The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

Steven Pinker’s contention in The Better Angels of Our Nature that violence has declined over the centuries has the corollary that violence was worse in the past. Accordingly, writing more than two and a quarter centuries ago, Alexander Hamilton argues that neighboring nations will almost inevitably be drawn into war with one another. At a minimum, this should make one appreciate the singularity in human history of the degree of 21st-century peace that exists between the US and Canada, between the US and Mexico and between many other pairs of neighboring nations around the world.

Viewing the 18th-century world, Alexander Hamilton points to many human motives leading to war in the first half of The Federalist #6, “Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States.” In particular, he writes:

“… men are ambitious, vindictive, and rapacious.”

Some love power, while others hate or fear the power of others.

Some love riches even if those riches are to be had at the expense of the lives of fellow human beings.

There are a vast number of idiosyncratic motives that can lead to war.

For the first three of these points, I put the relevant passages in the quoted text below in bold italics. For the fourth, I add bold subheadings for different individuals who displayed idiosyncratic motives for fomenting war. I also spell out in square brackets the notes Alexander Hamilton provides.

|| Federalist No. 6 ||

Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States

For the Independent Journal.

Author: Alexander Hamilton

To the People of the State of New York:

THE three last numbers of this paper have been dedicated to an enumeration of the dangers to which we should be exposed, in a state of disunion, from the arms and arts of foreign nations. I shall now proceed to delineate dangers of a different and, perhaps, still more alarming kind--those which will in all probability flow from dissensions between the States themselves, and from domestic factions and convulsions. These have been already in some instances slightly anticipated; but they deserve a more particular and more full investigation.

A man must be far gone in Utopian speculations who can seriously doubt that, if these States should either be wholly disunited, or only united in partial confederacies, the subdivisions into which they might be thrown would have frequent and violent contests with each other. To presume a want of motives for such contests as an argument against their existence, would be to forget that men are ambitious, vindictive, and rapacious. To look for a continuation of harmony between a number of independent, unconnected sovereignties in the same neighborhood, would be to disregard the uniform course of human events, and to set at defiance the accumulated experience of ages.

The causes of hostility among nations are innumerable. There are some which have a general and almost constant operation upon the collective bodies of society. Of this description are the love of power or the desire of pre-eminence and dominion--the jealousy of power, or the desire of equality and safety. There are others which have a more circumscribed though an equally operative influence within their spheres. Such are the rivalships and competitions of commerce between commercial nations. And there are others, not less numerous than either of the former, which take their origin entirely in private passions; in the attachments, enmities, interests, hopes, and fears of leading individuals in the communities of which they are members. Men of this class, whether the favorites of a king or of a people, have in too many instances abused the confidence they possessed; and assuming the pretext of some public motive, have not scrupled to sacrifice the national tranquillity to personal advantage or personal gratification.

Pericles. The celebrated Pericles, in compliance with the resentment of a prostitute, [Aspasia, vide Plutarch's Life of Pericles] at the expense of much of the blood and treasure of his countrymen, attacked, vanquished, and destroyed the city of the SAMNIANS. The same man, stimulated by private pique against the MEGARENSIANS, [Plutarch’s Life of Pericles] another nation of Greece, o] another nation of Greece, or to avoid a prosecution with which he was threatened as an accomplice of a supposed theft of the statuary Phidias, [Plutarch’s Life of Pericles] or to get rid of the accusations prepared to be brought against him for dissipating the funds of the state in the purchase of popularity, [Plutarch’s Life of Pericles: Phidias was supposed to have stolen some public gold, with the connivance of Pericles, for the embellishment of the statue of Minerva.] or from a combination of all these causes, was the primitive author of that famous and fatal war, distinguished in the Grecian annals by the name of the PELOPONNESIAN war; which, after various vicissitudes, intermissions, and renewals, terminated in the ruin of the Athenian commonwealth.

Cardinal Wolsey. The ambitious cardinal, who was prime minister to Henry VIII., permitting his vanity to aspire to the triple crown, [worn by the popes] entertained hopes of succeeding in the acquisition of that splendid prize by the influence of the Emperor Charles V. To secure the favor and interest of this enterprising and powerful monarch, he precipitated England into a war with France, contrary to the plainest dictates of policy, and at the hazard of the safety and independence, as well of the kingdom over which he presided by his counsels, as of Europe in general. For if there ever was a sovereign who bid fair to realize the project of universal monarchy, it was the Emperor Charles V., of whose intrigues Wolsey was at once the instrument and the dupe.

The influence which the bigotry of one female, [Madame de Maintenon] the petulance of another, [Duchess of Marlborough] and the cabals of a third, [Madame de Pompadour] had in the contemporary policy, ferments, and pacifications, of a considerable part of Europe, are topics that have been too often descanted upon not to be generally known.

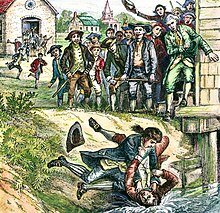

To multiply examples of the agency of personal considerations in the production of great national events, either foreign or domestic, according to their direction, would be an unnecessary waste of time. Those who have but a superficial acquaintance with the sources from which they are to be drawn, will themselves recollect a variety of instances; and those who have a tolerable knowledge of human nature will not stand in need of such lights to form their opinion either of the reality or extent of that agency. Perhaps, however, a reference, tending to illustrate the general principle, may with propriety be made to a case which has lately happened among ourselves. If Shays had not been a DESPERATE DEBTOR, it is much to be doubted whether Massachusetts would have been plunged into a civil war.

Given the flaws of human nature, it is a wonder that wars are as infrequent as they are now. In any case, as Alexander Hamiltonian contends, trying to bring neighboring states into a supranational organization is one way to try to reduce the frequency of war. For example, despite the tensions and resentments between countries within the European Union, we do not worry that much about full-scale armed conflict between neighboring nations within the European Union.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats