Having tweeted that John Taylor’s op-ed this morning, “Fed Policy is a Drag on the Economy” was “extraordinarily bad analysis,” I need to back up my view. Let me go point by point. Not all of John’s points are equally problematic.

1. Uncertainty about the effects of unwinding the Fed’s large asset positions in long-term government bonds and in mortgage-backed assets. John writes:

At the very least, the policy creates a great deal of uncertainty. People recognize that the Fed will eventually have to reverse course. When the economy begins to heat up, the Fed will have to sell the assets it has been purchasing to prevent inflation.

If its asset sales are too slow, the bank reserves used to finance the original asset purchases pour out of the banks and into the economy. But if the asset sales are too fast or abrupt, they will drive bond prices down and interest rates up too much, causing a recession. Those who say that there is no problem with the Fed’s interest rate and asset purchases because inflation has not increased so far ignore such downsides.

Unless the Fed is at the zero lower bound, its key tool is the federal funds rate that banks charge each other overnight. When it is time to raise rates above zero, the Fed can use movements in the federal funds rate–which have effects it understands from long experience. Although there is some uncertainty surrounding the exact size of the effects as the Fed unwinds its positions in long-term government bonds and mortgage-backed securities, the Fed is quickly gaining experience in that regard. More importantly, the overwhelming fact is that, when the short-term federal funds rate is held fixed the effects of balance sheet monetary policy on aggregate demand are small relative to the size of the positions involved, as I discussed in my post “Trillions and Trillions: Getting Used to Balance Sheet Monetary Policy.”

More polemically, it is worth pointing out that it is implausible for critics of Fed policy to say that (holding short-term rates fixed) changes in the holdings of long-term government bonds and mortgage-backed securities have no power to stimulate aggregate demand when the economy is in a slump, but going in the other direction, could have a dangerously powerful negative effect on aggregate demand once the economy is on the mend and asset positions are pulled back. The truth is that these effects were always likely to be modest in both directions, relative to the sizes of the assets purchases or sales involved. The power of balance sheet monetary policy is that these modest effects can be multiplied by huge movements in asset positions when necessary. But the very need to use huge movements in asset positions to get substantial effects should be reassuring when we contemplate unwinding those positions.

2. Low interest rates as fuel for speculation. Here, he says

The Fed’s current zero interest-rate policy also creates incentives for otherwise risk-averse investors—retirees, pension funds—to take on questionable investments as they search for higher yields in an attempt to bolster their minuscule interest income.

I can’t make sense of this statement without interpreting it as a behavioral economics statement about some combination of investor ignorance and irrationality and fraudulent schemes that prey on that ignorance and irrationality. The often-repeated claim that low interest rates lead to speculation cries out for formal modeling. I don’t see how such a model can work without some combination of investor ignorance and irrationality and fraudulent schemes preying on that ignorance and irrationality. (That is, I don’t see how the claim could hold in a model with rational agents and no fraud.) Whatever combination of investor ignorance and irrationality and fraudulent schemes preying on that ignorance an irrationality a successful model uses are likely to have much more powerful implications for financial regulation than for monetary policy. It is cherry-picking to point to implications of a not-fully-specified model for monetary policy and ignore the implications of that not-fully-specified model for financial regulation.

3. Low rates and zombie loans.

The low rates also make it possible for banks to roll over rather than write off bad loans, locking up unproductive assets.

This is one of John’s best and most interesting points. It is a quirk of traditional loan contracts that the repayment rates expected by lenders are sometimes slower when nominal interest rates are low. This is a place where the free market should do its magic, with lenders making sure that the rates at which they are supposed to be repaid are adequate to help them identify badly-performing loans early on. The free market will get better at this the more experience businesses have with low nominal interest rate environments.

4. Political economy effects of low interest rates.

And extraordinarily low rates support and feed the spending appetites of Congress and the president, increasing deficits and debt.

As I wrote in “What to Do When the World Desperately Wants to Lend Us Money,” there are many ways that it is completely appropriate for the government to take low (real) interest rates into account in spending decisions. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be worried about the long-run balance between taxing and spending. Bill Clinton explained the balance of short-run and long-run issues well when he said:

Now, let’s talk about the debt. Today, interest rates are low, lower than the rate of inflation. People are practically paying us to borrow money, to hold their money for them.

But it will become a big problem when the economy grows and interest rates start to rise. We’ve got to deal with this big long-term debt problem or it will deal with us. It will gobble up a bigger and bigger percentage of the federal budget we’d rather spend on education and health care and science and technology. It — we’ve got to deal with it.

I actually think this point is well understood by policy makers, but I wish all of their constituents understood it better. In any case, tight monetary policy to make voters worry more about the national debt seems a strange alternative to educating the voters about the debt problem.

5. Issues of institutional design and what the scope of the Fed’s responsibilities should be.

More broadly, the Fed’s excursion into fiscal policy and credit allocation raises questions about its institutional independence and accountability. This reduces public confidence in the central bank.

I agree with this statement. It is clear that there are important issues of institutional design for dealing with financial crises in order to preserve the public’s trust in institutions after the handling a financial crisis. I also interpret John’s statement as referring to ongoing balance sheet monetary policy, rather than just the emergency stabilization of the financial system-There I agree with this statement as well, as can be seen in my Quartz column “Why the US needs its own sovereign wealth fund.” In the absence of electronic money (on electronic money, see my post “Paper Currency Policy: A Primer”), purchases of a wide range of assets is crucial once short-term rates hit zero, but there is no reason the purchase of long-term or risky assets needs to be done by the Fed. Confidence in the Fed would be greater if unavoidably controversial assets were taken over by another agency–the US Sovereign Wealth Fund that I propose. As long as asset purchases by the US Sovereign Wealth Fund are sufficiently large, careful calibration of monetary policy can be left to the Fed, which would retain plenty of tools to avoid over-stimulation of the economy. This division of labor would allow the US Sovereign Wealth Fund to serve as a political lightning rod for the Fed, which in turn would help preserve the independence of monetary policy.

6. Effects of US monetary policy on the monetary policy of other countries.

There is yet another downside. Foreign central banks—whether they like it or not—tend to follow other central banks’ easy-money policies to prevent their currency from appreciating sharply, which would put their exporters at a disadvantage. The recent effort of the new Japanese government to force quantitative easing on the Bank of Japan and thus resist dollar depreciation against the yen vividly makes this point. This global increase in money risks commodity booms and busts as we saw in 2011 and 2012.

Here is my perspective on this:

- There is a global slump.

- This calls for stimulative monetary policy globally.

- Therefore, it is good that expansionary US monetary policy helps to inspire expansionary monetary policy by other countries.

The effect of monetary stimulus on commodity prices is a very interesting phenomenon that deserves a better treatment at some later date, but is not a reason to avoid monetary stimulus when monetary stimulus is called for.

7. Forward guidance as a price ceiling causing disequilibrium??? Finally, let’s turn to John’s most remarkable claim–the one that inspired my statement that his op-ed had “extraordinarily bad analysis.” John writes:

…a basic microeconomic analysis shows that the policies perversely decrease aggregate demand and increase unemployment while they repress the classic signaling and incentive effects of the price system.

Consider the “forward guidance” policy of saying that the short-term rate will be near zero for several years into the future. The purpose of this guidance is to keep longer-term interest rates down and thus encourage more borrowing. A lower future short-term interest rate reduces long-term rates today because portfolio managers can, in a form of arbitrage, easily adjust their portfolio mix between long-term bonds and a sequence of short-term bonds.

So if investors are told by the Fed that the short-term rate is going to be close to zero in the future, then they will bid down the yield on the long-term bond. The forward guidance keeps the long-term rate low and tends to prevent it from rising. Effectively the Fed is imposing an interest-rate ceiling on the longer-term market by saying it will keep the short rate unusually low.

The perverse effect comes when this ceiling is below what would be the equilibrium between borrowers and lenders who normally participate in that market. While borrowers might like a near-zero rate, there is little incentive for lenders to extend credit at that rate.

This is much like the effect of a price ceiling in a rental market where landlords reduce the supply of rental housing. Here lenders supply less credit at the lower rate. The decline in credit availability reduces aggregate demand, which tends to increase unemployment, a classic unintended consequence of the policy.

Research presented at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association this month by Eric Swanson and John Williams of the San Francisco Fed is consistent with this view of credit markets. It shows that during periods of forward guidance, the long-term interest rate does not adjust to events that shift supply or demand as it does in normal periods. In addition, while credit to corporate businesses is up 12% over the past two years, credit has declined to noncorporate businesses where the low rate is more likely to be a disincentive for lenders. Peter Fisher, head of fixed income at the global investment-management firm BlackRock and a former Fed and Treasury official, wrote in September: “[A]s they approach zero, lower rates … run the significant risk of perversely discouraging the lending and investment we need.”

This is just wrong. To the extent that forward guidance has bite, the Fed is promising to shift the demand curve for assets in the future and thereby get to a particular equilibrium interest rate. This is not at all like rent control. The right analogy is, say, New York City getting rents to come down by reducing making it easier to get a building permit, or by subsidizing the building of new apartments. The Fed is pushing asset prices up and interest rates down by a combination of buying assets now and promising to buy them in the future. There is a world of difference between a market intervention in which the government contributes to supply and demand and a price floor or ceiling. By buying assets, and promising to buy them in the future, the Fed is lowering an equilibrium interest rate. The details of the pattern of buying assets and promising to buy them in the future tends to keep the equilibrium interest rate at a certain level.

The fact that the Fed acts by changing the equilibrium interest rate matters, because John’s claim that lowering the interest rate will reduce the quantity of investment would hold only if what the Fed is doing really did act like an interest rate ceiling that makes asset demand lower than asset supply. But what the Fed is doing is adding to asset demand; the equilibrium between the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded continues to hold. To translate into the effect on loans for construction, the purchase of equipment and consumer durables, or to fund startups, strong asset demand contributes to the supply of loans, both because banks issue assets to raise money for loans and because loans can be packaged into assets. Anyone issuing and selling assets to raise funds can sell them much more easily when demand for assets is strong. Currently, the Fed is contributing in important ways to the demand for assets now and the expected demand for assets in the future. This makes loans easier and stimulates investment in buildings, equipment, etc.

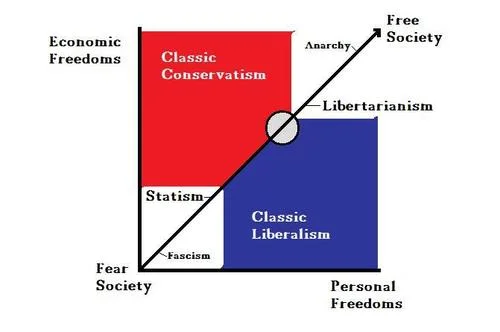

The bottom line is that it leads to very bad policy analysis if Fed asset purchases and promises of future asset purchases are mischaracterized as the kind of interest rate ceiling that leads to disequilibrium. Interest rate ceilings come in two types:

- interest rate ceilings that cause the supply of assets on the seller side (representing borrowing) to exceed the demand for assets on the buyer side (representing lending);

- interest rate “ceilings” that come from a commitment to buy as many assets as it takes to keep the equilibrium interest rate down at a certain level.

John Taylor confuses these two types of interest rate ceilings.

Update: Also see "Contra Randal Quarles."