Eleanor Singer →

I am sad that my University of Michigan Survey Research Center colleague Eleanor Singer died on June 3.

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

I am sad that my University of Michigan Survey Research Center colleague Eleanor Singer died on June 3.

Link to the Powerpoint file for all the slides in this post. For this post only, I hereby grant blanket permission for reproduction and use of material in this post and the Powerpoint file linked above, provided that proper attribution to Miles Spencer Kimball and a link to this post are included in the reproduction. This is beyond the usual level of permission I give here for other material on this blog to which I hold copyright.

In my post "There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale" and my Storify stories "Is There Any Excuse for U-Shaped Average Cost Curves?" and "Up for Debate: There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale," I criticize U-shaped average cost curves as a staple of intermediate microeconomics classes. But what should be taught in place of U-shaped average cost curves? This post is my answer to that question: returns to scale and imperfect competition in market equilibrium.

In order to talk about the degree of returns to scale and the degree of imperfect competition, we need a measure of each. The following notation is helpful:

The Degree of Returns to Scale

The degree of returns to scale can be measured by the percent change in output for a 1% change in inputs. I use the Greek letter gamma for the degree of returns to scale:

when there is only a single input in the amount x. (Note that throughout this post I use the percent change concepts and notation from "The Logarithmic Harmony of Percent Changes and Growth Rates" and write as equalities approximations that are very close when changes are small.)

According to the awkward, but traditional terminology, a degree of returns to scale equal to one is "constant returns to scale." A degree of returns to scale greater than one is "increasing returns to scale." As for a degree of returns to scale less than one, make sure to read "There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale."

If more than one input is used to produce the firm's output, a convenient way to gauge the increase in inputs is to look at the change in total cost holding factor prices fixed. This gives an aggregate of all the different factors weighted by the initial factor prices. Notice that for the standard production technology notion of returns to scale it doesn't matter if factor prices are actually unchanging as the firm changes its level of output; holding factor prices fixed is simply a way to get an index for total factor quantities akin to the way real GDP is measured. Using the percent change in total cost with factor prices held fixed to gauge the percent change in inputs, the degree of returns to scale with multiple factors is:

Remember that this equation is about what happens when a firm changes the quantity of its output, always producing that output in a minimum cost way given those fixed factor prices. If factor prices or technology are changing, then this equation does not hold.

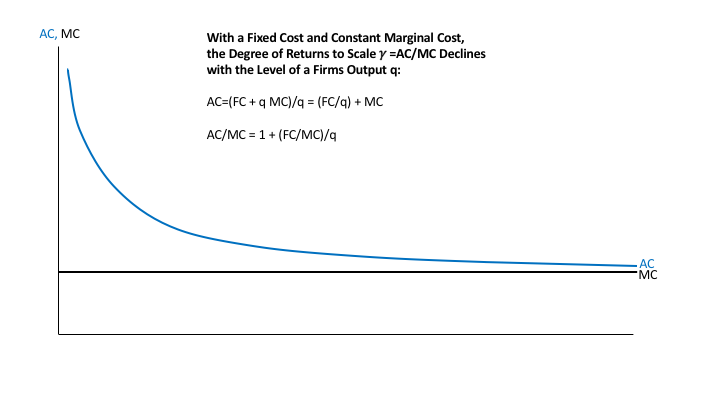

I argue that the degree of returns to scale will typically be declining in the quantity of output. I base this in part on the idea that a fixed cost coupled with a constant marginal cost is the base case we should start from as economists. Here is why the degree of returns to scale declines with the level of output when a firm has a fixed cost coupled with a constant marginal cost:

According to the derivation above, the degree of returns to scale gamma is equal to AC/MC. Thus, when a firm has a fixed cost coupled with a constant marginal cost for the product whose cost is depicted, the degree of returns to scale declines with the level of the output for that product. What is more, if marginal cost MC is constant, the degree of returns to scale gamma = AC/MC has the same shape as the average cost curve AC, though the vertical scale for the degree of returns to scale would have 1 in place of MC.

The Degree of Imperfect Competition

The degree of imperfect competition can be measured by how far above its marginal revenue a firm will want to set its price: the desired markup ratio p/MR. I use the Greek letter mu for the desired markup ratio. Since a firm tries to set its price so that marginal revenue equals marginal cost, this is also how far above its marginal cost a firm will want to set is price. This actual markup ratio p/MC can be different from the desired markup ratio p/MR over periods of time when the firm doesn't have full price flexibility, but in long-run equilibrium, the actual markup ratio P/MC should be equal to the desired markup ratio p/MR.

The desired markup ratio that measures the degree of imperfect competition is closely related to the price elasticity of demand a firm faces, but goes up when the price elasticity of demand the firm faces goes down. I use the Greek letter epsilon for the price elasticity of demand faced by a firm. The key identity can be derived as follows:

Here is a table giving the desired markup ratio for various values of the price elasticity of demand faced by a firm:

Price Elasticity of Demand Faced by a Firm epsilon Desired Markup Ratio mu

1 infinity

1.5 3

2 2

2.5 1.67

3 1.5

4 1.33

5 1.25

6 1.2

7 1.17

8 1.14

10 1.11

11 1.1

21 1.05

101 1.01

infinity 1

There are several noteworthy aspects about this table. First, if a firm has a marginal cost of zero, in long-run equilibrium it will seek out a price at which the price elasticity of demand it faces is equal to 1. The infinite markup ratio corresponds to a positive price divided by a zero marginal cost. I plan to talk about the market equilibrium for this case in a future post.

If a firm has any positive marginal cost, then in long-run equilibrium, regardless of what other firms do, it will keep raising its price until it reaches a price at which the price elasticity of demand it faces is greater than 1, unless it can get away with providing an infinitesimal quantity at an infinite price. (Being able to get away with providing an infinitesimal quantity at an infinite price is unlikely.) Therefore with a positive marginal cost, the desired markup ratio will be finite and greater than one.

A higher desired markup ratio corresponds a lower price elasticity of demand. And a higher desired markup ratio corresponds to more imperfect competition. The desired markup ratio is a very convenient way to measure the degree of imperfect competition.

Market Equilibrium

The graph at the top of this post illustrates market equilibrium. I return to that graph below. For the logic behind market equilibrium, let me quote from my paper "Next Generation Monetary Policy":

Given free entry and exit of monopolistically competitive firms, in steady state average cost (AC) should equal price (P): if P > AC, there should be entry, while if P < AC there should be exit, leading to P=AC in steady state. Price adjustment makes marginal cost equal to marginal revenue in steady state. Thus, with free entry, in steady state,

where by a useful identity γ is equal to the degree of returns to scale and μ is a bit of notation for the desired markup ratio P/MR. The desired markup ratio is equal in turn to the price elasticity of demand epsilon divided by epsilon minus one:

Remarkably, in long-run equilibrium, after both price adjustment and entry and exit, the degree of returns to scale must be equal to the degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup.

I am going to make four key simplifications to make it easier to understand market equilibrium. First, I will assume that the market equilibrium is symmetric so that each firm sells the same amount q. Second, I will assume, at least for the benchmark case that the elasticity of demand for the entire industry's output is zero. That is, customers are perfectly happy to shift from buying one firm's output to buying another firm's output at the elasticity epsilon if they can get a better deal, but they insist on a certain amount of the category of good provided by the industry. Using the letter Q for the total sales in the industry, that means

Q=nq

n=Q/q

q=Q/n

Third, I will assume that the price elasticity of demand a firm faces—and therefore its desired markup ratio—depends only on the number of firms in the industry. Fourth, I will assume that all fixed costs are flow fixed costs rather than being sunk. It is interesting to relax each of these assumptions, but it would be hard to understand those cases without first learning the simplified case I am presenting here. (The most difficult to relax is the symmetry assumption. Relaxing that assumption is least likely to meet the cost-benefit test in the tradeoff between tractability and realism.)

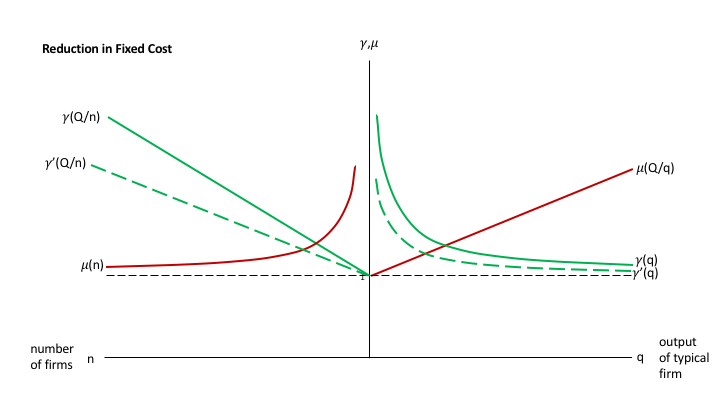

Let me reprise the graph at the top of this post to explain how it illustrates market equilibrium:

This graph is really two interlocking graphs. On the right, the degree of returns to scale and the degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup ratio are shown in relation to the output of a typical firm. On the left, the degree of returns to scale and the degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup ratio are shown in relation to the number n of firms in the industry.

The degree of returns to scale declines with output as explained above. For given total sales in the industry Q, that means that the degree of returns to scale increases with the number of firms in the industry.

The degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup ratio decreases with the number n of firms in the industry. For given total sales in the industry Q, that means that the degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup ratio increases with a typical firm's output q.

The assumption that—other things equal—the degree of imperfect competition declines with the number of firms is intuitive—and I believe correct in the real world. But I should note that there is a very popular model—the Dixit-Stiglitz model—that is popular in important measure because it makes the degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup ratio constant, regardless of how many or few firms there are. The Salop model gives a degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup ratio that declines with the number of firms. But the Salop model is less convenient technically than the Dixit-Stiglitz model. Innovation could be valuable here. A model that had an attractive story, was technically convenient and had a desired markup ratio declining in the number of firms should be able to attract a subsantial number of users. In any case, I stand by the claim that to model the real world, one should have the desired markup ratio declining in the number of firms in the industry.

The intersection on the right shows the long-run equilibrium output of a typical firm in this industry. The intersection on the left shows the long-run equilibrium number of firms in the industry.

When mu > gamma. Though this could be questioned, think of entry and exit happening at a slower pace than price adjustment. (I discuss the relationship between some other adjustment speeds in "The Neomonetarist Perspective.") Once prices have adjusted, MC = MR. So if the degree of imperfect competition mu = p/MR is greater than the degree of returns to scale gamma = AC/MC it means that p > AC and there will be entry. As n rises, AC and p will come closer together until they are equal at the intersection on the left side of the graph.

When mu < gamma. On the other hand, If the degree of imperfect competition mu = p/MR is less than the degree of returns to scale gamma = AC/MC, it means that p < AC and there will be exit. As n falls, AC and p will come closer together until they are equal at the intersection on the left side of the graph.

To summarize:

If mu > gamma, firms enter.

If gamma > mu, firms exit.

In either case, as n adjusts, the quantity of a typical firm's output also changes.

Comparative Statics

Let's consider four thought experiments. First, consider an increase in total sales Q by the industry. This shifts out both curves that are written in terms of Q:

The prediction is that both the number of firms and the output of a typical firm will increase, while both the degree of returns to scale and the degree of imperfect competition will fall. Because the curve showing the desired markup as a function of the number of firms does not shift, the reduction in the the desired markup only occurs as new firms actually enter. The degree of returns to scale overshoots: it drops most right after the increase in total industry sales Q, then gradually rises again as new firms enter and the quantity produced by each firm declines.

Second, consider reduction in the (flow) fixed cost. This cases the returns to scale (gamma) curves on both sides to shift downward:

The prediction is that the number of firms will increase, while the size of a typical firm decreases, and that both the degree of returns to scale and the degree of imperfect competition will fall. Because the desired markup curves does not shift, the desired markup only falls as new firms actually enter, which is likely to be gradual. As in the first experiment, the degree of returns to scale overshoots in the sense of dropping most at first.

With the marginal cost unchanged, the fall in the desired markup ratio leads to a reduction in price. That would expand the size of the industry if the elasticity of demand for the industry product category as a whole were nonzero. That in turn would require the results of the first experiment in order to analyze.

Third, consider a reduction in marginal cost. This causes the returns to scale curves on both sides to shift up, since returns to scale equals AC/MC, and because it includes average fixed cost, AC does not fall as much as MC. However, the effect of MC on AC means that the gamma = AC/MC curves do not rise vertically by as large a percentage as MC falls.

The prediction is that the output of a typical firm will rise, while the number of firms will decline. The degree of returns to scale and degree of imperfect competition rise in the long run. But note that this is because of improved performance of the industry in reducing costs. The equilibrium desired markup ratio rises less than the degree of returns to scale curve, which in turn rises by a smaller percentage than MC falls. The price will be lowest before firms have had a chance to exit—indeed it will initially fall by the full percentage of the decline in MC—but will remain lower in the new long-run equilibrium than in the old long-run equilibrium.

Again, if the elasticity of demand for industry output as a whole is nonzero, the decline in price would lead Q to increase (more at first, somewhat less later on), so the results of the first experiment would be necessary to fully analyze what would happen.

Fourth, consider an increase in the price elasticity of demand for any given number of firms. This might be described as the market becoming "more price-competitive." Both desired markup curves fall:

The prediction is that in the long run the number of firms falls, while the output of the typical firm rises. This might be called a "shakeout" of the industry. Because the industry has become more price-competitive, the number of firms falls. Someone coming from the ancient "Structure-Conduct-Performance" paradigm for Industrial Organization might be confused because the concentration of the industry goes up, yet the performance of the industry improves: the degree of imperfect competition as measured by the desired markup falls, as does the degree of returns to scale in long-run equilibrium.

With MC unchanged, the desired markup and therefore the price falls most right at first, before firms have had a chance to exit. Then the price comes up somewhat, but remains lower than in the initial long-run equilibrium. If the price elasticity of demand for the entire industry's output is nonzero, then Q will increase, especially at first, which will complicate the analysis in ways that the first experiment can help navigate.

Conclusion

In my view, the foregoing analysis is

more on-target than U-shaped average cost curves in relation to the real world

more interesting than U-shaped average cost curves

no harder than U-shaped average cost curves, if one sticks to the simplifications I made. What I have laid out above is difficult, but U-shaped average cost curves are also difficult.

Therefore, it seems better to me to teach returns to scale and imperfect competition in market equilibrium than it is to teach U-shaped average cost curves. In any case, there are always tradeoffs. When it is impossible to teach both, what I have laid out in this post is the opportunity cost for teaching U-shaped average cost curves. I hope you will agree it represents a high opportunity cost, indeed.

Both of these are ungated. Ken Rogoff's abstract gives a good sense of the review and response:

Jeffrey Hummel provides an extremely thoughtful and detailed review, which is welcome, even if there are a number of places where I don’t quite agree with his interpretations, emphasis, and analysis. For example, the notion that central banks already can use helicopter money to solve the zero bound, and that there is little need for negative interest-rate policy in the next deep financial crisis, is dubious. It is also important to stress that the book is about the whole world and not just the United States; there are good reasons why many other advanced economies may find it attractive to move away from the status quo on cash much more quickly than the United States will. Importantly, deciding how to move to a less-cash society should be looked at as a question of calibration, not an all-or-nothing proposition, and not something that needs to be done quickly.

"Justice" in Chinese Characters: "seigi." Image source.

The mere existence of something called a "justice system" does not entitle it to respect. It earns respect by satisfying three conditions, corresponding to three points in my discussion in "John Locke: When the Police and Courts Can't or Won't Take Care of Things, People Have the Right to Take the Law Into Their Own Hands":

To some extent, imperfection on either condition 2 or 3 can be compensated for by doing well on the other of these two conditions. For example, assuming superiority over having people judge their own cases (not hard), either of

would entitle a "justice system" to respect as a justice system without shudder quotes.

Note that sheer power is a big factor in meeting or exceeding condition 3. Thus, as a matter of realpolitik, the nominally designated "justice system" often deserves respect because of its great superiority in execution judgments, as long as its judgments are reasonably good.

Delivering on judgments has two key components:

In the 1st half of section 20 of his 2d Treatise on Government: “On Civil Government”, John Locke emphasizes the pretrial aspect of delivering justice, presumably because of its greater difficulty:

But when the actual force is over, the state of war ceases between those that are in society, and are equally on both sides subjected to the fair determination of the law; because then there lies open the remedy of appeal for the past injury, and to prevent future harm: but where no such appeal is, as in the state of nature, for want of positive laws, and judges with authority to appeal to, the state of war once begun, continues, with a right to the innocent party to destroy the other whenever he can, until the aggressor offers peace, and desires reconciliation on such terms as may repair any wrongs he has already done, and secure the innocent for the future;

In the 2d half of section 20, John Locke emphasizes the importance of accuracy and unbiasedness:

nay, where an appeal to the law, and constituted judges, lies open, but the remedy is denied by a manifest perverting of justice, and a bare-faced wresting of the laws to protect or indemnify the violence or injuries of some men, or party of men, there it is hard to imagine any thing but a state of war: for where ever violence is used, and injury done, though by hands appointed to administer justice, it is still violence and injury, however coloured with the name, pretences, or forms of law, the end whereof being to protect and redress the innocent, by an unbiassed application of it, to all who are under it; where ever that is not bona fide done, war is made upon the sufferers, who having no appeal on earth to right them, they are left to the only remedy in such cases, an appeal to heaven.

What is obvious is that accurately delivering justice is a good thing. The nuance here is that, just as a company that does shoddy work not only does a bad thing but also may lose customers, a "justice system" that does shoddy work not only does a bad thing but also may lose respect. A "justice system" that loses people's respect is often spoken of as having lost its "legitimacy." Legitimacy in this sense is the natural law that judges the civil law in action.

The August 2013 National Geographic article "Sugar Love (A not so sweet story)" by Rich Cohen collects some powerful quotations from experts describing sugar as a slow poison. It also gives some of the slavery-flavored history of sugar. (If Eric Eustace Williams first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago is right, slavery beginning with the triangle trade was a key source of racism as well. He said "Slavery was not born of racism; rather, racism was the consequence of slavery.")

Here are some key passages from pages 87 and 96 about sugar (the pages in between show beautiful pictures of sugary foods by photographer Robert Clark):

"It seems like every time I study an illness and trace a path to the first cause, I find my way back to sugar."

Richard Johnson, a nephrologist at the University of Colorado Denver, was talking to me in his office in Aurora, Colorado..."Why is it that one-third of adults [worldwide] have high blood pressure, when in 1900 only 5 percent had high blood pressure?" he asked. "Why did 153 million people have diabetes in 1980, and now we're up to 347 million? Why are more and more Americans obese? Sugar, we believe, is one of the culprits, if not the major culprit."

... Haven Emerson at Columbia University pointed out that a remarkable increase in deaths from diabetes between 1900 and 1920 corresponded with an increase in sugar consumption. And in the 1960s the British nutrition expert John Yudkin conducted a series of experiments in animals and people showing that high amounts of sugar in the diet led to high levels of fat and insulin in the blood—risk factors for heart disease and diabetes. But Yudkin's message was drowned out by a chorus of other scientists blaming the rising rates of obesity and heart disease instead on cholesterol caused by too much saturated fat in the diet.

As a result, fat makes up a smaller portion of the American diet than it did 20 years ago. Yet the portion of America that is obese has only grown larger. The primary reason, says Johnson, along with other experts, is sugar, and in particular, fructose. Sucrose, or table sugar, is composed of equal amounts of glucose and fructose, the latter being the kind of sugar you find naturally in fruit. ... (High-fructose corn syrup, or HFCS, is also a mix of fructose and glucose—about 55 percent and 45 percent in soft drinks. The impact on health of sucrose and HFCS appears to be similar.)

... Over time, blood pressure goes up, and tissues become progressively more resistant to insulin. The pancreas responds by pouring out more insulin, trying to keep things in check. Eventually a condition called metabolic syndrome kicks in, characterized by obesity, especially around the waist; high blood pressure; and other metabolic changes that, if not checked, can lead to type 2 diabetes, with a heightened danger of heart attack thrown in for good measure. As much as a third of the American adult population could meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome set by the National Institutes of Health. ...

"It has nothing to do with its calories," says endocrinologist Robert Lustig of the University of California, San Francisco. "Sugar is a poison by itself when consumed at high doses."

Books referred to by the article:

Related Story: How the Calories In/Calories Out Theory Obscures the Endogeneity of Calories In and Out to Subjective Hunger and Energy

There is no such thing as decreasing returns to scale. Everything people are tempted to call decreasing returns to scale has a more accurate name. The reason there is no such thing as decreasing returns to scale was explained well by Tjalling Koopmans in his 1957 book Three Essays on the State of Economic Science. The argument is the replication argument: if all factors are duplicated, then an identical copy of the production process can be set up and output will be doubled. It might be possible to do better than simply duplicating the original production process, but there is no reason to do worse. In any case, doing worse is better described as stupidity, using an inappropriate organizational structure, or X-inefficiency rather than as decreasing returns to scale.

The replication argument is extremely valuable as a guide to thinking about production since it often identifies a factor of production that might otherwise be ignored, such as land, managerial time, or entrepreneurial oversight. Thinking through what difficulties there might be in practice in duplicating a production process at the same efficiency helps to identify key factors of production if those factors of production were not already obvious.

The nonexistence of decreasing returns to scale implies that the U-shaped average cost curve still taught routinely to most economics students, with its decreasing returns to scale region, is not what it seems. I got into a debate about this on Twitter, which I storified in "Is There Any Excuse for U-Shaped Average Cost Curves?" A U-shaped average cost curve might be justifiable as a cost-curve per top-level manager, or perhaps as a cost-curve per entrepreneur. But including all inputs, including both managerial and entrepreneurial time and effort, production must still be at least constant returns to scale if not increasing returns to scale.

In addition to crowding out the clarity of the replication argument, the emphasis in many economics classes on the so-called U-shaped average cost curve makes it harder for students to get the idea of increasing returns to scale clearly in their minds. Much better would be to use something like the graph below to teach students about increasing returns to scale:

Given the replication argument, there is no scale of operation that is beyond efficient scale. There may be ample reason to make different plants or divisions quasi-independent so they do not interfere with one another's operations. But that is not an argument against scale per se. There may even be reason to set up incentives so that different divisions are almost like separate firms, headed by someone in an entrepreneurlike position. But that still is not, properly speaking, an example of diseconomies of scale.

Even those who disagree with me on some of the points above should agree that a debate on these issues, beginning with the challenges I have made above, would be good for student understanding of production.

Besides pedagogical inertia—enforced to some extent by textbook publishers—I am not quite sure what motivates the devotion in so many economics curricula to U-shaped average cost curves. Let me make one guess: there is a desire to explain why firms are the size they are rather than larger or smaller. To my mind, such an explanation should proceed in one of three ways, appropriate to three different situations.

If returns to scale are constant, then everything can be done on a per manager or per entrepreneur basis. This might still use diagrams similar to U-shaped average cost curves, but would be quite explicit about the fact that one factor was held constant, so that the upward-sloping part of the U-shaped average cost curve does not represent true decreasing returns to scale, but rather decreasing returns to scale in all other factors when managerial or entrepreneurial input is held constant.

If returns to scale are increasing, the size of the firm can be made determinate by having a downward-sloping demand curve. (I discuss in some detail the relationship between increasing returns and imperfect competition in "Next Generation Monetary Policy" and hope to return to discussing this relationship in a future blog post.)

If the firm is large enough relative to its suppliers and labor force that increasing its scale noticeably increases factor prices, that may limit a firm's scale. This is not properly decreasing returns to scale simply because returns to scale is defined over quantities, and so when translated into cost terms is effectively defined for given factor prices. In any case, to my mind, the analytical distinction between the production function and interaction with factor markets is an analytical distinction worth highlighting.

What I am most confident of is that microeconomic teaching of production as we know it, with the U-shaped average cost curve in center stage, is suboptimal. Let's change it. The way I think about production may not be the best way, but the way it is now taught is definitely not the best way.

Don't miss the followup post: "Returns to Scale and Imperfect Competition in Market Equilibrium."

Update: In addition to the comments below (visible when you go to the post itself or click on the post title), this post has sparked a vigorous debate on Twitter, which I organized in this Storify story: "Up for Debate: There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale." In these storified tweets, I answer many questions you may have as well. I will try to keep that story updated. And here is a link to the debate on my Facebook page.

Here are some of the most instructive comments, and some of my replies:

Chris Kimball: The replication argument is so obviously correct that every "diminishing return to scale" presentation is implicitly or explicitly holding one or more factor constant. That much seems near tautological. As a result, this strikes me as a pedagogy discussion. What's the preferred way to tease out these concepts? Given the fact that in the real world there really are constraints both internal and external, factors really are limited, and perfect replication is a thought experiment more than an observation.

Miles: Absolutely. We are thinking along very much the same lines.

mike: But isn't franchising an example of where people realize that to get a local manager that cares at 2,000 locations, its better to seperate ownership interests. You talk about territory distribution etc, but I would argue that is an example of needing that remedy to overcoming decreasing returns to scale.

Miles: I love your example of a franchising system. This is exactly what I mean by having a firm organization that allows one to replication owner/entrepreneurs. The franchisees become one more input in the system from the point of view of headquarters. I wish I had thought of this example!

Patrick Neal Russell Julius: My favored way of explaining this is describing the last factor of production as "planets". If you were to copy the Earth in its entirety, in every detail, it strains all credulity to imagine that you could do any less than double total output. So there must be SOME factor of production that would allow you to have at least constant returns to scale—though if it is indeed planets, obtaining more of that factor might be quite prohibitive even in what we normally call the "long run".

Chris Makler: ... workers being homogenous fails ... If your production function only involves computer servers, fine; double the servers, double the traffic (or even more, but you get the point). But once you start hiring humans it's completely different. By definition if you have 10 slots to fill and 30 applicants, you fill the slots with the 10 people who are the best match. If you have 20 slots to fill, you go down the list. So DRS follows directly from some form of match-specific productivity.

Miles: This is very interesting. After adjusting for input quality, the amount of labor doesn't really double when the firm goes from 10 employees to 20. But "quality" of a worker may be firm specific, and so not visible in other data that isn't specific to the firm.

In the Twitter debate storified in "Up for Debate: There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale," the most interesting discussions to me were about communications within the firm and the production of software. Here is my summary of the issues and what I think is their resolution:

Communication Within a Firm: If every employee is encouraged to talk to every other employee, then the number of communication lines goes up with the square of the number of employees. A vast volume of communication could start to drag down production. The answer I give is that as an organization grows it needs siloing: groups with a lot of communication within the group, but limited communication between groups. Siloing is usually only mentioned in order to criticize it, but siloing has the huge benefit of helping to keep people from being overwhelmed with emails, for example. The trick is to get interaction between groups where that interaction is likely to be helpful, and avoid interaction between groups where that communication is a cost with little benefit.

The Writing of Software and Books, Recording of Songs and Shows, etc.: Sam Vega asks "Doesn't throwing more programmers at a software project qualify as "decreasing returns of scale"?" There are two perspectives one can take here: thinking about copies of the software, book, song, shows, etc. (whether physical or digital copies) and thinking about different software programs, texts, songs, shows etc.

From the perspective of copies of the software, book, song, show, etc., the writing and recording is a fixed cost. Throwing more programmers at writing the software to try to do things faster raises the fixed costs and increases the returns to scale for the copies.

From the perspective of distinct software programs, books, songs, shows etc., the key point is that the replication argument only applies to the production of identical items. Leaving aside copies, you only need one of the code for each type of software. If you are only going to produce one, then returns to scale don't apply. On the other hand, if you are willing to consider an array of different computer games, say, as distinct but on par (a symmetry assumption), then it should be possible to create 10 distinct games in the same amount of time if one has ten times the input.

Another way to put it is that cutting the time it takes to produce something in half is not at all the same as producing twice as much of something in the same amount of time.

Don’t miss the follow-up post “Returns to Scale and Imperfect Competition in Market Equilibrium.”

This was a fascinating conference. The link above takes you to separate links for each presentation in the conference. My coauthor Dan Benjamin is heavily involved in genoeconomics as well as well-being research. I hope to get more involved in genoeconomics myself, as I mentioned in "Restoring American Growth: The Video."

A key aspect of higher religion—that holds for nonsupernaturalist religion as well as supernaturalist religion—is serious attention to choosing the governing goals for human action. Economists spend a lot of time studying how to make choices in order to best achieve their goals given the limitations of the situations they are in. But (perhaps because of the kind of modeling difficulties I discuss in "Cognitive Economics") economists spend much less time studying metachoice: the choice of the goals themselves. This is particularly true for the choice—based in part on goals that then might be fully superseded—of those goals that become an individual's ultimate goals.

Someone who successfully proposes goals for others that they had never before conceived of can be thought of as a kind of prophet—whether a supernaturalist prophet or nonsupernaturalist prophet. The possibility of a future prophet identifying a new goal that many people would gladly take on makes it impossible to circumscribe the universe of all attractive human objectives. People want more than the things money can buy. They want more than happiness and life satisfaction. And they potentially want many things that they have never even dreamed of.

In addition to prophets, who successfully propose goals for others, there are coaches who help people choose objectives for themselves. Such coaches might be friends, teachers, clergy, psychotherapists, leaders of human growth workshops, or people who call themselves "life coaches." Metachoice is so important that most people should seek out some coach to help them think through what they want their goals to be. Those who can't find such a coach in someone else competent to do that job need to coach themselves on a careful choice of their own objective function; but that is more difficult.

In the mid-1990's I attended a series of excellent personal growth workshops by Landmark Education. In the "Advanced Communication Course" I was encouraged to identify my personal objectives and create a symbolic reminder of them. The star whose two sides are shown at the top of this post is the result. One side of the star—which I show first—gives headings for the objectives that are designed to spark curiosity. The other side gives the objectives themselves. In the Landmark Education courses, each of these objectives is typically preceded by the stem "I am the possibility of ..." as an expression of personal identification with that goal. The relationship between the heading on one side and the objective on the other side is clear for most. For those without the Mormon upbringing I had, the meaning of "Zion" might be unclear. I explain it this way in "Teleotheism and the Purpose of Life":

Zion, the ideal society—that we and our descendants can build.

The expression of my own personal objective function that I created in that Landmark course has had an important effect on my life. I want to illustrate that in relation to my career, this blog, and my personal life.

The reason I am writing about how my career, this blog, and my personal life have been shaped by my personal objective function today is that today is the 5th anniversary for supplysideliberal.com: my first post, "What is a Supply-Side Liberal," appeared on May 28, 2012. I have had an anniversary post every year since:

Now, on to how my objective function plays out in my career, this blog and my personal life.

Profound Relationship

My most profound relationship is my marriage. I have two Valentine's Day posts about marriage:

My relationships with my children are different, but profound in their own way. After my mother died in Fall of 2012, I made a point of visiting my Dad often, fearing he would also die soon, and was gratified to have four years to deepen that relationship. As a bonus, since the rest of my brothers and sisters lived close to my Dad, my visits to my Dad also provided occasions for my brothers and sisters and I to get together and deepen those relationships.

I have a set of wonderful relationships that are quite intentional. Men often need more friends than they would have without intentionally setting out to have friends. In Ann Arbor, I belonged to a group of Mormon and formerly Mormon men that met every two weeks in its heyday and sporadically in more recent years to the present day. Given the closeness of the group, they were OK with my decision to leave Mormonism in 2000. I also joined a Men's Circle established by the Men's Movement within my Unitarian-Universalist Congregation in Ann Arbor that meets every two weeks. The meetings of our Unitarian-Universalist Men's Circle are consciously designed to encourage self-disclosure: sharing true stories and ruminations about our lives. My Mormon Men's Group and Unitarian-Universalist Men's Circle fostered some of the closest relationships I have outside of my own family. In particular, my friend Kim Leavitt is the one other person who belongs to both groups and my friend Arland Thornton is the one who now holds my Mormon Men's Group together.

Professionally, my most profound relationships are those with my coauthors and others I am working with. One sign of a profound relationship is when working through strong disagreements makes the relationship stronger, rather than disagreements causing the relationship to disintegrate. That describes the relationships I have had with others in what we have called the "Well-Being Measurement Initiative": Dan Benjamin, Ori Heffetz and Kristen Cooper. In the work of the Well-Being Measurement Initative, which absorbs the bulk of my research time these days, I also treasure the relationships I have had with our amazing research assistants (Samantha Cunningham, Pierre-Luc Vautrey, Becky Royer, Robbie Strom, and Tuan Nguyen), then-graduate-student coauthors (Alex Rees-Jones, Nichole Szembrot, Derek Lougee and Jakina Debnam) and other more senior coauthors (Marc Fleurbaey and Collin Raymond), but those relationships have not had occasion to weather any serious disagreements.

My blog has led to some surprisingly deep relationships. Here are some examples:

Human Connection and Justice and Welfare

When I write of "making the world a better place"—or more extravagantly of "saving the world"—I mean advancing human connection and justice and welfare. These three are very closely related. In particular, now that humanity as a whole has gained some power over nature, the greatest evils in the world come from a failure of "human connection," as groups of other human beings are seen as something less than fully human. I explore this phenomenon in "Us and Them," "The Hunger Games" Is Hardly Our Future--It's Already Here," "'Keep the Riffraff Out!'" Nationalists vs. Cosmopolitans: Social Scientists Need to Learn from Their Brexit Blunder," and "The Aluminum Rule."

Professionally, my two biggest efforts to make the world a better place right now are my work on negative interest rate policy and my work with the Well-Being Measurement Initiative to build national well-being indices that can help identify what people want and what policies are most successful in helping them get there. On my blog I also advocate many other ways to make the world a better place. To see one of my favorites, take a look at "How and Why to Expand the Nonprofit Sector as a Partial Alternative to Government: A Reader’s Guide." (I hope to give a better rundown of policies I have advocated in a bibliographic post sometime this Summer.)

I have felt some psychological pull toward more direct government service, but at this point in my life any significant direct government service seems increasingly unlikely.

For advancing human connection and justice and welfare, I consider religion and philosophy as well as science and public policy. It has been very interesting blogging about religion every other Sunday and blogging my way through John Stuart Mill's On Liberty and John Locke's Second Treatise on the other Sundays.

Overall, there are three moral principles that keep coming up as I think about making the world a better place:

On the third point, I find myself especially distressed when someone in an academic position cares more about advancing their career than they do about the truth.

In my personal life, my efforts to advance human connection and justice and welfare are random but real. I don't notice everything around myself, but when I do notice an injustice, I want to do something about it. I don't mean it is all to the good, but I think the fact that I don't notice everything around myself keeps me from burning out.

All People Being Empowered by Math and Other Tools of Understanding

Professionally, a big part of my teaching (for undergraduates as well as graduate students) is helping students to understand math. I hope I can both make potentially hard things easy and also instill some enthusiasm for math and related tools of understanding such as logic and graphs. I hope some of my papers accomplish the same job of making what could be difficult math a little easier.

Without consciously setting out to make math a theme of my blog, it has become one. "There’s One Key Difference Between Kids Who Excel at Math and Those Who Don’t," which I wrote with Noah is by far my most read piece, and my follow-up pieces also did well (though at least an order of magnitude less in readerships): "How to Turn Every Child into a 'Math Person'" and "The Coming Transformation of Education: Degrees Won’t Matter Anymore, Skills Will." I also have many minor posts on this theme; one recent post in this category is "You, Too, Are a Math Person; When Race Comes Into the Picture, That Has to Be Reiterated."

In my personal life, I hope I transmit a bit of my love for math through my dabbling with number theory. I have had some success in inveigling my wife Gail in memorizing hotel room numbers by factoring them. I make Archimedean solids and other geometrical shapes with Magnetix

and try to show how each number is interesting in the birthday signs I draw for my children, such as this one for my daughter Diana:

Adventure into the Unknown

Intellectually, I am a contrarian, which does a lot to bring me into new territory. I try hard to think up new angles on questions in front of me and to combine ideas from different sources. I love to dive into fields and subfields I haven't done research on before. (You can see this in the REPEC ranking analysis I have a link for here: one of the dimensions I rank highest among economists in the world is in "breadth of citations across fields.")

On my blog, I delight in tackling new topics. I arranged my bibliography of "key posts" to show the variety of subjects I have written on.

Attending seminars and reading tweets continually introduces me to new ideas.

My travels to talk about negative interest rate policy have had the fortunate side effect of letting me explore many places in the world (1, 2). Those travels have also given me a chance to see great works of art in some of the greatest museums in the world. I hope a little bit of the visual sensibility from that time in art museums comes across in this blog.

In my personal life, I manage to do "adventures into the unknown" without being particularly daring. I like to do urban hiking to explore nooks and crannies of cities I am visiting or of my home city (which is now Superior, Colorado). I often try one of the more exotic dishes on a restaurant menu. And I read science fiction.

Lately, I have realized that a willingness to "adventure into the unknown" is important in preserving a commitment to truth. The truth is not always what one thought at first. So a willingness to go someplace new is a prerequisite in many cases for arriving at the truth.

A willingness to "adventure into the unknown" is also crucial for arriving at "profound relationship." One of the best ideas from the Landmark Communications courses was the idea that one should listen to those close to you as if you don't know what they are going to say next. The opposite of acting as if you always know what someone is going to say next is a surefire way to wear away any understanding you have of them.

Fun

I started out my life as quite a serious kid. So having fun is something I have needed to work on. But now, I have a lot of fun. In my professional life, I get to spend a lot of time talking to people. In all that talk, there is both a social element and a delicious competitive element of arguing one's points. Much the same is true of my blog, and Twitter and Facebook and my writing for Quartz, which I see as extensions of my blog. Often, when I sound very confident of what I am saying, what I am really thinking is "There is no way for me to be wrong without it being interesting." And that thought is almost always borne out: either I get the joy of being right, or I get the joy of seeing things from a new angle I hadn't thought of before.

In my personal life, fun comes in more varieties. I love the beauty of the landscape here in Colorado. I love learning new languages (something that contributed to my getting a Linguistics MA before I got an Economics PhD). I love vocal music, and often combine it with my love of foreign languages by listening to vocal music with non-English lyrics. I love reading both fiction and non-fiction. I love the great dramatic form of our age: TV. I love having friends and family come to visit.

I am not sure I understand how to make things fun for other people. I remember once at a men's retreat all the men going around the circle and telling a little about their hobbies. The variety was astounding. People are truly different in the leisure-time activities they love. I know many of my tastes are minority tastes. I seldom fall into the trap of pretending to like something I don't really like in order to appear more cultured or cool, though I do try to stretch to get an angle to understand why other people like something. It is a rare occurrence but fun for me when I run into someone who happens to share my tastes in some leisure-time pursuit.

Managing for Completion and Fulfillment-->All People Being Joined Together in Discovery and Wonder

The overall summary of all the objectives above is in the center of the star: "all people being joined together in discovery and wonder." After two decades or so since I took the Landmark Education courses, I still respond emotionally to that phrase. But the path to "all people being joined together in discovery and wonder" runs through "managing for completion and fulfillment." There are tasks that must be done, one by one, in order to get where I want us all to get to.

Professionally, teaching the classes I am scheduled to teach, keeping promises (explicit and implicit) to caouthors, and the deadlines imposed by conferences and journals often provide plenty of structure to propel things forward. Other times, self-discipline must be applied to get key things done. Overall, I feel if I complete all of the research projects I have already begun, plus their obvious spinoffs, I will have had a wonderful career.

On my blog, the rules and structures I have made up for myself have helped greatly in creating a set of blog posts I am very proud of. Trying to balance my other time demands with a determination that my blog continues to become richer and richer in its content, I have settled on the target of two substantial posts during the five weekdays (usually on Tuesday and Thursday) and a post on religion or philosophy on Sunday. It has turned out to be very easy to have a good link for the other days, including frequent links to Twitter debates that I have organized on Storify. (I would like to do many more Quartz columns than I have been doing lately. In addition to my own time constraints, current events seem to be running the editors I work with ragged on other fronts.)

In my personal life, trying to be a good husband, father, friend and family member provides most of the structure I need to do good things on a regular basis.

The back and forth between grand objectives and the determination to complete the day-to-day tasks needed to achieve those goals often seems counterintuitive and strange. But grand objectives without accomplishment of the crucial daily tasks along the way won't get anyone anywhere. And hard work without grand objectives is likely to get one a long way in the wrong direction. So that counterintuitive and strange back and forth between grand objectives and the determination to complete daily tasks is the only way to have much hope of saving the world—or even of making one's own corner of it a little better.

Related Posts:

I had some excellent comments on this article on my Facebook page. Here is the link.

I like Travis Bradberry's 10 ways to appear smarter than you are better after I arrange them into two lists: laudable and gimmicky. Here is my arrangement:

Laudable, in order from least to most laudable:

Gimmicky, in order from least to most gimmicky:

On the third laudable way to look smarter, "believe in yourself," I say this in "Calculus is Hard. Women Are More Likely to Think That Means They’re Not Smart Enough for Science, Technology, Engineering and Math":

In addition to discouragement, low confidence in oneself also causes other people to underestimate one’s skills. It is quite difficulty to know how skilled someone is, but typically quite easy to tell how skilled they think themselves to be. So people use a job candidate’s opinion of herself or himself as a shortcut for judging her or his skills.

For those who need to come across as more confident I highly recommend the weekend personal growth workshops conducted by Landmark Education Corporation, beginning with the Landmark Forum. In my view, almost everyone entering the dissertation writing and then job-hunting phases of getting a PhD in economics should do the Landmark Forum because of how much it will help the psychology of being able to focus on dissertation research and then the psychology of self-presentation for getting a job. I am sure that the same advice would apply to students in many other fields, at many stages of education.

My biggest disagreement with Travis is not my discomfort with gimmicky ways to appear smarter. It is with his conclusion

Intelligence (IQ) is fixed at an early age. You might not be able to change your IQ, but you can definitely alter the way people perceive you.

Au contraire: your intelligence is not fixed at all. It is possible to become much smarter by serious, well-focused effort. If you don't believe that, read these three columns on education:

What is said there about math also applies to many other mental skills.

I have had it verified by those in a position to know that among many economists in the city of Minneapolis, there is a view that can be summarized as

General equilibrium good, partial equilibrium bad.

I would like to contest the second half of this view, and qualify the first half. Here, when I speak of general equilibrium, I am thinking of a typical dynamic, stochastic general equilibrium model. When I speak of partial equilibrium, I am including models of a single agent's decision problem, such as the model of household decision-making that leads to the empirical consumption Euler equation. In both cases, I am thinking of models being taken to the data as opposed to models that are pure theory.

Why Partial Equilibrium Has an Advantage over General Equilibrium Models for Empirical Analysis

The basic problem with a general equilibrium model is that if any part of the model is misspecified, then inference (formal or informal) about the relationship between any other part of the model and the data is likely to be messed up. If that is not true, then the general equilibrium model is equivalent, or nearly equivalent to a partial equilibrium model, putting that partial equilibrium model and the general equilibrium model on an equal footing. (If a general equilibrium model is equivalent to a partial equilibrium model, then the general equilibrium aspect of the general equilibrium model is just window dressing.)

By contrast, a partial equilibrium model—say one that makes predictions conditional on observed prices—can be robust to ignorance about big chunks of the economy. For example, given key assumptions about the household (rational expectations, maximization of a utility function of a given functional form, absence of preference shocks, no liquidity constraints, etc.) the consumption Euler equation should hold regardless of how the production side of the economy is organized.

That statement about the robustness of the consumption Euler equation to ignorance about big chunks of the economy holds true for a variety of different functional form assumptions. For example, if labor hours (or equivalently, leisure hours) are nonseparable from consumption, there is still a well-specified consumption Euler equation in which one only needs to know labor hours to condition on them. Here, for the purposes of understanding the determination of consumption, one need not know the structure of the labor market for the equation to hold, only the actual magnitudes of labor hours ground out by the labor market. (Susanto Basu and I talk about this in our still-in-the-works paper "Long-Run Labor Supply and the Elasticity of Intertemporal Substitution for Consumption.")

As another example, I have begun supervising a potential dissertation chapter looking at a model that combines many sides of the economy, but derives results that are robust to ignorance about the stochastic processes of the shocks to the economy.

One way to think about partial equilibrium is that a partial equilibrium model represents a class of general equilibrium models. Showing that something is true for an entire class of general equilibrium models can be quite useful. Therefore, partial equilibrium can be quite useful.

Where General Equilibrium Models Come In

Because of their robustness to ignorance in other parts of the economy, partial equilibrium models have a real advantage over general equilibrium models for breaking the task of figuring out how the world works into manageable pieces. This is empirical analysis, in the literal sense of analysis as breaking things down.

Once one understands (to some reasonable extent) how the world works, general equilibrium models are the way to understand what the effects of different policies would be. The motto that "Everything affects everything else" is a useful reminder that studying the effects of policies often requires a general equilibrium approach. But that comes after one understands what the right model is. Partial equilibrium is often a better way to figure out, piece by piece, what the right model and the right parameter values are.

Price Theory

Even in policy analysis, sometimes a more partial equilibrium approach can be helpful. In policy analysis, a partial equilibrium approach can be called "price theory," in line with Glen Weyl's definition in his Marginal Revolution guest post "What Is 'Price Theory'?":

... my own definition of price theory as analysis that reduces rich (e.g. high-dimensional heterogeneity, many individuals) and often incompletely specified models into ‘prices’ sufficient to characterize approximate solutions to simple (e.g. one-dimensional policy) allocative problems.

Glen gives some examples:

To illustrate my definition I highlight four distinctive characteristics of price theory that follow from this basic philosophy. First, diagrams in price theory are usually used to illustrate simple solutions to rich models, such as the supply and demand diagram, rather than primitives such as indifference curves or statistical relationships. Second, problem sets in price theory tend to ask students to address some allocative or policy question in a loosely-defined model (does the minimum wage always raise employment under monopsony?), rather than solving out completely a simple model or investigating data. Third, measurement in price theory focuses on simple statistics sufficient to answer allocative questions of interest rather than estimating a complete structural model or building inductively from data. Raj Chetty has described these metrics, often prices or elasticities of some sort, as “sufficient statistics”. Finally, price theory tends to have close connections to thermodynamics and sociology, fields that seek simple summaries of complex systems, rather than more deductive (mathematics), individual-focused (psychology) or inductive (clinical epidemiology and history) fields.

I view most of the economics I do on this blog as price theory in Glen Weyl's sense: "analysis that reduces rich and often incompletely specified models into 'prices' sufficient to characterize approximate solutions to simple allocative problems." My analysis of negative interest rate policies—and in particular what I wrote in "Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates" and "Negative Rates and the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level"—is a good example.

Conclusion

The moral is don't put unnecessary constraints on the tools you use. Use the tool that best fits the purpose. Sometimes that will be general equilibrium; sometimes it will be partial equilibrium.

Related posts: