The Golden Mean as Concavity of Objective Functions

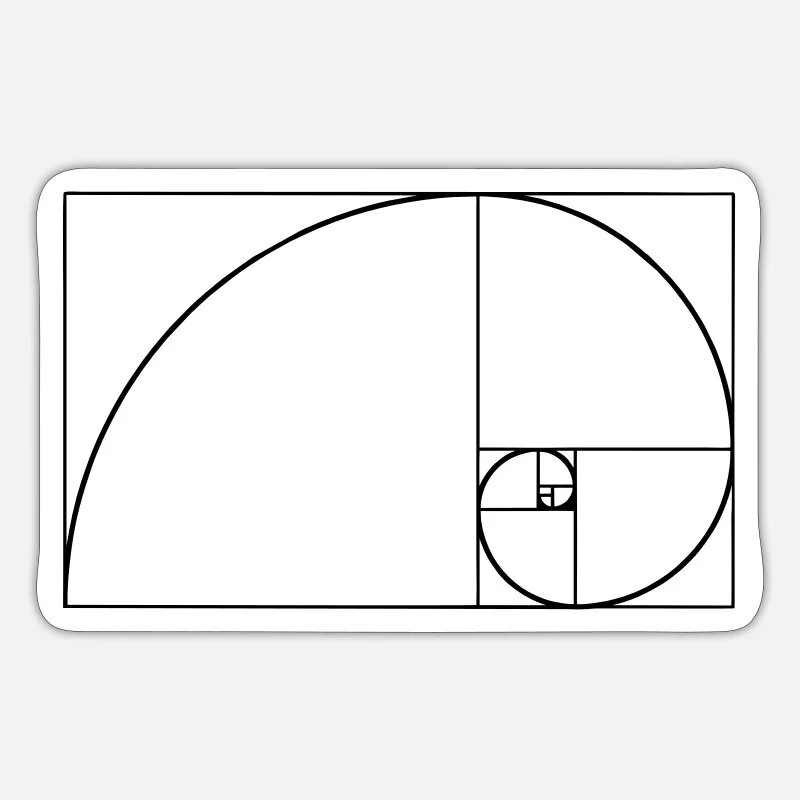

The “Golden Ratio” corresponds to a rectangle where taking a square out of the rectangle leaves behind a smaller rectangle that is similar to the original rectangle. It is sometimes called the “Golden Mean.” Felicitously, the illustration above of the Golden Mean in action also provides a concave function, if you look at only the top of the curve..

The Wikipedia article “Golden mean (philosophy)” currently begins:

The golden mean or golden middle way is the desirable middle between two extremes, one of excess and the other of deficiency. It appeared in Greek thought at least as early as the Delphic Maxim nothing to excess and emphasized in later Aristotelian philosophy

It gives the example of recklessness and cowardice as the two contrasting vices; courage is the golden mean between recklessness and cowardice.

Where there is a golden mean, we often have maxims that seem like opposites, but can be thought of as both pointing to the golden mean. Think of the two maxims “Haste makes waste” and “They who hesitate are lost.” Unfortunately, people often listen only to the maxim they interpret as advising going further toward an extreme rather than realizing that one is meant for other people; they should be paying most attention to the contrasting maxim that could tug them toward the golden mean.

In economics, the golden mean shows up as the idea that there is often an interior optimum when the objective function is concave.

Despite being trained in the use of concave functions in economics, I find myself often lapsing into the idea that if a little is good, then a lot must be better. That would be true if the objective function were linear, but it often isn’t. Moderation in all things!

Except that sometimes the objective function is linear, or close to linear. Here are two important examples (neither of which is original to me):

Suppose the objective function is stated in terms of a probability, and your preferences are expected utility preferences. If there are two possible outcomes, you always want a higher probability of the better outcome. There is no gain to flipping a coin between the two outcomes to “get something in the middle.”

Suppose you want to give money to charity out of pure altruism. You aren’t trying to look good; you aren’t trying to make yourself feel good; you are just trying to do the most good in the world. If you are thinking of giving to large charities for which the amount of money you are giving is small compared to the total funds used by that charity, the marginal benefit is essentially the same for the last dollar you give as for the first dollar you give. In this case, you should just go with whichever charity you think can do the most good with every extra dollar, without worrying that the benefit from an extra dollar will be affected by your giving.

These are important examples, but usually the objective function is concave and extremes are a bad idea.

The bulk of corner solutions, where it is the best choice to go to an edge are because the edge is not extreme at all. In cases where the edge is close in, there can be quite a bit of concavity, yet the corner solution still be the right answer. (The curve is bending to have a lower slope, but is still upward-sloping when you hit the boundary.) For example, unless you you think the covariance between what economists are paid and the stock market is not only positive, but quite high, you should put 100% of your retirement savings contributions into risky assets as a new assistant professor, because “extreme” is measured by the stock of risky assets you have relative to the value of your full wealth including your human capital. It will be a while before you accumulate enough in your retirement savings accounts for those accounts to be a big fraction of the present-discounted value of your lifetime labor income. That is, the stock/flow distinction combined with mentally integrating human capital into your portfolio means that 100% of the contribution flow in the first while toward risky assets isn’t really extreme at all. After you have accumulated quite a bit in your retirement savings account, then you can reassess.

Although I have only a few clients, I am a certified life coach. It makes me happy when economics can feed into life coaching—as in this concept of the Golden Mean.

Don’t Miss These Posts Related to Positive Mental Health and Maintaining One’s Moral Compass:

Co-Active Coaching as a Tool for Maximizing Utility—Getting Where You Want in Life

How Economists Can Enhance Their Scientific Creativity, Engagement and Impact

Judson Brewer, Elizabeth Bernstein and Mitchell Kaplan on Finding Inner Calm

Recognizing Opportunity: The Case of the Golden Raspberries—Taryn Laakso

Taryn Laakso: Battery Charge Trending to 0% — Time to Recharge

Savannah Taylor: Lessons of the Labyrinth and Tapping Into Your Inner Wisdom