There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale

There is no such thing as decreasing returns to scale. Everything people are tempted to call decreasing returns to scale has a more accurate name. The reason there is no such thing as decreasing returns to scale was explained well by Tjalling Koopmans in his 1957 book Three Essays on the State of Economic Science. The argument is the replication argument: if all factors are duplicated, then an identical copy of the production process can be set up and output will be doubled. It might be possible to do better than simply duplicating the original production process, but there is no reason to do worse. In any case, doing worse is better described as stupidity, using an inappropriate organizational structure, or X-inefficiency rather than as decreasing returns to scale.

The replication argument is extremely valuable as a guide to thinking about production since it often identifies a factor of production that might otherwise be ignored, such as land, managerial time, or entrepreneurial oversight. Thinking through what difficulties there might be in practice in duplicating a production process at the same efficiency helps to identify key factors of production if those factors of production were not already obvious.

The nonexistence of decreasing returns to scale implies that the U-shaped average cost curve still taught routinely to most economics students, with its decreasing returns to scale region, is not what it seems. I got into a debate about this on Twitter, which I storified in "Is There Any Excuse for U-Shaped Average Cost Curves?" A U-shaped average cost curve might be justifiable as a cost-curve per top-level manager, or perhaps as a cost-curve per entrepreneur. But including all inputs, including both managerial and entrepreneurial time and effort, production must still be at least constant returns to scale if not increasing returns to scale.

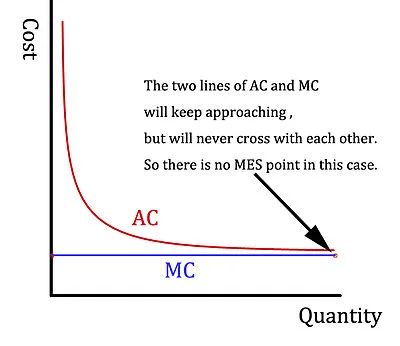

In addition to crowding out the clarity of the replication argument, the emphasis in many economics classes on the so-called U-shaped average cost curve makes it harder for students to get the idea of increasing returns to scale clearly in their minds. Much better would be to use something like the graph below to teach students about increasing returns to scale:

Given the replication argument, there is no scale of operation that is beyond efficient scale. There may be ample reason to make different plants or divisions quasi-independent so they do not interfere with one another's operations. But that is not an argument against scale per se. There may even be reason to set up incentives so that different divisions are almost like separate firms, headed by someone in an entrepreneurlike position. But that still is not, properly speaking, an example of diseconomies of scale.

Even those who disagree with me on some of the points above should agree that a debate on these issues, beginning with the challenges I have made above, would be good for student understanding of production.

Besides pedagogical inertia—enforced to some extent by textbook publishers—I am not quite sure what motivates the devotion in so many economics curricula to U-shaped average cost curves. Let me make one guess: there is a desire to explain why firms are the size they are rather than larger or smaller. To my mind, such an explanation should proceed in one of three ways, appropriate to three different situations.

If returns to scale are constant, then everything can be done on a per manager or per entrepreneur basis. This might still use diagrams similar to U-shaped average cost curves, but would be quite explicit about the fact that one factor was held constant, so that the upward-sloping part of the U-shaped average cost curve does not represent true decreasing returns to scale, but rather decreasing returns to scale in all other factors when managerial or entrepreneurial input is held constant.

If returns to scale are increasing, the size of the firm can be made determinate by having a downward-sloping demand curve. (I discuss in some detail the relationship between increasing returns and imperfect competition in "Next Generation Monetary Policy" and hope to return to discussing this relationship in a future blog post.)

If the firm is large enough relative to its suppliers and labor force that increasing its scale noticeably increases factor prices, that may limit a firm's scale. This is not properly decreasing returns to scale simply because returns to scale is defined over quantities, and so when translated into cost terms is effectively defined for given factor prices. In any case, to my mind, the analytical distinction between the production function and interaction with factor markets is an analytical distinction worth highlighting.

What I am most confident of is that microeconomic teaching of production as we know it, with the U-shaped average cost curve in center stage, is suboptimal. Let's change it. The way I think about production may not be the best way, but the way it is now taught is definitely not the best way.

Don't miss the followup post: "Returns to Scale and Imperfect Competition in Market Equilibrium."

Update: In addition to the comments below (visible when you go to the post itself or click on the post title), this post has sparked a vigorous debate on Twitter, which I organized in this Storify story: "Up for Debate: There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale." In these storified tweets, I answer many questions you may have as well. I will try to keep that story updated. And here is a link to the debate on my Facebook page.

Here are some of the most instructive comments, and some of my replies:

Chris Kimball: The replication argument is so obviously correct that every "diminishing return to scale" presentation is implicitly or explicitly holding one or more factor constant. That much seems near tautological. As a result, this strikes me as a pedagogy discussion. What's the preferred way to tease out these concepts? Given the fact that in the real world there really are constraints both internal and external, factors really are limited, and perfect replication is a thought experiment more than an observation.

Miles: Absolutely. We are thinking along very much the same lines.

mike: But isn't franchising an example of where people realize that to get a local manager that cares at 2,000 locations, its better to seperate ownership interests. You talk about territory distribution etc, but I would argue that is an example of needing that remedy to overcoming decreasing returns to scale.

Miles: I love your example of a franchising system. This is exactly what I mean by having a firm organization that allows one to replication owner/entrepreneurs. The franchisees become one more input in the system from the point of view of headquarters. I wish I had thought of this example!

Patrick Neal Russell Julius: My favored way of explaining this is describing the last factor of production as "planets". If you were to copy the Earth in its entirety, in every detail, it strains all credulity to imagine that you could do any less than double total output. So there must be SOME factor of production that would allow you to have at least constant returns to scale—though if it is indeed planets, obtaining more of that factor might be quite prohibitive even in what we normally call the "long run".

Chris Makler: ... workers being homogenous fails ... If your production function only involves computer servers, fine; double the servers, double the traffic (or even more, but you get the point). But once you start hiring humans it's completely different. By definition if you have 10 slots to fill and 30 applicants, you fill the slots with the 10 people who are the best match. If you have 20 slots to fill, you go down the list. So DRS follows directly from some form of match-specific productivity.

Miles: This is very interesting. After adjusting for input quality, the amount of labor doesn't really double when the firm goes from 10 employees to 20. But "quality" of a worker may be firm specific, and so not visible in other data that isn't specific to the firm.

In the Twitter debate storified in "Up for Debate: There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale," the most interesting discussions to me were about communications within the firm and the production of software. Here is my summary of the issues and what I think is their resolution:

Communication Within a Firm: If every employee is encouraged to talk to every other employee, then the number of communication lines goes up with the square of the number of employees. A vast volume of communication could start to drag down production. The answer I give is that as an organization grows it needs siloing: groups with a lot of communication within the group, but limited communication between groups. Siloing is usually only mentioned in order to criticize it, but siloing has the huge benefit of helping to keep people from being overwhelmed with emails, for example. The trick is to get interaction between groups where that interaction is likely to be helpful, and avoid interaction between groups where that communication is a cost with little benefit.

The Writing of Software and Books, Recording of Songs and Shows, etc.: Sam Vega asks "Doesn't throwing more programmers at a software project qualify as "decreasing returns of scale"?" There are two perspectives one can take here: thinking about copies of the software, book, song, shows, etc. (whether physical or digital copies) and thinking about different software programs, texts, songs, shows etc.

From the perspective of copies of the software, book, song, show, etc., the writing and recording is a fixed cost. Throwing more programmers at writing the software to try to do things faster raises the fixed costs and increases the returns to scale for the copies.

From the perspective of distinct software programs, books, songs, shows etc., the key point is that the replication argument only applies to the production of identical items. Leaving aside copies, you only need one of the code for each type of software. If you are only going to produce one, then returns to scale don't apply. On the other hand, if you are willing to consider an array of different computer games, say, as distinct but on par (a symmetry assumption), then it should be possible to create 10 distinct games in the same amount of time if one has ten times the input.

Another way to put it is that cutting the time it takes to produce something in half is not at all the same as producing twice as much of something in the same amount of time.

Don’t miss the follow-up post “Returns to Scale and Imperfect Competition in Market Equilibrium.”