens like glyphosate, it’s not unreasonable to assume some people might not be equipped with the microbes to properly digest certain lectins. Lectins are controversial, but increased pollution, prescription medications and widespread use of antibiotics seems to be changing the shape of our microbiomes. In his paper, Do Dietary Lectins Cause Disease, allergist David L.J. Freed theorizes that a serious infection could be the triggering event that alters the microbiome in such a way that we become prone to lectin sensitivity and certain autoimmune conditions.

The altered microbiome theory is gaining traction as consensus fact, and it’s imbalances of the gut that drive Gundry’s claims about lectin. Some have cast him as an outsider, but he’s right in the mainstream of functional medicine. He argues that many people are so used to low levels of inflammation caused by lectin that a state of reduced performance is their “new normal.” But even assuming that a large percentage of the population thrives on lectin, that doesn’t mean we all do.

For example, could a C-section birth, which is thought to be deprive babies of important foundational microbes, combined with a serious infection and a few rounds of broad spectrum antibiotics be just what the doctor ordered for a problem with digesting lectins down the road?

Lectins travel to distant organs: B-

There is even some evidence that lectins can travel to the brain. This study is footnote #5 in the Plant Paradox, and it demonstrates (albeit in a worm model) that lectins can travel from the gut to the brain by way of the Vagus nerve where they impact the function of neurons, offering an alternative theory on the cause and development of Parkinson’s disease.

Again, the study cited by Gundry is a worm model, and it’s on the frontier of nutrition science, but nonetheless, there are other papers that show benefits to mental health when removing grains, so it’s something to experiment with and keep in mind when testing out theories behind anxiety for example. This Danish study showed a 40% reduction in Parkinson’s disease in people who had their Vagus nerve removed.

Lectins and heart disease: C

Peanut oil is high in lectin. In a study titled “Lectin may contribute to the atherogenicity of peanut oil,” researchers found that when lectin was reduced in peanut oil by washing, incidence of heart disease dropped significantly in animal models (mice, rabbits and primates).

Lectins can break down the gut wall: A

Wheat proteins do us harm by attacking the gut lining, making the barrier between our intestines and the inside of the body more permeable, which for some, can lead to symptoms ranging from digestive issues to achy joints to problems with mental health. (R) Zonulin, a protein which can break apart the “intracellular tight junctions” of the gut wall, is produced when we eat wheat. The theory of leaky gut is that the resulting intestinal permeability lets all sorts of bad guys into our blood stream and the immune system goes wild as a result. (R) One of the most successful dietary interventions used to treat Rheumatoid Arthritis is a gluten free Vegan/Vegetarian diet. Of note: some of these RA diet studies have found an “association between disease activity and intestinal flora indicating impact of diet on disease progression.”

Conclusion

Steven Gundry’s hypotheses should be taken very seriously. Both Steven Gundry himself and other researchers should take them as important claims to be proven or disproven by solid evidence. In the meantime, eating low on the insulin index is likely to get you most of the benefits of the Gundry diet. But if you have any chronic autoimmune or other inflammatory reactions, my recommendation is that it would be worth your while to try to follow the full Gundry yes and no list of foods, see if it helps, and if it does, only reintroduce foods you have subtracted one at a time so you can see if some particular food is a problem for you.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

For example, here is what the first section looks like:

I. The Basics