Defending Jordan Peterson

Many people feel that the words they say are as much a part of their identity as their sexuality. We should go a long way to give people freedom of expression in both areas.

Jordan Peterson got in trouble with Twitter for a tweet saying:

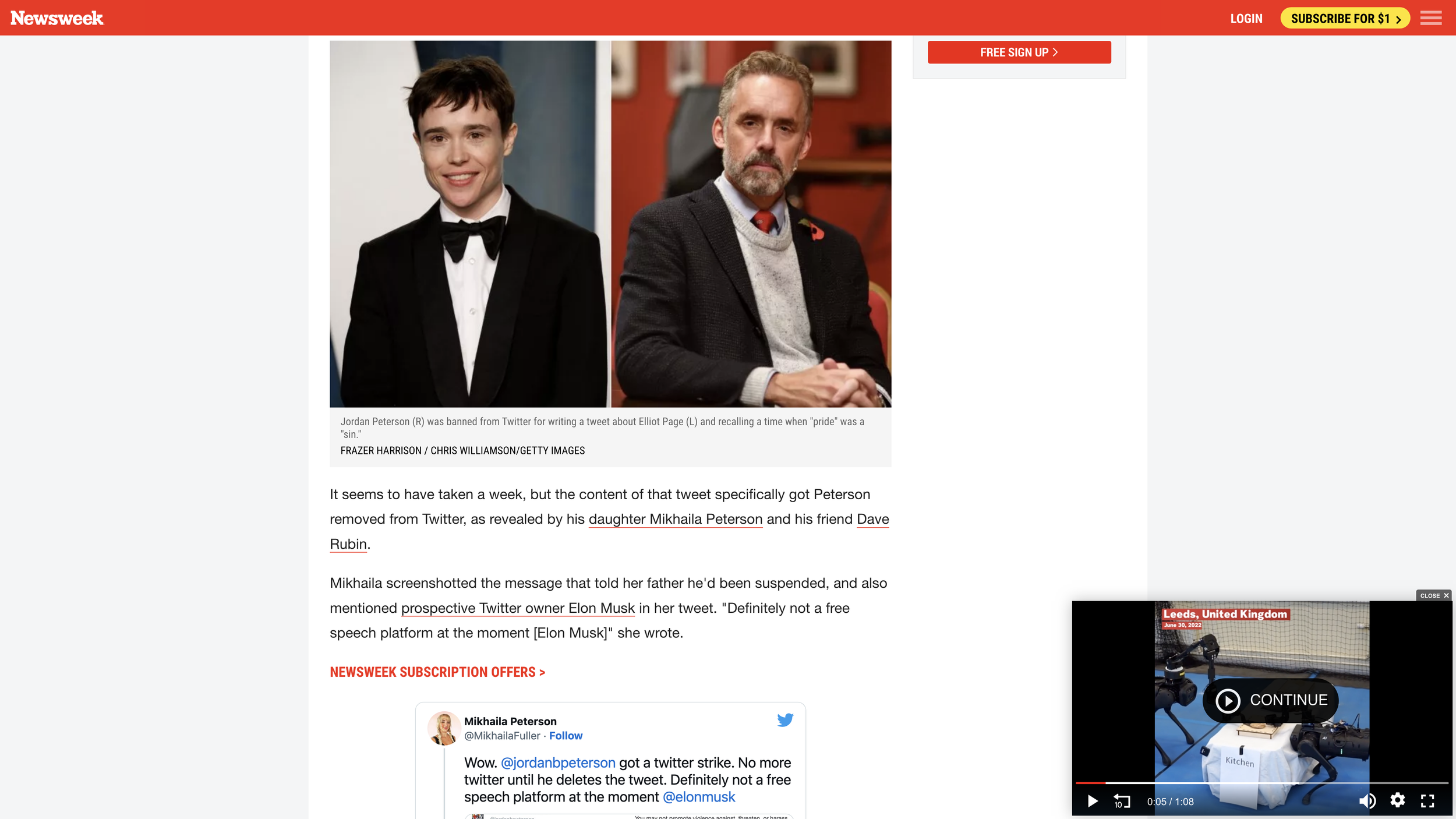

Remember when pride was a sin? And Ellen Page just had her breasts removed by a criminal physician.

Jordan’s Twitter account is frozen unless he deletes the Tweet using a button that says “By clicking delete, you acknowledge that your Tweet violated the Twitter rules.” In a YouTube response, he said he “would rather die” than delete the tweet by his own action and doubled down with a critique of what is typically called “gender-affirming surgery,” performed on teenagers. His complaint with Elliot Page (formerly Ellen Page) is primarily that, as a role model (being a famous actor), Elliot might inspire more teenagers (mostly young women who would like to transition to being men) to deal with gender dysphoria by getting radical, dangerous, irreversible surgery. In his YouTube response to the Twitter ban, Jordan grudgingly allows that perhaps Elliot should have the right to undergo surgery to feel more like a man, but criticizes Elliot for encouraging others to do so.

My own experience with anyone who is transgender is limited to very positive experiences with Deirdre McCloskey. I don’t myself know what the right policies are in this area, though I tend to have Libertarian instincts, without being a full-fledged Libertarian. What I want to argue for, though, is that it is not only permissible, but essential, that our society have a vigorous debate about the appropriate age of consent for gender-affirming surgery. Parental input is another complicated issue, but I doubt anyone would say that a 6-year-old asking for gender-affirming surgery should be absolutely determinative, and let me write as if we agree that at age 30, anyone should be allowed to make that decision. Where should the line be drawn between 6 and 30? We default to age 18 on many things when faced with arbitrary determination of an age of consent. In this case, 18 is enough after puberty that it may cause technological problems to wait that long. But surely that makes figuring out good rules a societal decision that should be considered difficult rather than thinking it means we should short-circuit discussion by insisting peremptorily that technological concerns should trump concerns about the ability of teenagers to make wise irreversible decisions.

Let me make two analogies that suggest we should allow discussion about the age of consent for gender-confirming surgery—two analogies to suggest a range of views about this issue.

First, many feel plastic surgery for people who begin with a low normal appearance can be very helpful for their self-esteem and can really change their life for the better. Others fear that too many people are driven to get plastic surgery because of social pressure—or at least that this is true in some places, such as South Korea. Surely, people should be allowed to take either side in this debate!

Second, many (including me) feel that taking Psilocybin (the key ingredient in psychoactive mushrooms) can be very helpful to people in orienting their lives and may save the lives of a substantial fraction of those subject to suicidal ideation. Proponents of this view would like to see more states legalize the careful administration of Psilocybin, as Oregon has done. Others, for reasons I don’t fully understand, feel that clinical use of Psilocybin should not be allowed. Surely, however wrongheaded they are, we should not someone for arguing that Psilocybin should remain illegal.

If people should not be shouted down for expressing the view that the age of consent for gender-affirming surgery should be higher than it is, then the justification for requiring Jordan Peterson to delete his tweet in order to get his Twitter account unlocked becomes very thin.

Let me parse some of Jordan’s specific words.

“Sin”: Jordan loves the etymology of the word for sin in Greek. “Hamartia” means literally to miss the mark. So the claim here is that “Pride misses the mark.” Also, there is a well known Biblical verse: “Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall.” A reasonable interpretation of this part of Jordan’s tweet is therefore: “The current left-wing position and approach in the culture wars misses the mark and evidences a haughtiness that could lead to worrisome consequences for our society.”

“Ellen”: To some extent, Jordan’s use of “Ellen Page” to refer to Elliot Page is simply a reaffirmation that “The current left-wing position and approach in the culture wars—including especially its insistence on controlling other people’s speech—misses the mark and evidences a haughtiness that could lead to worrisome consequences for our society.”

Deadnaming, as in Jordan’s use of “Ellen” to refer to Elliot, is essentially a refusal to accept someone’s requests for how they should be referred to, plus perhaps a skepticism of that transgender transitions fully change someone’s gender. Skepticism that transgender transitions fully changes someone’s gender is a view that is likely shared by half of the American population. I don’t think that view should be beyond the pale. It is not denying anyone’s full humanity.

Stepping away from the transgender aspects of the situation, calling someone by a name they don’t like is extremely common in heated debates. For example, when Merrill Bateman was the President of Brigham Young University, punishing professors for espousing moderately liberal views, someone I knew referred to him in conversation as “Master Bateman.” (I was denied a job at BYU during this period—when I was a believing, temple-recommend-holding Associate Professor at the University of Michigan—for being too liberal.) Should (and does) Twitter reliably lock someone’s account for name calling? Or is it the transgression of the transgender orthodoxy that Twitter is responding to? Moreover, I think it would be a serious misreading of Jordan’s intent to think that he was trying to insult Elliot. His intent was to dispute the transgender orthodoxy. For Jordan, it wasn’t really about Elliot, except as an example of a broader issue.

“Her”: The things to say about Jordan’s use of the word “her” are almost identical to the issues with his use of “Ellen.”

“Criminal physician”: In his YouTube response, Jordan makes clear that he does, indeed, think that many of the gender-affirming surgeries that are performed should be outlawed. Just as important, and just as clear in his response, is that he thinks the social esteem in which surgeons who do such operations are held should be low. He is not advocating non-state violence or forcible action against such physicians, only laws restricting gender-affirming surgeries and social pressure against the number of gender-affirming surgeries being performed under the status quo.

Overall, there is no question that Jordan is emphatic in the expression of his views. But the views themselves and his expression of them seem well within the bounds of reasonable debate to me.

Let me say that, in his YouTube response, I think Jordan is too harsh about Elliot’s own decision, if it is possible to separate Elliot’s own decision from the charismatic example that it sets that might inspire and encourage many unhappy teenagers to make a female to male transition. In his 2017 Maps of Meaning lectures, Jordan emphasizes the ultimate responsibility of the individual to make decisions for their life, saying “What if no one knows any better than you?”:

In Jordan Peterson’s case, there are two reasons for me to defend him. First, freedom of speech is very dear to my heart. I left the Mormon Church because it was against freedom of speech within its orbit (church law, with excommunication and claimed suffering in the afterlife as the greatest penalty, not civil law). I am not about to cotton to abridgement of freedom of speech by a secular orthodoxy. (As an aside, there is an eerie similarity between the issue of deadnaming and the Mormon Church’s current insistent that it not be called “the Mormon Church,” but only by its full name of “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.)

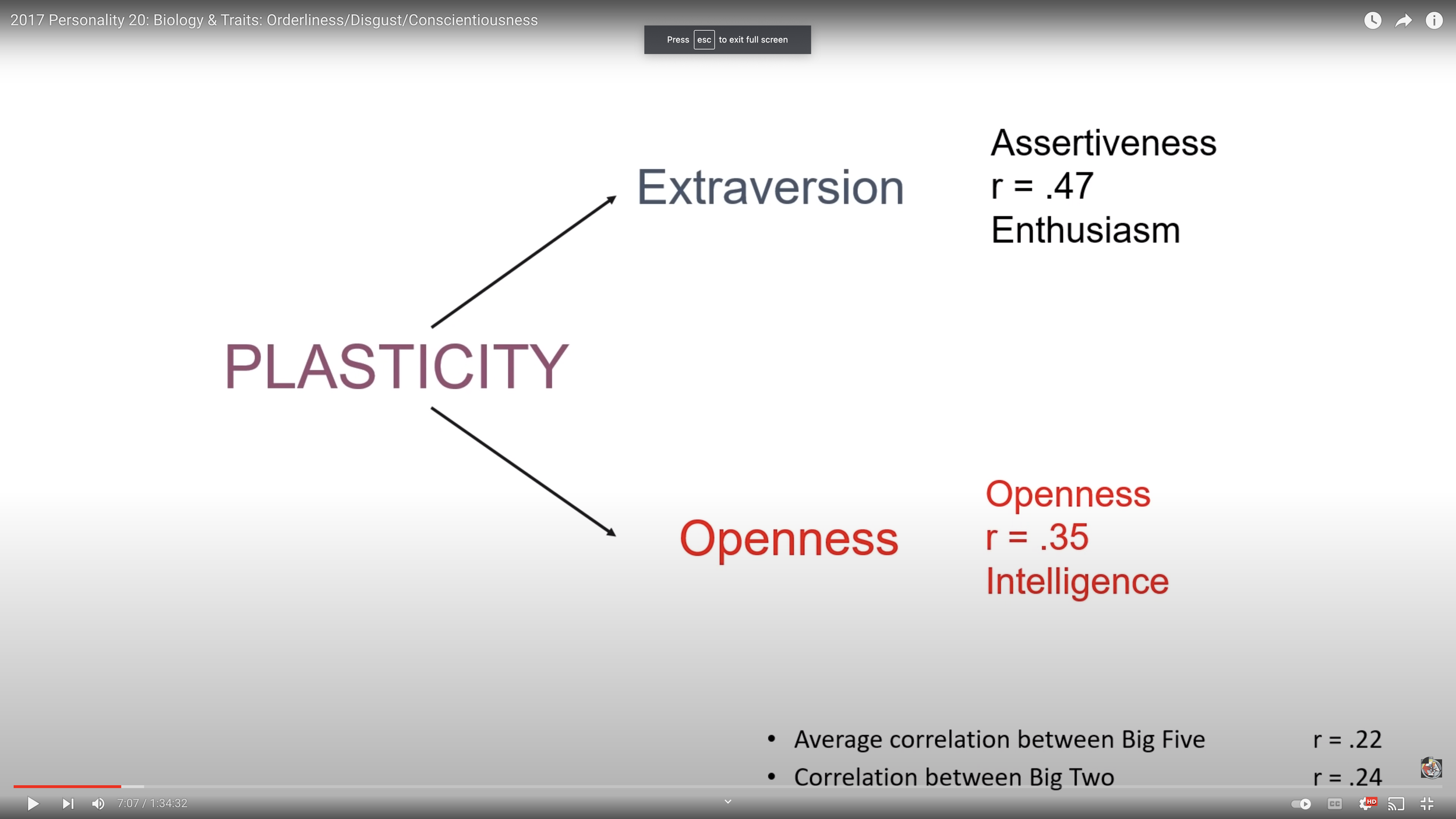

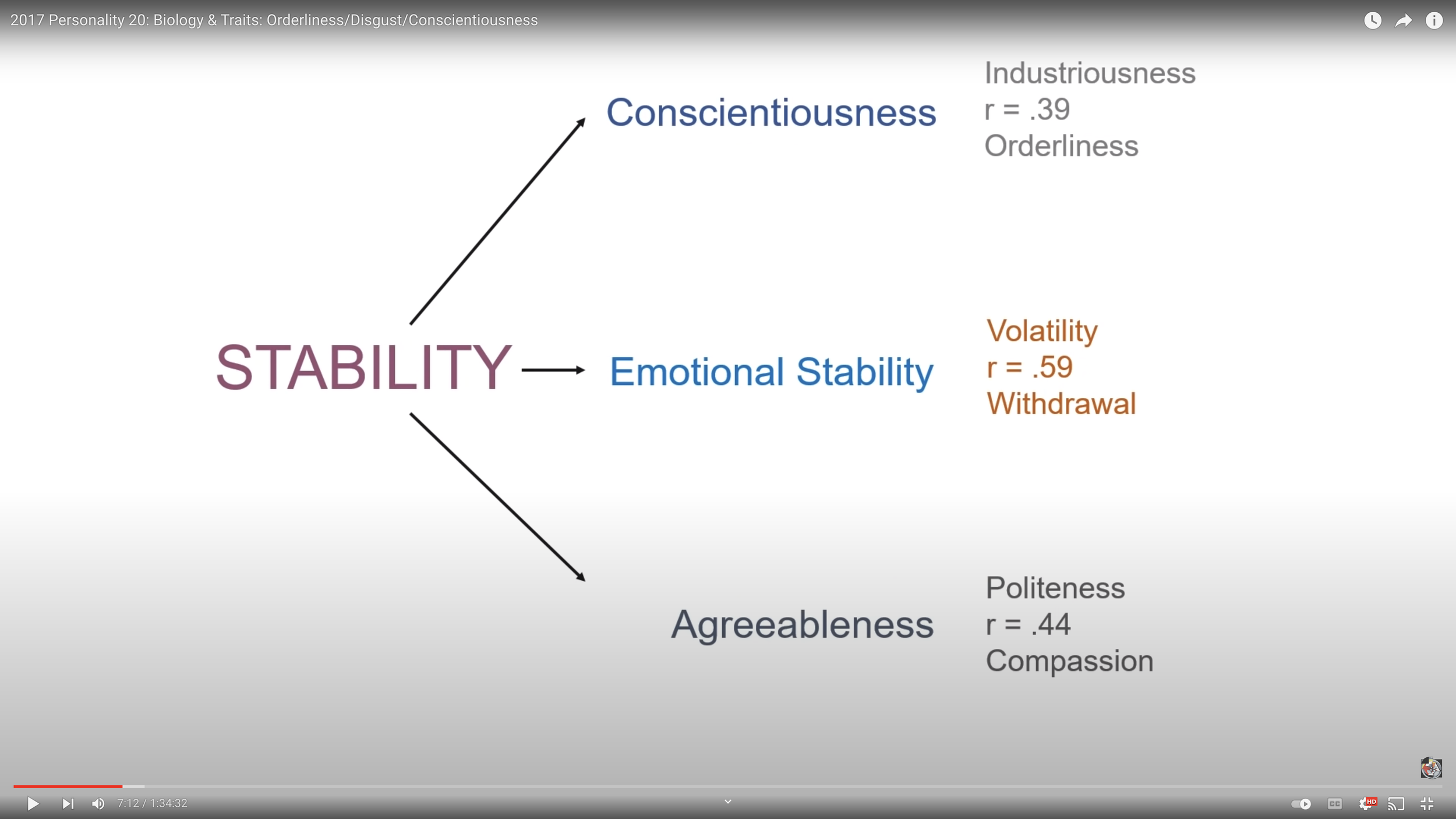

Second, Jordan Peterson is a brilliant exponent of important ideas. (I do not consider his views on transgender issues to be in that category. On the political Right, they are fairly conventional, unoriginal views.) Jordan being “controversial” in an area as charged as transgender issues could easily be enough to make many of my fellow academics stay away from reading or listening to Jordan Peterson entirely. That would be a mistake. In many areas—especially in the lectures and other long-form monologues in his YouTube videos—he is a deep and astute social commentator. (The short form of Twitter does not suit him well.) In his books 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos and Beyond Order: 12 More Rules for Life, he gives advice that makes many people’s lives dramatically better. And in my view, he has gone further than anyone else in showing, in a practical sense, how to put the message of Christianity (and to some extent Judaism) on a nonsupernaturalist footing. That is an enormous achievement, in an area that I have taken as part of my own lifework. (To get a sense of my efforts in this area, see for example “How the Historical Jesus Set the Oppressed Free” and the sermons I have posted, including “Godless Religion,” “The Message of Jesus for Non-Supernaturalists” and “The Message of Mormonism for Atheists Who Want to Stay Atheists.”) Don’t disregard all of Jordan Peterson’s ideas because you are shocked or concerned by some! People who make other people think hard usually have at least one idea that is at serious variance with elite conventional wisdom. And in 2022, many feel protective of elite conventional wisdom at the “circle-the-wagons” level. Don’t let those forcefully protective of elite conventional wisdom scare you away.