Increasing Returns to Duration in Fasting

I am in the middle of my annual anti-cancer fast. (See “My Annual Anti-Cancer Fast.”) That has led me to think about returns to scale—in this case, returns to duration—in fasting.

Cautions about Fasting.

Before I dive into the technical details, let me repeat some cautions about fasting. I am not going to get into any trouble for telling people to cut out added sugar from their diet, but there are some legitimate worries about fasting. Here are my cautions in “Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia”:

If your body-mass-index is below 18.5, quit fasting! Here is a link to a BMI calculator.

Definitely people should not do fasting for more than 48 hours without first reading Jason Fung’s two books The Obesity Code (see “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon” and “Five Books That Have Changed My Life”) and The Complete Guide to Fasting.

Those under 20, pregnant or seriously ill should indeed consult a doctor before trying to do any big amount of fasting.

Those on medication need to consult their doctor before doing much fasting. My personal nightmare as someone recommending fasting is that a reader who is already under the care of a doctor who is prescribing medicine might fail to consult their doctor about adjusting the dosage of that medicine in view of the fasting they are doing. Please, please, please, if you want to try fasting and are on medication, you must tell your doctor. That may involve the burden of educating your doctor about fasting. But it could save your life from a medication overdose.

Those who find fasting extremely difficult should not do lengthy fasts.

But, quoting again from “4 Propositions on Weight Loss”: “For healthy, nonpregnant, nonanorexic adults who find it relatively easy, fasting for up to 48 hours is not dangerous—as long as the dosage of any medication they are taking is adjusted for the fact that they are fasting.”

Let me add to these cautions: If you read The Complete Guide to Fasting you will learn that fasting more than two weeks (which I have never done and never intend to do) can lead to discomfort in readjusting to eating food when the fast is over. Also, for extended fasts, you need to take in some minerals/electrolytes. If not, you might get some muscle cramps. These are not that dangerous but are very unpleasant. What I do is simply take one SaltStick capsule each day.

Health Benefits of Fasting.

That said, appropriate fasting is a very powerful boost to health. See for example,

Let me be clear that I am talking about fasting by not eating food, but continuing to drink water (or tea or coffee without sugar). I haven’t come across any claim of a health benefit from not drinking water during fasting, as is urged for religious reasons in both Islamic and Mormon fasting. And there are many reasons to think that drinking a lot of water is good for health.

Fasting is also the central element in losing weight and keeping it off. I have often emphasized the importance of eating a low-insulin-index diet; the most important reason to eat a low-insulin-index diet is that it makes fasting easier. Indeed a famous experiment during World War II involved feeding conscientious objectors a small amount of calories overall in a couple of meals a day that were high on the insulin index. This caused enormous suffering. Don’t do this! In my experience, it is much easier to eat nothing than to eat a few high-insulin-index calories a day. The current top six posts in my bibliographic post “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide” are clear about the importance of fasting:

Also, there is reason to think fasting can prevent cancer:

Increasing Returns to Duration in Fasting.

People differ in their tolerance for fasting. In “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” I talk in some detail about how to do a modified fast. Everything I say here about returns to duration applies to modified fasts as well as more complete fasts. The main difference is that a modified fast has a higher number of calories consumed than in a complete fast, which has zero calories consumed. While calories in/calories out thinking is quite unhelpful to people making incremental changes to the typical American diet, when your insulin level is as low as it is during an extended fast or a modified fast, calories in/calories out thinking is a better guide. (See “Maintaining Weight Loss” and “How Low Insulin Opens a Way to Escape Dieting Hell.)

The reason I think fasting should have increasing returns to duration is all about glycogen. Glycogen is an energy-storage molecule in your muscles and liver. It is the quick-in, quick-out energy storage molecule, while body fat is slow-in, slow-out energy storage. In the first day or two of fasting, much of the energy you need will be drawn from your glycogen stores. It is only as your glycogen stores are run down that the majority of the energy you need will be drawn from your body fat.

Moreover, based on my own experience, I theorize that when you end your fast and resume eating, you will have an enhanced appetite in order to replenish your glycogen stores. By contrast, I think of the amount of body fat having a weaker effect on appetite. (Though likely weaker, it is an important effect. See “Kevin D. Hall and Juen Guo: Why it is so Hard to Lose Weight and so Hard to Keep it Off.”)

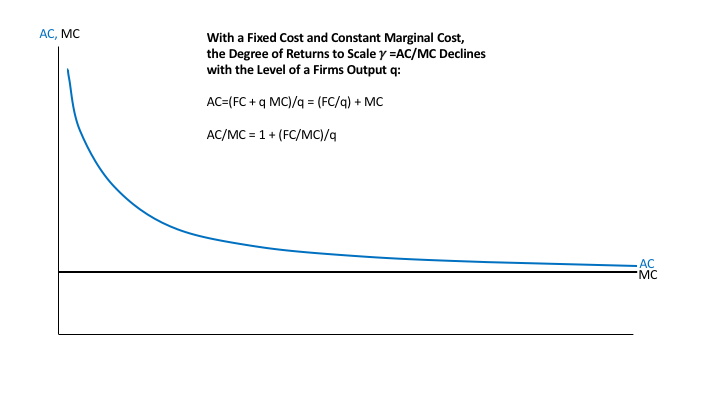

The bottom line of this view is that, for weight loss or maintenance of weight loss, the time it takes to deplete glycogen by fasting is like a fixed cost. Then, after the first couple of days, you should be able to burn something like .6 pounds of body fat per day while fasting. I got that figure from approximating the number of calories in a pound of body fat by 3600, and assuming 2160 pounds burned per day because those who regularly fast get an efficient metabolism (which I think has good anti-cancer properties). This online article says that the average American woman and man, who likely have relatively inefficient metabolisms, burn respectively 2400 and 3100 calories per day.

The “fixed cost” of glycogen burning that substitutes at the beginning for body-fat burning may not literally happen all at the beginning. There is probably some fat-burning early on, but every calorie drawn from glycogen burning isn’t drawn from fat burning, so fat burned in the first couple of days is less than it is during later days. After a few days, glycogen reserves will be gone so that all calories will have to come from fat burning. The theory I am propounding is that the glycogen reserves will bounce back fast when you resume eating, but that body-fat burned will be a relatively long-lasting effect.

When your body is primarily burning fat rather than glycogen, you are said to be in a state of “ketosis.” Those on “keto” diets try to get to fat burning faster by eating so few carbs and so much dietary fat that it is hard for their bodies to replenish glycogen stores—which replenish most easily from carbs. To me, keto diets are a little extreme on what you eat. I would rather eat a wider variety of foods and rely on fasting to get me into ketosis.

Let me say a little more about “keto.” First, many “keto” products are very useful products for those on a low-insulin-index diet. And in terms of explaining what you are doing, “keto” may communicate a reasonably approximation to people who don’t know the term “low-insulin-index diet.” Of course there are people who don’t know “keto” either. For them, “lowcarb” has to do, despite all of its inaccuracy. I have this pair of blog posts comparing a low-insulin-index diet (which is what I recommend to complement fasting), a keto diet and a lowcarb diet:

The bottom line of this post is that, for those who can tolerate either fasting or modified fasting, fasting is a magic bullet for weight loss. (If you want a wonkish discussion of this, see “Magic Bullets vs. Multifaceted Interventions for Economic Stimulus, Economic Development and Weight Loss.”)

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see: