Why We Want More Jobs

PODCAST BASED ON THIS POST CREATED BY GOOGLE’S NOTEBOOK LM

All I know of the book above is the cover. But it raises a good question: "Why do we want more jobs?" Inside the models taught in Principles of Economics, people don't want more jobs. In those models, if anyone worked any more, they would be working more than they wanted to. In those models, the firms and the government also think everyone is working just the right amount, too. Famously, some of those who believe too much in models along the lines of this taught in Principles of Economics argued that the Great Depression was caused by people suddenly deciding they hated working more than they used to—a story that seems at some variance with the narrative history of the Great Depression. So what is difference between the real world and those models that makes households, the government and firms all cheer when employment goes up?

Before tackling the question, I need to clarify the question I have in mind. First, I think it is obvious why people who earn wages want high wages. That is not my question. My question is why we like the idea of more jobs even at the current wages. And firms that employ people dislike having to pay high wages, while most firms seem to like the idea of aggregate employment going up.

Second, when I say we want more jobs, I am ignoring the effect of more jobs on inflation. The Fed could probably drive the unemployment rate down to 1% for a while, but if it tried to keep it there, for ten years, without any other policy change other than monetary policy, it is almost certain that inflation would go up, up and away into hyperinflation. So when I ask why we want more jobs, it is equivalent to asking why we wish that more jobs weren't so inflationary. If we didn't want more jobs, we wouldn't care if more jobs were inflationary, since on other accounts we didn't want more jobs anyway. But we do want more jobs, it is sad that having a lot of jobs would ultimately be quite inflationary.

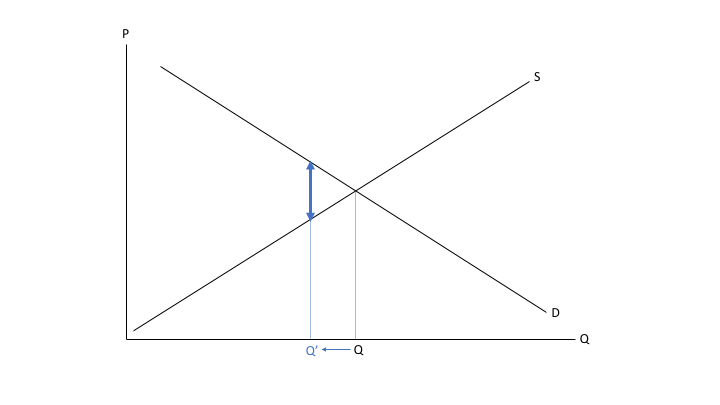

My answer boils down to three wedges. I might have titled this post "The Three Wedges," but then many potential readers would have no clue what it was about. Economists use the word "wedge" to describe a situation where some transactions that would make both parties better off don't happen because the buyer is being charged more than what something is worth to the seller. The simplest case is a tax wedge. Take a simple sales tax like the gasoline tax. If the seller is charged the tax, you could think of it is a shift in the supply curve, like this:

If the buyer is charged the sales tax, you could think of it as a shift in the demand curve, like this:

But for same size tax, the effect is the same: the reduction in the quantity sold is the same, the amount the buyer ends up paying is the same, and the amount the seller ends up getting is the same. So regardless of who is paying the tax, economists like to think of the tax as a gap or "wedge" between the price the seller gets and the amount the buyer pays, like this:

Once you get use to it, this is a much easier way to think about the effects of taxes than shifting the supply curve or demand curve. The two-sided blue arrow is the tax wedge. And the triangle formed by the two points of of that two-sided blue arrow and the intersection where things would be if there were no tax is the deadweight loss triangle. The deadweight loss triangle represents the value of the good transactions that don't happen because of the tax.

If there are three wedges instead of one, then the situation looks like this:

With three wedges, the quantity bought and sold goes down a lot more, and the deadweight loss triangle is much, much bigger. Typical formal macroeconomic models in the economics journals only deal with one of the wedges listed below at a time, and so miss how much bigger the issues are when one wedge piles on top of another.

Here are the three wedges:

The Product Market Wedge: P > MC

To me, increasing returns to scale are central to macroeconomics. Three of my blog posts focus on this:

Why I am a Macroeconomist: Increasing Returns and Unemployment

Returns to Scale and Imperfect Competition in Market Equilibrium

If it were just as efficient and productive to have one person working alone as to have big firms, everyone could be self-employed, and there would be no problem of unemployment. So increasing returns to scale is central to unemployment. Direct evidence of increasing returns to scale comes from the business world, where business people talk about having a fixed cost that can be spread over more units if they can increase the scale of their operations. I consider the kind of increasing returns to scale one gets from having a fixed cost and constant marginal cost quite reasonable. This yields an average cost curve that declines from a high value and ultimately gets very close to the flat average cost curve.

This, not the ridiculous U-shaped average cost curve, is what should be taught to students in their microeconomics classes. (See my Wakelet story "Is There Any Excuse for U-Shaped Average Cost Curves?")

As discussed in detail in "Returns to Scale and Imperfect Competition in Market Equilibrium" (and in "Next Generation Monetary Policy"), as long as there is free entry and exit of firms, increasing returns to scale goes hand in hand with imperfect competition. There is also direct evidence of imperfect competition. If a firm can raise the price of a product without losing every last customer, it faces imperfect competition. If a firm has to work hard to sell more at the same price, it faces imperfect competition. If a firm even is in the position of setting its own price at all, as opposed to just accepting a price determined on some exchange, then it faces imperfect competition.

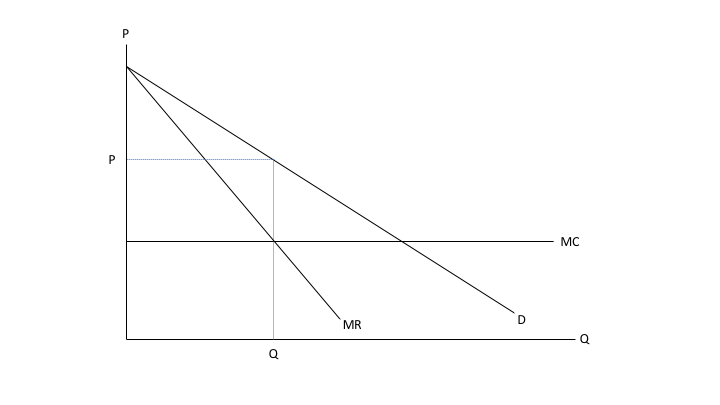

Under imperfect competition, when a firm adjusts its price, it should look for a price that, on average, is above its marginal cost. The graph for either a monopolist or a monopolistic competitor looks like this:

The marginal revenue curve shows how much the firm makes by selling an extra unit if it has to cut its prices overall in order to sell an extra unit.

Now think of the firm's situation in the short run when it doesn't adjust its price. To be concrete, suppose it costs a firm $1.60 to produce a widget, but the firm sells a widget for $2. In that situation, a firm makes extra profit of 40 cents on every extra widget it sells if it didn't have to make any effort to sell that widget. As mentioned above, if it had to cut its prices to sell an extra widget, that doesn't get the firm ahead. And if it has to pay for advertising to sell an extra widget, that might not be so attractive. But if the economy as a whole heats up so that the firm sells an extra widget without any extra effort, that is going to look great to the firm:

This is an example of the firm being able to sell more widgets without extra effort, and make 40 cents on each extra widget it sells. So on this account, the firm is happy about the economy heating up. If wages get pushed up, that is good for the workers and bad for the firm. But leaving that aside, the firm cheers any increase in aggregate demand because of the extra profit that goes along with higher sales.

The Firm's Willingness to Pay for Labor: To translate from the price and marginal cost of widgets to the value of what a worker produces and what the firm is willing to pay, imagine that an extra hour of work leads to 10 extra widgets being produced. Then at $2 per widget, the value of the extra production from an extra hour of work is $20: the price times the 10 widgets per hour marginal physical product of labor. But since selling the extra widgets would require cutting the price of widgets or advertising, the firm only nets $1.60 in marginal revenue after cutting prices to sell an extra widget, so it is only willing to pay $16 an hour: the marginal revenue of $1.60 a widget times the 10 widgets per hour marginal physical product of labor.

(Actually, although this is usually called the marginal revenue product, when marginal revenue is equal to marginal cost, one can also call this the "marginal cost product." And in the short-run when prices are sticky it is the marginal cost product (the marginal cost times the marginal physical product of labor), not the marginal revenue product (marginal revenue times the marginal physical product of labor) that matters. Indeed, while a price is sticky, marginal revenue doesn't do anything at all. Marginal revenue only matters when a firm is in the process of adjusting its price. So it would be odd if marginal revenue product mattered while a firm has a temporarily fixed price. It doesn't. While a firm has a temporarily fixed price, it is the marginal cost product that tells how much a firm is willing to pay a worker.)

The Marginal Tax Rate Wedge

Since I started explaining the idea of wedges by talking about tax wedges, it shouldn't be hard to understand the marginal tax rate wedge. I have in mind taxes like social security taxes where the total amount of tax goes up with one's total labor income or income taxes that go up with one's total income, including labor income. It is very important here to distinguish between a lump-sum tax that may be painful, but doesn't get any worse if one works more, and something like social security wage taxes or a general income tax that goes up if one works more. (See “How Marginal Tax Rates Work” and the links it has at the bottom of the post.)

Suppose that, combining both the firm's and worker's social security taxes and income taxes, the marginal tax rate for an extra hour of work is 25%. Then the firm is willing to pay $16 an hour, but after all those taxes, if the firm shells out $16 an hour, the worker gets 25% less: only $12 an hour. $4 an hour goes to the government through the IRS.

This is now the second reason we want more jobs. When there are more jobs, there is more government revenue. That means the government can pay off the debt, provide more public goods or transfers, or cut taxes: all good things. People may disagree about what to do with the extra government revenue, but something desirable is likely to happen. So when aggregate demand goes up, the government and the taxpayers and those who benefit from government purchases and transfers cheer.

The Labor Market Wedge

The most difficult of all the wedges to suss out is the labor market wedge. We don't fully understand it, but we know it is there. How? Even at the after-tax wages on offer after the firm worries about the difficulty of selling more goods and the government takes its cut, workers are happy to get jobs.

In the example I have been laying out, suppose that someone is happy to get the $16 an hour job that nets $12 an hour after taxes. If they are happy to get the job, rather than just feeling meh about it, what they are giving up—namely, the cool things they could be doing at home or out and about—must be worth less than $12 an hour to them. To be concrete, let's say the opportunity cost of their time is $8. Then, the social marginal benefit of an hour of their work is $20, while the social marginal cost of an hour of their work is only $8. If they work an extra hour due to extra aggregate demand, society as a whole is $12 ahead:

the firm is $4 an hour ahead due to extra profits

the government and taxpayers are $4 an hour ahead due to extra government revenue

the worker is $4 an hour ahead due to the $12 an hour after-tax wage being higher than the $8 an hour opportunity cost of time

These are all good reasons for us to want more jobs.

Why would a firm stop hiring with an after-tax wage of $12 an hour instead of hiring more workers at a lower wage when workers might be willing to work for $8 an hour? One possibility is wages kept up by a minimum wage or a wage a union insists on. Another possibility is that a wage higher than the opportunity cost of time is necessary to induce workers to go through the arduous process of searching for a job. But my favorite explanation is efficiency wages: higher wages make a job valuable, so the worker has something to lose if they get fired. So higher wages give workers an incentive to do what the boss tells them to. I discuss this in detail in "Janet Yellen is Hardly a Dove—She Knows the US Economy Needs Some Unemployment."

The Bottom Line

Higher aggregate demand that raises sales and employment makes profits, government revenue, and household utility go up. So what's not to like? Inflation. Unfortunately, the three wedges mean that extra output and the jobs the extra output brings become inflationary long before we are at the level of jobs we would otherwise like to have. Firms pushing price above marginal cost makes output inflationary sooner. Taxes that go up with income make output inflationary sooner. And anything that pushes wages above the bare minimum people needed to get people to work makes output inflationary sooner.

Inflation—and not just a little inflation, but the specter of hyperinflation—is the threat that enforces supply-side relationships. By supply-side relationships, I mean simply the real equations that determine the medium-run equilibrium and the long-run equilibrium of the economy. On these ideas, see "The Deep Magic of Money and the Deeper Magic of the Supply Side" and "The Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate and the Short-Run Natural Interest Rate."

There are many things that can be done to get output and employment closer to the ideal level and get the extra jobs we want:

antitrust to reduce the degree of imperfect competition and get prices down closer to marginal cost

lower marginal tax rates to make what workers get after taxes closer to what firms pay

ways of putting the fear of the boss into workers or getting workers to work hard on the job that don't depend on losing a job being a terrible thing for the worker

There are also policies to raise productivity for a given number of work hours and so have a bigger pie. Prominent among these is government funding of basic research, which could easily be worth the extra distortion from somewhat higher taxes if it was funded by the income tax.

But none of these are monetary policy. Close to the best that monetary policy can do is to keep output at the "natural" level of jobs that is neither inflationary nor disinflationary. The natural level of jobs is below the ideal level of jobs in the absence of inflationary worries. But it is sustainable, where the otherwise ideal level of jobs is not. And it is likely to be better than the other sustainable policy of sometimes having more jobs than the natural level and sometimes having fewer. That policy is likely to have such a big deadweight loss triangle when jobs are fewer, that it isn't worth it, even though it is nice to sometimes have more jobs. You can see more on this in this Powerpoint file.

Conclusion

Many macroeconomics courses fail to ever explain our intuition that it would be good to have more jobs. The feeling that it would be good to have more jobs is so basic to the real world, a macroeconomics course that fails in this respect fails in an important way. I hope this post helps fill the gap.

Postscript, added March 20, 2020

The three wedges above all make us want more jobs. Is there anything that could make us want fewer jobs if it were bigger than all the three wedges above combined? Theoretically yes, if the activities of those jobs would create large negative environmental externalities that are not taken into account by firms and households. Fortunately, if this is the case, there are policy remedies. For examples, see “How to Fight Global Warming.”