The Four Food Groups Revisited

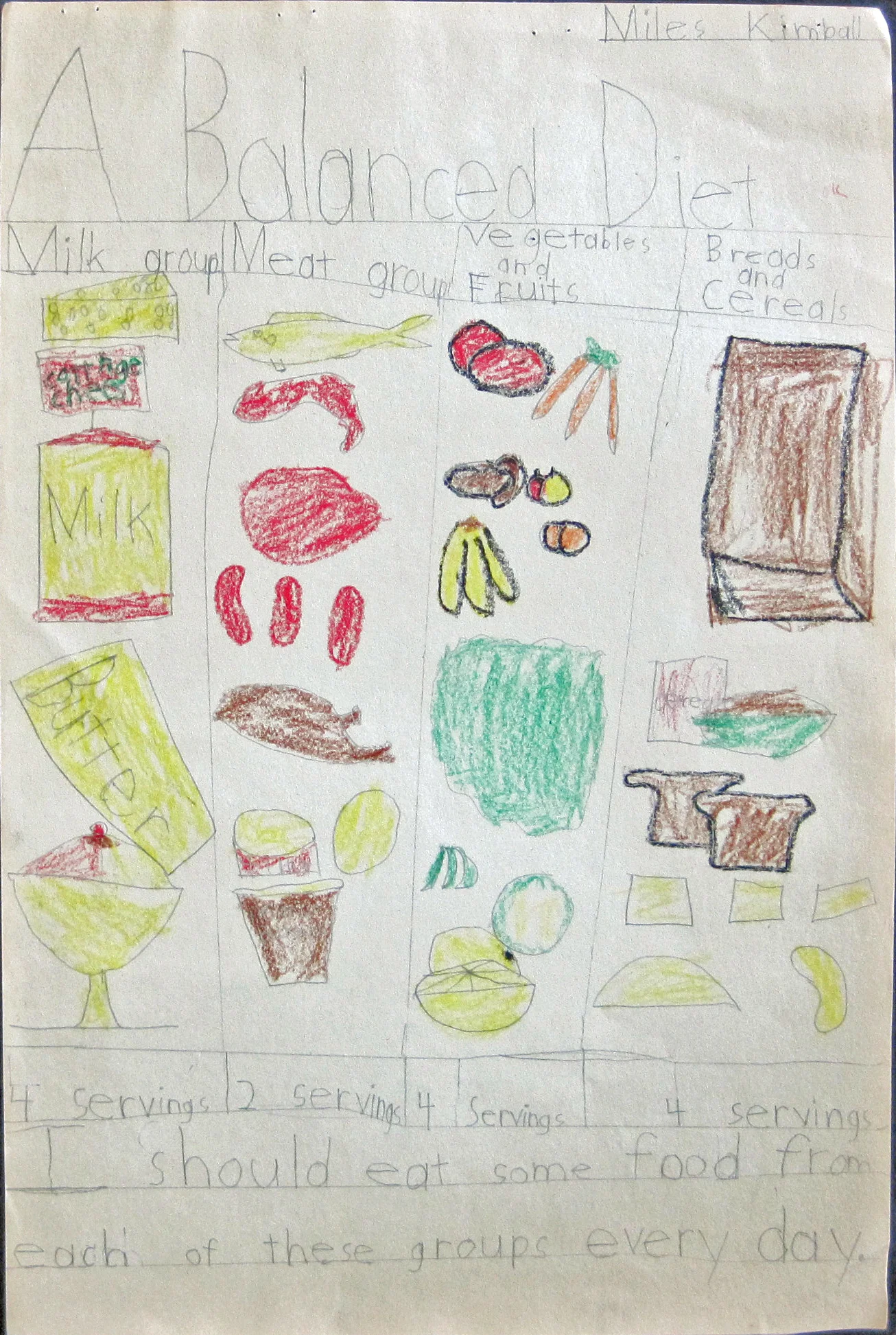

Image created by Miles Spencer Kimball. I hereby give permission to use this image for anything whatsoever, as long as that use includes a link to this blog. In this blog post I question my assertion of half a century ago that what is depicted above makes for a good diet.

In elementary school, back in the 1960’s, I drew illustration of what were then called “The Four Food Groups” as a school assignment. Historically, the formulation of the recommendations to eat a substantial amount from each food group each day may have owed as much to agricultural and broader food business lobbying as to nutrition science. But those recommendations were not as much at variance with reasonably informed nutritional views back then as they are to reasonably informed nutritional views now. Let me give you my view on these four food groups.

Milk Group

I consume quite a bit of milk and cheese, but only because I love dairy. I think of milk and cheese as being somewhat unhealthy. There are two issues. One is the issue that animal protein might be especially good fuel for cancer cells. I wrote about that in these posts:

The other is that the majority of milk sold is from cows with a mutation that makes a structurally weak protein from which a truly nasty 7-amino-acid peptide breaks off. Fortunately, that issue can be largely avoided by eating goat and sheep cheese rather than cow cheese and by drinking A2 milk (which I just saw at Costco yesterday; I have seen it for a while at Whole Foods and, in my area, at Safeway). I wrote about that in these posts:

If you do consume milk, I have some advice here to drink whole milk. (100 calories worth of whole milk will be more satiating than 100 calories of skim milk.)

As for cream and butter, since they have relatively little milk protein, and are quite satiating, I think of them as being some of the healthiest dairy products, though their calories do count in these circumstances:

To preview what I will say again below, in bread and butter, it is the bread that is unhealthy, not the butter. And, in the extreme, eating butter straight is a lot better than the many ways we find to almost eat sugar straight. Eating sugar will make you want more and more and more. At least eating butter straight is self-limiting because butter is relatively satiating.

Meat Group

Meat has the same problem milk does: animal protein typically being abundant in amino acids such as glycine that are especially easy for even metabolically damaged cancer cells to burn as fuel.

Also, because of the protein content, many types of meat ramp up insulin somewhat, as you can see from the tables in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.” David Ludwig points out that meat often also raises glucagon, which is a little like an anti-insulin hormone, but in my own experience, eating beef, for example, tends to leave me somewhat hungry afterwards, which is consistent with the insulin effect being significantly stronger. (Of course, since almost all the meat I eat is at restaurant meals once—or occasionally twice—a week, it might be something else stimulating my insulin than just the meat.)

I do regularly put one egg in “My Giant Salad.” That at least doesn’t ramp up my insulin levels too much. For why that matters, see “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon.” However, the reason I don’t put in two eggs is that I am worried about too much animal protein.

Sometimes nuts are included in the meat group. I view true nuts as very healthy—an ideal snack on the go if you are within your eating window. See “Our Delusions about 'Healthy' Snacks—Nuts to That!”

I haven’t made up my mind about beans—which are also sometimes included in the meat group. They are often medium high on the insulin index, just as beef is. And there are worries based on Steven Gundry’s hypotheses about we and our microbiome not being fully adapted to new world food. See:

As the Wikipedia article “Beans” currently says:

Most of the kinds commonly eaten fresh or dried, those of the genus Phaseolus, come originally from the Americas, being first seen by a European when Christopher Columbus, during his exploration of what may have been the Bahamas, found them growing in fields.

Fruit and Vegetable Group

Nutritionally, the fruit and vegetable group is really at least five very different types of food:

1. Vegetables with easily digested starches: Think potatoes here. Avoid them like the nutritional plague they are. Easily-digested starches turn into sugar quite readily. Also think of peas—and if you count it as a vegetable rather than as a quasi-grain.

2. Vegetables with resistant starch: A reasonable amount of these is OK. I am thinking of green bananas and sweet potatoes. (Beans I discussed above.)

3. Nonstarchy vegetables: Very healthy. Here is a list of nonstarchy vegetables from Wikipedia:

Alfalfa sprouts

Beans (green, Italian, yellow or wax)

Greens (beet or collard greens, dandelion, kale, mustard, turnip)

4. Botanical fruits: Tomatoes and cucumbers, eggplant, squash and zucchini are botanically fruits that we call vegetables for culinary purposes. Many of these botanical fruits that we eat are new world foods that Steven Gundry’s worrisome hypotheses about our inadequate adaptation to New World foods would apply to. So I try to eat these only sparingly. However, as I write in “Reexamining Steve Gundry's `The Plant Paradox’, the evidence for tomatoes—though, perhaps strangely to you, more positive for cooked tomatoes than raw tomatoes—is so positive it is probably good to continue eating them freely.

On both identifying botanical fruits and identifying good vegetables with resistant starches, Steven Gundry’s lists of good and bad foods according to his lights (which include other particular slants he has on things as well) are quite helpful. You might want to take a more positive attitude toward botanical fruits than Steven Gundry, but it is good to know which vegetables are really botanical fruits to see if you notice any reaction when you eat them. A lot of the clinical experience on which Steven Gundry bases his advice is experience with patients who have autoimmune problems, so I would advise adhering to Steven Gundry’s theories more closely if you have autoimmune problems. It is a worthy experiment, in which you are exactly the relevant guinea pig.

5. True fruits: For true fruits, the problem is that sugar is still sugar, even if it is the fructose in fruit that would be extremely healthy if only it were sugar-free. Because of their sugar content, true fruits should be eaten only sparingly. I discuss “The Conundrum of Fruit” in a section of “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”

The bottom line is that even vegetables and fruit—which have gotten a very good reputation—have both good and bad and borderline foods among them.

Breads and Cereals

Avoid this group. Just look at the tables in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” and “Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index.” Also, as an additional mark against ready-to-eat breakfast cereal, see what I say in “The Problem with Processed Food.” Cutting out sugar and foods in this category, along with starchy vegetables, is the key first step to weight loss and better health. On that see:

If you avoid all processed foods made with grains and avoid corn and rice (including brown rice), there may be some other whole grains that are OK. Based on the insulin kicks indicated in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid,” I consider steel-cut plain oatmeal as one of the best whole foods to risk, and the only one I trust that is a reasonably common food in the US.

There is substantial debate here. Some experts are more positive about whole grains. But, given the current state of the evidence, I think it is much safer to lean toward the nonstarchy vegetables that almost all experts think are quite healthy (if one leaves aside the botanical fruits).

Ideas Missing from the ‘Four Food Groups’ Advice

Some key bits of advice are simply missing from the discussion of the four food groups. For example, there is fairly wide agreement that high quality olive oil is quite healthy. It goes well with nonstarchy vegetables! Many people like their olive oil with a little vinegar in it, which is good too.

The biggest idea missing from the ‘Four Food Groups’ advice is that evidence is rolling in that when you eat is, if anything, even more important than what you eat for good health. If you are an adult in good health and not pregnant, you should try to restrict your eating to no more than an 8-hour eating window each day. (That probably means skipping breakfast, which is just as well, since most of the typical American breakfast foods these days are quite unhealthy.) But you can ease into that by working first at getting things down to a 12-hour eating window. We simply aren’t designed to have food all the time; that was a pretty rare situation for our distant ancestors. Our bodies need substantial breaks from food in order to refurbish everything. Here are just a few of my posts on that:

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see: