Prevention is Much Easier Than Cure of Obesity

Given patience and fortitude at the beginning, what is needed for curing obesity can become easy—in steady state. The basic argument for that is in my post "4 Propositions on Weight Loss." But the steps needed to cure obesity are not an easy path. Prevention is much easier.

Prevention

The scientific verdict has not been delivered, but as a hypothesis I have mentioned before, I see two things that plausibly have the right timing to explain the worldwide rise in obesity:

- The rise of sugar, flour, and modern processed foods.

- The likely expansion of the daily eating window from, say, 10 hours (for example, 8 AM to 6 PM) to almost 16 hours (from right after waking to right before sleeping).

The kind of work economic historians do devoted to finding and analyzing data that can speak to patterns of what and when people ate 100 to 150 years ago could be golden in scrutinizing this hypothesis. As I urge in "Defining Economics,"

... economists ought to tackle the full range of problems that human capital gives them a comparative advantage at tackling. In my view, that includes a large share of all the big questions in the social sciences, and may include big questions in other areas (say, non-experimental studies of the effects of nutrition) that call for a level of statistical sophistication in dealing with messy situations that is not easy to obtain outside of economics PhD programs.

As applied to today, this hypothesis boils down to the hypothesis that if

- you stay away from sugar during pregnancy (or your child's mother does),

- keep your kids from eating sugar thereafter,

- successfully discourage snacking after dinner, and

- get them to internalize these as good habits they continue after they leave home,

then your children are unlikely to have a problem with obesity in their lives. Note that almost all processed foods have a fair bit of sugar in them; therefore, as things stand, staying away from sugar implies staying away from processed food. If there is something else bad about processed food, that is handled.

Let me also put forward the related, but distinct hypothesis that if

- throughout your life so far, you have always been relatively thin (say a BMI—Body Mass Index—of 23 or below), and

- you avoid sugar and keep to an eating window of no more than 10 hours on a typical day going forward,

you are unlikely to have a problem with obesity in your life. I am also willing to predict that these habits will help avoid having the kinds of diseases that are associated with obesity strike you even if you remain thin.

Cure

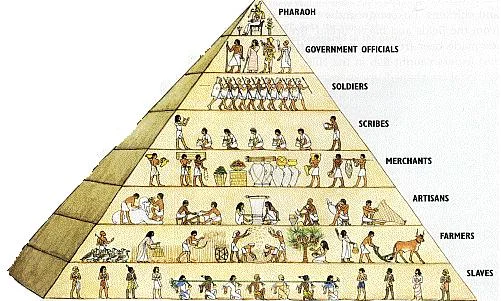

Unfortunately, the cure once your system is messed up enough for you to have become overweight is much more difficult. There may be many dimensions of "messing up your system." The one I know about is becoming insulin-resistant. (See "Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon.") I understand this to be a continuous variable: it is possible to be a little bit insulin-resistant, below what would lead to a diagnosis of insulin resistance. But every bit of insulin resistance makes it easier to put your body in the state where it accumulates body fat and harder to put your body in the state where it reduces body fat. There may be other mechanisms I don't know about that have the same effect. There are also equilibrating mechanisms that (other things equal) tend to make losing weight easier if your weight is high and gaining weight easier if your weight is low. Together all of these mechanisms constitute what might justifiably be called a "fat thermostat" that gets set higher the more your system is messed up. (The term "fat thermostat" was used by some popular diet books in the 80s and 90s.)

In any case, it is common experience that for many people it takes a lot to lose weight and keep it off. The combination of a low-insulin-index diet and fasting is the easiest way I know of to lose weight and keep it off. But you and I don't get to choose how much fasting it takes. That is an experimental matter. You have to do whatever it takes.

As with the monetary policy analogy I pursued in "Magic Bullets vs. Multifaceted Interventions for Economic Stimulus, Economic Development and Weight Loss," doing whatever it takes might seem extreme to onlookers. But it takes whatever it takes. And if done right, I think what it will take won't be all that painful to you, however surprised onlookers are that you can maintain it.

Self-discipline is necessary for losing weight and keeping it off; suffering is not. If you are suffering in steady-state, I'd like to hear about it to see if I can give some useful advice based on my own experience and the experience of those I know well.

By "suffering" I mean something quite specific: I mean what most people experience when they try calorie-restriction as their main strategy for weight-loss without introducing elements of either

- fasting

- low-insulin-index eating (or at least low-carb eating).

That type of suffering—familiar to so many who have tried raw, unsubtle calorie restriction as a primary strategy—is unnecessary.

Time-restricted eating, coupled with staying low on the insulin index in one's food choices,

- doesn't involve suffering

- is consistent with a lot of variety in food, and

- is consistent with eating heartily on social occasions,

but to anyone who gets you to speak frankly about your eating patterns the total amount of food you consume when following this strategy will look surprisingly low.

There is a limit to how efficient your metabolism can get, but at maximum metabolic efficiency, it doesn't take that much food to keep you going. As I have mentioned before, there is a silver lining to metabolic efficiency: cancer cells tend to be metabolically damaged, so operating on just the amount of food needed to keep you fully energetic when at maximum metabolic efficiency means there isn't a lot of extra nutrients around to keep metabolically inefficient cancer and precancer cells going. I have a set of posts on that:

- How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

- Why You Should Worry about Cancer Promotion by Diet as Much as You Worry about Cancer Initiation by Carcinogens

- Good News! Cancer Cells are Metabolically Handicapped

- How Sugar, Too Much Protein, Inflammation and Injury Could Drive Epigenetic Cellular Evolution Toward Cancer

Conclusion

I recognize that what works may be a path difficult for many people to follow. But I am reassured that there are many people out there who are much better at figuring out how to help keep people on track and motivated than I am. At this stage in human history, I believe what is most needed in fighting obesity is to get the facts about what works right. Helping people to use that knowledge depends on establishing the knowledge first.

By "what works" I mean not only being successful at losing weight and keeping it off, but also doing so with a minimum of suffering. As an economist, I would consider suffering a bad thing, even if suffering had no adverse effects on health whatsoever. But suffering also makes a weight loss program difficult to sustain, so suffering does have a bad effect on health. So minimizing suffering is crucial. The combination of fasting and a low-insulin-index diet does that.

Don't miss these other posts on diet and health and on fighting obesity:

- Stop Counting Calories; It's the Clock that Counts

- 4 Propositions on Weight Loss

- Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid

- Obesity Is Always and Everywhere an Insulin Phenomenon

- The Problem with Processed Food

- Which Is Worse for You: Sugar or Fat?

- Our Delusions about 'Healthy' Snacks—Nuts to That!

- My Giant Salad

- Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

- How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

- Why You Should Worry about Cancer Promotion by Diet as Much as You Worry about Cancer Initiation by Carcinogens

- Good News! Cancer Cells are Metabolically Handicapped

- How Sugar, Too Much Protein, Inflammation and Injury Could Drive Epigenetic Cellular Evolution Toward Cancer

- Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

- The Keto Food Pyramid

- Sugar as a Slow Poison

- How Sugar Makes People Hangry

- Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet

- Hints for Healthy Eating from the Nurse's Health Study

- The Case Against Sugar: Stephan Guyenet vs. Gary Taubes

- The Case Against the Case Against Sugar: Seth Yoder vs. Gary Taubes

- Gary Taubes Makes His Case to Nick Gillespie: How Big Sugar and a Misguided Government Wrecked the American Diet

- Against Sugar: The Messenger and the Message

- A Conversation with David Brazel on Obesity Research

- Magic Bullets vs. Multifaceted Interventions for Economic Stimulus, Economic Development and Weight Loss

- Mass In/Mass Out: A Satire of Calories In/Calories Out

- Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

- Carola Binder—Why You Should Get More Vitamin D: The Recommended Daily Allowance for Vitamin D Was Underestimated Due to Statistical Illiteracy

- Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

- Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

- Diseases of Civilization

- Katherine Ellen Foley—Candy Bar Lows: Scientists Just Found Another Worrying Link Between Sugar and Depression

- Ken Rogoff Against Sugar and Processed Food

- Kearns, Schmidt and Glantz—Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents

- Eating on the Road

- Intense Dark Chocolate: A Review

- In Praise of Avocados

- Salt Is Not the Nutritional Evil It Is Made Out to Be

- Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

- Whole Milk Is Healthy; Skim Milk Less So

- Is Milk OK?

- How the Calories In/Calories Out Theory Obscures the Endogeneity of Calories In and Out to Subjective Hunger and Energy

- Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

- 'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

- Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

- Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities

- On Fighting Obesity

- The Heavy Non-Health Consequences of Heaviness

- Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

- Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

- Podcast: Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation

Also see the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see my post "A Barycentric Autobiography."