Magic Ingredient 1: More K-12 School

In my book, the two truly wonderful things Barack has done on the domestic front are advancing gay rights (through ending “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and more recently by rhetorical support for gay marriage rights) and advancing education reform through the brilliant work of Arne Duncan as his Secretary of Education. By dangling a few gigadollars worth of grant money in front of states, Arne has gotten states to fall all over themselves passing education reforms that I would have thought impossible in such a short time–often with buy-in from the teachers unions. I cheer on this effort and other efforts at education reform.

Although I am in favor of more school choice, including both charter schools and Milton Friedman’s still excellent idea of education vouchers, let me focus in on two aspects of education reform that can be fully implemented within regular public schools: increasing the total amount of schooling kids get in their K-12 years and making sure they are legally qualified to pursue a wide range of careers when they earn a high school diploma.

Sometimes the most important fact in a given area is one so obvious it might not even seem worth saying. I heard one such fact from a top researcher in education at an academic seminar at the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center: the single most important variable in predicting whether a student will get a test question right is whether that topic was covered in class or not. Students don’t always remember what they were taught. But they never remember something they weren’t taught. More time in school means more things can be taught at least once, and the more important things can even be repeated a few times.

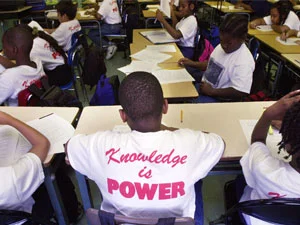

The secret recipe behind the “Knowledge is Power Program” or KIPP schools (which have been very successful even with highly disadvantaged kids) is this:

- They motivate students by convincing them they can succeed and have a better life through working hard in school.

- They keep order, so the students are not distracted from learning.

- They have the students study hard for many long hours, with a long school day, a long school week (some school on Saturdays), and a long school year (school during the Summer).

The KIPP schools also have highly motivated teachers, but that is a topic for another day.

So my first proposal for this post is to go to a 12-month school year, and to extend the school day until at least 5 PM (but with many extracurricular activities and sports being eligible to count as part of the school day, as they do in Japan). Research has shown poor kids and rich kids learn at a somewhat similar rate during the school year, but that poor kids forget a lot during the Summer, while rich kids retain more. So lengthening the school year is especially helpful for poor kids. Lengthening the school year and the school day also effectively provides year-round day care for poor parents who desperately need it. For rich families who are used to being able to go on a summer vacation, I would allow families to make proposals for family or individual activities with educational value that could substitute for some part of school in the summer, and grant permission for these substitutions for summer school relatively liberally for anything that research shows keeps kids academically sharp. The poor kids will think this is unfair, but they simply need the formal schooling more because their parents can’t afford other high-quality educational activities. So keeping them in school during the summer really is doing them a favor.

I won’t try to work out all the details of how the longer school day and school year would work, but I need to address one objection that will spring to many readers minds: extra costs. I don’t want to assume massive new infusions of money into schooling that might never be available. But I think it can be done without major additional costs. The school buildings are there anyway, year round, so the major expense to worry about is teacher salaries. Here I think we could start by having each teacher teach the same number of annual hours as they now do, but staggered throughout the year. (Over time, on a merit basis, some teachers could be allowed to work year round at a commensurately higher salary, to make up for normal attrition.) The margin that would give is that class sizes would go up. Except in Kindergarten, and maybe in 1st grade, higher class sizes have been shown by research to have only a small effect on learning–probably less than a tenth the effect on learning on the minus side that more total school hours for the kids would have on the plus side. We might need to knock out a few walls between classrooms to accommodate these larger class sizes, but it could be done. (Note that the total number of kids in school at any one time would be basically the same as now, so the kids would fit.) Even with these expedients, costs would go up some. For example, the lights would have to be kept on longer. But I think it should be manageable. And the fact that some of the rich kids wouldn’t be there in the summer would either help bring down class sizes for the poor kids then, or allow school districts to save on staffing during the summer.

Much of the extra schooling time from the longer school day and longer school year would go toward learning the basics better–reading, writing, math–and maybe getting a little extra cultural background that will help students enjoy a wider range of things in their lives. But I want to claim some of the extra time to make sure that the kids are legally qualified to do a wide range of jobs when they finish school. One of the most important drifts of political economy at the state level in the United States has been toward requiring licenses for more and more jobs. Here is what Morris Kleiner and Alan Krueger say in their 2008 National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper “The Prevalence and Effect of Occupational Licensing”:

We find that in 2006, 29 percent of the workforce was required to hold an occupational license from a government agency … Our multivariate estimates suggest that licensing has about the same quantitative impact on wages as do unions–that is about 15 percent …

Many economists and other observers feel that occupational licensing has gone too far. Here is an interesting Wall Street Journal article:

Dick Carpenter and Lisa Knepper WSJ “Do Barbers Really Need a License?”

And here is an article from what I think is a Libertarian website (“The Library of Economics and Liberty”):

S David Young, “Occupational Licensing”

Others argue that health and safety and basic competence really do require training even for many jobs that sound easy, such as cutting hair or cutting nails.

What I want to do is to restrain the tendency to go overboard on occupational licensing while allowing genuinely necessary competencies to be transmitted by requiring states to ensure that their schools high school tracks that would make it reasonably possible to be meet the legal qualifications for any of at least 60% of all licensed occupations, with each student able to be qualified with his or her high school diploma for at least 10% of all licensed occupations. Then the graduates might actually be able to get a job. This requirement for getting the Federal education grant could be met by any combination of reducing licensing requirements and increasing effective training that each state chose. I am sure that states would game the rule, so that the overall effect would be less than what this sounds on the surface, but it would be better than the way things are now, where students graduating from high school are kept out of many of the more desirable occupations by occupational licensing restrictions.

Many schools these days have a program that allows more ambitious students to earn an Associate’s degree (equivalent to two years of college) before their time in publicly-funded high school education runs out. For them, I would add the requirement that states make it possible for ambitious students doing the equivalent of an Associate’s degree to be licensed for any of 50% of medical care jobs. (Being a doctor would still require much, much more training. Note: “any” is not the same as “all.” They would have to do some choosing.) This would not only help these students get jobs, it would help us as a nation to be able to afford the medical care that we want.

Note that any reduction in occupational licensing restrictions increases the value of having readily available and accurate quality ratings for services as well as goods. To be honest, in my personal experience, which I think will match that of most of my readers, I have seldom been satisfied with services from the bottom half of those in any occupation. But the stratification into different quality levels should be handled by the market as much as possible (and by government fiat as little as possible), with continually improved web-based ratings mechanisms. High school graduates need entry-level jobs, even though it is hard to be really good at anything at first before accumulating experience, especially for those who would not have been able to get jobs at all without the changes I am advocating.

Let me end by explaining my title. In his recent post “What it to be done now, Jeff Sachs appears to miss the point by a substantial margin,” Brad DeLong lays out his short-run Keynesian program for the economy, and says this about Jeff Sachs’s column:

When I started Jeff’s column, I thought it was going to be an exercise in hippie-punching, along the lines of: “Simplistic Keynesian remedies will not solve our problems. See, I am a Very Serious Person. What will solve our problems is X.” And X would turn out to be simplistic Keynesian remedies plus some magic ingredient Y. That might have been useful. It would have been a call for simplistic Keynesian policies plus magic ingredient Y.

As I discussed in my immediately previous post “Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football” I am all for more aggregate demand right now, as long as it is achieved in ways that don’t ultimately add too much to the national debt, but what Brad DeLong’s words sparked in me was a desire to come up with “magic ingredient Y” for long run growth and improvement in the economy. Thinking that there might be many magic ingredients that can help in the long run–hopefully more than there are letters in the alphabet, I am going to start off with numbers. Hence, “Magic Ingredient 1: More K-12 School.”