Niklas Blanchard writes this about “Debt Overhangs, Past and Present” in his post in this debate with Krugman (see this full account of my discussion with Niklas):

There is a lot not to like about the Reinhart, Reinhart, and Rogoff study, and Krugman nails much of it; it doesn’t deal with causation. I’m actually kind of confused as to why Miles mentions the study (although he may enlighten me in the comments). However; more importantly, it doesn’t specify 90% debt: GDP as a regime change to a new steady state, or as a transitory experience resulting from something like a recession, or a war. In normal times, the regime change itself is the cause of the turbulence, not the subsequent destination (like going over a waterfall). There is ample evidence that suggests that countries with high transitory debt loads are able to deal with them without incident — provided they return to robust nominal growth. Japan deals with it’s sky-high debt load through financial repression and ultra-tight monetary policy. The cost of this type of action is that the government steals wealth from households.

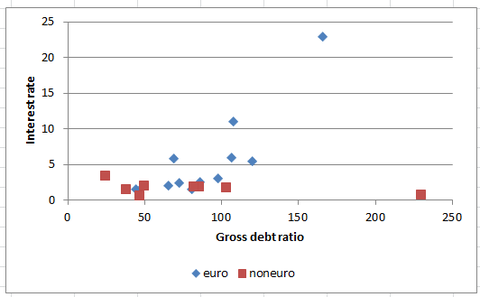

In retrospect, I should have avoided the word “threshold,” with its suggestion of a sudden change. I never intended to suggest there was a sudden regime shift. Of course, the 90% debt/GDP ratio is a somewhat arbitrary level that Carmen, Vincent and Ken use to cut their data. But, looking at the whole set of 26 historical episodes above that debt/GDP ratio, there seems ample grounds to be worried about the effects additional national debt might have on Italy’s situation–and I don’t think it is amiss to be worried about the effects additional national debt might have on the situation in the UK or the US. There is no evidence from a randomized controlled trial available for the effects of national debt. So I don’t know how to judge whether we should be worried about the effects of national debt for countries in various situations other than from theory–which I will leave for other posts and columns–or by trying to glean what insights we can from case studies (which is what attempts to find natural experiments would be in terms of sample size), from exercises like the one Carmen, Vincent and Ken conducted in “Debt Overhangs, Past and Present,” or from correlations such as those shown in Paul’s graph above, which suggests that we should be more worried about high debt/GDP ratios for countries that cannot borrow in their own national currency.

Unlike Paul, Noah grapples with my National Lines of Credit proposal–or “Federal Lines of Credit” for the US. (You can see my posts on Federal Lines of Credit collected in my Short-Run Fiscal Policy sub-blog: http://blog.supplysideliberal.com/tagged/shortrunfiscal.) Noah writes:

However, I do have some skepticism about FLOCs. First of all, there is the idea that much of the “deleveraging” we see in “balance sheet recessions” may be due to behavioral effects, not to rational responses to a debt-deflation situation. People may just switch between “borrow mode” and “save mode”. In that case, offering them the chance to take on extra debt is not going to do much. Second, and more importantly, I worry that FLOCs might draw money away from infrastructure spending and other government investment, which I think is an even more potent method of stimulus; govt. investment, like FLOC money, is guaranteed to be spent at least once, but unlike FLOCs it can increase public good provision, which is a supply-side benefit.

In answer to Noah’s first bit of skepticism, the main point of National Lines of Credit is to encourage more spending by that fraction of the population that will spend as a result of being able to borrow more, without adding to the national debt by sending checks to people like those in “save mode” who won’t spend any more. If people don’t draw on their lines of credit from the government, it doesn’t add to the national debt. And even if people draw on their lines of credit from the government to pay off more onerous debt, this is likely to both (a) make them better credit risks–that is, more likely to have the means to pay the government back and so not add to the national debt and (b) make them feel more secure, and so possibly get them to switch at least a little bit from “save mode” to “spend mode.”

On infrastructure spending, I should say more clearly than I have in the past that spending more on fixing roads and bridges would likely be an excellent idea for the US on its own terms, because of the supply-side benefits. But if it crowded out a Federal Lines of Credit program, one has to consider that Federal Lines of Credit can get more than a dollar’s worth of first-round addition to aggregate demand (which is then multiplied by whatever Keynesian multiplier is out there) per dollar budgeted for loan losses, while spending on infrastructure gives exactly one dollar worth of first-round addition to aggregate demand (which is then multiplied by whatever Keynesian multiplier is out there) per dollar budgeted for that spending. The spending on roads and bridges has to have enough of a positive effect on later productivity and tax revenue to outweigh its less potent stimulus per dollar budgeted. The other big problem with additional infrastructure spending is that, alas, it cannot be turned on and off quickly. The legal, administrative and regulatory process for spending on roads and bridges is just too slow to be of much help in short recessions, or if one wants to hasten a recovery that has already built up a good head of steam. So our current situation is one of the few in which spending on roads and bridges would be a fast enough mode of stimulus. Most of the time, roads and bridges should be seen primarily as a valuable supply-side measure when infrastructure is in the state of disrepair seen in the US.

I said that Noah, unlike Paul, grapples with my National Lines of Credit proposal. Indeed, Paul shows no evidence of having read the second half of my article. One theory is that he really didn’t read the second half. Most favorably, Paul could be saving discussion of Federal Lines of Credit (and electronic money, which I also discuss in “What Paul Krugman got wrong about Italy’s economy”) for other posts. The most intriguing theory (that is not as positive as the idea that Krugman posts on FLOC’s and electronic money are coming, and one that I would not give all that high a probability to) is that Paul likes my proposals enough that he wanted to point people to those proposals, and too much to criticize them, but thinks they are too controversial to implicitly endorse by discussing them without criticizing them. If so, I am grateful to Paul for that backhanded support. Noah has a theory (that does does not preclude this theory that Paul is intentionally flagging my proposals while keeping some distance):

That said, I think the FLOC idea is an interesting one. Why have most stimulus advocates ignored it? My guess is that this is about politics. In an ideal world, pure technocrats (like Miles) would advise politicians in an honest, forthright fashion as to what was best for the country, and the politicians would take the technocrats’ advice. In the real world, it rarely works that way. For every technocrat who just wants to increase efficiency, there’s a hundred hacks and politicos who are only thinking about distributional issues - grabbing a bigger slice of the pie. These hacks are very willing to use oversimplified narratives and dubious sound bytes to embed their ideas in the public mind. And that kind of thing really seems to be effective.

This means that politics’ response to policy is highly nonlinear - give the enemy an inch, and they take a mile. It also means the response is highly path-dependent; precedent matters.

So Krugman et al. may be ignoring FLOCs and other stimulus engineering tricks because of political concerns. If they concede for a moment that debt is scary, it will just shift the Overton Window toward Republican types who are deeply opposed to any sort of stimulus, and would oppose Miles’ FLOCs just as lustily as they opposed the ARRA.

In other words, finding optimal, first-best technocratic solutions might be far less important than simply embedding “AUSTERITY = BAD!!!” in the public consciousness.

My own politics are more centrist (to the extent they fit within the US political debate at all. (See my post “What is a Partisan Nonpartisan Blog?” as well as the mini-bio at my sidebar and Noah’s early review of my blog, “Miles Kimball, the Supply-Side Liberal.”) From that point of view, I have argued in “Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football” (my response to the Mike Konczal post criticizing Federal Lines of Credit that Noah mentions) that Federal Lines of Credit have substantial political virtues in providing a way out of the current political deadlock between the Republican and Democratic parties over economic policy.

Many thanks to Noah for clarifying this debate with Paul, as well as to Niklas Blanchard, whose two bits I discussed in my post a few days ago, and to Paul himself for engaging with me in debate, at least at one level.

Update: With Noah’s permission, let me share an email exchange about the post above:

Miles: Did you like my response?

Noah: I did! It was quite thorough.

I think the criticisms of FLOCs are still basically three:

Criticism 1 (mine): There is a limited amount of political will for increased spending. And because of the supply-side benefits of infrastructure, that finite will is better spent on infrastructure even than on the most cost-effective pure stimulus.

Criticism 2 (Mike Konczal’s): FLOCs have different distributionary consequences than other stimulus approaches, since FLOC borrowers will be responsible for repaying the stimulus borrowing, not taxpayers.

Criticism 3 (Mike Konczal’s): It will be very difficult to handle the inevitable FLOC defaults. Whether they are forgiven or collected aggressively, it will make some people very angry.

Criticism 4 (everyone else’s): FLOCs may get good “bang for the buck”, but they won’t get much bang in total, because people are in “deleveraging” (or “balance sheet rebuilding”) mode.

I think that these are not inconsiderable obstacles to the FLOC idea…

Miles: I don’t understand 4. Here is what I think it means. FLOC’s can be scaled up to get more impact, but they will have decreasing returns since people have consumption that is concave in amount of credit provision. Even though the costs are also concave in the headline amount of credit provision, this means that a FLOC program can only be so big. So ideally we want other things as well–infrastructure and electronic money. Sounds good.

On 1, I would be glad if the debate were between FLOC’s and infrastructure spending.

On 2 and 3, Mike only gets one of these at a time at full force: making the amount of credit provision proportional to last-years adjusted gross income dramatically reduces the repayment problem (and the size of the program can be adjusted to compensate for the lower MPC), but this makes it distributionally less favorable.

Noah: No, I think you may be misunderstanding 3. No matter how much FLOC lending is done, x% of people will default on their FLOC loans. What the government then does to that x% - cancels their debt, sues them, or refers them to collections agencies - is going to be a political bone of contention. It’s an image problem (evil govt. suckering people into borrowing money they can’t afford to pay back), not an efficiency problem.

Miles: I agree. That is why FLOC’s need to be paired with National Rainy Day Accounts that most likely make it unnecessary to ever use FLOC’s again after the first time.

I added the link about National Rainy Day Accounts just now. As a conceptually similar idea to FLOC’s and National Rainy Day Accounts for individuals, see what I have to say about helping the states spend more now (to stimulate the economy) and less later in “Leading States in the Fiscal Two Step.”