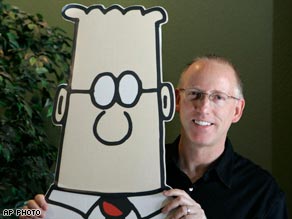

Scott Adams's Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich

Scott Adams with his creation “Dilbert"

With all the pleasure he has given millions with his Dilbert comics and all of his other incisive Wall Street Journal essays, it is a high standard indeed to say that one particular Wall Street Journal essay is Scott Adam’s finest hour, but I think this is it: “How to Tax the Rich.” Let me know in the comments what other wonderful things there are out there by Scott that can vie for the honor of Scott’s finest hour.

Even after allowing for comic license, I think I can say that Scott himself is conscious of the value of his own idea, as can be seen from these two passages:

Whenever I feel as if I’m on a path toward certain doom, which happens every time I pay attention to the news, I like to imagine that some lonely genius will come up with a clever solution to save the world. Imagination is a wonderful thing. I don’t have much control over the big realities, such as the economy, but I’m an expert at programming my own delusions.

Try to imagine that the idea that saves the country is an entirely new one. It’s too much of a stretch to imagine that a stale idea would suddenly become acceptable. In fact, that’s the dividing line between imagination and insanity. Only crazy people imagine that bad ideas can suddenly become good if you keep trying them. So let’s assume that our imagined solution is a brand new idea. That feels less crazy and more optimistic. Another advantage is that no one has an entrenched view about an idea that has never been heard.

For those of you with healthy egos—and that would be every reader of The Wall Street Journal—you can make this fantasy extra delicious by imagining that you are the person who comes up with the idea that saves the world. I’ll show you how to imagine that.

Scott’s overall idea is based on a fundamental fact that Giorgio Primiceri pointed out when I talked to him about taxing the rich at CREI in Barcelona in June: because each dollar is worth less and less the richer one is, a wide variety of other things end up mattering more for rich people than money. (On the principle that each dollar is worth less for the rich than for the poor in interpersonal comparisons, see my post “What is a Supply-Side Liberal?” But the point here is different: here it is about the value of a dollar compared to other things the rich person wants.) One should be careful: sometimes, one of the things that propels someone toward riches is having a greater desire for the things that money can buy than the average person (relative to, say, a desire for leisure time). But still, at some level of riches, the attractions of the things that extra money could directly purchase start to pale in comparison to other things, even for someone who truly loves the things that money can buy.

Scott writes:

If we accept that the rich can be taxed at a different rate than everyone else, we can also imagine that there could be other differences in how the rich are taxed. That’s the part we can tinker with, and that’s where the bad version comes in. In a minute, I’ll float some bad ideas about how the rich can feel good while the rest of society is rifling through their pockets.

I can think of five benefits that the country could offer to the rich in return for higher taxes: time, gratitude, incentives, shared pain and power.

The trouble with our tax system as it stands–and this has nothing to do with its arithmetic–is that instead our tax system does just about everything possible to make paying taxes a horrible, aversive, demeaning experience for the rich, even apart from the money they surrender.

Although few of us make it into the top 1%, my fellow economists and I definitely count among the moderately rich. Certainly folks as rich as we economists are–or as many other highly-paid professionals such as doctors and lawyers are–need to be taxed relatively heavily in order to get enough revenue to fund the government at anything close to its current level. And we are. With the voice of my late colleague Tom Juster in my head reminding me of the joys of helping the poor through paying my taxes, I don’t personally need one, but I find it remarkable that I have yet to receive a thank you note for paying my taxes. When I fill out my taxes, I notice that even receipts for $25 donations have thank you notes attached. But for the tens of thousands of dollars I give each year to help keep our wonderful Republic afloat, nothing. Can’t we do a little more as a nation to honor our taxpayers individually? If the First Spouse is willing, how about a thank-you note for every taxpayer signed by the President of the United States and the often much-more-popular First Spouse? (To save on postage, it could be mailed along with the annual Social Security report people get sometime close to their birthdays, for example.) And how about a dinner at the White House honoring the top 100 taxpayers in the country? Not the 100 richest people in the country, but the top 100 taxpayers. One might object that they would just use the opportunity to lobby for lower taxes, but if they did, they wouldn’t get invited the next year. If we honored the top 100 taxpayers like that, maybe they wouldn’t feel like fools for paying their taxes instead of finding some way to evade them like many of their friends and acquaintances.

A thank you note for every taxpayer and a dinner at the White House honoring the top 100 taxpayers are just two of many possible specific ideas for enlisting the full range of people’s motivations in an effort to make paying taxes something that people won’t try quite as hard to avoid. I promise to work hard to come up with more ideas in future posts, and encourage other bloggers to do the same. In trying to come up with ideas along these lines, I rest easy in the confidence that Scott is covering my flank with much wilder proposals. He explains his approach as follows, picking up after a passage I quoted earlier:

For those of you with healthy egos—and that would be every reader of The Wall Street Journal—you can make this fantasy extra delicious by imagining that you are the person who comes up with the idea that saves the world. I’ll show you how to imagine that.

I think you’ll be surprised at how easy it is. I spent some time working in the television industry, and I learned a technique that writers use. It’s called “the bad version.” When you feel that a plot solution exists, but you can’t yet imagine it, you describe instead a bad version that has no purpose other than stimulating the other writers to imagine a better version.

I’ll leave you to read for yourself the specific ideas Scott proposes in “How to Tax the Rich.” They are sure to inspire each of you with the thought “I can do better than that.”

Standard economic models of taxation (such as the one in my post “The Flat Tax, the Head Tax, and the Size of Government: A Tax Parable”) simplify by focusing only on a small list of desires (say consumption purchased in the market, leisure and public goods). But human beings want many things, including many intangibles. It is my belief that we can do much better at harnessing these other desires for the common good than we have. Once upon a time, many Communists made the mistake of thinking that even for the typical individual other motivations could be made to supersede the desires for the things money can buy. Unfortunately, the only desire they found that was reliably stronger was the desire to avoid being shot, sent to Siberia, or the like. But surely we can construct a better society if we recognize the other desires people have at the strength those desires actually have.

Let me end by giving two routine examples of how much people will do for motivations other than money. First, I once received an email from a professor I had known at Harvard, asking why Kim Clark would step down from his position as Dean of Harvard Business School to take a position as President of Brigham Young University-Idaho (the Mormon Church’s second most important university, coming after the better-known Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah). The question arose because in the normal pecking order of academic leadership positions, President of BYU-Idaho is a big step down from Dean of Harvard Business School, and the move probably reduced Kim Clark’s lifetime earning power significantly. My answer was fairly simple: religious motivations that motivated Kim Clark as a believing Mormon.

Second, although I have already cited it in my post “Copyright,” I love Eli Dourado’s post “Why I Should Blog More” so much, I am going to quote from it here as well. Eli writes:

People still think that the public goods problem is a problem. The naïve view of public goods is often at odds with reality, however. This is especially so when one considers the things we might care most about: our jobs and relationships. In modern society, better jobs and relationships are often the reward for the production of positive externalities. As it turns out, people like to work and socialize with those who create value for others.

This effect is pretty strong. Can you name a person who ended up poor and unhappy because they devoted too many resources to the voluntary production of public goods of actual value to the rest of society? I can’t, at least not off the top of my head.

My standard advice for those few younger people who ask me for it is simply to produce a lot of external value. Don’t worry about being compensated for it right away. If you succeed in producing things that are of value to others, they will want you around, and you will have plenty of rewarding opportunities you would not have had otherwise.

If we could arrange things so that paying taxes to indirectly support public goods could somehow result in the kinds of delayed benefits Eli traces as resulting from directly producing public goods, we wouldn’t have to worry so much about tax distortions.