Q: Has the financial crisis prompted a renewed interest in debating and challenging the economic orthodoxy of the “Great Moderation”?

A: The blogosphere was there before the crisis and was helping that conversation to grow, but the crisis certainly brought more people in. Indeed Scott Sumner said on his blog that he was motivated to start blogging because of the crisis. I think people are thinking about a wider range of things.

There are always fashions in economic research, but perhaps not surprisingly there’s more time being devoted to looking at what was going on. People have been working on models where having collateral matters, for example, which show that when the value of houses goes down it’s harder to borrow and lend.

Q: Have the events of the past few years changed the way that you think about policy responses to a crisis?

A: The Great Depression and the Japanese “Lost Decade” certainly made me think about issues surrounding the zero lower bound a lot. It’s true that I wasn’t thinking about the idea of electronic money and negative nominal rates at the time, although I had seen a piece by Greg Mankiw in which he toys with the idea of getting rid of the zero lower bound.

So I was thinking about quantitative easing but then I shifted to thinking about new ideas. It’s too bad that people are simply taking the zero lower bound as a given. I think it will be a hugely important discussion to get people to realise that it’s not some law of nature, it’s an artefact of our paper currency policy.

Q: Some people might consider moving to a world in which we had negative nominal interest rates rather uncharted territory compared with more traditional stimulatory policies such as increasing government spending. Do you think there is a role for more conventional policy moves to pull economies out of a slump?

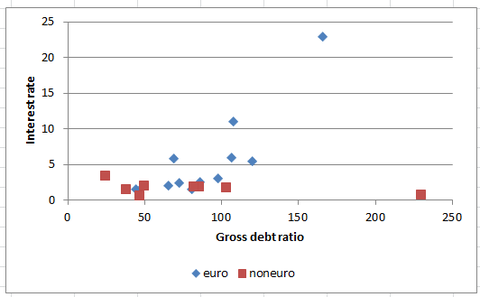

A: As Reinhart. Reinhart and Rogoff have said, national debt above 90% of GDP has a negative impact. Obviously that’s just a stylised fact just like the fact that you tend to have a long-lasting slump after a financial crisis but I think it’s fairly proven that there are problems with having the national debt at too high a level.

Although you could say that stimulating the economy by massive fiscal stimulus is better understood, some of what we understand is that that has downsides in terms of national debt. Being well understood doesn’t always mean that it’s a better policy.

I would say in that context the conservative policy would be national lines of credit. It is something that is in the range where we understand what it would do, although there is some debate over just how much stimulus it would provide. My guess is that it would have a similar impact on demand as handing people that amount of money.

Policies such as bringing forward already planned government spending would also be a quite conservative option. You could, for example, accelerate the restocking of certain types of military equipment that you know you are going to have to buy later anyway.

As soon as you’re doing types of government spending that you wouldn’t be doing otherwise then that’s a fairly long-term addition to the national debt with probably pretty serious negative consequences.

Q: Are you worried about possible unintended consequences of negative nominal interest rates and electronic money?

A: It depends really on how much you believe in monetary neutrality and monetary superneutrality.

If you believe in approximate monetary neutrality then we’ve already seen negative rates before. It is just low real interest rates. It’s only untried if you think that nominal illusion is important.

I have no doubt that it could be confusing to people at first but the main thing we know is that it would mark a return to the type of effective monetary policy that gave us the “Great Moderation”. If you take away the zero lower bound then monetary policy can keep the economy on target and you get the separation between fiscal policy and keeping the economy at its natural level of output.

That is very helpful in terms of the political economy as it’s a wholly different debate to how much you want to redistribute and how you value different kinds of government spending. It becomes very difficult when you try to mix those things up with trying to keep output at its natural level.

Q: What do you make of the argument that there is a case for raising interest rates in a downturn in order to raise inflation expectations and improve confidence in the economy, as some have suggested?

A: I think that’s a huge mistake. It’s a theoretical error that comes from the fact that people are so used to defining and modelling equilibria that they don’t realise that each of these models has to have a story outside the model for how you got to equilibrium.

As far as I know that’s true without exception. Yet we don’t talk enough about the story outside the model. The reason for this is that it can’t be formalised in the same way.

When people don’t think about how you get to an equilibrium they come to conclusions that are just wrong.

In the real world raising rates would be very contractionary. You can have a model in which there are multiple equilibria but I’m pretty sure that raising rates is not the way to move from the equilibrium we’re in to a better one. I can’t imagine the expectations of people in the real world being such that they would see the Federal Reserve or the Bank of Japan raising rates and think that the economy is suddenly going to do great.

Even if it’s theoretically possible, it would only be one of the possibilities. In terms of way that people like John Taylor have been arguing this point, it seems as though he believes rates should go up and is looking for any reasons that could support this conclusion even if they don’t all come from the same theory.

Q: Does any of your current work touch on this subject?

A: Bob Barsky, Rudi Bachmann and I have a paper in progress that’s related to this. Here’s the model that I’ve worked with a lot, which Bob Barsky also got excited about, and then we recruited Rudi:

Let’s simplify it by leaving aside Q-theory and having no adjustment cost for investment. Now I have a delay condition for investment that says “I want to accelerate investment if the net rental rate is greater than the interest rate”.

So I have a graph of output on the horizontal axis and on the vertical axis I’ve got the net rental rate and the real interest rate. I have a net rental rate curve, which we call a KE curve because I think Sargent called it that. There’s no mystery that the rental rate goes up with output. When the economy is booming you’re going to be more eager to rent some capital by leasing office space or rent some

machines.

The other curve is a monetary policy rule. When I think in continuous time, the number one thing I need for the stability of monetary policy is for it to be steeperthan the net rental rate. However, you’ve got a problem when you get down to the zero lower bound as it’s tough to keep interest rates steeper than rental rates. So you can easily get multiple equilibria.

If you have zero gross investment, that would be a low level of output. Suppose that level of output gives you a net rental rate below zero. That would be an example of a stable equilibrium with zero gross investment. If you did nothing eventually the capital stock would deplete to the point where the net rental rate would come above zero and the economy would restart, but that could be an awfully long slump.

The other thing that can happen is that you have some fiscal stimulus that could get you past the unstable equilibrium in the middle and you could jump up to the good equilibrium again. The very existence of the good equilibrium depends upon monetary policy so you might need a combination of monetary and fiscal policy.

Yet you can get out of it just through monetary policy. If you don’t have a zero lower bound then you can keep cutting the interest rate until it does get past the net rental rate. Moreover, you wouldn’t have fallen into the bad equilibrium in the first place if you had electronic money and no zero lower bound.

What I think is happening in people’s thinking is that they have observed that you have higher interest rates during a boom. That, however, is about the net rental rate and not about the monetary policy. In fact, when you have these two upwards-sloping curves it is precisely by cutting interest rates that you achieve higher interest rates as the economy recovers.

It’s theoretically possible that the economy could miraculously jump to the good equilibrium with no impulse whatsoever and that could coincide with a rise in the interest rate. But in terms of causality it’s still the miraculous restoration of confidence that caused the jump, not the higher interest rate.