JOSEPH: Sarah was number 7 in our family’s children, and I was number 6. There are 22 months between our birthdays. While most of the year she was “two years” younger, she always enjoyed the two months when she was just “one year” younger.

Sarah and I interacted a lot. The year I turned eight our family moved to Provo, Utah, to a house on Oak Lane. Sarah and I had rooms next to each other in the downstairs.

Sarah often wanted to join me and my friends when they came to play, and was disappointed when I said no. I shut her out in other ways, too—often literally. I remember going into my room and putting my foot against the bottom of my door so she couldn’t get in. (The lock didn’t work.) She would bang on the door and yell at me whatever she had wanted to say.

Though a boundary change sent us to different junior high schools, we spent two years together at Provo High. By that time, we had become friends.

One time in our teenage years Sarah called me out when I didn’t know the answer to a question and made something up. She said if I didn’t know something, I should admit I didn’t know. I took that to heart. It made a big impact on my life.

While I was on my mission, Sarah managed apartments a block away from the U of U, and when she went on her mission, I took over the managing from her. The tenants enjoyed her management. She also learned a lot about maintenance from our brother-in-law Teryl, who had managed the apartments before her. She took that hands-on maintenance mindset with her as she remodeled a house on 300 South in Provo and did most of the work herself where she could, and helped the people doing the work when she couldn’t do it by herself.

Sarah loved being involved in the lives of her nieces and nephews as they grew up. I was sad that we never lived close enough for her to interact with my children much beyond family gatherings, but she was a highly-involved aunt bringing her particular brand of good cheer to the lives of Paula’s and Mary’s children.

JORDAN: My sister Sarah would ask so, so, so many questions. When I was younger Sarah's questioning sometimes annoyed me. Over the decades I’ve recognized that her curiosity was a gift. Sarah had an insatiable thirst for the details of our lives and thoughts and opinions of the world at large. Over time I came to believe that in her own way Sarah just wanted to know people as well as she could, with a special attention to family. I recognize it now as one of the ways I can see her love for others, including me.

The day after the terrible freeway accident a couple of weeks ago, I visited Sarah in the intensive care. Sarah had asked that I assist Kevin in giving her a blessing before major surgery to stabilize her fractured spine. Sarah looked so fragile in the ICU bed. I was grateful she had survived such a violent collision. Her scans showed fractures in her spine, ribs, and ankle. Sarah was lying perfectly flat on her back in the ICU bed, staring at the ceiling unable to move because whenever she did there would be excruciating pain. Her surgery had been delayed so we started visiting, the four of us—Sarah, Mary, Kevin, and I. We started talking about memories of growing up. Our relationship with our parents. When Sarah seemed to slow down Mary and started to talk about Mary’s kids and my kids. I stayed and talked and talked, hoping the conversation would be just what Sarah would find interesting and a comforting distraction. That evening when I arrived home I realized that I’d been at the hospital for 5 hours.

During that visit I told Sarah I looked forward to post pandemic times, when we could gather again as family. Family meant everything to Sarah. The same attention she devoted to me and Rebecca and our three children, she devoted to everyone in our large extended family, especially our parents, Ed and Bee. She was the aunt that remembered birthdays, made piñatas too sturdy to break, celebrated milestones, assisted with home improvements, joined in hikes, made time to listen. I told Sarah two Saturdays ago I thought of her as a Keeper of Memories, that I counted on her to share her insights gained from close attention to people’s lives.

I’m devastated over losing Sarah and that those anticipated conversations with her will never happen in this life. I loved you, Sarah. Thank you for loving me and my family and asking so many questions.

MILES: Since her death last Saturday, I have been thinking about the qualities Sarah and I shared, but in which she surpassed me. Sarah was preternaturally cheerful. She was curious about everything, and willing to try almost anything. She was outgoing and made friends easily. She cared about doing the right thing in realms that matter, but she was a free spirit because she cared remarkably little about what anyone else thought of her in all the areas that don’t matter. Above all, Sarah was always herself and never tried to be anyone else. In a world full of tortured souls plagued by self-doubt, Sarah instead found the straightforward enjoyment each day offered.

Many of us take one role or another as a cog in the great machine of society. Sarah was never a cog. She stood outside of the machine, while offering kindness to those who are a part of it. I can hardly ever remember her angry. She was happy to accept each of us just as we are and treat each human being as a wonderful mystery.

MARY: Sarah was always doing good.

Sarah reminded me several times recently of a thing I did for her when she was about seven years old.

In Madison, Wisconsin, we lived in Mother’s dream house—a Tudor, with three bedrooms—a bedroom each for parents, boys, and girls. However, one of Mother’s goals for her family was for each of her children to have his or her own bedroom. Mother and Dad squeezed two additional bedrooms out of the basement furnace room. When Sarah (child number seven) was born, Chris and Paula each had a basement bedroom, three boys shared a room, and Sarah and I shared another. When Sarah was five, the family moved to Utah where the typical Utah ranch home has three bedrooms upstairs and three down: a total of six bedrooms.

Chris moved out for college. Paula graduated early from high school and went to live with friends at community college. Mother could reach her goal for her children. Now each child could have an “own room.”

Soon, however, Paula moved home to attend BYU. Mother expressed aloud her sadness that two of her children would now need to share a room. Sarah reminded me several times recently that that’s when I piped up and volunteered to share a room with her, my baby sister.

Sarah told me my offer was a defining moment in her life—an older sister accepting a little sister into her space. I tried to clarify that I was not trying to be nice but that I seriously would rather have not been alone. It was Sarah doing me a favor.

All these years she has continued to cling to the thought I was serving her when really she was blessing me.

That’s Sarah.

PAULA: Sarah was full of love and life. She always had enough love to give anyone and everyone. She loved each person individually and so many as a group. Sarah was like the energizer bunny. She enjoyed people, nature, activities, crafts and a bewildering array of other interests. She had an appreciation for everything and everyone around her and wanted to do her part to make things even better.

After I had back surgery, I went to stay at my Dad’s house where Sarah took care of me in addition to caring for Dad. That meant extra laundry, cooking and help with all the other things I couldn’t do for myself then.

Sarah loved family. She was there with us creating memories of many special times.

The day before her accident she turned 53. We got together as sisters and had a good time celebrating with her and just being with each other.

I will miss Sarah.

CHRIS: My little sister Sarah was 5 years old when I went off to college. I barely remember her as a baby and a toddler. It was more than 20 years later when I got to know Sarah. After college, and her mission, in the mid-1990s, she came out to Massachusetts to live with us for a year. She quickly became a beloved aunt to my three children and an always-cheerful member of the household.

I was always suspicious that at first Sarah felt like a naive small-town girl in the big city. But she quickly made friends in the single adult ward and gained confidence in herself. It seemed to me that was an important time for Sarah to become convinced that there was not just one way to be a modern Mormon woman, but room for all types and especially for her to be just the way she wanted to be.

Because of that time in Belmont, Massachusetts, I got to be a big brother again. Sarah would call to process family events and to share things that mattered to her. I am waiting for her call now.

Life Sketch

Sarah Camilla Kimball Whisenant (1968 – 2021)

Sarah Camilla Kimball arrived on January 14, 1968, in Madison, Wisconsin, during the turbulent Viet Nam War era. Hers was somewhat of a celebrity birth. The interns at the hospital flocked to witness what they had never seen before – the birth of a 7th child! Evelyn Bee Madsen and Edward Lawrence Kimball happily welcomed Sarah into their family with her 6 siblings - Christian, Paula (Gardner), Mary (Dollahite), Miles, Jordan, and Joseph.

Sarah spent her first five years in Madison in the affectionate company of her parents and siblings. With them she climbed trees, made mazes with raked leaves, fed ducks, and ice skated on a little frozen pond her father created at the beginning of the winter freeze.

In 1973 Sarah and her family moved to Utah – first to Mapleton, then to Provo. There Sarah’s kindness and sunny temperament blossomed. Her many friendships flourished in the neighborhood and schools. She graduated from Provo High School in 1986. Sarah studied at what was then Utah Valley State College, at Brigham Young University, and at the University of Utah, eventually graduating from the University of Utah in Communications. She was also a certified massage therapist.

During college Sarah studied abroad in Vienna, Austria, where she began learning German. Sarah managed the Evelyn Apartments in Salt Lake City, learning useful skills before her mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints from 1992-1993 in Berlin, Germany. She loved the Gospel, the people of Germany, the culture and their language.

Sarah blessed many lives with her generous spirit and friendships. She worked for twenty years at the Orem Public Library, cheerfully greeting patrons at the front desk or helping behind the scenes repairing books – one of the many artisanal crafts she mastered. Those in her community and church congregations benefitted from her gifts. Among her callings she served as Primary President, Young Women’s President, and teacher. She especially enjoyed her stint as Young Women’s Camp Director.

Sarah married Kevin Dee Whisenant on April 28, 2008, in Salt Lake City. They were later sealed in the Salt Lake Temple. Their home was in Springville, Utah.

Sarah’s life demonstrated the interconnectedness of all of God’s children. Sarah was an avid family historian with her sisters Mary and Paula. She made joyful connections with anyone who could conceivably be considered a “cousin.” She was a particularly fun aunt to her many nieces and nephews.

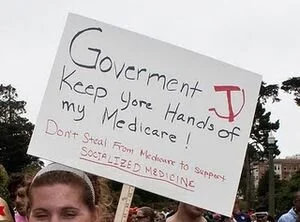

She was also an advocate for the disadvantaged and a promoter of racial justice and community service.

Sarah’s interest in “interconnectedness” was also quite literal. A lover of fiber and fiber crafts, Sarah was a member of Utah Valley Yarn Spinners in Utah Country for over two decades. She owned her own spinning wheel and loom and demonstrated weaving at historical and community events, including Constitution Day, the 4th of July, and Colonial Days – often in period costume. She also was skilled in knitting, quilting, ceramics, and upholstery.

Sarah’s know-how also included enviable practical skills. She remodeled a house down to the studs. She hired sub-contractors to teach her wiring, plumbing, and hanging sheetrock. She already knew trimming, painting, staining, and tiling. She assembled countless IKEA projects (including at least 2 kitchen remodels) that would stymy lesser souls.

Sarah was a life force of kindness, service, friendship, talent, good humor, and generosity. Her body succumbed to death January 23, 2021, in Murray, Utah, after injuries sustained during a car accident the previous week.

We celebrate her life of enthusiasm, curiosity, love, compassion and service.