This is the text for my June 9, 2013 Unitarian-Universalist sermon to the Community Unitarian-Universalists in Brighton, Michigan. You can see the video here.

This is the fourth Unitarian-Universalist sermon I have posted. The others are

This is the first sermon I have given that I have known in advance I would post. I wrote it with my online readers in mind as well as the Unitarian Universalists in Brighton.

Abstract: Many of us have a strong desire to do something big, both because we want to make the world a better place and because of ambition. That desire can get twisted in various ways, but it is also behind much of the progress in the world. How can we harness ambition for good, and link it to genuine visions of a better world?

Human beings are roiling puddles of emotions, not all of them pretty. For example, the Medieval Pope Gregory I listed seven deadly sins: wrath, greed, sloth, pride, lust, envy, and gluttony. And yet we roiling puddles of emotions sometimes set out to make the world a better place. How can entities so imperfect accomplish anything good? I want to argue that if we turn our emotions, even the ugly ones, into sources of energy for action—while putting careful guardrails on our actions to try to ensure that we do good rather than harm—then together we can save the world.

Economists like me think a lot about the fact that living standards and lifespans are dramatically higher than they were as recently as a century ago. And Steven Pinker argues that there is a lot less violence than in the past in his book “The Better Angels of Our Nature.” But it is clear the world still needs saving. Many live in poverty. Many live under oppressive dictatorships. There are a thousand reasons why and ways in which people are mistreated, sometimes even by their own families. The possibilities of a nuclear holocaust fostered by nuclear proliferation or catastrophic climate change fostered by the burning of coal and other fossil fuels cast monstrous shadows over the future. And in a very immediate way, the global economic slump in the last few years has shaken people’s faith in governments and economies.

A year ago, I started a blog, “Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal,” out of a mixture of raw ambition, desire for self-expression, duty, and hope. Sometimes duty keeps me up late at night, but it is raw ambition that makes me wake up too early in the morning so that I slip further and further behind in my sleep. And sometimes, alongside that raw ambition, I find anger driving my writing, when I see someone who is relatively influential saying things that I think not just off-base, but potentially destructive. (See for example “Contra John Taylor" and ”Even Economists Need Lessons in Quantitative Easing, Bernanke Style.“) Whatever redeeming social value there is to what I write when in that state does not take away the fact that the experience is one of giving vent to anger.

The Christian tradition emphasizes the motivations someone has in doing any particular action. At one level, this makes a lot of sense. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said:

But if thine eye be evil, thy whole body shall be full of darkness. If therefore the light that is in thee be darkness, how great is that darkness! (Matthew 6:22)

and

Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves. Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles? Even so every good tree bringeth forth good fruit; but a corrupt tree bringeth forth evil fruit. A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit, neither can a corrupt tree bring forth good fruit. (Matthew, 7:15-18)

If someone’s overall objective is evil or self-serving, the only way what they do will have a good effect on the world is if all their attempts to get their way by harming others are forestalled by careful social engineering. It is exactly such social engineering to prevent people from stealing, deceiving, or threatening violence that yields the good results from free markets that Adam Smith talks about in The Wealth of Nations—the book that got modern economics off the ground. And even then, social pressure to favor those in the old boys’ club can deprive others of the full benefits of the free market.

But what if there is a bumper-car derby in one’s heart between an overall desire to do good and uglier emotions such as wrath, greed, sloth, pride, lust, envy, and gluttony? Are all one’s efforts polluted?

The simple answer to this question is that when motives are impure, the danger of a bad result is great, but that careful checks and balances can sometimes yield a good result from imperfect soil. One of the best examples is Martin Luther King. He committed serial adultery and plagiarized an important piece of his Ph.D. dissertation in a way that makes no sense unless he was subject to lust, greed, sloth, pride and envy. But for the Civil Rights Movement, the main danger was from unchecked anger, and the principle of nonviolence that Martin Luther King championed set up a key guardrail for the effects of anger that was crucial to the degree of racial reconciliation that he and his coworkers wrought in the world.

On the other side of the question, suppose one’s motives are pure as the driven snow. Is a good result inevitable?

St. Bernard of Clairvaux gave the answer when he said “The road to hell is paved with good intentions,” or in another loose translation: “Hell is full of good meanings, but heaven is full of good works.” There are at least two gaps between good intentions and good works. One is inaction; the other is lack of the knowledge and wisdom to take a good objective and turn it into good policy. The law of unintended consequences is particularly powerful in economics. It is not easy understanding complex social systems. And doing the wrong thing for the right reason reliably yields the wrong result. At least in economics, the history of thought and the things we have tried in the past have given us some hard-won expertise. The law of unintended consequences may operate even more powerfully in some other area of social change, but where our understanding of cause and effect is even less than our understanding of economics, we have little choice but to try what seems best and see what happens, hoping to learn from our mistakes.

How to go about saving the world: Let’s say that despite all the difficulties, you want to save the world. That is, you want to make things better and make a difference. How should you proceed?

A. Find a vision: First you need to decide what your goal is. What is your vision of how the world should be? How does the world fall short? What kinds of outcomes would make you feel the world was getting closer to that vision? A few years back, I argued that Unitarian Universalists should make sharing our individual visions of what a wonderful world would look like a regular part of our religious practice, just as Unitarian Universalists have made sharing our individual beliefs—our credos—a regular part of our religious practice.

One bit of training I found very useful in finding and expressing a vision was Landmark Education’s personal growth and leadership courses. These courses are a bit of applied philosophy with an Existentialist twist, but touch on both religious and psychological issues. They go back to Werner Erhard’s est, but are the kinder, gentler version. They take place typically in a large group setting of maybe 150 people. With a group of that size, it is easy for the leader of the class to get volunteers to set out problems from their lives that they would like to solve. I found these courses very powerful and helpful, and recommended them to many of my friends and family at the time I was doing them. I recommend them to this day even though I have not personally done any courses since the mid-90’s. Most of my friends and family also had a good experience, though a few were turned off by hard-sell and the forcefulness of some of those running the courses. One of the most impressive outcomes from the Landmark course is the frequency with which people are able to let go of longstanding grudges and forgive others in their lives as a result of the courses.

Let me give a brief summary of what I learned. In the first course, the nature of our daily lives is dissected into the grudges, the self-pity and the serviceable but overused strategies that cover over our underlying insecurity. The Existential twist is that while all of this is meaningless, it is OK that it is meaningless, since that gives each of us the opportunity to choose what we want our lives to mean—our individual visions of a good life and a wonderful world. The later courses talk about how to articulate that vision, how to work backward from that vision to see what needs to be done now, and how to express that vision to others and involve them in helping to make it a reality.

In the Landmark courses, an ingenious screening mechanism along the lines of Kant’s categorical imperative is used to ensure that a vision is not too self-serving. Kant wrote:

Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.

In the Landmark courses, a typical stem for a vision or personal mission statement is

“I am the possibility of all people …”

The other bit of quality control is that the rest of the people in the class vote on whether they think the vision speaks to them as well, though of course it is likely to have a special personal resonance to the one declaring the vision. What I articulated in the end was this:

I am the possibility of

- all people being empowered by math and other tools of understanding;

- fun;

- adventure into the unknown;

- human connection and justice and welfare;

- profound relationship;

- all people being joined together in discovery and wonder.

A declaration like that is a good start on a vision.

B. Make sure you know what you are doing. Here, one of the big dangers is that there are many people who will want to mislead you about what will really make a difference in the world. Many companies try to increase sales by convincing people that buying their product will save the world. And many organizations try to increase membership by convincing people that joining and supporting their organization will save the world. In some cases, it may be that buying the product or joining and supporting the organization will in fact help to save the world, but it pays to be skeptical.

In addition to cases like this where a bit of cynicism can actually be protective, there are many cases where someone you have chosen as a guide, though quite sincere, doesn’t know what he or she is talking about. In practice, there is no good substitute for trying to figure things out for yourself enough so that you can begin to separate the wheat from the chaff. It takes a little bit of expertise of your own to distinguish the true experts from the posers. And even then, you have to combine the facts and understanding you get from them with your own vision. For example, the balance you want to strike between symbolism and substance might be different than the balance struck by the expert you trust.

C. Stay on track. But finding a vision and making sure you know what you are doing are only the beginning. You need to set up guardrails so that your personal temptations and failings don’t distort or destroy the good you hope to do. Sloth could easily stop you in your tracks. Greed could lead you to sell out. Pride and envy could make you see someone who could be your biggest ally as if they were your biggest enemy. Lust, unchecked, can derail almost anyone’s efforts, as it derailed a substantial portion of what Bill Clinton could have otherwise done as president. Wrath can easily steer you wrong. And gluttony can lead to an early death that cuts everything short.

Avoiding the seven deadly sins isn’t enough. Here are some other principled guardrails.

1. The Basics: First, follow basic rules such as trying to give everyone a fair hearing, keeping your promises, giving credit where credit is due, and avoiding gratuitous nastiness.

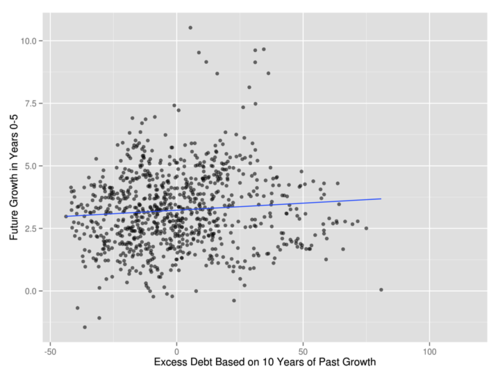

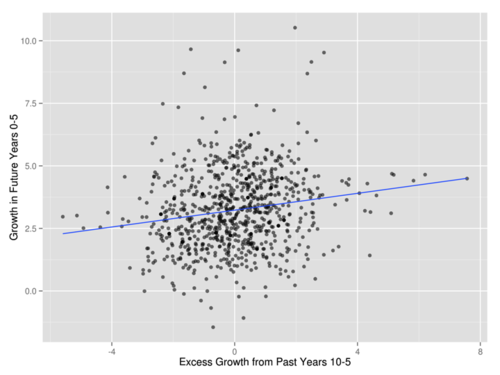

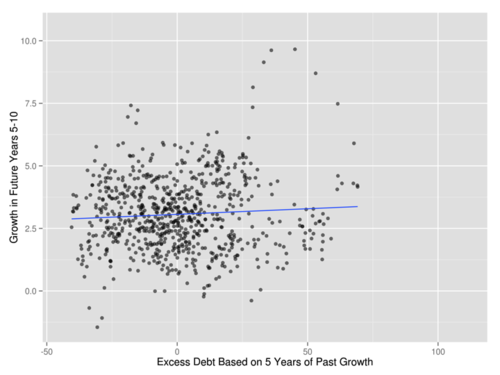

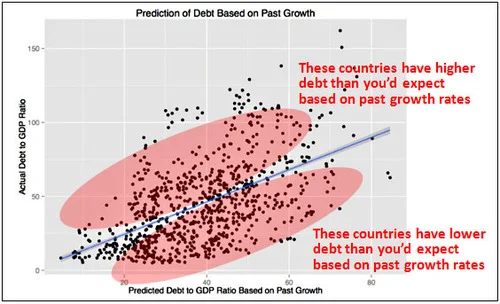

I say “avoiding gratuitous nastiness” because I can understand why people sometimes feel that getting the job done requires sharp words, satire of opponents, or vigorous attacks. Fareed Zakaria, in a CNN interview with Paul Krugman about his spat with Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff about their claim that government debt leads to lower economic growth, asked Paul this:

Fareed Zakaria: Are you surprised how personal this has gotten?

Paul Krugman: No, the stakes are high. I guess from my point of view, they went pretty far out on a limb with work which is far weaker than everything else in their careers. And, unfortunately, that became what they’re known for. And then if you said, well, this is really bad work and this had a deleterious effect on policy, which I believe to be the truth, how can it not be personal?

Let me say it, by the way – who cares, right? I mean who cares about my feelings or Carmen Reinhart’s feelings or Ken Rogoff’s feelings? We’re having a global economic crisis which is not over, which we have handled abysmally. We have massive long-term unemployment in the United States. We have massive youth unemployment in Southern Europe.

I don’t think the question of how civil a bunch of comfortable academic economists who went to MIT in the mid-1970s…I don’t think that matters at all compared to the question of the substantive issues and are we doing this wrong, which I think we are.

Quite apart from the substance of Paul’s debate with Carmen and Ken, I have to agree with Paul that when issues are important enough there can be a danger of being too nice to get down to brass tacks. However, being harsh also frays the social fabric in important ways. So it is a difficult judgment call.

2. The Truth. Second, don’t ever abandon the truth, even if it doesn’t seem to suit your purpose. There are two levels to honoring the truth:

- frankly recognizing and admitting facts that go contrary to the case you are trying to make, and

- giving your honest best judgment about an issue even if it puts you at odds with your own group.

One reason to honor the truth is that, in the end, it is hard to be genuinely effective at fooling others except by fooling yourself. And fooling yourself is one of the easiest ways to cloud your vision of a better world.

3. Equality. Third, treat everyone as an equal. Treat ordinary people with dignity and they will become extraordinary. Treat the high and mighty as human, and they won’t be able to hypnotize you by the trappings of power with which they surround themselves.

4. Perspective. Fourth, keep perspective. Among all the tasks that need to be accomplished to get the world a bit closer to your vision, some are more important than others. But it is easy to forget what is most important to the overall goal as the realities of overcoming obstacles narrows focus to one particular task at hand. Usually, the only way to keep perspective is keep returning to the original vision you identified as your goal, and again think through how each task fits into that larger goal.

5. Balance. Finally, in trying to save the world, don’t forget the rest of your life. In his first letter to Timothy (1 Timothy 5:18), the Apostle Paul quotes the Torah saying “Do not muzzle an ox while it is treading out the grain” and “the worker deserves his wages.” If you are trying to save the world you deserve to have enough of a life besides that to recharge and replenish yourself. And you have duties to those close to you—your family and friends—as well as to those far away. And should you forget the other parts of your life, that neglect will take a toll on the grand cause you have set for yourself, whether by lack of sleep, lack of serendipitous input into your thinking, or the distractions that come from troubled personal relationships. It is far better to bring others around to your vision, or get them started in finding their own, than to burn yourself out trying to save the world on your own.

As one would expect from a principle of balance, the demands of balance are not absolute. Sometimes sacrifices are necessary. But don’t be too quick to assume that the part of your overarching effort that is at hand is so important as to be worth sacrificing the parts of your overarching effort that are yet to come, that you haven’t yet even imagined. For most who set out to save the world, setting a pace that can last a lifetime and keeping to it will yield more fruit than going out in one blaze of glory. And time may bring yet greater wisdom.

Summary. To sum up, if you want to save the world, find a vision, make sure you know what you are doing, and stay on track by

- being wary of the seven deadly sins,

- following the basics of fair play and decency,

- honoring the truth,

- treating everyone as an equal,

- keeping perspective and

- maintaining balance.

One more thing that can make saving the world a rewarding experience–instead of a dreary one–is to be cheerful. The efforts of our ancestors to save the world have succeeded to a remarkable degree, giving us a much better world to live in than they had. There is no reason to doubt that our best efforts, too, will succeed in making the world our children and grandchildren live in better still.

Note: I have collected links to some of my "save-the-world” posts in “The Overton Window” and “Within the Overton Window.”