On August 18, 2019, I posted “On Being a Copy of Someone's Mind.” I was intrigued to see from the teaser for Michael Graziano’s new book Rethinking Consciousness: A Scientific Theory of Subjective Experience, published as an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal on September 13, 2019, that Michael Graziano has been thinking along similar lines.

Michael explains the the process of copying someone’s mind (obviously not doable by human technology yet!) this way:

To upload a person’s mind, at least two technical challenges would need to be solved. First, we would need to build an artificial brain made of simulated neurons. Second, we would need to scan a person’s actual, biological brain and measure exactly how its neurons are connected to each other, to be able to copy that pattern in the artificial brain. Nobody knows if those two steps would really re-create a person’s mind or if other, subtler aspects of the biology of the brain must be copied as well, but it is a good starting place.

Michael nicely describes the experience of the copy, which following Robin Hanson I call an “em,” short for “brain emulation” in “On Being a Copy of Someone's Mind”:

Suppose I decide to have my brain scanned and my mind uploaded. Obviously, nobody knows what the process will really entail, but here’s one scenario: A conscious mind wakes up. It has my personality, memories, wisdom and emotions. It thinks it’s me. It can continue to learn and remember, because adaptability is the essence of an artificial neural network. Its synaptic connections continue to change with experience.

Sim-me (that is, simulated me) looks around and finds himself in a simulated, videogame environment. If that world is rendered well, it will look pretty much like the real world, and his virtual body will look like a real body. Maybe sim-me is assigned an apartment in a simulated version of Manhattan, where he lives with a whole population of other uploaded people in digital bodies. Sim-me can enjoy a stroll through the digitally rendered city on a beautiful day with always perfect weather. Smell, taste and touch might be muted because of the overwhelming bandwidth required to handle that type of information. By and large, however, sim-me can think to himself, “Ah, that upload was worth the money. I’ve reached the digital afterlife, and it’s a safe and pleasant place to live. May the computing cloud last indefinitely!”

Then Michael goes on to meditate on the fact that there can then be two of me and whether that makes the copy not-you. Here is what I said on that, in “On Being a Copy of Someone's Mind”:

On the assumption that experience comes from particles and fields known to physics (or of the same sort as those known to physics now), and that the emulation is truly faithful, there is nothing hidden. An em that is a copy of you will feel that it is a you. Of course, if you consented to the copying process, an em that is a copy of you will have that memory, which is likely to make it aware that there is now more than one of you. But that does NOT make it not-you.

You might object that the lack of physical continuity makes the em copy of you not-you. But our sense of physical continuity with our past selves is largely an illusion. There is substantial turnover in the particular particles in us. Similarity of memory—memory now being a superset of memory earlier, minus some forgetting—is the main thing that makes me think I am the same person as a particular human being earlier in time.

…

… after the copying event these two lines of conscious experience are isolated from one another as any two human beings are mentally isolated from one another. But these two consciousnesses that don’t have the same experience after the split are both me, with a full experience of continuity of consciousness from the past me. If one of these consciousnesses ends permanently, then one me ends but the other me continues. It is possible to both die and not die.

The fact that there can be many lines of subjectively continuous consciousness that are all me may seem strange, but it may be happening all the time anyway given the implication of quantum equations taken at face value that all kinds of quantum possibilities all happen. (This is the “Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics.”)

In other words, it may seem strange that there could be two of you, but that doesn’t make either of them not-you.

Michael points out that the digital world the copy lives in (if the copy is not embedded in a physical robot) will interact with the physical world we live in:

He may live in the cloud, with a simulated instead of a physical body, but his leverage on the real world would be as good as anyone else’s. We already live in a world where almost everything we do flows through cyberspace. We keep up with friends and family through text and Twitter, Facebook and Skype. We keep informed about the world through social media and internet news. Even our jobs, some of them at least, increasingly exist in an electronic space. As a university professor, for example, everything I do, including teaching lecture courses, writing articles and mentoring young scientists, could be done remotely, without my physical presence in a room.

The same could be said of many other jobs—librarian, CEO, novelist, artist, architect, member of Congress, President. So a digital afterlife, it seems to me, wouldn’t become a separate place, utopian or otherwise. Instead, it would become merely another sector of the world, inhabited by an ever-growing population of citizens just as professionally, socially and economically connected to social media as anyone else.

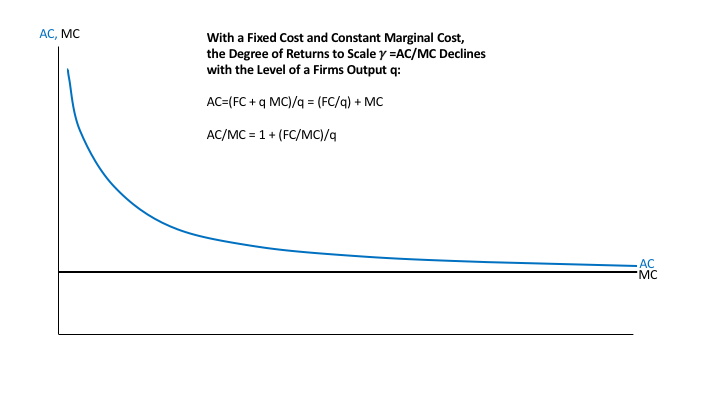

He goes on to think about whether ems, derived from copying of minds, would have a power advantage over flesh-and-blood humans, and goes on to wonder if a digital afterlife has the same kind of motivational consequences as telling people about heaven and hell. What he misses is Robin Hanson’s incisive economic analysis in the The Age of Em that, because of the low cost of copying and running ems, there could easily be trillions of ems and only billions of flesh-and-blood humans once copying of minds gets going. There could be many copies derived from a single flesh-and-blood human, but with different experiences after the copying event from the flesh-and-blood human. (There would be the most copies of those people who are the most productive.) I think Robin’s analysis is right. That means that ems would be by far the most common type of human being. Fortunately, they are likely to have a lot of affection for the flesh-and-blood human beings they were copied from and for other flesh-and-blood human beings they remember from their remembered from their past as flesh-and-blood human beings. (However, some ems might be copied from infants and spend almost all of their remembered life in cyberspace.)

Michael also writes about how brain emulation could make interstellar travel possible. He talks about many ems keeping each other company on an interstellar journey, but the equivalent of suspended animation is a breeze for for ems, so there is no need for ems to be awake during the journey at all. Having many backups of each type of em can make the journey safer, as well. The other thing that makes interstellar travel easier is that, upon arrival in another solar system or other faraway destination, when physical action is necessary, the robots some of the ems are embedded in to do those actions can be quite small.

But while interstellar travel becomes much easier with ems, Robin Hanson argues that the bulk of em history would take place before ems had a chance to get to other solar systems: it is likely to be easy and economically advantageous to speed up many ems to a thousand or even a million times the speed of flesh-and-blood human beings. At those speeds, the time required for interstellar travel seems much longer. Ems would want to go to the stars for the adventure and for the honor of being founders and progenitors in those new environments, but in terms of subjective time, a huge amount of time would have passed for the ems back home on Earth before any report from the interstellar travelers could ever be received.

Robin Hanson argues that, while many things would be strange to us in The Age of Em, that most ems would think “It’s good to be an em.” (Of course, their word for it would likely be different from “em.”) I agree. I think few ems would want to be physical human beings living in our age. Just as from our perspective now (if enlightened by a reasonably accurate knowledge of history), the olden days will be the bad old days. I, for one, would love to experience The Age of Em as an em. It opens up so many possibilities for life!

I know that an accurate copy of my mind would feel it was me, and I, the flesh-and-blood Miles, consider any such being that comes to exist to be me. In Robin’s economic analysis, the easy of copying ems leads to stiff competition among workers, so even if a copy of me were there in The Age of Em, I wouldn’t expect there to be many copies of me. I very much doubt that I would be among the select few who had billions of copies, or even a thousand copies. But I figure that at worst, a handful of copies could make a living as guinea pigs for social science research, where diversity of human beings subjects come from makes things interesting. And if the interest rates in The Age of Em are as high as Robin thinks they would be, by strenuous saving, the ems that are me might be able to save up enough money after a time or working in order to not have to work any more.