Alexander Bogomolny: Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles →

Hat tip to Daniel Arovas. The link above leads to an array of links categorized by math topic and this explanation:

Back in 1996, Alexander Bogomolny started making the internet math-friendly by creating thousands of images, pages, and programs for this website, right up to his last update on July 6, 2018. Hours later on July 7th he passed away.

What Monetary Policy Can and Can't Do

Sluggish, Sticky, Inertial Inflation. There are two big problems with many academic models used to think about monetary policy. First, optimal monetary policy papers often do not include investment in the model. (See “Next Generation Monetary Policy.”) Second, a large share of all sticky price models lack any inflation inertia: if a substantial shock hit the model economy, inflation would instantly jump to a new and quite different value.

One model that does have inflation inertia in it is the model in Greg Mankiw and Ricardo Reis’s paper “Sticky Information Versus Sticky Prices: A Proposal to Replace the New Keynesian Phillips Curve.” The one big difference I have with Greg and Ricardo is that what they speak of as “sticky information” in their title, I think is not imperfect information, but imperfect information processing—something they should have emphasized. People can know things in some sense, but ignore them because the cost of meaningfully and appropriately using that information in decisions is high. (On the difference between imperfect information and imperfect information processing, see “Cognitive Economics.”)

In relation to the majority of macroeconomic models, one of the big mysteries of the Great Recession was why inflation didn’t fall more. In the last few years, one of the big mysteries for the majority of macroeconomic models has been why inflation didn’t rise more. Imperfect information processing is a likely part of the explanation for both: firms that believe that the Fed is trying hard to keep inflation at 2% might feel they don’t have to pay much attention to inflation. It is unlikely that they don’t know when inflation differs from 2% per year; they don’t do much with that information. Then what they do with their own prices tends to reproduce something much closer to 2% inflation than if they were paying attention to the level of inflation.

Let me summarize what I have said so far in this way: in the short-run, central banks cannot control inflation. In recent news, Jerome Powell confirmed this with his own frustration. In Nick Timiraos’s March 20, 2019 Wall Street Journal article “Fed Keeps Interest Rates Unchanged; Signals No More Increases Likely This Year,” Nick reports:

In a particularly revealing admission, Mr. Powell said he was discouraged that inflation hadn’t risen in a more sustainable fashion.

“I don’t feel we have convincingly achieved our 2% mandate in a symmetrical way,” he said. “It’s one of the major challenges of our time, to have downward pressure on inflation” globally.

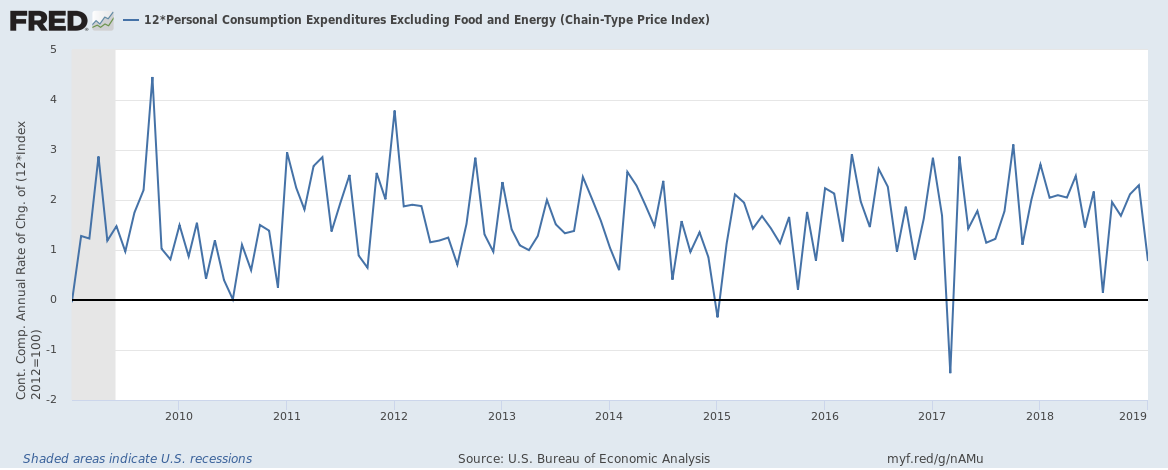

In other words, Jerome Powell, as Chair of the Federal Reserve Board and Chair of its interest-rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee, feels that inflation is changing much more slowly than he would like in response to Fed policy. The Fed has allowed the unemployment to fall below 4% for over a year now, and inflation according to the Fed’s favorite measure (the change in the deflator for personal consumption expenditures excluding food and energy) is lately still bouncing around between 1% and 2%, with an average of about 1.5%, instead of bouncing around between 1.5% and 2.5%, with an average of 2% as the Fed would like.

Personally, I have no doubt that low enough unemployment for long enough would cause inflation to begin increasing. But that is the long run. Leaving aside hyperinflationary situations that change at hyperspeed, in the short-run, central banks cannot control inflation.

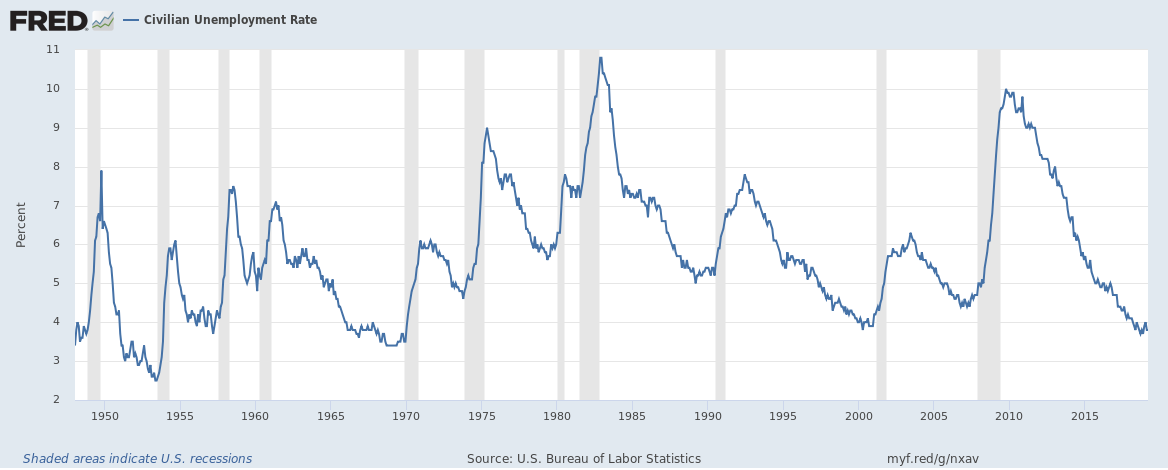

(To emphasize how dramatic the decline in unemployment has been since the depths of the Great Recession, take a look also at this graph of unemployment over a longer period of time:

)

The Classical Dichotomy. Let me now combine the idea that central banks cannot control inflation in the short run with the familiar idea that, simplifying only a little, in the long run central banks can only control inflation. Here, the “only” has a lot of poetic license to it: there are many other things that are closely related to inflation: the rate of increase in any nominal quantity, nominal interest rates, and real money balances. But by and large, all the important real quantities people care deeply about are unaffected by monetary policy in the long run. This is the “Classical Dichotomy” (which I consider to hold in the long-run, but not the short-run). In particular, monetary policy cannot affect the real interest rate in the long run. It is possible that claim is false, but it comes from absolutely standard economic theory—theory that makes sense to me.

How Inertial Inflation Simplifies the Fisher Equation Over Short Horizons. One consequence of how much inertia there is to inflation (in non-hyperinflationary situations), is that over a horizon of a year or two, there isn’t much difference between actual and expected inflation in the Fisher equation. So we can think of the ex ante real interest rate E r as being close to the ex post real interest rate and approximate by writing

r = i - pi

as the definition of the real interest rate, where

r = real interest rate

i = nominal interest rate

pi = inflation

(Ex ante is Latin for “before the fact,” and means the value expected in advance. Ex post is Latin for “after the fact,” and means what actually happens in the end—what one knows with hindsight.)

Eqivalently,

i = r + pi.

The Bottom Line. Putting everything together, let me summarize what central banks can and can’t do in the short run and in the long run:

In the short run, central banks can control the nominal interest rate i, and through it the real interest rate r, but can’t control inflation pi.

Through their control of the real interest rate in the short run, central banks can affect a large number of real variables in the short run.

In the long run, central banks can control inflation pi, and through it the nominal interest rate i, but can’t control the real interest rate r.

Because central banks can’t control the real interest rate in the long run, they can’t control any crucial real variable in the long run. (The biggest exception to the rule that central banks cannot affect real variables in the long run is that inflation and nominal interest rates influence real money balances.)

Update April 11, 2018: Lewis Lehe asks on Twitter:

Lewis: If they don’t affect inflation in the short run, couldn’t a central bank buy up, say, trillions worth of stocks and hold them for a year or so with no adverse consequence? Then the government could get all the dividends and not cause any inflation.

Miles: But while it can affect inflation only slowly, the effect on inflation that it does have is permanent.

This is part of a series of posts I am writing for my Intermediate Macroeconomics class this semester, including some that I wrote in advance. The others so far are:

John Cassidy: The High-Stakes Battle Between Donald Trump and the Federal Reserve →

The link above is to a New Yorker article that is a bit on the hyperventilating side. I think Donald Trump will lose this battle; so at this point there is no need for alarm. But the fact that Donald wants to weaken the independence of the Fed is to his discredit. If Donald Trump thinks the Fed makes too many mistakes in the direction of tightness, a good appointment now would be a Market Monetarist. By contrast, appointing—or trying to appoint—political hacks is destructive of the institution of the Fed.

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

157 minutes to listen the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes debate on Joe Rogan’s podcast is a bit much for me right now. If you want to see the video of the whole podcast yourself, here it is:

However, I did read Layne Norton’s review of the debate, shown at the top. Let me engage with the scientific issues Layne raises. I want to be clear that I am not in this post defending or attacking anything that Stephan Guyenet or Gary Taubes said or didn’t say in the podcast itself. I’ll only be talking about my own views and Layne’s views as he expressed them in his review.

Evidence on the Effect of Insulin on Calories Out. The biggest criticism I have of what Layne says is that he repeatedly acts as if the energy balance or “calories in/calories out” identity were a theory. It only becomes a theory once you specify what determines calories in and calories out. On what determines calories in “in the wild” of people’s actual lives, the metabolic ward studies that Layne refers to repeatedly are uninformative, because they carefully control the amount of calories people consume. On what determines calories out, metabolic ward studies can provide some evidence on purely metabolic effects, Layne doesn’t address the study I discuss in “Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories.” The other effect on calories out is how energetic one feels and therefore how much activity one does. Metabolic ward studies are also not great at showing these effects to the extent that not many activities are available while confined in the metabolic ward. And these studies might often try to standardize the activities of subjects in the studies.

One clue to a problem with the studies that Layne cites is this passage:

He would also likely point out that there was a small increase in energy expenditure on the ketogenic diet (that was near the detection limits of the equipment analyzing it). This difference in energy expenditure was transient during the first week of the ketogenic diet and didn’t last past that and didn’t produce meaningful differences in fat loss. This small increase in initial energy expenditure may likely be from the adaptation period of moving to use ketones & fats for fuels vs. carbohydrate. After that initial adaptation to ketones & fats, the small difference in energy expenditure disappears. In fact, it appears that when calories are equated, fat restriction may produce greater loss of body fat than carb restriction by a small amount.

Since any signal from each subject combined with a large enough sample can overcome any amount of uncorrelated noise, “near the detection limit” is a hint that a study is underpowered statistically. Nothing should be called “small” simply on the basis of having a low level of statistical significance in a small sample. And nothing should be called “small” if it could possibly cause, say, the pound a year weight gain of many American adults that is a description of much of the rise in obesity.

The fact that obesity comes on as slowly as it does for many people means that metaphors about fat being locked in cells (which I have used myself—see “How Low Insulin Opens a Way to Escape Dieting Hell”) when insulin levels are high must be taken as an indicator of direction, not as absolute statements. Layne makes the point I am making nicely in the following passage:

Now we have 2 central themes of the CIM with extremely strong evidence to the contrary. Let’s examine this notion that insulin is a magical fat storing hormone. Gary focuses on short term effects of insulin after a meal on fat storage (particularly around 2:09:35). Yes, insulin drives free fatty acids into cells, but assuming this is the cause of obesity takes a very simplistic view of adipose cell metabolism. Fat is constantly being stored into adipose and released from adipose. It is the net synthesis of fat minus the breakdown of fat in adipose that will determine fat balance and net fat loss or gain (I’m simplifying the model here but it’s accurate for our purposes).

Insulin doesn’t have to inhibit the release of fat from fat cells completely to be an important enough obstacle to fat burning to have a long-run effect. And if insulin levels, while not completely stopping fat burning, inhibit fat burning enough to lead in the long-run to weight gain, it could usefully be called a magical fat storing hormone.

How the Carbohydrate-Insulin Model Works. Let me now turn to what I find Layne’s most interesting paragraph. It’s first sentence is:

Hopefully, you’re convinced that part of the CIM [Carbohydrate-Insulin Model] is not plausible (calories don’t matter only carbs), but we can also rebuke other aspects of it.

There are two ideas here. It would be silly if the Carbohydrate-Insulin Model said that “calories don’t matter.” Calories are part of the causal pathway, the point of the Carbohydrate-Insulin model is that—even focusing on biology apart from psychology—calories are not the beginning of the causal pathway. As I interpret it, the Carbohydrate-Insulin Model emphasizes that—especially for those of us who aren’t in metabolic wards—calories are endogenous; therefore one should focus on the hormonal forces that drive calories in and calories out, rather than immediately jumping to trying to directly control calories in and calories out, as many people attempt to do.

Calories do matter, but the weight-loss strategy most people in our culture follow when they fixate on calories is usually a failure. Focus on eating low on the insulin index and on when you eat and calories in/calories out is likely to move in a direction that leads to weight loss without your directly thinking about calories. (See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” and “Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts.”) Once you have moved to low-insulin-index eating and a short eating window each day, you might want to experiment with thinking about the number of calories you are eating, but thinking about how much you eat should definitely come only third after thinking about what you eat and when you eat.

The reason to focus first on what you eat and when you eat and only then on how much you eat is that your body has decent mechanisms for controlling how much you eat at a sitting when you are eating healthy things, and how much you eat at a sitting puts a reasonable limit on how much you eat overall if you aren’t eating all the time.

Does Insulin Lock Fat in Fat Cells? The remainder of Layne’s most interesting paragraph is:

The idea that insulin traps free fatty acids in cells making the other tissues feel like they are “starving” has also been demonstrated to be incorrect. If this was correct, we would expect to see depleted levels of free fatty acids in blood during fasting in insulin resistant people. But we don’t. Obese people release MORE fatty acids from adipose, not less.

This is not a good argument on Layne’s part. As soon as one recognizes that even fairly high insulin levels do not completely lock fat in fat cells (even though insulin has an effect in that direction), it becomes obvious that number and size of fat cells is a factor in how much fat gets out into the bloodstream as well as insulin levels. So one should compare blood levels of fatty acids during fasting of people who have the same weight and amount of body fat but different levels of insulin to see the extent to which insulin goes in the direction of locking fat in fat cells.

Does Locking Fat in Fat Cells Leave the Rest of the Body Feeling Starved? But wait, Layne has an argument that even if fat is locked in fat cells, that doesn’t lead to hunger that causes one to eat more:

Hold on though, I’m not done crushing the CIM. Remember that one of the core themes of the CIM is that insulin causes fat to be trapped in fat cells and thus we can’t burn it and it’s not accessible to the other tissues of the body so we end up overeating because the rest of our tissues are “starving.” This aspect of the CIM has also been tested (indirectly) using a drug called acipimox which inhibits release of fats from adipose tissue. Not only did the subjects taking the drug not get fatter but they also did not increase their caloric consumption relative to the placebo group. [8: Makimura, H., Stanley, T. L, et. al. (2016, March). Metabolic Effects of Long-Term Reduction in Free Fatty Acids With Acipimox in Obesity: A Randomized Trial. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26691888]

The problem with this argument is that the people in this this Acipimox trial were eating freely, which for most Americans means eating almost all the time. If you are getting plenty of sugar and fats in your bloodstream from food you have just eaten, you don’t need fat from your fat cells in order to keep hunger at bay. It is when trying to lose weight that having plenty of fatty acids in the bloodstream from your fat stores is crucial for not feeling hungry. My prediction is that taking Acipimox would make it more painful to fast and more painful to try to lose weight when using the common strategy of reducing calories while keeping one’s schedule of eating unchanged. It is a very different experiment to see if Acipimox gets in the way of attempts at weight loss than whether it causes weight gain.

The study claimed benefits of Acipimox. Such benefits are reasonably plausible: if one is eating enough that the fatty acids in the bloodstream from one’s own fat cells wouldn’t (on net) get used, those extra fatty acids are not really helpful and might have some undesirable side effects.

One of my most important contentions is that insulin above a certain level makes it painful to cut back on calories. So it is better to both stick to low-insulin-index foods and to go to the extreme for certain periods of cutting calories back to zero so that insulin levels go low enough that the gates are wide open for fat to come out of the fat cells. When you cut back on calories, you need energy resources from your fat cells to take up the slack, and high insulin levels interfere with that. A few calories of high-insulin-index foods could easily make you quite miserable on a low-calorie diet—much more miserable than you would be eating nothing at all. And far from being miserable, you might not suffer much at all eating nothing if the last things you ate before fasting was food that is low on the insulin index. (Fasting here means drinking water—and maybe unsweetened tea or coffee—but not eating food.)

Exercise. One place where both Layne and I disagree with Gary Taubes is this:

Gary also states in the debate that exercise doesn’t really matter (see 1:42:10). If that was the case, where are all the fat marathon runners who eat high carb diets? Where are all the pro athletes gaining massive amounts of weight on high carb diets?

I said my piece on exercise in last Tuesday’s post: “On Exercise and Weight Loss.” The most relevant point there is that exercise is very valuable for avoiding gaining weight, but much less helpful for losing weight.

Gary Taubes. When I listen to most people, including Gary Taubes, I habitually try to turn what they are saying into the strongest version of the argument that I can come up with. Then I focus on my version of the argument. That makes me value people who have a take on things that provokes useful thoughts. Gary Taubes is one of those people. I can see that he might be frustrating to people who, instead of taking his arguments and improving on them, can only see his arguments as stated. I have yet to meet anyone who is right all the time or anyone who is wrong all the time. But I feel that Gary’s ideas are in a very useful direction—a direction that can be converted into testable science by those whose business it is to turn rough ideas into testable science.

Update, April 9, 2019: Layne Norton and other respond on this Twitter thread.

Layne Norton: good attempt at a rebuttal I guess. But your point about low carb causing greater energy expenditure and that @KevinH_PhD 's may have been underpowered (not based on previous data) ignores the other 30 studies looking at the same thing and actually slightly favoring low fat on EE

Kevin Hall: Our ketogenic diet study was powered to detect a 150 kcal/d effect size for the primary outcome. This was pre-specified in the protocol to be the minimum physiologically important effect on 24hr EE & signed-off by @NuSIorg. The null result led to shifting goalposts by @garytaubes

Sarong Joshi: If the bmj study is correct and LC increases metabolic rate And majority of hunter gatherers for majority of the part were low carbers And if optimum foraging strategy is correct That would just mean LC has least return on investment, evolution would've wiped out low carbers

I should say that, whatever Gary Taubes said, something less than 150 “calories” (technically, the usual calorie is a “kilocalorie”) a day, say 100 calories a day, is still an important effect. (Sarong’s argument is robust to that point.)

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography. I defend the ability of economists like me to make a contribution to understanding diet and health in “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’.”

Even a Just War Cannot Make It Right to Govern without the Consent of the Governed or to Dispossess Those in Conquered Territory

In the first two sections of Chapter XVI of John Locke’s 2d Treatise on Government: Of Civil Government, “Of Conquest,” he makes the easy case that “An Unjust War Cannot Win Any True Right to Rule,” as I wrote about two weeks ago. In the remainder of Chapter XVI, John Locke makes the more complicated case that a just war cannot make it right to govern without the consent of the governed or to dispossess those in conquered territory.

This puts John Locke on the other side of the argument from Bibi Netanyahu. Bibi hopes to have his coalition prevail again so he can be the Prime Minister of Israel for the fifth time. If he gets a fifth term, he says he will apply Israeli sovereignty to big chunks of the West Bank, to bit a little Israeli settlements that are now there. Bibi’s justification is especially interesting. Felicia Schwartz reports this in her April 6, 2019 Wall Street Journal article “Netanyahu Says He Will Extend Israeli Sovereignty Over West Bank If Re-Elected”:

In recent weeks, Mr. Netanyahu has become more strident in speaking about lands seized in the 1967 war, saying territory taken in a defensive war need not be returned.

This makes it sound as if states own territory that is, in fact, land owned by people—people whose consent must be obtained to make governing them legitimate.

To be clear, John Locke recognizes the virtue of recognizing a status quo that keeps conflict down. But if conflict is unavoidable—as it is in a defensive war—and previous political arrangements fall apart in some region, or need to be deconstructed because they led to aggression, then it is reasonable for a government that is still intact or a political entrepreneur to seek the consent of those in the area where previous political arrangements have fallen apart. Thus, Israel could legitimately have tried to win the hearts and minds of those resident in the West Bank and Gaza to become part of Israel. Alternatively, it could have tried to encourage a political entrepreneur to organize the West Bank and Gaza in a way that would be nonthreatening to Israel. Letting all of those in the conquered territories is undesired by the government of Israel because it would change the political equilibrium too much with that many new citizens with different views. And getting a peaceful democratic government in place in the conquered territories seems difficult to the point of near impossibility.

Barring being able to get a democratic government in place in the conquered territories that leaves Israel safe, good arguments can be made that Israel is justified in keeping a security presence when the government of a nearby territory repeatedly attacks. Finally, if residents of the West Bank, feeling 100% confident of their property rights, with no coercion whatsoever, chose to voluntarily sell land to Israeli settlers, the government of Israel would then need to seek the consent of those Israeli landowners if it wanted to govern that territory.

But in all cases, it is the consent of the governed that gives the right to rule, not conquering—even if that conquering is in a just war. Conquering a territory is more like the situation in a constitutional monarchy in which the king asks someone to attempt to form a government. The government must still be voted in: in that system the nomination by the king of someone to try to get together a majority coalition does not give one the right to rule; actually getting together the majority coalition gives one the right to rule.

Leaders who started a war of aggression can be punished severely, and underlings can be punished for war crimes and other rights violations. But those in the conquered territories who voted against conducting the war of aggression or were not allowed any say about the decision, and did as little as possible to further the war, and committed no rights violations, retain their full rights. (Here there is an important and difficult question about exactly how much attempted coercion one is expected to endure to avoid aiding an unjust war or committing rights violations of a certain gravity.)

John Locke’s argument that even a just war cannot make it right to govern without the consent of the governed or to dispossess those in conquered territory is very difficult to wade through, but its relevance to Israel’s situation makes it worth the trouble. Try to keep slogging through.

John Locke’s Argument

Let’s imagine a just war—say a defensive war. John Locke begins by saying that the leader of a victorious country in a just war still has to seek the consent of those in the conquering army and the rest of the people in the victorious country.

§. 177. But supposing victory favours the right side, let us consider a conqueror in a lawful war, and see what power he gets, and over whom. First, It is plain he gets no power by his conquest over those that conquered with him.They that fought on his side cannot suffer by the conquest, but must at least be as much freemen as they were before. And most commonly they serve upon terms, and on condition to share with their leader, and enjoy a part of the spoil, and other advantages that attend the conquering sword; or at least have a part of the subdued country bestowed upon them. And the conquering people are not, I hope, to be slaves by conquest, and wear their laurels only to shew they are sacrifices to their leader’s triumph. They, that found absolute monarchy upon the title of the sword, make their heroes, who are the founders of such monarchies, arrant Drawcansirs, and forget they had any officers and soldiers that fought on their side in the battles they won, or assisted them in the subduing, or shared in possessing, the countries they mastered. We are told by some, that the English monarchy is founded in the Norman conquest, and that our princes have thereby a title to absolute dominion: which if it were true, (as by the history it appears otherwise) and that William had a right to make war on this island: yet his dominion by conquest could reach no farther than to the Saxons and Britons, that were then inhabitants of this country. The Normans that came with him, and helped to conquer, and all descended from them, are freemen, and no subjects by conquest; let that give what dominion it will. And if I, or any body else, shall claim freedom, as derived from them, it will be very hard to prove the contrary: and it is plain, the law, that has made no distinction between the one and the other, intends not there should be any difference in their freedom or privileges.

If there is enough intermarriage between the people of the victorious, conquering country and those in the conquered country, soon, this principle alone goes a long way to make clear that conquest does not give one the right to be a dictator.

John Locke then goes on to talk about punishing the leaders of those that started the war of aggression, who are now conquered. His ideas on punishment do not match modern ideas, but the basic idea that the leaders of a country that begins an unjust war can be punished is sound:

§. 178. But supposing, which seldom happens, that the conquerors and conquered never incorporate into one people, under the same laws and freedom; let us see next what power a lawful conqueror has over the subdued: and that I say is purely despotical. He has an absolute power over the lives of those who by an unjust war have forfeited them; but not over the lives or fortunes of those who engaged not in the war, nor over the possessions even of those who were actually engaged in it.

Those beneath the leaders have a duty to resist the unjust war and any other rights violations. How far that duty goes is a difficult question, but enthusiastically helping leaders leading an unjust war is not fulfilling that duty:

§. 179. Secondly, I say then the conqueror gets no power but only over those who have actually assisted, concurred, or consented to that unjust force that is used against him: for the people having given to their governors no power to do an unjust thing, such as is to make an unjust war, (for they never had such a power in themselves) they ought not to be charged as guilty of the violence and injustice that is committed in an unjust war, any farther than they actually abet it: no more than they are to be thought guilty of any violence or oppression their governors should use upon the people themselves, or any part of their fellow-subjects, they having impowered them no more to the one than to the other. Conquerors, it is true, seldom trouble themselves to make the distinction, but they willingly permit the confusion of war to sweep all together: but yet this alters not the right; for the conqueror’s power over the lives of the conquered, being only because they have used force to do, or maintain an injustice, he can have that power only over those who have concurred in that force; all the rest are innocent; and he has no more title over the people of that country, who have done him no injury, and so have made no forfeiture of their lives, than he has over any other, who, without any injuries or provocations, have lived upon fair terms with him.

The appropriateness of punishing the leaders of the country that started the unjust war does not mean one can punish their families. If the families were enriched by ill-gotten gains, surely it is OK to take those away and use those riches to make restitution to those who were harmed. And making restitution for war damage from the possessions of a leader will almost unavoidably hurt the family of the leader. But much of this restitution will be to those who were part of the now conquered country that began a war of aggression. And John Locke argues that the damage done to the now victorious country and its citizens is unlikely to be enough to justify large-scale dispossession of large numbers of people as reparations. John Locke emphasizes how much land is likely to be worth compared to the value of the damages from a war. I would emphasize the human capital an individual has—which if the innocent son of a leader rather than the leader, cannot justly be taken away.

§. 180. Thirdly, The power a conqueror gets, over those he overcomes in a just war, is perfectly despotical: he has an absolute power over the lives of those, who by putting themselves in a state of war, have forfeited them; but he has not thereby a right and title to their possessions. This I doubt not, but at first sight will seem a strange doctrine, it being so quite contrary to the practice of the world; there being nothing more familiar in speaking of the dominion of countries, than to say such an one conquered it: as if the conquest, without any more ado, conveyed a right of possession. But when we consider, that the practice of the strong and powerful, how universal soever it may be, is seldom the rule of right, however it be one part of the subjection of the conquered, not to argue against the conditions cut out to them by the conquering sword.

§. 181. Though in all war there be usually a complication of force and damage, and the aggressor seldom fails to harm the estate, when he uses force against the persons of those he makes war upon, yet it is the use of force only that puts a man into the state of war: for whether by force he begins the injury, or else having quietly, and by fraud, done the injury, he refuses to make reparation, and by force maintains it, (which is the same thing, as at first to have done it by force) it is the unjust use of force, that makes the war: for he that breaks open my house, and violently turns me out of doors; or having peaceably got in, by force keeps me out, does in effect the same thing; supposing we are in such a state, that we have no common judge on earth, whom I may appeal to, and to whom we are both obliged to submit: for of such I am now speaking. It is the unjust use of force then, that puts a man into the state of war with another; and thereby he that is guilty of it makes a forfeiture of his life: for quitting reason, which is the rule given between man and man, and using force, the way of beasts, he becomes liable to be destroyed by him he uses force against, as any savage ravenous beast, that is dangerous to his being.

§. 182. But because the miscarriages of the father are no faults of the children, and they may be rational and peaceable, notwithstanding the brutishness and injustice of the father; the father, by his miscarriages and violence, can forfeit but his own life, but involves not his children in his guilt or destruction. His goods, which nature, that willeth the preservation of all mankind as much as is possible, hath made to belong to the children to keep them from perishing, do still continue to belong to his children: for supposing them not to have joined in the war, either through infancy, absence, or choice, they have done nothing to forfeit them: nor has the conqueror any right to take them away, by the bare title of having subdued him that by force attempted his destruction; though perhaps he may have some right to them, to repair the damages he has sustained by the war, and the defence of his own right; which how far it reaches to the possessions of the conquered, we shall see by-and-by. So that he that by conquest has a right over a man’s person to destroy him if he pleases, has not thereby a right over his estate to possess and enjoy it: for it is the brutal force the aggressor has used, that gives his adversary a right to take away his life, and destroy him if he pleases, as a noxious creature; but it is damage sustained that alone gives him title to another man’s goods: for though I may kill a thief that sets on me in the highway, yet I may not (which seems less) take away his money, and let him go: this would be robbery on my side. His force, and the state of war he put himself in, made him forfeit his life, but gave me no title to his goods. The right then of conquest extends only to the lives of those who joined in the war, not to their estates, but only in order to make reparation for the damages received, and the charges of the war, and that too with reservation of the right of the innocent wife and children.

§. 183. Let the conqueror have as much justice on his side, as could be supposed, he has no right to seize more than the vanquished could forfeit: his life is at the victor’s mercy; and his service and goods he may appropriate, to make himself reparation; but he cannot take the goods of his wife and children; they too had a title to the goods he enjoyed, and their shares in the estate he possessed: for example, I in the state of nature (and all commonwealths are in the state of nature one with another) have injured another man, and refusing to give satisfaction, it comes to a state of war, wherein my defending by force what I had gotten unjustly, makes me the aggressor. I am conquered: my life, it is true, as forfeit, is at mercy, but not my wife’s and children’s. They made not war, nor assisted in it. I could not forfeit their lives; they were not mine to forfeit. My wife had a share in my estate; that neither could I forfeit. And my children also, being born of me, had a right to be maintained out of my labour or substance. Here then is the case: the conqueror has a title to reparation for damages received, and the children have a title to their father’s estate for their subsistence: for as to the wife’s share, whether her own labour or compact, gave her a title to it, it is plain, her husband could not forfeit what was her’s. What must be done in the case? I answer; the fundamental law of nature being, that all, as much as may be, should be preserved, it follows, that if there be not enough fully to satisfy both, viz. for the conqueror’s losses, and children’s maintenance, he that hath, and to spare, must remit something of his full satisfaction, and give way to the pressing and preferable title of those who are in danger to perish without it.

§. 184. But supposing the charge and damages of the war are to be made up to the conqueror, to the utmost farthing; and that the children of the vanquished, spoiled of all their father’s goods, are to be left to starve and perish: yet the satisfying of what shall, on this score, be due to the conqueror, will scarce give him a title to any country he should conquer: for the damages of war can scarce amount to the value of any considerable tract of land, in any part of the world, where all the land is possessed, and none lies waste. And if I have not taken away the conqueror’s land, which, being vanquished, it is impossible I should; scarce any other spoil I have done him can amount to the value of mine, supposing it equally cultivated, and of an extent any way coming near what I had over-run of his. The destruction of a year’s product or two (for it seldom reaches four or five) is the utmost spoil that usually can be done: for as to money, and such riches and treasure taken away, these are none of nature’s goods, they have but a fantastical imaginary value: nature has put no such upon them: they are of no more account by her standard, than the wampompeke of the Americans to an European prince, or the silver money of Europe would have been formerly to an American. And five years product is not worth the perpetual inheritance of land, where all is possessed, and none remains waste, to be taken up by him that is disseized; which will be easily granted, if one do but take away the imaginary value of money, the disproportion being more than between five and five hundred; though, at the same time, half a year’s product is more worth than the inheritance, where there being more land than the inhabitants possess and make use of, any one has liberty to make use of the waste: but there conquerors take little care to possess themselves of the lands of the vanquished. No damage therefore, that men in the state of nature (as all princes and governments are in reference to one another) suffer from one another, can give a conqueror power to dispossess the posterity of the vanquished, and turn them out of that inheritance, which ought to be the possession of them and their descendants to all generations. The conqueror indeed will be apt to think himself master: and it is the very condition of the subdued not to be able to dispute their right. But if that be all, it gives no other title than what bare force gives to the stronger over the weaker: and, by this reason, he that is strongest will have a right to whatever he pleases to seize on.

In Section 185, John Locke makes a nice summary of his argument up to that point:

§. 185. Over those then that joined with him in the war, and over those of the subdued country that opposed him not, and the posterity even of those that did, the conqueror, even in a just war, hath, by his conquest, no right of dominion: they are free from any subjection to him, and if their former government be dissolved, they are at liberty to begin and erect another to themselves.

Some conquerors try to claim they have received the consent of the conquered when that supposed consent is made under coercion:

§. 186. The conqueror, it is true, usually by the force he has over them, compels them, with a sword at their breasts, to stoop to his conditions, and submit to such a government as he pleases to afford them; but the enquiry is, what right he has to do so? If it be said, they submit by their own consent, then this allows their own consent to be necessary to give the conqueror a title to rule over them. It remains only to be considered, whether promises extorted by force, without right, can be thought consent, and how far they bind. To which I shall say, they bind not at all; because whatsoever another gets from me by force, I still retain the right of, and he is obliged presently to restore. He that forces my horse from me, ought presently to restore him, and I have still a right to retake him. By the same reason, he that forced a promise from me, ought presently to restore it, i. e. quit me of the obligation of it; or I may resume it myself, i. e. chuse whether I will perform it: for the law of nature laying an obligation on me only by the rules she prescribes, cannot oblige me by the violation of her rules: such is the extorting any thing from me by force. Nor does it all alter the case to say, I gave my promise, no more than it excuses the force, and passes the right, when I put my hand in my pocket, and deliver my purse myself to a thief, who demands it with a pistol at my breast.

§. 187. From all which it follows that the government of a conqueror, imposed by force on the subdued, against whom he had no right of war, or who joined not in the war against him, where he had right, has no obligation upon them.

John Locke returns to the innocence of children in the conquered country. Even though that country was conquered in a just war, innocent children have not forfeited any of their rights:

§. 188. But let us suppose, that all the men of that community, being all members of the same body politic, may be taken to have joined in that unjust war wherein they are subdued, and so their lives are at the mercy of the conqueror.

§. 189. I say, this concerns not their children who are in their minority: for since a father hath not, in himself, a power over the life or liberty of his child, no act of his can possibly forfeit it. So that the children, whatever may have happened to the fathers, are freemen, and the absolute power of the conqueror reaches no farther than the persons of the men that were subdued by him, and dies with them: and should he govern them as slaves, subjected to his absolute arbitrary power, he has no such right of dominion over their children. He can have no power over them but by their own consent, whatever he may drive them to say or do, and he has no lawful authority, whilst force, and not choice, compels them to submission.

What are the rights of those innocent children? First, each individuall has the right to be free. Second, John Locke has a complicated argument that they have a right to their ancestral land that cannot be altered by the laws of a government they collectively do not assent to.

§. 190. Every man is born with a double right: First, a right of freedom to his person, which no other man has a power over, but the free disposal of it lies in himself. Secondly, a right, before any other man, to inherit with his brethren his father’s goods.

§. 191. By the first of these, a man is naturally free from subjection to any government, though he be born in a place under its jurisdiction; but if he disclaim the lawful government of the country he was born in, he must also quit the right that belonged to him by the laws of it, and the possessions there descending to him from his ancestors, if it were a government made by their consent.

§. 192. By the second, the inhabitants of any country, who are descended, and derive a title to their estates from those who are subdued, and had a government forced upon them against their free consents, retain a right to the possession of their ancestors, though they consent not freely to the government, whose hard conditions were by force imposed on the possessors of that country: for the first conqueror never having had a title to the land of that country, the people who are the descendants of, or claim under those who were forced to submit to the yoke of a government by constraint, have always a right to shake it off, and free themselves from the usurpation or tyranny which the sword hath brought in upon them, till their rulers put them under such a frame of government, as they willingly and of choice consent to. Who doubts but the Grecian christians, descendants of the ancient possessors of that country, may justly cast off the Turkish yoke, which they have so long groaned under, whenever they have an opportunity to do it? For no government can have a right to obedience from a people who have not freely consented to it; which they can never be supposed to do, till either they are put in a full state of liberty to chuse their government and governors, or at least till they have such standing laws, to which they have by themselves or their representatives given their free consent, and also till they are allowed their due property, which is so to be proprietors of what they have, that nobody can take away any part of it without their own consent, without which, men under any government are not in the state of freemen, but are direct slaves under the force of law.

Even if the leader of a conquering country did own a conquered country lock, stock and barrel—which John Locke has been disputing—to create good incentives, he or she would need to bestow some property of some sort. That property then becomes subject to natural law. In particular, one of the most basic principles of natural law is that one must keep one’s promises when these are made freely. And the kind of leader we are talking about has so much power, that we know the promises are made freely:

§. 193. But granting that the conqueror in a just war has a right to the estates, as well as power over the persons, of the conquered; which, it is plain, he hath not: nothing of absolute power will follow from hence, in the continuance of the government; because the descendants of these being all freemen, if he grants them estates and possessions to inhabit his country, (without which it would be worth nothing) whatsoever he grants them, they have, so far as it is granted, property in. The nature whereof is, that without a man’s own consent it cannot be taken from him.

§. 194. Their persons are free by a native right, and their properties, be they more or less, are their own, and at their own disposal, and not at his; or else it is no property.Supposing the conqueror gives to one man a thousand acres, to him and his heirs for ever; to another he lets a thousand acres for his life, under the rent of 50l. or 500l. per ann. has not the one of these a right to his thousand acres for ever, and the other, during his life, paying the said rent? and hath not the tenant for life a property in all that he gets over and above his rent, by his labour and industry during the said term, supposing it be double the rent? Can any one say, the king, or conqueror, after his grant, may by his power of conqueror take away all, or part of the land from the heirs of one, or from the other during his life, he paying the rent? or can he take away from either the goods or money they have got upon the said land, at his pleasure? If he can, then all free and voluntary contracts cease, and are void in the world; there needs nothing to dissolve them at any time, but power enough: and the grants and promises of men in power are but mockery and collusion: for can there be any thing more ridiculous than to say, I give you and yours this for ever, and that in the surest and most solemn way of conveyance can be devised; and yet it is to be understood, that I have right, if I please, to take it away from you again to-morrow?

§. 195. I will not dispute now whether princes are exempt from the laws of their country; but this I am sure, they owe subjection to the laws of God and nature, Nobody, no power, can exempt them from the obligations of that eternal law. Those are so great, and so strong, in the case of promises, that omnipotency itself can be tied by them. Grants, promises, and oaths, are bonds that hold the Almighty: whatever some flatterers say to princes of the world, who altogether, with all their people joined to them, are, in comparison of the great God, but as a drop of the bucket, or a dust on the balance, inconsiderable, nothing!

John Locke’s argument is a complex one, so it good that he makes a finally summary:

§. 196. The short of the case in conquest is this: the conqueror, if he have a just cause, has a despotical right over the persons of all, that actually aided, and concurred in the war against him, and a right to make up his damage and cost out of their labour and estates, so he injure not the right of any other. Over the rest of the people, if there were any that consented not to the war, and over the children of the captives themselves, or the possessions of either, he has no power; and so can have, by virtue of conquest, no lawful title himself to dominion over them, or derive it to his posterity; but is an aggressor, if he attempts upon their properties, and thereby puts himself in a state of war against them, and has no better a right of principality, he, nor any of his successors, than Hingar, or Hubba, the Danes, had here in England; or Spartacus, had he conquered Italy, would have had; which is to have their yoke cast off, as soon as God shall give those under their subjection courage and opportunity to do it. Thus, notwithstanding whatever title the kings of Assyria had over Judah by the sword, God assisted Hezekiah to throw off the dominion of that conquering empire. “And the Lord was with Hezekiah, and he prospered; wherefore he went forth, and he rebelled against the king of Assyria, and served him not,” 2 Kings xviii. 7. Whence it is plain, that shaking off a power, which force, and not right, hath set over any one, though it hath the name of rebellion, yet is no offence before God, but is that which he allows and countenances, though even promises and covenants, when obtained by force, have intervened: for it is very probable, to any one that reads the story of Ahaz and Hezekiah attentively, that the Assyrians subdued Ahaz, and deposed him, and made Hezekiah king in his father’s life-time; and that Hezekiah by agreement had done him homage, and paid him tribute all this time.

1689, when the Second Treatise was published, is a long time ago. But in their application, the arguments are literally as current as yesterday’s news. I have read a lot about the situation in Israel and its conquered territories in my 58 years. I can say that John Locke’s arguments offers a fresher and deeper take on that situation than almost all the commentators I have read.

For links to other John Locke posts, see these John Locke aggregator posts:

Jonathan Mahler and Jim Rutenberg on Rupert Murdoch →

Rupert Murdoch is one of the most consequential people in the world. He is the head of a vast media empire. That media empire is not left-wing in its approach to news. The link above is to an in-depth article on Rupert Murdoch and his empire.

The Economist: Why is Chicken So Cheap?

This is a story of technological progress, as well as giving insight into issues that can raise ethical concerns. Hat tip to Joseph Kimball.

Supply and Demand for the Monetary Base: How the Fed Currently Determines Interest Rates

Before October 3, 2008, the interest rate the Fed paid on excess reserves was zero, because it was only on that date that the Fed received authority to pay a nonzero rate on excess reserves. Since for market equilibrium, it is the amount of interest paid on the last dollar of reservers that matters most, I will simplify by calling the interest rate on excess reservers simply the interest on reserves (IOR). As you can see from the top graph, during that period when the Fed was limited to an IOR of zero, the federal funds rate and the 3-month Treasury bill rate, while tracking each other, were often very different from the IOR.

The second graph shows that, more recently, the federal funds rate and the 3-month Treasury bill rate have not only tracked each other, but also move together with the IOR. What is going on? Let me lay out a very simple model of supply and demand for the monetary base to explain this.

“The monetary base” means the same thing as “high-powered money” and the same thing as “narrow money.” The monetary base is equal to reserves + paper currency and coins. Paper currency and coins stored in bank vaults counts as part of the monetary base, but only once: it must be counted either as reserves or as paper currency, but not both.

The Fed (or other central bank) is in complete control of the monetary base because the only thing that adds to the monetary base is when the Fed buys things; and other than the rare cases in which someone literally sets fire to paper currency, or destroys a coin, the only thing that reduces the monetary base is when the Fed sells things. (If paper currency or coins were permanently lost, it would probably still be counted as part of the monetary base, but in economic effects, this permanent loss of paper currency or coins would be like a reduction in the monetary base. On the other hand, when paper currency wears out, that is not a reduction in the monetary base, because people can take worn-out paper currency to the cash window of the central bank and get new paper currency in exchange.)

The Fed mostly buys assets, but it does some amount of buying goods and services. (For example, it pays salaries to its staff.) The main asset it buys are 3-month Treasury bills. (If the Fed buys any other asset besides 3-month Treasury bills or a derivative of 3-month Treasury bills it is called Quantitative Easing, or QE for short.) Similarly, the main thing the Fed sells is 3-month Treasury bills; it controls the amount of 3-month Treasury bills that it sells.

Because the Fed completely controls the quantity of the monetary base, I draw the supply curve for the monetary base as vertical:

From here on, I when I write “paper currency” I mean “paper currency and coins.” While the Fed controls the total quantity of the monetary base, given current paper currency policy the division of the monetary base between paper currency and reserves is totally up to the private sector. In “An Underappreciated Power of a Central Bank: Determining the Relative Prices between the Various Forms of Money Under Its Jurisdiction” I write about the “cash window” that in the US exists at each regional Federal Reserve Bank. Under current paper currency policy, commercial banks can freely exchange reserves in their reserve accounts for the same face value of paper currency or exchange paper currency for reserves in their reserve accounts equal to the face value of the paper currency that is deposited.

Because the monetary base consists of paper currency plus reserves, the demand for the monetary base comes from the demand for paper currency and the demand for reserves. A certain amount of paper currency and coins has relatively high value—which I measure as an annual rate of return on the vertical axis—for (a) convenience in transactions, (b) tax evasion and (c) other illegal activities. A certain amount of reserves has a relative high value—again measured as an annual rate of return—for (1) supporting required reserves and (2) providing excess reserves that banks feel they need for safety purposes. But at some point, the monetary base would be so large that just keeping the dollars as reserves earning the IOR is a better option than (a), (b), (c), (1) or (2). After that point, the value of an extra dollar of monetary base is simply the IOR. (I am abstracting from the situation in which massive paper currency storage is an attractive option—that is, when the official paper currency interest rate, which is traditionally set by policy to zero, minus storage costs, is an attractive return relative to the marginal value of monetary base for (a), (b), (c), (1) or (2). I have written a lot about how the Fed or other central bank should deal with the possibility of massive paper currency storage. See the links collected in “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”)

Putting everything together, at a large enough value of the monetary base, the demand for monetary base curve should be flat at the height of the IOR. Left of that point, the demand for monetary base curve should be higher. And the smaller the quantity of the monetary base the further up the value (=implicit rate of return) of a dollar of monetary base should be. That means that on the left side of the graph the demand for monetary base curve is downward-sloping, while on the right side of the graph, the demand for monetary base curve is flat at the height of the IOR.

To give the intuition in a slightly different way for why the demand for monetary base curve is downward sloping to the left, but flat to the right, the first few dollars of monetary base are very valuable. But at some point all of this higher rate of return is exhausted; the monetary base is large enough that banks and others see the value of the last dollar as only the ability of that dollar to earn the interest on reserves.

One subtle but useful point is that the demand for monetary base curve is really the vertical maximum over two curves that are determined separately. There is a downward sloping curve for the marginal value of a dollar in monetary base for uses (a), (b), (c), (1) or (2). Then there is a curve that is flat at the height of the IOR. Whichever is higher at any given quantity of monetary base rules the day. But these two pieces of the demand for monetary base curve move separately, “hiding” the part of the other curve that is underneath.

What do we learn from equilibrium between the supply and demand for the monetary base? The vertical level of equilibrium is the marginal value or rate of return of a dollar of monetary base. The federal funds rate is the rate at which commercial banks lend reserves to one another, so the federal funds rate should measure the marginal value or rate of return of a dollar of monetary base. And term structure relationships force a close alignment between the federal funds rate and the 3-month Treasury bill rate. These rates in turn affect many other interest rates in the economy. The Fed can control many interest rates in the economy in the short run by changing the height of the equilibrium of the supply and demand for the monetary base. Hence, I have labeled the vertical axis with the letter i, standing for the nominal interest rate (and in particular, a very short-term, very safe rate).

Historically, the Fed used to keep the monetary base small, so that the supply of monetary base intersected the demand curve for the monetary base at the downward-sloping part to the left. But since the 2008 Financial Crisis, the Fed increased the monetary base enough that the supply of the monetary base intersects the demand curve for the monetary base on the flat part to the right, like this:

At that point, the IOR was quite low, .25% per year. But recently, the Fed has increased the IOR, so that the current situation is like this:

(Notice how some of the downward-sloping part got hidden by the higher IOR.)

The striking thing from these last two graphs is the theory’s implication that when the monetary base us large enough, the IOR basically determines the level of other safe, short-term rates such as the federal funds rate and the 3-month Treasury bill rate. In the real world, things are complicated by the fact that only banks, and then only some banks, are allowed to have reserve accounts. So other financial firms that want to take advantage of the IOR have to go through banks that are allowed to have reserve accounts. Those banks take a cut, leaving the rest as a somewhat lower federal funds rate (which is closely tied by a term-structure relationship to the 3-month Treasury bill rate).

Recently (2019), in my interpretation of Fed news, the Fed has begun to make noises that it intends to keep the monetary base large enough that the supply of the monetary base continues to intersect the demand curve for the monetary base on the flat part to the right. That will keep the rate of return for monetary base very close to the interest on reserves (IOR), implying that the federal funds rate at which banks lend reserves to each other, the 3-month Treasury bill rate and the repo rate at which banks lend Treasury bills to one another will stay close to the interest rate on reserves (IOR). If those key interest rates (the federal funds rate is the Fed's target rate in the US) stay close to the interest on reserves (IOR), then one can view the interest on reserves (IOR) is the central tool for determining short-run safe rates. But the IOR is the central tool for determining short-run safe rates only in the context of the monetary base being kept large enough that the supply of the monetary base is to the right of the downward-sloping part of the demand for monetary base curve.

Here is the key passage behind that interpretation, from the unabridged version of Nick Timiraos’s March 2019 article “Fed Keeps Rates Unchanged, Signals No More Increases Likely This Year”:

On the asset-portfolio front, the Fed has been shrinking its $4 trillion in holdings since October 2017. While the runoff has slowly removed stimulus from the economy, officials have said the decision to end that runoff is being driven primarily by technical factors to make sure the central bank can smoothly implement its monetary policy decisions.

Any time the Fed buys “holdings” it adds to the monetary base, and anytime it sells “holdings” it reduces the monetary base. I interpret the phrase “technical factors to make sure the central bank can smoothly implement its monetary policy decisions” to mean that the Fed likes being on the flat part of the monetary base demand curve. (Let me mention that in my view, among current reporters on the Fed, Nick Timiraos is the best in the business.) Thus, it seems that an equilibrium in which the monetary base is large enough that the IOR is the key determinant of the level of short-term safe rates could be the new normal.

Besides the convenience and reliability of nailing down short-term safe rates with the IOR, which the Fed gets when it keeps the monetary base large, there is one other benefit to keeping the monetary base—and particularly reserves—large. At the 2016 Jackson Hole conference that I was luck enough to be invited to, Jeremy Stein presented his paper coauthored with Robin Greenwood and Samuel Hanson: “The Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet as a Financial-Stability Tool.” This paper argues, in effect, that if the Fed or some other arm of the government doesn’t provide enough short-term safe assets, that the demand for such assets will be high enough that private firms will create assets that pretend to be short-term safe assets, but aren’t—at least not in the same way reserves are. When the pretense unravels, people freak out, which can create or contribute to a financial crisis. For example, in the Financial Crisis that intensified toward the end of 2008, when it became clear that money market mutual fund shares that pretended to always be worth a dollar were actually worth less than a dollar, people freaked out. (This was called “breaking the buck.”) I was very impressed with this argument, and I suspect that, with some delay, other Fed officials were impressed with it as well. Jeremy Stein was himself on the Federal Reserve Board for a short time, and I’ll bet was well-respected by his colleagues. I wrote about Jeremy in my column “Meet the Fed's New Intellectual Powerhouse.” (Unfortunately, Jeremy stepped down from the Federal Reserve Board soon after I wrote this.)

What I have written above is what I now teach my students in my intermediate macro class about how the Fed determines interest rates operationally. It should be in macro textbooks, but for the most part isn’t yet.

Update, April 5, 2019: On the Facebook page for this post, Roc Armenter wrote: check the “normalization plans and principles” update of january 2019 for something more than “making noises”...

For other aspects of what I teach my students in my intermediate macro class, see “On Teaching and Learning Macroeconomics.” Also, don’t miss last week’s post, “The Costs of Inflation.” On the division of the monetary base into paper currency and reserves, some of you might be interested in the very heavy-duty post, “The Supply and Demand for Paper Currency When Interest Rates Are Negative.”

Update, March 22, 2020: I posted a related online lecture “Analyzing the Great Recession Using Supply and Demand for the Monetary Base.” This lecture uses facts about the Treasury bill rate at the beginning of the Great Depression from this graph:

On Exercise and Weight Loss

Many studies show that exercise is relatively ineffective for weight loss. (See the article I retitled in my flagging as “Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies.”) In this post, I want to give a possible theory about why. I will build on the idea that “Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon.”

I need the insulin-centric theory I will explore also to explain why exercise seems to be helpful in avoiding weight gain. On that score, exercise that increases muscle mass and more muscle tone means there is more muscle more ready to take up blood sugar when insulin signals that there is a surplus of blood sugar. That means a more modest insulin signal can get blood sugar back in line. The less insulin is needed to get blood sugar back in line, the less the fat cells hear an insulin signal that they should turn blood sugar into fat and store it. Furthermore, if insulin levels don’t go as high, neither the muscle cells nor the fat cells are as likely to develop partial “deafness” to insulin that leads to the insulin-producing cells “shouting.” That is, if insulin never gets too high in the first place, there is no reason for cells like the fat cells and muscle cells to develop insulin resistance, nor for insulin levels to become even more elevated in response.

What about weight loss? Let’s focus only on weight loss people are trying to achieve because they are genuinely overweight to begin with. In the insulin-centric theory, most people who are overweight to begin with became overweight because of elevated insulin levels over a long time. Thus, most people who are overweight have some degree of insulin resistance, and have insulin producing cells that have to do some amount of “shouting” in order to keep blood sugar in line. That makes it hard to get insulin low enough that fat cells will release their fat. The metaphor I use in “How Low Insulin Opens a Way to Escape Dieting Hell” is that levels of insulin that are hard for people with insulin resistance to get below are enough to lock fat inside fat cells. And remember the idea that most people who are overweight to begin with have insulin resistance.

What will happen when people with high enough insulin levels to lock fat inside their fat cells exercise? If they can’t get energy from their stored fat, then their blood sugar levels will get low, leading them to (a) feel tired, (b) get hungry, and (c) burn less energy when they go through the following non-exercise part of their day. Feeling tired may lead to quitting the exercise program. Getting hungry can easily lead to eating enough more to cancel out any energy burned from the exercise. And in subtle ways, activity levels and non-activity-related energy burning can ramp down during the non-exercise part of the day.

I said that getting below the critical level of insulin at which fat starts being released from fat cells is hard for most people who are overweight to begin with. What I meant was that it is hard if they continue to eat three meals a day. Shortening the eating window to 8 hours—say skipping breakfast and not eating after dinner—means that there are 16 hours for insulin levels to get low. For many people this will lead to substantial weight loss. If that isn’t enough, it is possible to experiment with fasting (not eating, but continuing to drink water) for longer periods of time. If you want to try that, read the cautions I have in “Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia.”

The key tip for those who want to shorten their eating window or go even further is that going without eating for 16 hours or more is much easier if when you do eat, you are eating foods that have a low index. On that, see “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid”and “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet.”

The short version is that if you don’t get your insulin levels low enough—which for people who are overweight usually requires changing the timing of your eating as well as what you eat—it will be very hard to lose weight because your body will fight you. (See “Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts.”) And that includes if you exercise.

There is accumulating evidence that shortening your eating window and otherwise having periods of fasting is good for your health in many ways. But even if you decide not to try that, and in the three-meal-a-day context exercise doesn’t lead to any weight loss, exercise can still help make you happier, healthier and smarter, and less likely to gain even more weight than you have already. So it is worth exercising no matter what.

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health:

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

David Ludwig: It Takes Time to Adapt to a Lowcarb, Highfat Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Other Health Issues

VII. Wonkish

Framingham State Food Study: Lowcarb Diets Make Us Burn More Calories

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Don't Tar Fasting by those of Normal or High Weight with the Brush of Anorexia

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

After Gastric Bypass Surgery, Insulin Goes Down Before Weight Loss has Time to Happen

A Low-Glycemic-Index Vegan Diet as a Moderately-Low-Insulin-Index Diet

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

Layne Norton Discusses the Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes Debate (a Debate on Joe Rogan’s Podcast)

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Eggs May Be a Type of Food You Should Eat Sparingly, But Don't Blame Cholesterol Yet

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography. I defend the ability of economists like me to make a contribution to understanding diet and health in “On the Epistemology of Diet and Health: Miles Refuses to `Stay in His Lane’.”

Teens are Too Suspicious for Anything But the Truth about Drugs to Work

Link to the article above

In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell tells the story of a very promising proto-campaign against teen smoking that took advantage of teenagers’ desire to show their independence of the norms of adult society. The ads highlighted how tobacco executives lie and deceive, so that not smoking is a way to stick it to the Man. Why would you want to smoke when evil liars are trying to get you to?

In Malcolm Gladwell’s story, the campaign never got off the ground because it was deemed too offensive to tobacco executives. But this story showcases the importance of telling teens something they will actually believe when you are trying to get them to do something. Teenagers are wired to be alert to the possibility that their interests might diverge from the interests of the adults who are trying to get them to do or not do something. This makes it difficult to get teens to do something by giving them a slanted account of how the world works. That slanted account won’t ring true and will be discounted.

Tobacco, alcohol, marijuana and illegal drugs, like almost everything, have both pluses and minuses. Most teens won’t believe you if you say drugs only have minuses. And if you exaggerate the harms, then one or two cases of friends taking drugs without apparent harm can falsify your portrayal.

David Scheff, in the essay shown above, gives these measured things to say about legal and illegal drugs (all eight quotations are from his essay shown above, “Teens Need the Truth About Drugs”):

Nine out of 10 people who become addicted tried drugs before the age of 18

About 17% of teenagers who smoke [marijuana] develop substance-use disorders, according to two Cambridge University studies.

… most adolescents who drink won’t become alcoholics, but according to research by the National Academy of Medicine, 15% will.

Teenagers with blood-alcohol content of .08% are 17 times more likely to die in a car crash, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

… brains are changing more in youth and adolescence than they ever will again and that drug use at their age can hurt that development. Drugs really do change the brain, which is a big reason that people take them. But while some changes are temporary, others can be permanent.