Susan Athey and Michael Luca: Economists (and Economics) in Tech Companies →

This is a pdf link to Susan and Michael’s Journal of Economic Perspectives article.

Larry Summers Says the Fed Should Move Fast to Cut Rates

The European Central Bank and the Reserve Bank of Australia have announced more monetary stimulus. Larry Summers says the Fed should follow suit, in his latest Washington Post op-ed:

The best way to take out recession or slowdown insurance would be for the Fed to cut interest rates by 50 basis points over the summer and by more, if necessary, in the fall. A serious recession anytime in the next few years would encourage populism and polarization at home, and reduce American influence and strength in the world as well as damaging the global economy. It is clear in retrospect that the Fed was too slow in responding to gathering storms during 2008 as the Great Recession took hold and in 2000 when the Internet bubble collapsed.

I make the point in “Next Generation Monetary Policy” that most central banks act too slowly in general: they should move interest rates faster and further, being quickly ready to reverse course so they don’t have to be afraid of overshooting.

Larry Summers is doing more than saying the Fed should move fast in general. He is arguing for a rate cut as insurance. Larry gives three key arguments. One is that the economy we are seeing now is what we get when the markets indicate that they are expecting rate cuts. The economy conditional on no rate cuts is worse than what we see. Another argument is that inflation expectations are not convinced that the Fed is serious about its 2% inflation target. In the last few months, Fed officials are being crystal clear in their words that 2% is intended to be a symmetric target. For example, from the Wall Street Journal article “Low-Inflation Trap That Ensnared Japan and Europe Worries Fed” by Nick Timiraos

“We’re trying to think of ways of making that inflation 2% target highly credible, so that inflation averages around 2%, rather than only averaging 2% in good times and then averaging way less than that in bad times,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said in February.

But the markets are brushing that off in their long-run inflation predictions. Larry points out:

… market expectations as reflected in Treasury index bonds are for inflation on the Fed’s preferred measure to remain in the 1.5 range even over a 30-year horizon and to be even lower over shorter horizons.

One can argue over the inflation target the Fed should set, but whatever they say the target is, if markets don’t believe them, that is a problem.

Larry’s other argument is that we have to nip any potential recession in the bud because the Fed may be slow to use deep negative interest rates:

… the Fed normally cuts rates by a cumulative 5 percentage points in response to recession, and with rates now below 2.5 percent there is nothing approaching that amount available. Allowing a recession with inadequate firepower to confront it risks “Japanification” — a situation where interest rates are permanently pinned at zero and deflationary pressures take hold. The Fed will be able to do too little in combating the next recession, so it is especially important that it’s not too late.

I agree. Until I can trust that central banks will, in fact, use the kind of vigorous negative interest rate policies that Ruchir Agarwal and I lay out in our IMF Working Paper “Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide,” I want them to avoid getting into a situation where they would need to do so to get a good outcome. Every year that passes is likely to make it seem easier for central banks to implement vigorous negative interest rate policies. If we can just avoid a serious recession in the meantime … (I am very eager for central banks to implement alternative paper currency policies at a very small dosage—say minus 5 basis points for the effective nominal rate of return on paper currency for a year or so) to demonstrate that they can, and to work out technical details. But I would be glad if the need to use negative interest rate policies in a big way—for example, minus 5 percentage points—can be put off for a while longer.)

Larry Summers was one of my professors at Harvard. I have known him a long time. I have talked to him on more than one occasion about negative interest rate policy. He understands the ideas well, and has them in his own view of contingency plans. (See “Peter Sands and Larry Summers Say Deep Negative Interest Rates Are Feasible from a Technical Point of View.”)

Competition from Generic Insulin Would Do a Lot to Reduce Medical Costs; But Reducing the Incidence of Type II Diabetes by Changes in the American Diet Would Do Much More

The social welfare benefits from improving the American diet (and the diet for most other countries) are large. One of the most important diseases fostered by a bad diet is Type II diabetes. In the article shown above, “Biohackers With Diabetes Are Making Their Own Insulin” Dana G. Smith gives this figure:

Diabetes has become the most expensive disease in the United States, reaching $327 billion a year in health care costs, $15 billion of which comes from insulin.

Dana explains the two forms of diabetes this way:

Insulin enables cells in the body to use glucose circulating in the blood as fuel. People with Type 1 diabetes don’t produce enough insulin, while people with Type 2 diabetes have become resistant to it. Without sufficient insulin, people experience high blood sugar, or hyperglycemia, which, over the long term, can cause heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and nerve damage. In severe cases of insulin insufficiency, ketoacidosis sets in, where the liver releases too many ketones into the blood, turning the blood acidic and potentially ending in death.

Although Type I diabetes may be fostered by feeding the wrong type of cow’s milk to infants (see “Exorcising the Devil in the Milk,”and “How Important is A1 Milk Protein as a Public Health Issue) I want to focus on Type II diabetes.

Since insulin’s job is to tell cells to take up sugar from the bloodstream, the more sugar enters the bloodstream, the harder insulin’s job is. The harder insulin’s job is, the more insulin has to be produced. And when a lot of insulin is produced, the cells that are being asked to take up sugar start to turn a partially deaf ear to the insulin—the phenomenon of insulin resistance. Since letting too much sugar remain in the bloodstream is very bad news, if cells become partially deaf to insulin, more insulin is produced in order to more loudly tell cells to take up insulin from the bloodstream, continuing the vicious cycle, unless something changes in the diet. At some point, if the vicious cycle continues to get worse, the resistance of cells to insulin outstrips the ability of the body to make insulin. That is what Type II diabetes is: insulin resistance so strong that bodily insulin production loses the race. Then the usual treatment is to inject insulin as a drug in order to shout even louder to cells to take up blood sugar.

But there is another way to treat diabetes once any acute emergency is taken care of: to change one’s diet to put less sugar in the bloodstream in the first place. Then, even with insulin resistance, the need for insulin is lessened. If blood sugar never gets that high to begin with, then modest levels of insulin will be enough to keep blood sugar at a reasonable level. What is even better, there is hope that the vicious cycle can be reversed into a virtuous circle, in which less insulin makes it so cells listen harder to the insulin that is produced. That is, there is hope the insulin resistance can be partly reversed if food-driven insulin production is reduced.

In addition, to the extent one eats in a way that drives up blood sugar less, less insulin is needed—whether produced by the body or injected—to keep blood sugar under control. This approach of using dietary changes to keep the need for insulin low is the approach of diabetes specialist Jason Fung, whose book The Obesity Code is featured in “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon” and "Five Books That Have Changed My Life."

Which foods drive high insulin production and thereby incur the risk of insulin resistance? I address that question in “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.” The insulin index directly measures food-drive insulin production. It is highly correlated with the glycemic index, which measures what foods drive up blood sugar, that I discuss in “Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index.” But there are some differences between the insulin index and the glycemic index, as I discuss in “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet.” Notably, some kinds of meat lead the body to produce substantial amounts of insulin.

So far in this post I have emphasized the role of excessive food-driven insulin production as something that can lead to Type II diabetes. But there is more. When sugar is taken up out of the blood, where does it go? Some goes to muscles. But some of the blood sugar typically goes to fat cells to be turned into body fat. So the very moderation of food-driven insulin production that can help ward off Type II diabetes can also help ward off obesity.

As long as people continue to get either Type I or Type II diabetes, it is shameful that the drug companies are keeping insulin prices so high by various strategies. It is possible what they are doing is illegal. Dana writes:

There are currently several lawsuits accusing the three drug companies of price fixing. One class action complaint claims Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk raised the list price of insulin in lockstep over the last 20 years, stating that the companies have been “unlawfully inflating the benchmark prices of rapid- and long-acting analog insulin drugs,” and placing them in violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.

But the production of generic insulin would only affect the $15 billion spend on insulin annually in the US, not the other $312 billion spent annually on other US diabetes-related health-care costs. And the production of generic insulin won’t do much to reduce the enormous nonfinancial suffering caused by diabetes. By contrast, changing the American diet could do a lot to reduce that $312 billion per year on other diabetes-related health care costs and the nonfinancial suffering attendant upon diabetes.

Unlike some nutrition experts, I don’t think the bad American diet is all about companies and culture pulling people away from clearly articulated principles of healthy eating. I don’t think the principles of healthy eating are articulated that well at all to the general public. In “Crafting Simple, Accurate Messages about Complex Problems” I write the following (and in square brackets I extend my statement to diabetes):

I believe that fighting obesity [and preventing Type II diabetes] requires more focused advice. Not “Do everything right, and here is the long list.” Instead, start with one action: go off sugar. I give some advice for that in “Letting Go of Sugar.” Don’t worry about anything else in the area of diet and health until you have accomplished that. After that, you can see where to go next in “4 Propositions on Weight Loss.” And if that all becomes old hat, then I recommend a reading program. I hope my blog posts are of some help, but those blog posts also point to some useful books to read. (To summarize, see “3 Achievable Resolutions for Weight Loss.”)

I list other blog posts about diet and health below. If you are interested in diabetes and insulin, use control-f (or option-f) to search for the word “insulin” or “diabetes” on this page. To go beyond that, put “insulin” or “diabetes” in the blog search box at the top of the webpage. But if you do that, you’ll get a large fraction of all the posts below: insulin is central to my view of diet and health.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography. I defend the ability of economists like me to make a contribution to understanding diet and health in “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’” and “Crafting Simple, Accurate Messages about Complex Problems.”

John Locke: The Obligation to Obey the Law Does Not Apply to Laws Promulgated by Invaders and Usurpers Who Do Not Have the Consent of the Governed

If one regards the Witenagemot as the legitimate 11th century body to decide who the King of England should be in cases of contested succession, then William the Conqueror was a usurper. But I’ll bet John Locke regarded many of the successors to William the Conqueror as legitimate rulers. How can that be? The key is that anyone who ascended to the throne from a power politics point of view as the successor to a usurper has the opportunity to make their case to the people to become a ruler by the consent of the governed. Back then, this was not always done by submitting to an election, but still involved trying to appeal to the people. For example, Queen Elizabeth I made many efforts to appeal to the people for support and willingness to be governed by her.

The way John Locke frames things in Chapter XIX of his 2d Treatise on Government: Of Civil Government, “Of the Dissolution of Government” is that both invasion and usurpation return people to a state of nature in their obligations. Then they have the right to decide on whether they agree with a particular proposal for a new government with a new ruler:

§. 211. HE that will with any clearness speak of the dissolution of government, ought in the first place to distinguish between the dissolution of the society and the dissolution of the government. That which makes the community, and brings men out of the loose state of nature, into one politic society, is the agreement which every one has with the rest to incorporate, and act as one body, and so be one distinct commonwealth. The usual, and almost only way whereby this union is dissolved, is the inroad of foreign force making a conquest upon them: for in that case, (not being able to maintain and support themselves, as one entire and independent body) the union belonging to that body which consisted therein, must necessarily cease, and so every one return to the state he was in before, with a liberty to shift for himself, and provide for his own safety, as he thinks fit, in some other society. Whenever the society is dissolved, it is certain the government of that society cannot remain. Thus conquerors swords often cut up governments by the roots, and mangle societies to pieces, separating the subdued or scattered multitude from the protection of, and dependence on, that society, which ought to have preserved them from violence. The world is too well instructed in, and too forward to allow of, this way of dissolving of governments, to need any more to be said of it; and there wants not much argument to prove, that where the society is dissolved, the government cannot remain; that being as impossible, as for the frame of an house to subsist when the materials of it are scattered and dissipated by a whirlwind, or jumbled into a confused heap by an earthquake.

§. 212. Besides this overturning from without, governments are dissolved from within, First, When the legislative is altered. Civil society being a state of peace, amongst those who are of it, from whom the state of war is excluded by the umpirage which they have provided in their legislative, for the ending all differences that may arise amongst any of them, it is in their legislative, that the members of a commonwealth are united, and combined together into one coherent living body. This is the soul that gives form, life, and unity, to the commonwealth: from hence the several members have their mutual influence, sympathy and connexion: and therefore, when the legislative is broken, or dissolved, dissolution and death follows: for the essence and unity of the society consisting in having one will, the legislative, when once established by the majority, has the declaring, and as it were keeping of that will. The constitution of the legislative is the first and fundamental act of society, whereby provision is made for the continuation of their union, under the direction of persons, and bonds of laws, made by persons authorized thereunto, by the consent and appointment of the people, without which no one man, or number of men, amongst them, can have authority of making laws that shall be binding to the rest. When any one or more, shall take upon them to make laws, whom the people have not appointed so to do, they make laws without authority, which the people are not therefore bound to obey; by which means they come again to be out of subjection, and may constitute to themselves a new legislative, as they think best, being in full liberty to resist the force of those, who without authority would impose any thing upon them. Every one is at the disposure of his own will, when those who had, by the delegation of the society, the declaring of the public will, are excluded from it, and others usurp the place, who have no such authority or delegation.

The lack of obligation to obey laws promulgated by rulers who do not have the consent of the people is highly relevant in the situation in Venezuela, as of June 1, 2019: Nicolas Maduro, who has most of the army behind him, does not currently have the consent of the people in the sense of being able to win a free and fair election, which in addition to being an attractive principle in its own right, was the constitutionally established way of choosing a ruler. Many Venezuelans have therefore transferred their loyalty to Juan Guaidó, who has the consent of a large number of Venezuelans to be their ruler, as well as the diplomatic recognition from many other countries as a ruler chosen by a constitutional process, as least for an interim leading up to an election.

Having a dominant army at one’s command does not make one a legitimate ruler. The people must consent to one heading the government, or there is no legitimacy and no obligation to obey new laws.

To avoid anarchy, a good rule is that old laws, duly enacted by duly chosen rulers should still be obeyed while the struggle with invaders and usurpers is carried on. No one should feel they can commit murder unrelated to the struggle for freedom simply because a usurper is on the throne. And many crimes, such as rape, have no legitimate role in any struggle for freedom. It might be inconvenient that old, duly enacted laws may become somewhat outdated if the struggle for freedom continues on a long time before resolution. But even in those cases, leaning hard toward obeying old, duly-enacted laws is an important shield against anarchy.

For links to other John Locke posts, see these John Locke aggregator posts:

Mark Fontana, Stephen Lyman, Gourab Sarker, Douglas Padgett and Catherine MacLean: Using Machine Learning to Predict Outcomes for Joint Surgery →

Mark Fontana is a coauthor of mine (“Reconsidering Risk Aversion,” with Dan Benjamin as well). I was the chair of his dissertation committee at the University of Michigan. He finished his Economics PhD in just 3 and a half years. This paper, on which he is the lead author (note the non-alphabetical ordering), gives a nice example of the use of machine learning.

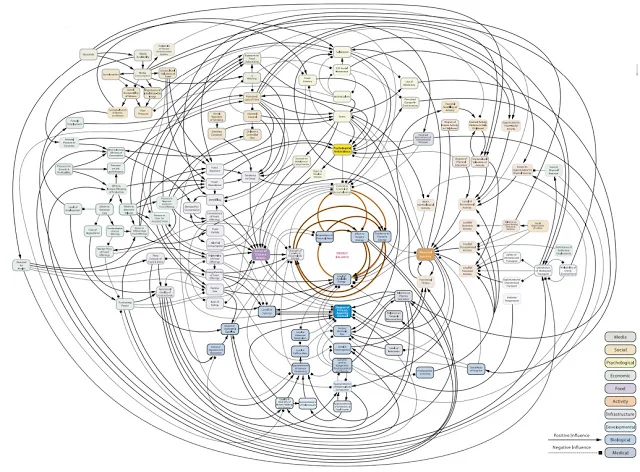

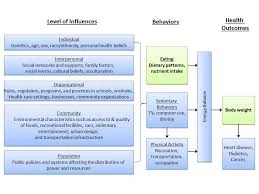

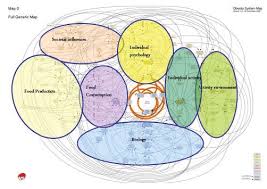

Crafting Simple, Accurate Messages about Complex Problems

image source. #1 image from googling “complexity of obesity”

image source. #2 image from googling “complexity of obesity”

image source. #3 image from googling “complexity of obesity”

Today is the 7th anniversary of this blog, "Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal." My first post, "What is a Supply-Side Liberal?" appeared on May 28, 2012. I have written an anniversary post every year since then:

Beyond family activities (within which my new role as a grandfather is a special joy), a large share of my efforts this past year have been devoted to three big projects that I believe in deeply as ways to make the world a better place:

Working toward the elimination of any lower bound on interest rates to restore the firepower of monetary policy. The big news in this area is my new IMF Working Paper with Ruchir Agarwal. See “Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball—Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide” or click on the “neg.rates” link right underneath my blog subtitle “A PARTISAN NONPARTISAN BLOG: CUTTING THROUGH CONFUSION SINCE 2012.”

Working out the principles for a national well-being index that could be credible as a full coequal to GDP with Dan Benjamin, Ori Heffetz, Kristen Cooper and our ace research assistant Tushar Kundu—with help from Rosie Li, who has mainly been working with Patrick Turley and me on the genetics of assortative mating. (See my happiness subblog for related posts.)

Fighting obesity, one diet and health post at a time. (See the links at the bottom of this post.)

Blogging about diet and health, I have gotten some pushback from those who are paid to be experts on diet and health, as you can see from “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’.” One of the more common criticisms is to say that issues of diet and health are complex, and I am oversimplifying. I think if you took the time to read the full set of blog posts, you would agree that I am allowing for a lot of complexity. But to make ideas understandable, it is important not to be juggling too many ideas at once. In “Brio in Blog Posts” I recommend that a blog post should have one central idea—otherwise it should be split into more than one blog post. I am afraid I don’t take my own advice, but that maxim has pulled me toward making blog posts more focused than if I didn’t have that maxim in mind.

I believe that fighting obesity requires more focused advice. Not “Do everything right, and here is the long list.” Instead, start with one action: go off sugar. I give some advice for that in “Letting Go of Sugar.” Don’t worry about anything else in the area of diet and health until you have accomplished that. After that, you can see where to go next in “4 Propositions on Weight Loss.” And if that all becomes old hat, then I recommend a reading program. I hope my blog posts are of some help, but those blog posts also point to some useful books to read. (To summarize, see “3 Achievable Resolutions for Weight Loss.”)

I am by nature a believer. I start by assuming that people are telling the truth or at least telling it as they see it. But being a blogger and interacting on Twitter has been for me a cold bath in reality: I have become more and more aware of people being dishonest or intellectually slovenly in ways they think can advance their careers. (For an example of intellectual slovenliness, see “Let's Set Half a Percent as the Standard for Statistical Significance.”) Let me get pointed in relation to diet and health: for some, it is all too easy to serve the interests of sugar companies by saying it is all complex and sugar is only a small part of the picture. If the statement that “Sugar is only a small part of the problem” is true at all, it is far from being proven. And given that almost everyone feels they need to agree that cutting back on sugar is a good idea, saying it is only a small part of the problem is the main available option for defending sugar.

In my view, saying something is complex can be consistent with crafting simple accurate messages about that issue. When price affects quantity and quantity affects price, one can say it is all complex—“the seamless web of history”—or one can use the analytical tools of supply and demand. It often is possible to cut through complexity to make useful points.

One of the strengths of economics is its emphasis on the craft of choosing which elements to put into a model and which elements to leave out. This is crucial for insight and understanding. It is crucial for insight and understanding because of the limitations of the human mind. (See “Cognitive Economics.”) Thinking that a map is unnecessary because we have the territory in front of us is usually a big mistake.

One of the strengths of blogging is that it is conducive to breaking complex issues into manageable pieces. Each post can tackle a different aspect of a complex issue, from a different angle. But hyperlinked together, those posts can respect the complexity without making everything totally opaque.

I hope that my tagline “cutting through confusion since 2012” isn’t an entirely false boast. If it isn’t entirely false, that gives me the motivation to continue blogging for the next seven years and beyond.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography. I defend the ability of economists like me to make a contribution to understanding diet and health in “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’.”

Ezra W. Zuckerman—On Genre: A Few More Tips to Academic Journal Article-Writers →

Above is a link to a pdf.

Disregard for truth as a Sign of a Totalitarian Impulse

The headline: “MFA confirms offensive remarks from patrons, bans two members.”

Link to the tweet above. Link to a more recent Boston Globe article about the incident.

I responded to Melissa McDaniel’s tweet above with these tweets:

It is dangerous to our society when finding out and verifying the truth is denigrated. Racism and sexism are real. Proving that they reared their ugly head in a particular instance is a valuable service in fighting them.

Let me say that in relation to sexual harassment and sexual abuse, a good Bayesian assessment of whether it occurred in a given instance requires an understanding of how high the base rates are. But we don't want to create strong incentives (now quite weak) for false accusation.

The temptation to set aside or denigrate truth in service of a cause is an old one. Many religions, believing that people’s eternal souls or the fate of the world were at stake, have subordinated ordinary garden variety small-t truth to what they considered a grander Truth. But as I said in “What is a Partisan Nonpartisan Blog?” I am with my best friend Kim Leavitt in believing

We are in trouble if we let our devotion to Truth get in the way of our devotion to truth.

In particular, those who show a disregard for truth in their eagerness to get particular results betray a certain controlling—and in the extreme—totalitarian impulse. Or to take another perspective, one time that deception and lying is justified is in wartime. But by that analogy, lying to me is a sign that the liar is my enemy. I would much rather make a judgment myself, knowing the truth, than let someone else make that judgment for me. Any argument that I am not able to make that judgment puts me at a lower rank than those who can be trusted to know the truth. In some contexts, such as national security or grand jury testimony, I am OK with being at a lower rank. But in regard to, say, making a judgment about, say, Brett Kavanaugh, as I did in “On Guilt by Association,” or Donald Trump, I would not be OK with the antidemocratic approach of saying only others could be trusted to see the evidence.

Trust but Verify: Bayes Rule. Let me explain my remarks about a Bayesian approach. Bayes’ Rule says that the probability P( ) that someone is guilty of, say, sexual abuse, given being accused, is

P(guilty given accused) = P(guilty) P(accused when guilty) /

P(guilty) P(accused when guilty) + P(innocent) P(accused when innocent)

The fact that sexual abuse is common makes P(guilty) high for the accused and non-accused combined. This “base right” that so many people are, in fact, guilty of sexual abuse makes it more likely that any particular person who is accused is, in fact, guilty. But something that can drag down the probability that any particular person is guilty when accused is if the probably of being accused even when innocent—P(accused when innocent)—is high. Currently, I think the probability of being accused of sexual abuse when innocent is only of moderate magnitude. (It becomes higher in custody battles and political battles where there is more to gain from a false accusation.) And the base rate of being innocent when including both the accused and non-accused—P(innocent)—is high. So if the fraction of innocent people who are accused ever were to become high, that would totally change the equation.

We currently have a system that asks for enough verification that the incentives to falsely accuse are kept in check. But if we ever stopped asking for verification, the number of false accusations could skyrocket. One cannot generalize from a small number of false accusations now to a small number of accusations in a future world where we stopped asking for verification (leaving the accuser unavenged or unhappy if verification cannot be found).

Conclusion. To me, confirming is a noble thing. We need to know what is true and what is not. Anyone who can help us in that regard is doing a good thing. (I talked about some of the key exceptions in my discussion of blackmail in “The Government and the Mob.”) Wherever public policy relies on concealment or deception, we should always be looking for alternative ways of achieving the end (assuming the end is worthwhile) that do not require concealment or deception.’

In the arena of truth, I feel that scientists—both natural and social scientists—have an extra responsibility to serve the truth. It makes me angry to ever see a scientist subvert truth for the sake of other ends—whether those ends are furthering a career or furthering a cause. Trying to turn this principle on myself, I wrote in “What is a Partisan Nonpartisan Blog?”

In a fractal recapitulation of the “team-loyalty versus unvarnished opinion on each issue” conflict, fidelity to the truth can sometimes hurt the overall thread of one’s argument on an issue. Here, fidelity to the truth has to come first. Let me list the legitimate excuses: (a) there is no duty to mention facts that seem to run against one’s argument that are actually unimportant and could easily be answered; (b) for clarity it is permissible to defer dealing with even important, widely-known facts until a commenter sets up the Q part of the Q&A; and (c) human language always deals in approximations, especially in short-form essays. But for a blogger who hopes to have the trust of readers, it is never OK to say something one knows to be false and misleading, even in the service of what one might think is a higher Truth.

I am also angry with anyone who says, in any context, that it isn’t important to verify the truth before rushing to judgment in any matter of consequence.

Related posts:

Teens are Too Suspicious for Anything But the Truth about Drugs to Work

Let's Set Half a Percent as the Standard for Statistical Significance

Martin Boileau: Even in Chaotic Times, Economics Helps Make Sense of the World →

This is the writeup of a very nice interview with my senior macro colleague at the University of Colorado Boulder, Martin Boileau. (I write here about my move to the University of Colorado Boulder after 29 years at the University of Michigan.)

Brian Flaxman—A Tale of Bipartisanship and Financial Interests: The Taxpayer First Act of 2019

Brian Flaxman

I am pleased to have another guest post from Brian Flaxman, a PhD student here at the University of Colorado Boulder. Brian’s first guest post here was “Yes! Economics Did Sway Obama Voters to Trump.” Below are Brian’s words:

On March 28 of this year, the Taxpayer’s First Act of 2019 was proposed and sent to the House Ways and Means Committee and Financial Services Committee. It made its way out of both committees and passed the House on April 9th. It was sponsored by Democratic Rep. John Lewis, and had 18 Democratic Cosponsors and 10 Republican Cosponsors. Among two of the cosponsors were head of the Ways and Means Committee Democratic Rep. Richard Neal, and the ranking Republican on the committee Rep. Kevin Brady, considered to be one of the architects of the controversial Tax Reform Bill passed at the end of 2017. In fact, there was such a large support for the bill, it was able to be passed with a voice vote rather than the standard role-call vote. This act of bipartisan support for the legislation may be seen by some as a rare moment in today’s political climate. However, the problematic nature of this legislation is a prime example of why bipartisanship should not be heralded in and of itself.

Many of the provisions in the bill are positive for the everyday tax payer, including the institution of an independent appeal process for taxpayer discrepancies that avoids litigation and creating several measures to crack down on IRS corruption. However, the bill continues indefinitely the IRS Free File program. This program, created in 2002 and set to expire in 2021, allows for low-income taxpayers to use private sector tax-filing software for little or no cost. However, this program also explicitly forbids the IRS from creating its own publicly available tax filing software. And permanently codifying the entire program also indefinitely prevents the IRS from producing a viable, cost-effective, competition-increasing alternative to privately available software. While bad for the average American, the tax preparation industry benefits from this measure significantly. It is therefore no surprise then that preventing the IRS from creating such software is a long time priority by the tax preparation industry.

If the Free File program was successful, the argument could be made that keeping it in place while continuing to ban the IRS from creating competing software is a tradeoff that ends up benefiting the American public. In practice though, the American public has seen minimal benefit as the program is massively underutilized. Only 3% of the taxpayers that qualify for the program (70% of the public is eligible) end up using the Free File program. According to estimates by Pro Publica, while the program has saved taxpayers $1.5 billion in 16 years, taxpayers eligible for the program spend an unnecessary $1 billion dollars per year on tax filing software. This is because tax-preparation companies have actively tried to minimize the usage of the program by obscuring its presence in two different ways. First, Intuit customer service representatives actively steer clients away from the Free File version to a basic free version and are told to mention the program only when specifically asked about the Free File program. This in many cases leads to eligible taxpayers unnecessarily paying for their tax preparation.

However, the main way they are able to obscure the presence of the program involves both their website’s design and intentional manipulation of search engine optimization. TurboTax’s main website does not contain the Free File version of their program called the “Freedom Version,” while barely mentioning its existence. In fact, one of the only mentions of the Free File version is hidden away in their FAQ, where they plainly admit that it is not on their main site.

However, on their main website where they advertise their list of products, TurboTax prominently displays a basic free version completely separate from the Free File of their program that handles some basic filings, but then upsells other services.

Source: TurboTax Website

And the lack of public knowledge about the program is furthered by manipulating search engine results by paying for ads. For example, a simple search of “IRS Free File Taxes” on Google will first bring up ads for the tax preparation companies, but are not the Free File versions. To find Intuit’s true Free File program, it takes a Google search of “TurboTax Freedom Edition.” Because of these deceptive practices, a class action lawsuit has been filed against both Intuit and H&R Block.

Given the failures of the program, it is no surprise that the program’s continuation has led to an immense backlash, one so large that the bill has stalled in the Senate. So why did the House of Representatives pass the legislation, and with such bipartisan support? Maybe it has something to do with the active lobbying and campaign donations that the tax preparation industry is a part of. The tax preparation lobby spent over $6.7 million in lobbying in 2018 alone. Furthermore, members of the two committees through which the bill passed through before making it to the House floor received many donations from the tax preparation lobby. The committee whose members received the most in contributions from both H&R block and Intuit in the 2018 election cycle was the Ways and Means committee. Members of the Ways and Means Committee received over $100 thousand dollars in contributions from the two companies’ combined. While Intuit did not contribute a large amount to members in the Financial Services Committee, H&R Block did, with them coming in second, and receiving over $60,000. It is important to note that these figures are from companies that only perform tax-preparation. Any financial firm that performs tax preparation would be negatively impacted by a public tax filing software, and many large diversified financial firms will regularly spend tens of millions of dollars on lobbying and donations in a single election cycle.

Given that the Republican Party has a more corporate-friendly agenda, it would be reasonable to assume that Republicans were the main beneficiaries of campaign donations. However, this is not the case. Democratic Ways and Means Committee members received $41,345 in total with the Republican members receiving $67,500. And when it comes to the over $60,000 donated to members of the Financial Services Committee, Democrats actually received more than Republicans, with a $35,565 to $27,500 split. Obviously, profit-maximizing firms are spending so much on lobby and campaign contributions because they seek a return on investment, which they almost certainly did with the Taxpayer First Act of 2019.

While the passage of the Taxpayer First Act is only a single piece of legislation that will not greatly impact the public in the grand scheme of things, it acts as a microcosm of the dysfunction with our political system. This bill is obviously detrimental to the average American, yet it was passed anyway after heavy political activity from corporate interests. It is quite difficult to view the massive spending by these corporate interests as anything other than a form of legalized bribery, and the public’s confidence in political institutions continues to erode. It also shows that while bipartisanship in Washington is alive and well, that is not positive in and of itself, because much of the time, the driving force behind the parties agreeing is based on the interests of their common donors and not on issues Americans of both parties agree on.

Sources:

H.R.1957 - Taxpayer First Act of 2019 (https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1957?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22taxpayer+first%22%5D%7D&s=3&r=1)

Open Secrets (https://www.opensecrets.org/)

Pro Publica: Here’s How TurboTax Just Tricked You Into Paying to File Your Taxes (https://www.propublica.org/article/turbotax-just-tricked-you-into-paying-to-file-your-taxes)

Pro Publica: Congress Is About to Ban the Government From Offering Free Online Tax Filing. Thank TurboTax. (https://www.propublica.org/article/congress-is-about-to-ban-the-government-from-offering-free-online-tax-filing-thank-turbotax

TurboTax Website: https://turbotax.intuit.com/personal-taxes/online/

Bad News for IV Estimation →

This is a post by Frank Diebold about a paper by Alwyn Young. Also see the followup post about a paper by Narayana Kocherlakota with a similar bottom line.

Critiquing `All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality with Low-Carbohydrate Diets' by Mohsen Mazidi, Niki Katsiki, Dimitri P. Mikhailidis, Naveed Sattar and Maciej Banach

I am fortunate to have free access to the full text of most medical and nutritional studies through the wonderful website for the University of Colorado Boulder’s Norlin library. So let me contribute to the nutritional debate by telling what I learned from digging into the full article “Lower carbohydrate diets and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study and pooling of prospective studies” behind the ungated distillation by the authors Mohsen Mazidi, Niki Katsiki, Dimitri P Mikhailidis, Naveed Sattar and Maciej Banach, which is supertitled “Higher risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality with low-carbohydrate diets.”

The authors divided people into four groups based on a score that gave “low carbohydrate diet” points for having a diet low in percentage of calories from carbohydrates, points for being high in percentage of calories from fat and points for being high in percentage of protein. The coefficients are not transparent. They write:

]Consumption of carbohydrates was scored from 10 (lowest consumption) to 0 (highest consumption), whereas protein and fat intake were scored from 0 (lowest consumption) to 10 (highest consumption).

A key point I want to emphasize is that they are not testing the seeming effects of a low-carb, high-fat diet, but the effects of a low-carb, high-fat and high-protein diet. In particular, their strongest results are for the fourth quartile, which has dramatically higher protein as well as dramatically higher fat than the other quartiles. They write:

Participants were stratified into quartiles, based on LCD score:

Q1: median LCD score of 12, 367 g carbohydrates/day, 77 g protein/day, 73 g fat/day [reference]

Q2: median LCD score of 15, 245 g carbohydrates/day, 69 g protein/day, 65 g fat/day

Q3: median LCD score of 18, 205 g carbohydrates/day, 72 g protein/day, 70 g fat/day

Q4: median LCD score of 21, 214 g carbohydrates/day, 103 g protein/day, 105 g fat/day

The distillation has a striking graph:

The colored lines with the small circles show the point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for risk ratios implied by the regression coefficients in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards model. The risk ratios are for each of the other quartiles compared to the first quartile, which is very high carb.

The Possible Dangers of a High-Protein Diet. I am not at all surprised that the high-protein diet indicated by the red line might be dangerous. I have written about the possible danger that too much protein might promote cancer in these two blog posts:

The results in the study by Mohsen Mazidi, Niki Katsiki, Dimitri P Mikhailidis, Naveed Sattar and Maciej Banach raises the question of whether protein creates a risk for stroke and heart disease as well. Unfortunately, it is hard to distinguish in an observational study like this between the effects of dietary fat and the effects of dietary protein since dietary fat and dietary protein are highly correlated. My suspicion, partly coming from just my love of being contrarian, is that dietary protein has too positive a reputation and dietary fat too negative a reputation. That is, I think that dietary fat is often getting blamed for the harm caused by dietary protein, especially animal protein.

Controlling for Calories Consumed Changes the Interpretation Dramatically, in a Way the Authors Do Not Recognize or Acknowledge. Leaving the fourth quartile results undisputed as a possible warning about high-protein diets (with other besides me free to dispute them), let’s turn to the light and dark blue lines showing the estimated risk ratios for the second and third quartiles relative to the first. If you look carefully at what I have copied out above, you can see something strange. The second and third quartiles have a median consumption of all three macronutrients that is lower than in the first quartile. Why would eating less fat, less protein and less carbs lead to higher mortality? It isn’t as if these folks are starving. The answer is that the multivariable Cox model controls for total number of calories consumed. The authors write in the full paper:

… we had two different models: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, education, marital status, poverty to income ratio, total energy intake, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption; and Model 2 adjustment for Model 1 plus body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, hypertension, serum cholesterol and diabetes.

To my mind, this doesn’t give a low-carbohydrate diet a fair chance. The main harm I see from carbohydrates (especially easily-digested carbohydrates) is that they make you hungry so you eat more total calories. That story certainly matches what is happening with the median consumption numbers in the first quartile: carbohydrate grams are much higher in the first quartile without fat or protein grams being any lower—indeed, fat and protein grams are somewhat higher. If most of the harm of a high-carb diet is that people end up eating too much and the benefit of a low-carb diet is that people end up eating less, controlling for total calorie consumption in the regression slices out one of the main mechanisms through which low-carb diets are helpful. Note that Model 2 goes even further in this direction, by controlling for body mass index, which thereby insures that any benefit of a low-carb diet that operates through weight loss is sliced out. And without other analyses, that means that effects of low-carb diets that operate through reducing appetite and through weight loss are ignored.

It is important to have a multivariable model, because the first quartile has lower alcohol consumption and less smoking, but controlling for something that might be a key intermediate causal variable totally changes the interpretation of the results. Let me point to one specific possibility to make the issue more vivid. One type of low-carb diet that would still leave me hungry so that I’d be likely to eat a lot would be cutting back drastically on vegetables and whole grains while keeping my sugar consumption at full throttle. So when the regression looks at people whose carb consumption is low but who are eating a lot of calories, it might be focusing on people whose carb consumption is almost entirely unhealthy carbs that keep appetite up, with the healthy carbs cut out.

The Author’s Meta-Analysis of Other Studies also Makes High-Protein Look Bad. In addition to their own regressions, the authors to a meta-analysis of regressions by other authors. In their report on the meta-analysis, they appropriately emphasize the “high-protein” aspect of the story:

Low-carbohydrate/high protein diet mortality

There was a significant association between LC/HP and overall mortality [RR 1.16, 1.07–1.26, P < 0.001, n = 5 studies, (no heterogeneity, I2 = 17.6, P = 0.825), Supplementary material online, Figure S2], as well as a positive correlation between LC/HP and CVD mortality (RR 1.35, 1.07–1.69, P < 0.001, n = 5 studies, Supplementary material online, Figure S3), with minimal evidence of heterogeneity (I2 = 21.5, P = 0.736). In contrast, a significant trend between LC/HP and cancer mortality was observed (RR 1.03, 0.99–1.07, P = 0.084, n = 3 studies, Supplementary material online, Figure S4), but with modest of heterogeneity, (I2= 57.3, P = 0.036).

Conclusion. A general point is that authors in the nutrition area are not always good at interpreting their own results. Economists are rewarded professionally for finding the flaws in other researchers’ regression designs and interpretations. So we get good at finding such chinks in the armor. I think everyone would get a much more accurate sense of what the evidence about nutrition really says if more economists got involved in thinking about that evidence. I could personally be mistaken quite easily. But if many economists were scrutinizing nutrition studies, collectively they would add a lot to understanding in this area.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography. I defend the ability of economists like me to make a contribution to understanding diet and health in “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’.”