Chris Kimball Reacts to 'The Supreme Court Confronts the Principles of Multivariable Calculus in Extending Employment Protections to Gay and Transgender Employees'

My brother Chris is the most frequent contributor of guest posts to my blog. You can see links to the others at the bottom of this post. (Many of these guest posts are about Mormonism.) Chris got a bachelor’s degree in applied math, went to law school, and became a top flight tax lawyer. So I was curious about his reaction to my post “The Supreme Court Confronts the Principles of Multivariable Calculus in Extending Employment Protections to Gay and Transgender Employees.” I thought what he replied to me email query would be of interests to others as well. To understand his comments, read my post “The Supreme Court Confronts the Principles of Multivariable Calculus in Extending Employment Protections to Gay and Transgender Employees” first. Here is what he said:

1. I think the meaning of "sex" in the 1964 Civil Rights Act is a relatively hard question. I'm not satisfied the Supreme Court got it right. Much as I think we should have protection for sex and gender minorities, there is a risk that the Supreme Court is legislating here. The fact that our Congress finds it so difficult to do perfectly reasonable things is not a good excuse for legislation by courts, in my opinion, for the long run.

2. Complexities in but-for analyses are well understood. At least, they were well understood in my law school in the early 1980s. The University of Chicago Law School was at the forefront of law and economics, including applying mathematical concepts to judicial decision making, so I can't really say what the overall market is like. But I do know top litigators. My partners argue these cases before the Supreme Court. They are more than capable of making cogent arguments about coordinate systems, and I remember there is precedent for arguing and understanding the complexities of a but-for analysis.

3. Personally I would like to use the language of calculus and finite differences. However, I think the general state of mathematical literacy is too low for that proposal to get traction. My just barely informed judgment is that there is room for improvement in the way we make and interpret the arguments, including in the language used, but I would not go all the way to the language of calculus and finite differences.

4. I think/I guess/I believe there have been advances in my lifetime and there are more yet to be made, that have the nature of mathematics and probability and decision theory and economics rendered in precise but common English. That's not where I spend my time these days, but I have in the past (writing about the use of option pricing models, for one notable example).

Don’t miss these other guest posts by Chris:

Christian Kimball: Anger [1], Marriage [2], and the Mormon Church [3]

Christian Kimball on the Fallibility of Mormon Leaders and on Gay Marriage

In addition, Chris is my coauthor for

Karl's List of Alleged Scandals in Economics

In order to get one’s priors appropriately calibrated, it is important to know about bad things that people have done. But it is also important to get things right about which specific accusations are really true and which are unfounded.

“Exogeny Karl” defends Economics Job Market Rumors as a useful muckraking site, giving this list of alleged scandals in economics that EJMR helped publicize.

Don’t believe all of these accusations. For example, Claudia Sahm effectively debunks the accusation against her here and here. See also here. This was never a credible allegation.

I’d be glad to hear arguments for or against the truth of any of the other allegations Karl makes.

On Reinhart and Rogoff’s errors, Yichuan Wang and I say our piece in

On other aspects of Economics Job Market Rumors, my blog has these posts:

Open Conspiracies, Exhibit B: Glyphosate

In “Open Conspiracies, Exhibit A: Whitewashing Sugar” I argue that people should worry much more about open conspiracies than “secret conspiracies.” An “open conspiracy” is one for which anyone who is exceptionally diligent can learn all about from public available information, but for which there are big efforts to keep people from knowing about it easily.

There are many reasons to worry about highly processed food. For examples, see:

One more reason to worry about highly processed food is its heavy reliance on grains that are routinely doused with large amounts of pesticides. For example, quoting from “Corporations can legally put carcinogens in our food without warning labels. Here's why” by Matthew Rosza (with bullets added to separate passages):

A recent study by the Environmental Working Group revealed something horrifying: Glyphosate, the active ingredient in the popular weedkiller Roundup, was present in 17 of the 21 oat-based cereal and snack products at levels considered unsafe for children. That includes six different brands of Cheerios, one of the most popular American cereals.

The safe glyphosate limit for children is 160 parts per billion (ppb), yet Honey Nut Cheerios Medley Crunch has 833 parts per billion and regular Cheerios has 729 ppb. While the potential risks of glyphosate are fiercely debated, many scientists believe that it is linked to cancer.

So if there are unsafe levels of glyphosate in a cereal popular with children, why isn't this disclosed on the cereal boxes?

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has labeled glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic” and the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment categorized it as a “chemical known to the state to cause cancer.”

Glyphosate is primarily used on Roundup Ready corn and soybeans that are genetically modified to withstand the toxin. Glyphosate is also sprayed on other non-GMO crops, like wheat, oats, barley and beans, right before harvest.

Monsanto has waged a sophisticated PR campaign to bully scientists and undermine findings that glyphosate is cancerous. In addition Monsanto and agribusiness leaders protecting the company's interests have a revolving door relationship with many agencies that are supposed to be overseeing and regulating the corporation. Monsanto and agribusiness associations have also made significant political contributions to Congressmembers like former Rep Lamar Smith from Texas who chaired the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee …

Matt Rosza also provides a link to the article shown below backing up his claim that Monsanto has worked hard to keep people from realizing the dangers of glyphosate.

Let me quote just one paragraph from Carey Gillam’s “How Monsanto Manufactured ‘Outrage’ at IARC over Cancer Classification”:

Internal company records show not just the level of fear Monsanto had over the impending review, but notably that company officials fully expected IARC scientists would find at least some cancer connections to glyphosate. Company scientists discussed the “vulnerability” that surrounded their efforts to defend glyphosate amid multiple unfavorable research findings in studies of people and animals exposed to the weed killer. In addition to epidemiology studies, “we also have potential vulnerabilities in the other areas that IARC will consider, namely, exposure, genetox and mode of action…” a Monsanto scientist wrote in October 2014. That same email discussed a need to find allies and arrange funding for a “fight”—all months before the IARC meeting in March 2015.

One simple way to avoid most highly processed food and avoid many of these problems is to go off sugar. That entails avoiding most highly processed food, because most of it has quite a bit of sugar. Most foods that are required to have a nutritional label will reveal on that label that sugar is a key ingredient.

There are many other open conspiracies, just in the diet and health area. I write about two other candidates for an open conspiracy in these posts:

When there is a legitimate scientific dispute about dangers like these, the right answer is to devote resources into getting more definitive evidence. But those who are worried their product is dangerous often both (a) say the scientific evidence is inconclusive and (b) do everything in their power (usually behind the scenes) to prevent more conclusive scientific evidence from being put together.

Unfortunately, when a company has an incentive to fuzz up the truth, it often does. And despite growing disclosure requirements, it is still not always obvious when someone with a motivation to fuzz up the truth is behind a particular line of argument.

I am by nature a trusting person, but being a blogger means I come across a lot of information that backs up the idea that many people lie or deceive in public. There is a lot of goodness in humanity, but you can’t depend on everyone to always forward the truth. It can be quite frustrating to try to separate truth from falsehood. I do the best I can within the constraints of the amount of time I spend on each post.

For organized links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The Federalist Papers #37: Why the Constitution Isn't Perfect—And Why No Constitution Could Be. James Madison

“The best is the mortal enemy of the good.” —Montesquieu

Perfectionism can be very destructive. In this blog, see “How Perfectionism Has Made the Pandemic Worse,” “On Perfectionism” and “Gerard Theoret: 3 Turns of the Screw.” In the Federalist Papers #37, James Madison argues against letting perfectionism sink the US Constitution. Many of his arguments are valuable as arguments against perfectionism in other endeavors.

As a guide to James Madison’s argument, let me add headings and notes in bold italics to label the key arguments and non-bold italics to highlight the most interesting passages. (James Madison himself does not use italics in the Federalist Papers #37.)

FEDERALIST NO. 37

Concerning the Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government

From the Daily Advertiser

Friday, January 11, 1788.

Author: James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

IN REVIEWING the defects of the existing Confederation, and showing that they cannot be supplied by a government of less energy than that before the public, several of the most important principles of the latter fell of course under consideration. But as the ultimate object of these papers is to determine clearly and fully the merits of this Constitution, and the expediency of adopting it, our plan cannot be complete without taking a more critical and thorough survey of the work of the convention, without examining it on all its sides, comparing it in all its parts, and calculating its probable effects.

That this remaining task may be executed under impressions conducive to a just and fair result, some reflections must in this place be indulged, which candor previously suggests.

Those who oppose something can usually find fault, weaponizing perfectionism. On the other side proponents can gloss over genuine problems. Good decisions require being open-minded. It is a misfortune, inseparable from human affairs, that public measures are rarely investigated with that spirit of moderation which is essential to a just estimate of their real tendency to advance or obstruct the public good; and that this spirit is more apt to be diminished than promoted, by those occasions which require an unusual exercise of it. To those who have been led by experience to attend to this consideration, it could not appear surprising, that the act of the convention, which recommends so many important changes and innovations, which may be viewed in so many lights and relations, and which touches the springs of so many passions and interests, should find or excite dispositions unfriendly, both on one side and on the other, to a fair discussion and accurate judgment of its merits. In some, it has been too evident from their own publications, that they have scanned the proposed Constitution, not only with a predisposition to censure, but with a predetermination to condemn; as the language held by others betrays an opposite predetermination or bias, which must render their opinions also of little moment in the question. In placing, however, these different characters on a level, with respect to the weight of their opinions, I wish not to insinuate that there may not be a material difference in the purity of their intentions. It is but just to remark in favor of the latter description, that as our situation is universally admitted to be peculiarly critical, and to require indispensably that something should be done for our relief, the predetermined patron of what has been actually done may have taken his bias from the weight of these considerations, as well as from considerations of a sinister nature. The predetermined adversary, on the other hand, can have been governed by no venial motive whatever. The intentions of the first may be upright, as they may on the contrary be culpable. The views of the last cannot be upright, and must be culpable. But the truth is, that these papers are not addressed to persons falling under either of these characters. They solicit the attention of those only, who add to a sincere zeal for the happiness of their country, a temper favorable to a just estimate of the means of promoting it.

Perfection is unattainable … Persons of this character will proceed to an examination of the plan submitted by the convention, not only without a disposition to find or to magnify faults; but will see the propriety of reflecting, that a faultless plan was not to be expected. Nor will they barely make allowances for the errors which may be chargeable on the fallibility to which the convention, as a body of men, were liable; but will keep in mind, that they themselves also are but men, and ought not to assume an infallibility in rejudging the fallible opinions of others. … and judgement of fallible things is itself fallible.

With equal readiness will it be perceived, that besides these inducements to candor, many allowances ought to be made for the difficulties inherent in the very nature of the undertaking referred to the convention.

The Constitutional Convention had historical guidance mainly on what not to do, not on what should be done. The novelty of the undertaking immediately strikes us. It has been shown in the course of these papers, that the existing Confederation is founded on principles which are fallacious; that we must consequently change this first foundation, and with it the superstructure resting upon it. It has been shown, that the other confederacies which could be consulted as precedents have been vitiated by the same erroneous principles, and can therefore furnish no other light than that of beacons, which give warning of the course to be shunned, without pointing out that which ought to be pursued. The most that the convention could do in such a situation, was to avoid the errors suggested by the past experience of other countries, as well as of our own; and to provide a convenient mode of rectifying their own errors, as future experiences may unfold them.

There is a tradeoff between energy and stability of government and liberty. Both are important. Among the difficulties encountered by the convention, a very important one must have lain in combining the requisite stability and energy in government, with the inviolable attention due to liberty and to the republican form. Without substantially accomplishing this part of their undertaking, they would have very imperfectly fulfilled the object of their appointment, or the expectation of the public; yet that it could not be easily accomplished, will be denied by no one who is unwilling to betray his ignorance of the subject. Energy in government is essential to that security against external and internal danger, and to that prompt and salutary execution of the laws which enter into the very definition of good government. Stability in government is essential to national character and to the advantages annexed to it, as well as to that repose and confidence in the minds of the people, which are among the chief blessings of civil society. An irregular and mutable legislation is not more an evil in itself than it is odious to the people; and it may be pronounced with assurance that the people of this country, enlightened as they are with regard to the nature, and interested, as the great body of them are, in the effects of good government, will never be satisfied till some remedy be applied to the vicissitudes and uncertainties which characterize the State administrations. On comparing, however, these valuable ingredients with the vital principles of liberty, we must perceive at once the difficulty of mingling them together in their due proportions. The genius of republican liberty seems to demand on one side, not only that all power should be derived from the people, but that those intrusted with it should be kept in independence on the people, by a short duration of their appointments; and that even during this short period the trust should be placed not in a few, but a number of hands. Stability, on the contrary, requires that the hands in which power is lodged should continue for a length of time the same. A frequent change of men will result from a frequent return of elections; and a frequent change of measures from a frequent change of men: whilst energy in government requires not only a certain duration of power, but the execution of it by a single hand.

How far the convention may have succeeded in this part of their work, will better appear on a more accurate view of it. From the cursory view here taken, it must clearly appear to have been an arduous part.

The appropriate division of power been the federal government and the states is unclear. Not less arduous must have been the task of marking the proper line of partition between the authority of the general and that of the State governments. Natural science often has trouble drawing appropriate division lines. Every man will be sensible of this difficulty, in proportion as he has been accustomed to contemplate and discriminate objects extensive and complicated in their nature. The faculties of the mind itself have never yet been distinguished and defined, with satisfactory precision, by all the efforts of the most acute and metaphysical philosophers. Sense, perception, judgment, desire, volition, memory, imagination, are found to be separated by such delicate shades and minute gradations that their boundaries have eluded the most subtle investigations, and remain a pregnant source of ingenious disquisition and controversy. The boundaries between the great kingdom of nature, and, still more, between the various provinces, and lesser portions, into which they are subdivided, afford another illustration of the same important truth. The most sagacious and laborious naturalists have never yet succeeded in tracing with certainty the line which separates the district of vegetable life from the neighboring region of unorganized matter, or which marks the termination of the former and the commencement of the animal empire. A still greater obscurity lies in the distinctive characters by which the objects in each of these great departments of nature have been arranged and assorted.

It is even harder to draw appropriate division lines in the social sciences—and in particular in political science and law. When we pass from the works of nature, in which all the delineations are perfectly accurate, and appear to be otherwise only from the imperfection of the eye which surveys them, to the institutions of man, in which the obscurity arises as well from the object itself as from the organ by which it is contemplated, we must perceive the necessity of moderating still further our expectations and hopes from the efforts of human sagacity. Experience has instructed us that no skill in the science of government has yet been able to discriminate and define, with sufficient certainty, its three great provinces the legislative, executive, and judiciary; or even the privileges and powers of the different legislative branches. Questions daily occur in the course of practice, which prove the obscurity which reins in these subjects, and which puzzle the greatest adepts in political science.

The experience of ages, with the continued and combined labors of the most enlightened legislatures and jurists, has been equally unsuccessful in delineating the several objects and limits of different codes of laws and different tribunals of justice. The precise extent of the common law, and the statute law, the maritime law, the ecclesiastical law, the law of corporations, and other local laws and customs, remains still to be clearly and finally established in Great Britain, where accuracy in such subjects has been more industriously pursued than in any other part of the world. The jurisdiction of her several courts, general and local, of law, of equity, of admiralty, etc., is not less a source of frequent and intricate discussions, sufficiently denoting the indeterminate limits by which they are respectively circumscribed. All new laws, though penned with the greatest technical skill, and passed on the fullest and most mature deliberation, are considered as more or less obscure and equivocal, until their meaning be liquidated and ascertained by a series of particular discussions and adjudications. Language itself is imprecise and sometimes murky. Besides the obscurity arising from the complexity of objects, and the imperfection of the human faculties, the medium through which the conceptions of men are conveyed to each other adds a fresh embarrassment. The use of words is to express ideas. Perspicuity, therefore, requires not only that the ideas should be distinctly formed, but that they should be expressed by words distinctly and exclusively appropriate to them. But no language is so copious as to supply words and phrases for every complex idea, or so correct as not to include many equivocally denoting different ideas. Hence it must happen that however accurately objects may be discriminated in themselves, and however accurately the discrimination may be considered, the definition of them may be rendered inaccurate by the inaccuracy of the terms in which it is delivered. And this unavoidable inaccuracy must be greater or less, according to the complexity and novelty of the objects defined. When the Almighty himself condescends to address mankind in their own language, his meaning, luminous as it must be, is rendered dim and doubtful by the cloudy medium through which it is communicated.

Here, then, are three sources of vague and incorrect definitions: indistinctness of the object, imperfection of the organ of conception, inadequateness of the vehicle of ideas. Any one of these must produce a certain degree of obscurity. The convention, in delineating the boundary between the federal and State jurisdictions, must have experienced the full effect of them all.

The conflicting self-interest of large and small states marred the Constitution from a theoretical point of view. To the difficulties already mentioned may be added the interfering pretensions of the larger and smaller States. We cannot err in supposing that the former would contend for a participation in the government, fully proportioned to their superior wealth and importance; and that the latter would not be less tenacious of the equality at present enjoyed by them. We may well suppose that neither side would entirely yield to the other, and consequently that the struggle could be terminated only by compromise. It is extremely probable, also, that after the ratio of representation had been adjusted, this very compromise must have produced a fresh struggle between the same parties, to give such a turn to the organization of the government, and to the distribution of its powers, as would increase the importance of the branches, in forming which they had respectively obtained the greatest share of influence. There are features in the Constitution which warrant each of these suppositions; and as far as either of them is well founded, it shows that the convention must have been compelled to sacrifice theoretical propriety to the force of extraneous considerations.

The proposed constitution required compromise on other points. Nor could it have been the large and small States only, which would marshal themselves in opposition to each other on various points. Other combinations, resulting from a difference of local position and policy, must have created additional difficulties. As every State may be divided into different districts, and its citizens into different classes, which give birth to contending interests and local jealousies, so the different parts of the United States are distinguished from each other by a variety of circumstances, which produce a like effect on a larger scale. And although this variety of interests, for reasons sufficiently explained in a former paper, may have a salutary influence on the administration of the government when formed, yet every one must be sensible of the contrary influence, which must have been experienced in the task of forming it.

What the proposed constitution lacks in theoretical virtues, it makes up for by having established real-world consensus among the framers at the Constitutional Convention. Would it be wonderful if, under the pressure of all these difficulties, the convention should have been forced into some deviations from that artificial structure and regular symmetry which an abstract view of the subject might lead an ingenious theorist to bestow on a Constitution planned in his closet or in his imagination? The product of the Constitutional Convention was much better than anyone had a right to expect. The real wonder is that so many difficulties should have been surmounted, and surmounted with a unanimity almost as unprecedented as it must have been unexpected. It is impossible for any man of candor to reflect on this circumstance without partaking of the astonishment. It is impossible for the man of pious reflection not to perceive in it a finger of that Almighty hand which has been so frequently and signally extended to our relief in the critical stages of the revolution.

The near-unanimity of the Constitutional Convention is a tribute to the public-spiritedness and wisdom of those who gathered there. We had occasion, in a former paper, to take notice of the repeated trials which have been unsuccessfully made in the United Netherlands for reforming the baneful and notorious vices of their constitution. The history of almost all the great councils and consultations held among mankind for reconciling their discordant opinions, assuaging their mutual jealousies, and adjusting their respective interests, is a history of factions, contentions, and disappointments, and may be classed among the most dark and degraded pictures which display the infirmities and depravities of the human character. If, in a few scattered instances, a brighter aspect is presented, they serve only as exceptions to admonish us of the general truth; and by their lustre to darken the gloom of the adverse prospect to which they are contrasted. In revolving the causes from which these exceptions result, and applying them to the particular instances before us, we are necessarily led to two important conclusions. The first is, that the convention must have enjoyed, in a very singular degree, an exemption from the pestilential influence of party animosities the disease most incident to deliberative bodies, and most apt to contaminate their proceedings. The second conclusion is that all the deputations composing the convention were satisfactorily accommodated by the final act, or were induced to accede to it by a deep conviction of the necessity of sacrificing private opinions and partial interests to the public good, and by a despair of seeing this necessity diminished by delays or by new experiments.

PUBLIUS.

Links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #24: The United States Need a Standing Army—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #27: People Will Get Used to the Federal Government—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #30: A Robust Power of Taxation is Needed to Make a Nation Powerful

The Federalist Papers #35 A: Alexander Hamilton as an Economist

The Federalist Papers #35 B: Alexander Hamilton on Who Can Represent Whom

The Federalist Papers #36: Alexander Hamilton on Regressive Taxation

Ed Simon on Ludwig Wittgenstein →

I have a continuing interest in Ludwig Wittgenstein because my Mater’s thesis in Linguistics was on the Later Wittgenstein. See “Miles's Linguistics Master's Thesis: The Later Wittgenstein, Roman Jakobson and Charles Saunders Peirce.”

Sequencing of Projects, Continued

This post pushes the results in “Sequencing of Projects” further. To understand this post, you need to read “Sequencing of Projects” first. Here is a reminder of the notation:

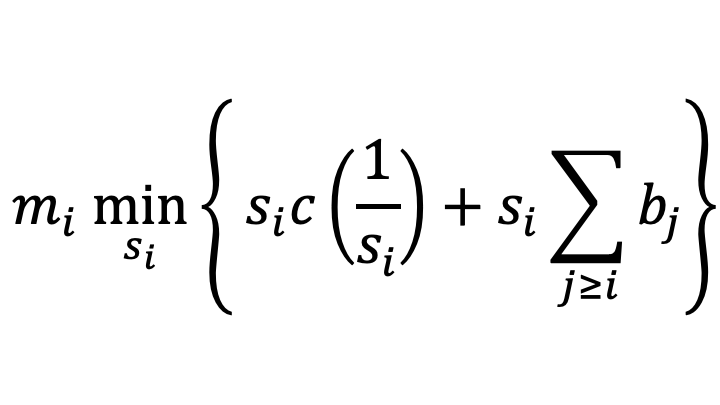

The objective is to minimize total cost:

Total Cost = Cost of Completing Projects + Cost of Delay in Getting the Benefits from Completed Projects

One thing I leave undone in “Sequencing of Projects” is determining which project should be done first after accounting for the fact that later projects should be done more slowly, so that changing the order optimally means changing how slowly each project is done.

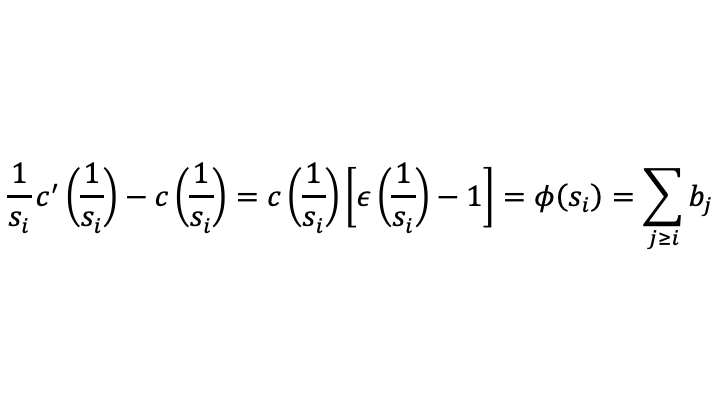

The first-order condition for the slowness of project i is:

Diagrammatically:

Both the downward slope and the convexity of phi(s_i) are important here. The downward slope follows from computing the first derivative of phi:

The second derivative of phi, which determines the curvature of phi, is:

Note the importance of the assumption that c’’’>0 for establishing the sign of phi’’. The assumption that c’’’(x_i)>0 is natural if one represents a maximum possible speed as cost going to infinity as that maximum possible speed is approached. A smooth function that goes up to infinity as it approaches a finite upper bound must have all positive derivatives as it approaches that upper bound.

Suppose some particular sequencing of projects has been proposed. Now consider switching the order of two consecutive projects in that proposed sequencing: A and B. Since this switch leaves unchanged the sequencing before these two projects, define b** as the sum of flow benefits from completing these two projects and all the projects sequenced after them and s** as the slowness optimal for that sum of flow benefits all waiting on completion of a project. Note that s** is, in fact, the optimal speed for whichever of projects A and B comes first between the two.

Let me determine which of [A, then B] or [B then A] with optimal slowness is better by looking at how much each improves on [A, then B] with the slowness of both A and B constrained to be s**.

As an intermediate good in making this calculation, I compute that the change in total cost from switching from [A, then B] with the slowness of both A and B constrained to be s** to [B, then A] with the slowness of both A and B constrained to be s** is

since switching to B, then A (with both at slowness s**) reduces the time to get to the benefit for B by how long project A takes, while the time to get to the benefit for A is increased by how long project B takes. Note that if the slownesses really were both constrained to be the same for both A and B, then the condition for A, then B being better would be:

or

But when the slownesses are freed up, there is another set of terms in comparing the total cost of [A, then B] to the total cost of [B, then A]. Adjusting the slowness of the second of the two projects to its optimum reduces total cost. That reduction in cost from slowing down the second project as compared to s** will be different depending on which project is second. The net reduction in total cost from slowing down a project is directly proportional to the magnitude of the project, because both the cost of completing the project and the cost of delay of things waiting on that project are proportional to the magnitude of the project. The other factor in the net reduction in total cost from slowing down a project can be shown geometrically as a triangle. The figures below show that triangle for both A and B. (I show the flow benefit from A as greater than the flow benefit of B.) Note that Triangle_A on the left is actually a function of b_B, while Triangle_B on the left is actually a function of b_A.

Including the adjustment of the slowness of the second project, the condition for switching from [A, then B] to [B, then A] to raise total costs is now:

Note that there is a shift to subtracting the magnitude of A times the Triangle for adjusting the pace of A instead of the corresponding product for B.

Using the fact that each Triangle is a function of the flow benefit of the other of the two projects, this is:

Rearranging:

Note that the curvature of phi guarantees that the function Triangle(b) grows faster than a quadratic in b. The message I get from this equation is that when the slowness is endogenized, a 1% change in the flow benefit b is more important in making a project more attractive to put first than is a 1% reduction in the magnitude m of the project. By contrast, if the slownesses were exogenously given, what would matter would be just the ratio b/m, which has a 1% increase in b and a 1% reduction in m equally important. So endogenizing the pace at which each project is done makes the benefit of each relatively more important in determining the best sequence.

Note that satisfying this condition for which of two consecutive projects should come first may not preclude reducing total cost be some other kind of rearrangement in the timing. That is one of the ways in which the problem if optimally sequencing projects is a difficult problem.

Book Recommendations for Economics →

When I posed the question on Twitter, great book recommendations came in from many people. Take a look at the thread!

Sharing Epiphanies

Link to the sermon above on YouTube

I am a Unitarian-Universalist lay preacher. I gave 12 sermons—annually from 2005 to 2016—to the Community Unitarian Universalists in Brighton. This post is my May 23, 2010 sermon “Sharing Epiphanies.” That brings to 10 those that are posted on this blog:

Sharing Epiphanies (including the video)

The Message of Mormonism for Atheists Who Want to Stay Atheists (video here)

Below is the newly edited text. (It will vary somewhat from the video above.) At the bottom of this post are links to some of my other posts on religion.

In this sermon, I mention my son Spencer’s suicide at the age of 20. For background, you can read what my wife Gail writes and what my daughter Diana writes about that.

On the first ephiphany, see also “Five Books That Have Changed My Life.” On the second epiphany, see also “There's One Key Difference Between Kids Who Excel at Math and Those Who Don't,” How to Turn Every Child into a 'Math Person', “Shane Parrish on Deliberate Practice” and “Daniel Coyle on Deliberate Practice.”

Abstract: Some of the most important things we learn in life are those lessons that come as a surprise. These surprises are what I mean by epiphanies. Sharing epiphanies with each other gives us all the chance to become wiser. I will share three epiphanies in my own life: (1) how I learned to respect positive thinking, (2) my shock when I learned that intelligence is not primarily an inborn quantity and (3) discovering the joys of "cleaning house."

I appreciate your inviting me back to give another sermon. If you are willing, I would love to come back every year for the next twenty years, if not more. Yesterday, I was looking back at the five sermons I have given here in the last five years. Last year I cribbed from David Foster Wallace to talk about “the egocentric illusion.” In the two years before that I explained my commitment to Unitarian-Universalism as a religion that does not require belief in the existence of God and so gives me space for my worship of the non-existent God whom our many-many-times great grandchildren may someday bring into existence. Then in my first two sermons here I gave my Credo—a statement of belief—and my “UU Vision”—a personal statement of the kind of world I would like to work toward creating.

Today I would like to return to a theme implicit in presenting my UU Vision. As you know, I am a refugee from Mormonism and do not believe that Mormonism is true. Nevertheless, I think that, sociologically, there are useful lessons to be drawn from Mormonism. At the congregational level Mormonism draws extra strength from a lay ministry in which almost every member of the congregation takes on a serious church assignment. What is perhaps even more remarkable is that Mormonism has a largely lay pulpit. On the first Sunday of every month, Mormon meetings are organized a bit like Quaker meetings in which anyone who feels moved to speak is encouraged to speak. The other Sundays, speakers are prearranged, with the duty of speaking rotating gradually through the entire congregation. Needless to say, the quality of the sermons is often not that high, but even the most dull of sermons allows people to get to know the speaker a bit better, and so helps to bind the congregation together a bit more strongly.

I do not think this exact pattern would suit Unitarian-Universalism all that well, but I do think it would be a very good thing to gradually increase the set of opportunities and the gentle encouragement for members of a congregation to prepare and share their thoughts with the whole congregation. In addition to sharing Credos [statements of what one believes] and reports of congregational activities, I am advocating the invention of additional forms of sharing, such as sharing UU visions--and today what I would like to call “sharing epiphanies.”

According to dictionary.com, one definition of epiphany is “an appearance or manifestation of a deity,” and certainly if anyone of you sees God, I hope you would share that experience, but what I have in mind is something much more modest. A more workaday meaning of “epiphany” is “a sudden, intuitive perception of or insight into the reality or essential meaning of something, usually initiated by some simple, homely, or commonplace occurrence or experience.” In other words, this kind of epiphany is a life lesson that comes by surprise, in the ordinary course of life.

In order to keep things interesting, let me insist on one essential characteristic of an epiphany: an epiphany should involve a clear change from thinking one way to thinking another way. Indeed, the most interesting epiphanies often involve a 180-degree reversal in thinking. So, to identify an epiphany in your own life, it pays to look for cases where you used to think something that you now think is wrong, in an important way.

Our former minister Ken Phifer [see 1, 2, 3] made a point of having exactly three subpoints within a section of a sermon. So taking that as my guide, I tried to think of three epiphanies in my life.

Let me start with how I learned to respect positive thinking. I was a very serious-minded child and as a teenager looked down on positive thinking because I felt it conflicted with facing reality squarely. That is, I was afraid that positive thinking would make me an unrealistic Pollyanna. Not a very macho image. Then, among my mother’s many books on pop psychology, I ran across the book Psycho-Cybernetics, by the plastic surgeon Maxwell Maltz. Maxwell Maltz argued that imagining things going well is a way of practicing for good outcomes. For example, he pointed to experiments in which people who imagined in detail the actions involved in sinking free throws gained almost as much skill as those who physically practiced.

It is hard to get across the effect this had on me. What I got from the book was that I could be a positive thinker and a flinty-eyed realist at the same time! The key was to realize that the positive thoughts were not a description of reality, but only a way to exercise my imagination to help me ready in case something good happened. Without contradiction, I could alternate between thinking like a flinty-eyed realist and thinking like a died-in-the-wool optimist and so be prepared for anything. Fortunately, though I sometimes forget this, I have found that spending a small fraction of the time being a flinty-eyed realist is enough to be prepared for the worst. Then I can spend the rest of the time being a cheerful optimist, and definitely be prepared for the best. My ship may never come in, but if it does, I will be ready!

For my other two epiphanies, fast forward to this past year. This past year has been a big year for me, in a very bad way. You may remember my son Spencer, who came with me on my last visit here. Last September, Spencer committed suicide. Needless to say, this was a big blow to us. I am both consoled and urged to patience by my research on happiness with coauthors which suggests that in two years we will be most of the way back toward feeling normal. After Spencer’s death, there were many nights I couldn’t sleep, so I built giant geometric shapes out of Magnetix—a magnetic building toy [now banned as being dangerous to children].

During the day, I increased my rate of reading books three or four times over. Right before Spencer’s death, I had read the book Intelligence and How to Get It: Why Schools and Cultures Count, by the University of Michigan Psychology professor Richard Nisbett. After Spencer’s death, in addition to reading a fantasy novel and several books on Roman history, I followed that up with the two books with the titles Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else by Geoff Colvin and The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How by Daniel Coyle. These three books all had the same basic point: intelligence, talent and skill are not fixed quantities we are born with, but are the outcomes of diligent effort and careful practice that focuses in on improving each weak point.

The thought that intelligence was more a matter of having opportunities and taking opportunities to do hard intellectual work than a matter of just being born smart came as a shock and a revelation to me. Since I was young, my identity has been wrapped up in being “the smartest kid on the block.” And there is no question that, like most Americans, but unlike most Chinese or Japanese, I assumed that being smart was something I was born with and only had to demonstrate. As I look back now, I notice the vast number of hours I spent reading the World Book encyclopedia, working on math problems, reading Isaac Asimov books on science and history, and walking around trying to think deep thoughts. But since I believed my level of intelligence was a quantity determined at birth, I was careful not to work too hard at my schoolwork, lest I give the lie to the idea that I was just naturally talented. It was OK to spend a lot of time studying things that would come up in future classes, but I would lose face if I studied too hard for the classes I was actually in! I say all of this just to indicate how firmly I believed that intelligence was a fixed inborn quantity.

I remember how surprised I was when one of my locker partners, whom I had thought of as an ordinary kid, showed up as a graduate student at Harvard when I was studying economics there. When his interests moved in an intellectual direction, he was extremely successful academically, and after being one of Stephen J. Gould’s students had a fascinating career digging up fossils at exotic locations and teaching geology. I am embarrassed now that I underestimated him back when I was in high school.

Believing that intelligence is a fixed inborn quantity causes many students to give up, thinking they can never learn. The psychologists Lisa Blackwell, Kali Trzesniewski and Carol Dweck went into a school and divided the students into two groups. One group was taught that studying could rewire the brain and raise intelligence. The idea that intelligence can be changed led these students to study harder and get better grades. The effect was especially strong for students who started out believing most strongly that intelligence is genetically determined. In Richard Nisbett’s words, “[Carol] Dweck reported that some of her tough junior high school boys were reduced to tears by the news that their intelligence was substantially under their control.” Those boys had an epiphany.

My third epiphany came from an unusual source. After a child dies, many families feel the urge to move to a different house so they won’t be beset by painful memories at every turn. I hate moving, so we didn’t even think seriously about that. What we did do was clean house. Before coming under my wife Gail’s influence, I was a pack rat, son of a pack rat. Gail, while good at letting go and getting rid of things to begin with, gained extra inspiration from watching the cable TV show “Clean House,” in which the lives of pack rats are transformed on camera. I can’t reproduce Gail’s pep talks about the virtues of slimming down our stock of things, but I know that it felt good to get rid of things. Our house is on a major street, so we were able to put things out front with a “Free” sign on them and watch them disappear within hours. I carted many boxes of books to give to the library for the used bookstore the “Friends of the Library” run. We took pictures of keepsakes we had been hanging onto for a long time and then gave them away or threw them out. I brought everything down from the attic for critical examination to see whether it should stay or go.

What has been most interesting about this whole process of cleaning house is the way the questions that come up in choosing whether to keep something or get rid of it are questions about what I want to do with the rest of my life.

Every time I decide to keep something, it is a reminder of something I want to do. Reinforcing those reminders, I had a new determination in the wake of Spencer’s death to do more of the things I have wanted to, but haven’t gotten to. Besides building geometric shapes with Magnetix, and reading regular books, I have made time to gradually work my way through a book on number theory, and for some reason I have been doggedly working my way through a stack of articles I had torn out of the Wall Street Journal to read later. I am determined to learn French. The theme for me is that everything that I have wanted to do should flow. Nothing that I really want to do should be totally stopped. I am at a point in my career where there is no reason to think that next year or the year after that will be any less busy than this year. So if I want to do something before I retire, I need to build it into my schedule now.

In a concept from the show “Clean House,” each object is a promise to oneself. It is often hard to get rid of old things because unused things represent broken promises to do something. Promises to oneself need to be resolved one way or another. For each ancient promise, I need to either keep the promise, or reconsider and release myself from the promise. No one is perfect. More to the point, we are all finite. We will never have time enough to do all of the things we might like to do. This is one of those lessons that I resist so much that I have to learn it over and over again.

I can express this third epiphany well by telling the story of my kindly neighbor from the street where I lived as a teenager. He said (more or less) “When you grow up, you will be able to do anything.” Naïve as I was, my heart misheard this as “When you grow up, you will be able to do everything.” But there is all the difference in the world between “anything” and “everything.” We have to choose. We might be able to have a lot, but we can’t “have it all.” What we do with the few years we have on this earth before we go to our grave determines, along with luck, which of all our dreams will become real and which of our dreams will remain only dreams. Don’t let the dreams that are most precious to you slip away if you can help it. As a first step, you need to figure out which dreams are the ones that are most important to you. Then, most painfully, you will have to figure out which dreams you can let go.

This same exercise of sorting through dreams and letting go of some needs to happen also at the collective level of families and congregations and nations—in ways that often affect in turn which individual dreams can be realized. There is no easy way to make these decisions. But they have to be made.

For us who are lucky enough to be part of democratic families, congregations and nations, the more we share what is in our hearts, the more likely it will be that dreams widely shared will prevail in those collective decisions. And in my own individual life, the more often I remind myself of what is truly important to me—and act accordingly—the more likely I am to get there.

References

Blackwell, Lisa S., Kali H. Trzesniewski and Carol Sorich Dweck, 2007. “Implicit Theories of Intelligence Predict Achievement Across an Adolescent Transition: A Longitudinal Study and an Intervention,” Child Development, 78 (January), 246-263.

Nisbett, Richard E. 2009. Intelligence and How to Get It: Why Schools and Cultures Count, Norton, New York.

Colvin, Geoff, 2008. Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else.

Daniel Coyle, 2009. The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How.

Other Posts on Religion:

Posts on Positive Mental Health and Maintaining One’s Moral Compass:

Co-Active Coaching as a Tool for Maximizing Utility—Getting Where You Want in Life

How Economists Can Enhance Their Scientific Creativity, Engagement and Impact

Judson Brewer, Elizabeth Bernstein and Mitchell Kaplan on Finding Inner Calm

Recognizing Opportunity: The Case of the Golden Raspberries—Taryn Laakso

Taryn Laakso: Battery Charge Trending to 0% — Time to Recharge

Savannah Taylor: Lessons of the Labyrinth and Tapping Into Your Inner Wisdom

Sequencing of Projects

In “How Fast Should a Project Be Completed?” I asked the question of how fast to do a project it does nothing for you when half-finished, but yields a continuing stream of benefits from the moment it is completed. My conclusion was the a project of that type should be completed quite fast unless the elasticity of the cost with respect to rate of progress gets high.

My example of a project was my efforts to learn German, with the idea that it will only be attractive to read German for fun once I have learned a vocabulary of 10,000 German words (using the methods I discuss in “The Most Effective Memory Methods are Difficult—and That's Why They Work”).

But I actually want to learn French and Spanish as well as German. What is the best way to approach multiple projects. For this post, I’ll assume each has a flow of benefits once completed, and not before, and that these benefits are additively separable, with no crowding out.

Let me first set out the notation:

Where it says “annual cost” above, it could have just as well said “daily cost,” because I assume that costs are additively separable across time and the model is in continuous time. That also means there is no direct production efficiency to be gained from working on more than one project at a time. Also, in this problem, all the efforts are under one’s own control—no waiting for coauthors or for a journal to get back to you. Needing to wait for someone else could be a reason to mix it up by working on another project while waiting for input on one.

The objective is to minimize total cost:

Total Cost = Cost of Completing Projects + Cost of Delay in Getting the Benefits from Completed Projects

Using the notation laid out above,

It is not a difficult task to show that given these assumptions circumstance, it is best to work on just one project at a time. For example, it can’t be optimal to be working on the first completed task and the second completed task at the same time. Just keep the pace of doing each project the same and do some rearrangement of effort timing to get the first project done sooner, without changing the moment at which both of the first two projects are completed. This will be better. The possibility of another rearrangement shows that you shouldn’t work on the third or any later completed task before the first task is completed. So only work on the first until it is done. Then consider all the projects after the first one and use the same argument over again.

So projects should be pursued one at a time here. What order should they be done in. Notationally, I have written things with numbers representing the sequencing of projects that is, in fact, optimal. But there are some necessary conditions for a proposed sequencing of projects to be optimal. In particular, it can’t be an optimal sequencing if it is possible to switch the order of two consecutive projects—holding the slowness with which each project is pursued—and reduce the total cost. Let’s call those two consecutive projects A and B. If the time it takes to do each project is held constant, then the path of the flow of benefits from projects completed before A and B won’t change and the path of the flow of benefits from projects completed after A and B won’t change, since the time when each of the other projects is completed and begins throwing off benefits is unchanged. Even for A and B, the time needed to complete all the previous projects is unchanged, and so can be ignored when considering whether switching the order of those two.

Thus, the order A, then B, can only be optimal if:

Subtract this from both sides of the inequality:

That yields this expression of the inequality necessary for A, then B to be optimal:

Changing the sign and taking the reciprocal preserves the direction of the inequality:

Finally, multiply by the product of the benefit flows of A and B and switch right and left to obtain this necessary condition for the order A, then B to be optimal:

This is a necessary condition because otherwise, switching the order of A and B while hold the slowness for A and the slowness for B fixed would reduce total cost. If the slownesses were all exogenously given, this condition for each consecutive pair would also be sufficient, since then—other than ties with equality on this condition—there is only one way to get an order that satisfies the necessary condition. If the slownesses were exogenously given, the projects should be done from the exogenous highest benefit/time required ratio b/[ms] to the lowest.

If the slownesses are endogenous, things are more complex. It is possible for both [A, then B] and [B, then A] to satisfy the necessary condition because, as I’ll show in a second, putting something earlier in the order increases the optimal speed—and reduces the optimal slowness—with which a project should be done. The reason is intuitive: the earlier a project is in the order, the more other projects are waiting for that early project to be completed, making it more urgent. Look closely and you can see that if the slowness of B is lower in the [B, then A] order, then the necessary condition might be satisfied for both [A, then B] and [B, then A]. And the sufficient condition is beyond the scope of this particular post. Nevertheless, the necessary condition above means that at the optimal slownesses and optimal sequencing, the benefit to required time ratio monotonically declines from one project to the next.

Now let me back up my claim that projects earlier in the sequence should be done faster. Pulling out the terms in the expression for total cost that involve s_i isolates the optimization subproblem for s_i. The optimal slowness is thus the solution to this optimization subproblem:

The magnitude of the project drops out of the first-order condition:

Calculating the first derivative of the function phi shows that it is is downward sloping in slowness s_i:

That justifies the way I have the graph at the top of this post. The greater the sum of benefits from this project and all subsequent projects, the faster this project should be done. (Faster = less slowly, lower s_i.)

Note that if the benefits of completion are not additive so that the marginal product of each project depends on the order, it makes it more complex to determine the right order, given any order the implication that earlier projects will optimally go at a quicker pace remains. Whatever the marginal product of later projects (assuming those marginal products are positive), those marginal products of later projects will add to the urgency of completing the first project in order to more expeditiously move on to later projects.

So I should study German even faster, given that I have French and Spanish lined up to study after that.

America’s Losing Battle Against Diabetes—Chad Terhune, Robin Respaut and Deborah Nelson →

Hat tip to Chris Kimball.

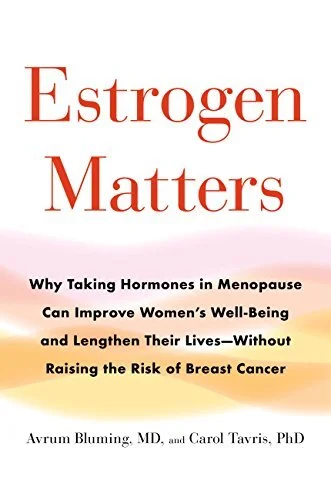

Standard Hormone Replacement Therapy Doesn't Cause Breast Cancer

In this post, I’ll expand on the claim I made in “Hormone Replacement Therapy is Much Better and Much Safer Than You Think” that there is no solid evidence that smoothly transitioning into hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) at the first signs of menopause causes breast cancer.

I strongly encourage you to read the book Estrogen Matters, by Avrum Bluming and Carol Tavris, to get the full argument. All the indented quotations in this post come from that book. Here, I’ll just give a taste.

First, to define the terms ERT and HRT, they write:

… women who have had hysterectomies and who subsequently start hormone therapy get estrogen alone (ERT), while women who have not undergone hysterectomies and who start hormone therapy receive estrogen plus progesterone (HRT).

There is a lot of evidence for a lack of correlation between HRT or ERT and breast cancer as HRT and ERT are normally used. Here are some of the points Avrum Bluming and Carol Tavris lay out:

A 1986 study led by epidemiologist Louise Brinton at the National Cancer Institute found no statistically significant increased risk of breast cancer among women on Premarin, even among those who had been taking it for more than twenty years.

A 1988 meta-analysis of twenty-two studies by Bruce Armstrong at the Research Unit in Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine of the University of Western Australia found no statistical association between ERT and breast cancer.

A 1991 study led by epidemiologist Julie Palmer at Boston University School of Medicine found no increased risk of breast cancer among Premarin users even after fifteen years of use.

A 1991 analysis of twenty-eight studies by biostatistician William Dupont and pathologist David L. Page at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine found no association between ERT and breast cancer.

In 1992, the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on this subject was published. Twenty-two years earlier, obstetrician-gynecologist and medical researcher Lila Nachtigall and her colleagues at New York University Langone Medical Center had randomly assigned 168 postmenopausal women who were continuously hospitalized in a mental institution to receive either HRT or placebo. After more than two decades, 11.5 percent of the women taking the placebo had developed breast cancer—but none of the women on HRT had.

Because women who undergo biopsies for benign breast disease have a slight increased risk of breast cancer, researchers followed 3,303 women who had benign breast biopsies performed at Vanderbilt University between 1958 and 1960. The median duration of the follow-up was seventeen years. In this study, published in 1989, women who were given estrogen following the biopsy—even those who had a family history of breast cancer—did not subsequently have an increased risk of breast cancer themselves.

Of course there were a few contradictory studies—there always are in medicine—but by the year 2000, major journals, research institutions, and leading oncologists were coming to the consensus that estrogen did not increase the risk of breast cancer.

…

According to a 1995 study by epidemiologist Janet Stanford of the University of Washington, “The use of estrogen with progestin (HRT) does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.… Compared with nonusers of menopausal hormones, those who used estrogen-progestin HRT for eight or more years had, if anything, a reduced risk of breast cancer.”

A 1995 article in the New England Journal of Medicine reported the first wave of results from the Nurses’ Health Study, which involved 121,700 female registered nurses who were followed from 1976 through 1992. The women who had used HRT at any point, even those who had been taking it for more than ten years, had no increased risk of breast cancer compared to women who never took HRT.

Some studies showed negative correlations with breast cancer:

In 1997, epidemiologist Thomas Sellers at the Moffitt Cancer Center of the University of Minnesota studied a random sample of 41,837 female Iowa residents between fifty-five and sixty-nine years of age to determine whether HRT was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in women with a family history of breast cancer. It was not.

In 2006, biostatistician Masahiro Takeuchi, at the National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo, studied nine thousand Japanese women and found that those who were on HRT were less likely to develop breast cancer than never-users.

What got the notion that HRT and ERT cause breast cancer into a large number of heads—likely including the head of your primary care physician—was the Women’s Health Initiative and how its results were spun. (“How its results were spun” is not an exaggeration. On that, at this point, let me refer you to the book. Here I’ll just focus on trying to interpret the science appropriately.)

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) had the great strength that it was a large randomized control trial:

The WHI was the largest prospective study in which women were randomized to take either hormones or a placebo and then followed over time.

The reason a randomized controlled trial (RCT) is important is that it could be that women who got HRT or ERT were following healthier practices in other ways, that were not captured by the data collected. Note that if this what confounded cross-sectional analyses and hid a bad effect of HRT or ERT in an RCT, it would mean that, at worst, any extra breast cancer risk from ERT or HRT could be fully counteracted by lifestyle changes likely to be reasonable since they would correspond to lifestyle differences actually seen across different people.

Being a randomized controlled trial made the Women’s Health Initiative expensive and gave it a lot of prestige, but it had other weaknesses I’ll discuss below. One thing to keep in mind is that even a relatively large randomized control trial would have low precision in its statistical estimates until a long enough time had passed for many women to have gotten breast cancer in the normal course of things. But, in what I regard as a mistake, the Women’s Health Initiative was stopped early on.

The initial results of the WHI were equivocal, within the bounds of what could be a statistical fluke from the particular women who were in the study and their idiosyncrasies:

Let’s start with the claim about breast cancer. The WHI investigators reported that women who were randomly assigned to take estrogen on its own had had no increased risk of breast cancer. Those who still had a uterus and were assigned to take the combination of estrogen and progestin had a small increased risk of breast cancer (1.26) when compared with women who were randomly assigned to a placebo. That number, 1.26, would mean a 26 percent increase in risk. What few noticed was this sentence: “The 26 percent increase in breast cancer incidence among the HRT group compared with the placebo group almost reached nominal statistical significance.” Almost means it did not reach statistical significance, and that means it could have been a spurious association.

Importantly, as time went on, the suggestive evidence for some additional breast cancer risk disappeared:

In 2006, in another update of this same cohort of women, the WHI reported that they found no increased risk of breast cancer among those same women randomized to combined estrogen-progestin treatment. The alleged increased risk—the one worth stopping the study for—had completely vanished.

Because the trial was stopped prematurely, we can’t know what the effects of HRT or ERT for longer would have been, but the lack of aftereffects certainly should be reassuring.

It is a stretch to read the WHI as showing any convincing evidence of higher breast cancer risk at all. But to the extent that you do read it that way, the weirdness of the sample means it wouldn’t say much about the way ERT and HRT are normally done. The biggest problem was that older women well past menopause were a dominant part of the sample, so the WHI can’t say much about the effects of going smoothly into ERT or HRT at the first sign of menopause. Another problem is that it is mostly speaking to breast cancer risk of women who have other problems, and so is less informative about any potential dangers of HRT or ERT for a woman who is healthy to begin with:

The WHI was heralded as being truly representative of women during and after menopause, and the WHI investigators repeatedly stated that all of the women they recruited were healthy at the outset of the study, but neither assertion was true. Fully 35 percent of the women were considerably overweight, and another 34 percent were obese; nearly 36 percent were being treated for high blood pressure; nearly half were either current or past cigarette smokers. Moreover, the median age of participants was sixty-three, long past the onset of menopause. Therefore, there is no credible reason for generalizing from the results of this study to the entire population of postmenopausal women—even though that was precisely what this randomized controlled study was supposed to do.

Above, I wrote “Note that if this what confounded cross-sectional analyses and hid a bad effect of HRT or ERT in an RCT, it would mean that, at worst, any extra breast cancer risk from ERT or HRT could be fully counteracted by lifestyle changes likely to be reasonable since they would correspond to lifestyle differences actually seen across different people.” To spell that out more, let me select from Avrum and Carol’s long list of risk ratios some of the more interesting risk ratios that given context to the preliminary (and possibly statistically fluke) result of a 1.26 risk ratio for breast cancer of HRT in the WHI. I’ll make my selected items into bullets without any ellipses in between. But what is after each bullets is a quotation. Avoiding something with a relative risk factor of more than 1.26 or doing something with a relative risk factor of less than 1/1.26 = .79 would cancel out a 1.26 risk factor from HRT if that risk factor from HRT turned out to be real. Here are my selected items:

Risk Factors Reported to Be Associated with Breast Cancer

Risk Factor: Dietary fiber intake Relative Risk 0.31

Risk Factor: Significant weight gain from age 21 to present Relative Risk: 0.52

Risk Factor: Garlic and onions 7 to 10 times a week Relative Risk: 0.52

Risk Factor: Fish oil Relative Risk: 0.68

Risk Factor: Aspirin Relative Risk: 0.80

Risk Factor: Coffee consumption more than 5 cups a day Relative Risk: 0.80

Risk Factor: Above average weight at the age of 12

Risk Factor: Exposure to light at night Relative Risk:

Risk Factor: Alcohol Relative Risk: 1.26

Risk Factor: French fries (1 additional serving per week during preschool years) Relative Risk: 1.27

Risk Factor: Night-shift work Relative Risk: 1.51

Father at least 40 years old at patient’s birth (premenopausal breast cancer) Relative Risk: 1.90

Risk Factor: Antibiotic use for more than 1,001 days Relative Risk: 2.07

Risk Factor: Increased carbohydrate intake Relative Risk: 2.22

Risk Factor: Calcium channel blocker for more than 10 years Relative Risk: 2.40

Outside the realm of breast cancer, the risk ratio for tobacco smoking as a risk factor for lung cancer is 26.07.

I find Estrogen Matters a very important and useful book. It is good to remember that Avrum Bluming is an MD, trained just as well as your primary care physician, and probably quite a bit smarter than your primary care physician. Of course, your primary care physician knows things about you in particular that a book doesn’t reflect. So if your primary care physician advises against ERT or HRT for you based on unusual things about you in particular, you should take that very seriously. But if your primary care physician tends to oppose HRT and ERT across the board, it is probably because they are misinformed. Don’t be afraid to argue with your primary care physician; you can say you might change your mind if they read the book and give you a good argument after that. Also, you might be surprised at how different the opinions of different physicians are. There are some dangers to doctor shopping—and certainly some extra costs given the usual managed care—but it might be worth it in this case.

In this post I emphasized the absence of a breast cancer cost to HRT and ERT. Make sure to read “Hormone Replacement Therapy is Much Better and Much Safer Than You Think” to see more about the benefits. And both of these posts are meant to motivate you to read the book before you make any decision about ERT or HRT for yourself. You need to read the book so that your primary care physician doesn’t railroad you.

I don’t mean to say that the book is totally without flaws. There is some overemphasis of conventional significance levels, when it probably makes more sense to be a Bayesian in this context. And while I tried to provide context, breast cancer is common enough that even with the quite high survival rates for women who get breast cancer, I can’t dismiss a risk ratio of 1.26 as small if it were real and applied to your situation, which it probably doesn’t. But many of the known benefits of HRT and ERT are quite large compared to this, even it were real and applied to your situation. Nevertheless the book is great!

For organized links to other posts on diet and health, see:

Noah Smith: Let's Cheer the Success of the US Punitive Expedition in Afghanistan and Accept the Limits to What a US Occupation Can Do →

I wish the commentators in major newspapers were as insightful as Noah is.

The Federalist Papers #36: Alexander Hamilton on Regressive Taxation

Taxes are hated. We could make them hated less; I talk about that in “Scott Adams's Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich,” “No Tax Increase Without Recompense” and in the other links in “How and Why to Expand the Nonprofit Sector as a Partial Alternative to Government: A Reader’s Guide.” In many ways the US tax system is unnecessarily hateful. For example, while many other countries calculate people’s tax for them, the US requires people to calculate their own taxes or pay a tax preparer. (One reason the US does this is because of the tax preparation lobby. The tax software lobby also gets its strokes; see “Brian Flaxman—A Tale of Bipartisanship and Financial Interests: The Taxpayer First Act of 2019.”)

In addition to the gratuitous ways in which our current tax system is hateful, there is an unavoidable tension between (a) being responsive to the fact that a dollar means a lot more to a poor person than to a rich person and (b) we want to make it attractive for people to become rich by doing things that are helpful to society, which means that once we have blocked ways of getting rich that are not helpful to society, we still need to arrange things so it is attractive to become rich. Although we can do some other things to make it attractive to be rich (the topic of “Scott Adams's Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich”), financial incentives are likely to be part of how we give people incentives to be ambitious and to work hard. That puts a limit on how quickly tax owed can go up with income—too fast and the incentive to become rich is lessened. The tension between the value of redistribution toward the poor rather than away from the poor and the need for incentives for people to be ambitious and work hard is the topic of my first post on this blog: “What is a Supply-Side Liberal?

If everyone were identical, anything other than a head tax would be stupidity incarnate. That is the theme of “The Flat Tax, The Head Tax and the Size of Government: A Tax Parable.” The only reason to have taxes that go up with income at all is that some people have a lower ability to earn than others—or a genuinely greater need for spending than others—because of forces beyond their control. To the extent that we can directly measure these forces beyond people’s control, we should make taxes depend on those things rather than on income. I talk about that in “Why Taxes are Bad.” But our ability to directly measure the forces beyond people’s control in a minimally controversial way, while rapidly improving (especially on the genetic front), is still embryonic.

Alexander Hamilton, in the Federalist Papers #36, recognizes the problems with taxes that fall just as heavily in absolute terms on the poor as on the rich. He argues that, given the poor-rich variation out there, such taxes are so detestable that elected officials at any level of government are likely to be restrained in using taxes whose magnitude has too low a correlation with being rich.

Here are some key passages in which Alexander Hamilton writes against head taxes (=“poll taxes”) in the Federalist Papers #36, separated by bullets, with emphasis in bold added within longer passages:

the frightful forms of odious and oppressive poll-taxes

if the provision is to be made by the Union that the capital resource of commercial imposts, which is the most convenient branch of revenue, can be prudently improved to a much greater extent under federal than under State regulation, and of course will render it less necessary to recur to more inconvenient methods; and with this further advantage, that as far as there may be any real difficulty in the exercise of the power of internal taxation, it will impose a disposition to greater care in the choice and arrangement of the means; and must naturally tend to make it a fixed point of policy in the national administration to go as far as may be practicable in making the luxury of the rich tributary to the public treasury, in order to diminish the necessity of those impositions which might create dissatisfaction in the poorer and most numerous classes of the society.

Happy it is when the interest which the government has in the preservation of its own power, coincides with a proper distribution of the public burdens, and tends to guard the least wealthy part of the community from oppression!

As to poll taxes, I, without scruple, confess my disapprobation of them; and though they have prevailed from an early period in those States [The New England States.] which have uniformly been the most tenacious of their rights, I should lament to see them introduced into practice under the national government.

But does it follow because there is a power to lay them that they will actually be laid? Every State in the Union has power to impose [head] taxes of this kind; and yet in several of them they are unknown in practice.

Other than points that are repetitive of what Alexander Hamilton said in earlier numbers of the Federalist Papers, the rest of the Federalist Papers #36 is devoted to arguing that the federal government would be able to deal with details of tax administration as well as the state governments—often using the same approaches and potentially using many of the same people for advice and execution—and that the federal government will not put itself needlessly in conflict with state governments in its tax policy.

Tax policy has always been one of the most contentious areas of politics. I wish the insights of the New Dynamic Public Finance and other sophisticated theoretical treatments of optimal taxation could filter down much more into practical debates over tax policy. Two things would be very helpful there: more blog posts (including guest posts) by economists who are engaged in research on optimal taxation and a more accessible textbook covering optimal taxation, including the New Dynamic Public Finance. (Though he is a clear writer, Narayana Kocherlakotas lectures in book form, entitled “The New Dynamic Public Finance,” are not accessible enough.)

Below is the full text of the Federalist Papers #36. See if you agree with the characterization of the content that I gave above. At the bottom of this post are links to all of my previous posts on the Federalist Papers.

FEDERALIST NO. 36

The Same Subject Continued: Concerning the General Power of Taxation

From the New York Packet

Tuesday, January 8, 1788.

Author: Alexander Hamilton

To the People of the State of New York: