Wallace Neutrality Roundup: QE May Work in Practice, But Can It Work in Theory?

Quantitative easing or “QE” is the large scale purchases by a central bank of long-term or risky assets. QE has been used in a big way by the Fed since the financial crisis and by the Bank of Japan since the recent Japanese election, and is an important item on the monetary policy menu of all central banks that have already lowered short-term safe rates to close to zero. Moreover, purchases by the European Central Bank of risky sovereign debt at heavily discounted market prices can rightly be seen as a form of QE–indeed, as a relatively powerful form of QE.

For monetary stimulus, I favor replacing QE by negative interest rates, made possible by a fee when private banks deposit paper currency with the central bank and establishing electronic money as the unit of account. (See “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”) But my proposal to eliminate the liquidity trap is viewed as radical enough that its near-term prospects are quite uncertain. So understanding quantitative easing (“QE”) remains of great importance for practical discussions of monetary policy. The key theoretical issue for thinking about QE is the logic of Wallace Neutrality. I wrote a lot about Wallace Neutrality in my first few months of blogging, (as you can see by going back to the beginning in 2012 in my blog archive) but haven’t written as frequently about Wallace Neutrality since I turned my attention to eliminating the zero lower bound. This post gives a roundup of some of the online discussion about Wallace Neutrality in the last year or so.

I should note that I typically don’t even realize that someone has written a response to one of my posts unless someone sends a tweet with “@mileskimball” in it, tells me in a comment, or sends me an email. So I appreciate Richard Serlin letting me know about several posts he and others have written about Wallace Neutrality.

Richard Serlin 1: Richard has two posts. In the first, published September 9, 2012, “Want to Understand the Intuition for Wallace Neutrality (QE Can’t Work), and Why it’s Wrong in the Real World?” Richard sets the stage this way:

This refers to Neil Wallace’s 1981 AER article, “A Modigliani-Miller theorem for open-market operations”. The article has been very influential today, as it has been used as a reason why quantitative easing can’t work. Here are some example quotes:

“No, in a liquidity trap, if the Fed purchases gold, it does not change the price of gold, just as it will not change the prices of Treasury bonds if it purchases them.” – Stephen Williamson

“The Fed can buy all the government debt it wants right now, and that will be irrelevant, for inflation or anything else.” – Stephen Williamson

“If it were up to me, I would have given Wallace the [Nobel] prize a long time ago, and I think Sargent would say the same. However, not everyone in the profession is aware of Wallace’s contributions, and people who are aware don’t necessarily get as excited about them as I do.” – Stephen Williamson

“…the influence of Wallace neutrality thinking on the Fed is clear from the emphasis the Fed has put on telling the world what it is going to do with interest rates in the future…I have a series of other posts also discussing Wallace neutrality. In fact, essentially all of my posts listed under Monetary Policy in the June 2012 Table of Contents are about Wallace neutrality.” – Miles KimballIn Wallace’s model, when the Fed prints money and buys up an asset with it, this affects no asset’s price, and doesn’t even change inflation! Amazing claims, but they’re mathematically proven to be true – in Wallace’s model, and with the accompanying assumptions. So the big question is, even in a model, how can claims like this make sense? What could be the intuition for that?

Brad DeLong: Richard points to this from Brad DeLong as some of the best intuition for Wallace Neutrality that he had found up to that point:

Long ago, Bernanke (2000) argued that monetary policy retains enormous power to boost production, demand, and employment even at the zero nominal lower bound to interest rates:

The general argument that the monetary authorities can increase aggregate demand and prices, even if the nominal interest rate is zero, is as follows: Money, unlike other forms of government debt, pays zero interest and has infinite maturity. The monetary authorities can issue as much money as they like. Hence, if the price level were truly independent of money issuance, then the monetary authorities could use the money they create to acquire indefinite quantities of goods and assets. This is manifestly impossible in equilibrium. Therefore money issuance must ultimately raise the price level, even if nominal interest rates are bounded at zero. This is an elementary argument, but, as we will see, it is quite corrosive of claims of monetary impotence…

His argument, however, seems subject to a powerful critique: The central bank expandeth the money stock, the central bank taketh away the money stock, blessed be the name of the central bank. In order for monetary policy to be effective at the zero nominal lower bound, expectations must be that the increases in the money stock via quantitative easing undertaken will not be unwound in the future after the economy exits from its liquidity trap. If expectations are that they will be unwound, then there is potentially money to be made by taking the other side of the transaction: sell bonds to the central bank now when their prices are high, hold onto the cash until the economy exits from the liquidity trap, and then buy the bonds back from the central bank in the future when it is trying to unwind its quantitative easing policies. A Modigliani Miller-like result applies.

Richard Serlin 1 Again: Richard then gives this rundown of Neil Wallace’s paper itself:

The government prints dollars and buys the single consumption good, which I like to call c’s….

People are going to want to store a certain amount of c’s anyway, because that’s utility maximizing to help smooth consumption. What the government essentially does in this model is say, hey, store your c’s with us instead of at the private storage facility. Give us a c, and we’ll give you some dollars, which are like a receipt, or bond. We’ll then store the c’s – we won’t consume them, we won’t use them for anything (these are crucial assumptions of Wallace, required to get his stunning results) – We will just hold them in storage (implied in the equations, not stated explicitly).

Next period, you give us back those dollars, and we give you back your c’s, plus some return (from the dollar per c price changing over that period). In equilibrium, the return from storing c’s via the dollar route must be equal to the return from storing c’s via the private storage facility route. Or at least the return must be worth the same amount at the equilibrium state prices; so either way you go you can arrange at the same cost in today c’s, the same exact next period payoff in any state that can occur….

It is analogous to Miller-Modigliani, in that if a corporation increases its debt holding, then shareholders will just decrease their personal debt holding by an equivalent amount, so that their total debt stays exactly where it was, which was the amount they had previously calculated to be utility maximizing for them (And there’s a lot of very unrealistic and material assumptions that go with this that have been long acknowledged as such in academic and practitioner finance; when you learn Miller-Modigliani, at the bachelors, masters, and PhD levels – which I have – they always start by teaching the model and its strong assumptions, and then go into the various reasons why it far from holds in reality. This is long accepted in academic finance; pick up any text that covers MM.)

Richard offers one other intuition for Wallace Neutrality, based on asset pricing principles when asset prices are at their fundamental values:

Suppose dollars are printed and used to buy 10 year T-bonds. Or gold, like in the Stephen Williamson quote at the beginning of this post. And everybody knows (making a Wallace-like assumption) that in five years the T-bonds or gold will be sold back for dollars. We’re making all of the perfect assumptions here: For all investors, perfect information, perfect foresight, perfect analysis, perfect rationality, perfect liquidity,…

Now, what is the price of gold? How is it calculated in this world of perfects?

Well, as a financial asset it’s worth only what it’s future cash flows are. Suppose you are going to hold onto the gold and sell it in one year. Then, what it’s worth is its price in one year (which you know at least in every state – perfect foresight) discounted back to the present at the appropriate discount rate.

But suppose this: During that year that you will be holding the gold in your vault, you are told the government will borrow your gold for five minutes, take it out of your vault, and replace it with green slips of paper with dead presidents, then five minutes later they will take back the green slips and replace back your gold in the vault. Do you really care? This doesn’t affect how much you will get for the gold when you sell it in a year, and as a financial asset that’s all you care about when you decide how much gold is worth today.

If you’re going to hold the gold for ten years, and sell it then, then you only care about what the price of gold will be in ten years. And the price of gold in ten years only depends on what the supply and demand for gold is in ten years. If the government takes 100 million ounces of gold out of private vaults, and put it in its vaults, then puts it back in the private vaults three years later, this has no effect on the supply of gold in ten years. So in ten years the price of gold is the same. And if gold will be the same price in ten years, then it will be worth the same price today for someone who’s not going to sell for ten years anyway.

Jérémie Cohen-Setton and Éric Monnet: A year later, September 6, 2012, Richard wrote a follow-up post: The Intuition for Wallace Neutrality, Part II: Why it doesn’t Work in the Real World. Richard flags an excellent synthesis by Jérémie Cohen-Setton and Éric Monnet on 10th September 2012: Blogs review: Wallace Neutrality and Balance Sheet Monetary Policy. Jérémie and Éric start by explaining why understanding the issues surrounding Wallace Neutrality matters in the real world, with particular reference to Mike Woodford’s conclusions assuming Wallace Neutrality, and then give this summary discussions of Wallace Neutrality by Richard, Brad DeLong, Michael Woodford and me:

Miles Kimball defines Wallace neutrality as follows: a property of monetary economic models in which differences in the government’s overall balance sheet at moments in time when the nominal interest rate is zero have no general equilibrium effect on interest rates, prices, or non-financial economic activity. Richard Serlin (HT Mark Thoma) writes that in Wallace’s model, when the Fed prints money and buys up an asset with it, this affects no asset’s price, and doesn’t even change inflation!

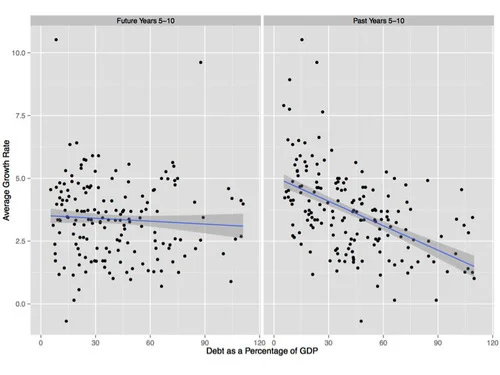

Brad DeLong and Miles Kimball think that Wallace neutrality has baseline modeling status, in the same manner as Ricardian neutrality. Saying a model has baseline modeling status is saying that it should be the starting point for thinking about how the world works – as it reflects how the simplest economics models behave within the category of “optimizing models.”. The discussion is then about what might plausibly make things behave differently in the real world from that theoretical starting point. Miles Kimball argues that the difference in the theoretical status of Wallace neutrality as compared to Ricardian neutrality is that we are earlier in the process of putting together good models of why the real world departs from Wallace neutrality. Studying theoretical reasons why the world might not obey Ricardian neutrality was frontier research 25 years ago. Showing theoretical reasons why the world might not obey Wallace neutrality is frontier research now….

As far as intuition for Wallace Neutrality goes, here is Jérémie and Éric channeling Mike Woodford:

Michael Woodford notes that it is important to note that such “portfolio-balance effects” do not exist in a modern, general-equilibrium theory of asset prices. Within this framework the market price of any asset should be determined by the present value of the random returns to which it is a claim, where the present value is calculated using an asset pricing kernel (stochastic discount factor) derived from the representative household’s marginal utility of income in different future states of the world. Insofar as a mere re-shuffling of assets between the central bank and the private sector should not change the real quantity of resources available for consumption in each state of the world, the representative household’s marginal utility of income in different states of the world should not change. Hence the pricing kernel should not change, and the market price of one unit of a given asset should not change, either, assuming that the risky returns to which the asset represents a claim have not changed.

On reasons why Wallace Neutrality might not hold in the real world, I am pleased to see that Jérémie and Éric reference the Wikipedia article on Wallace Neutrality that Fudong Zhang got started:

The Wikipedia page for Wallace Neutrality – the result of a proposed public service provided by the readers of the Miles Kimball’s blog, Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal – point to other recent works which invalidate Wallace neutrality based on different relaxed assumptions and novel mechanisms. For example, in Andrew Nowobilski’s (2012) paper, open market operations powerfully influence economic outcomes due to the introduction of a financial sector engaging in liquidity transformation.

Richard Serlin 2: Now for the core of what Richard says in his second post, The Intuition for Wallace Neutrality, Part II: Why it doesn’t Work in the Real World. Richard has kindly given me permission to quote at some length from his nice explanation of the logic behind Wallace Neutrality and why it might not hold in the real world:

I had gone down various roads in thinking about why the neutrality that worked in Wallace’s model would not work in the real world, and I just wasn’t able to really nail down any of them the way I wanted to, at least not the ones I wanted to. But thinking about this again, the idea came to me. The intuition is this:

Suppose the Fed does buy up 100 million ounces of gold in a quantitative easing. And the people who are savvy, well informed, expert, and rational know that in some years the economy will turn around, and the Fed will just sell back all of those 100 million ounces. So, in 10 years, the supply of gold will be the same as it would have been if the quantitative easing had never occurred. The ownership papers will shift from private parties to the federal government in the interim, but will be back again to private parties like they never left in 10 years. So, no fundamental change to the asset’s value in 10 years.

And if no fundamental change to the asset’s value in 10 years, then no fundamental change to the asset’s value today, as the value today, for a financial asset with no dividends, coupons, etc., is just the discounted present value of the asset’s value 10 years from now.

Now, as should be obvious – especially with gold – not all investors are savvy, well informed, expert, and rational – let alone sane! So, when the price of gold starts to go up, some of them will not sell at that higher price, even though fundamentally the price should not go higher; nothing has changed about the long run, or 10 year, price of gold.

In the Wallace model, and commonly in financial economics models, no problem, arbitrage opportunity! Suppose there are investors who are less than perfectly expert, knowledgeable, and rational – or way less – and they don’t sell when the government buys up the price a little. Who cares. It just takes one expert knowledgeable investor to recognize that there’s an arbitrage opportunity when the price of gold goes up merely because the government is buying it in a QE, and he’ll milk it ceaselessly until the price is all the way back down again and the arbitrage disappears….

Now, for this to work as advertised, first you need 100% complete markets, so you must have a primitive asset (or be able to synthetically construct one) for every possible state at every possible time in the world.

[using Chandler Bing voice] Have you seeeen our world? The number of states just one minute from now is basically infinite. Even the number of significant finitized states over the next day, let alone a path of years, is so large, it’s for all intents and purposes infinite. Thus, try to construct a synthetic asset that pays off the same as gold, now and over time, and you’re not going to come very close. And if you try buying it to sell gold, or vice versa, to get an “arbitrage”, you’re going to expose yourself to a lot of risk.

And this is a key. I think a lot of misunderstanding comes from loose use of the word “arbitrage”. The textbook definition of arbitrage is a set of transactions that has zero risk, zero. It’s 100% risk free. It’s not low risk, as often things that are called arbitrage are. It’s not 99% risk-free. It’s riskless, zero. That’s what makes it so powerful in models, at least one of the things.

Another one of the things that makes it so powerful in models is that it requires none of your own money. If there’s an expert and informed enough investor anywhere, even just a single one, who sees it, it doesn’t matter if he doesn’t have two nickels to rub together, he can do it. He can borrow the money to buy the assets necessary, and at the market interest rate. Or, he can just sign the necessary contracts, for whatever amounts, no matter how big. His credit and credibility are always considered good enough….

Well, what are the problems with that? The usual one you hear is that savvy investors are only a small minority of all investors, and this is especially true of highly expert investors who are highly informed about a given individual asset, or even asset class. And they only have so much money. Eventually, if the government keeps buying in a QE it could exhaust their funds, their ability to counter, by, for example, selling gold they own, or selling gold they don’t own short.

Even rich people and institutions only have so much money and liquidity, or credit. You can’t outlast the Fed, if the Fed is truly determined. Your pockets may be very deep, but the Fed’s pockets are infinite.

So, you usually hear that.

But there’s another reason why the savvy marginal investor is limited in his ability and willingness to push prices back to their fundamentals that I never hear. It’s a powerful and important reason: The more a savvy investor jumps on a mispriced individual asset, the more his portfolio gets undiversified, and that can quickly become dangerous and not worth it.

Miles: Despite having turned my primary attention in relation to monetary policy to eliminating the zero lower bound, I have written a fair amount about QE in the last year. My column “Why the US Needs Its Own Sovereign Wealth Fund” discusses my intuition that Wallace Neutrality will be further from the truth for assets that have the largest risk and term premiums and what this suggests for monetary policy, given that the Fed doesn’t have non-emergency authority to buy corporate stocks and bonds:

…what if longer-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities are the wrong assets for the Fed to buy? Most of those rates are already below 3%, so it’s not that easy to push the rates down further. What is worse, when long-term assets already have low interest rates, pushing down those interest rates pushes the prices of those assets up dramatically. So the Fed ends up paying a lot for those assets, and when it later has to turn around and sell them—as it ultimately will need to, to raise interest rates and avoid inflation, it will lose money. Avoiding buying high and selling low is tough when the Fed has to move interest rates to do the job it needs to do. At least economic recovery reduces mortgage defaults and so helps raise the prices of mortgage-backed securities through that channel. But the effects of interest rates on long-term assets cut against the Fed’s bottom line in a way that is never an issue when the Fed buys and sells 3-month Treasury bills in garden-variety monetary policy.

From a technical point of view, once 3-month Treasury bill rates (and overnight federal funds rates) are near zero, the ideal types of assets for “quantitative easing” to work with are assets that (a) have interest rates far above zero and (b) are buoyed up in price when the economy does well. That means the ideal assets for quantitative easing are stock index funds or junk bond funds!

Yet, is the Federal Reserve even the right institution to be making investment decisions like this?…

Why not create a separate government agency to run a US sovereign wealth fund? Then the Fed can stick to what it does best—keeping the economy on track—while the sovereign wealth fund takes the political heat, gives the Fed running room, and concentrates on making a profit that can reduce our national debt….

As an adjunct to monetary policy, the details of what a US Sovereign Wealth Fund buys don’t matter. As long as the fund focuses on assets with high rates of return, the effect on the economy will be stimulative, and the Fed can use its normal tools to keep the economy from getting too much stimulus.

In May 2013, I wrote a full column on quantitative easing: “QE or not QE: Even Economists Need Lessons in Quantitative Easing, Bernanke Style,” sparked by a Martin Feldstein column. There, in relation to Wallace Neutrality, I write:

Once the Fed has hit the “zero lower bound,” it has to get more creative. What quantitative easing does is to compress—that is, squish down—the degree to which long-term and risky interest rates are higher than safe, short-term interest rates. The degree to which one interest rate is above another is called a “spread.” So what quantitative easing does is to squish down spreads. Since all interest rates matter for economic activity, if safe short-term interest rates stay at about zero, while long-term and risky interest rates get pushed down closer to zero, it will stimulate the economy. When firms and households borrow, the markets treat their debt as risky. And firms and households often want to borrow long term. So reducing risky and long-term interest rates makes it less expensive to borrow to buy equipment, hire coders to write software, build a factory, or build a house.

Some of the confusion around quantitative easing comes from the fact that in the kind of economic models that come most naturally to economists, in which everyone in sight is making perfect, deeply-insightful decisions given their situation, and financial traders can easily borrow as much as they want to, quantitative easing would have no effect. In those “frictionless” models, financial traders would just do the opposite of whatever the Fed does with quantitative easing, and cancel out all the effects. But it is important to understand that in these frictionless models where quantitative easing gets cancelled out, it has no important effects. Because in the frictionless models quantitative easing gets canceled out, it doesn’t stimulate the economy. But because in the frictionless models quantitative easing gets cancelled out it has no important effects. In the world where quantitative easing does nothing, it also has no side effects and no dangers. Any possible dangers of quantitative easing only occur in a world where quantitative easing actually works to stimulate the economy!

Now it should not surprise anyone that the world we live in does have frictions. People in financial markets do not always make perfect, deeply-insightful decisions: they often do nothing when they should have done something, and something when they should have done nothing. And financial traders cannot always borrow as much as they want, for as long as they want, to execute their bets against the Fed, as Berkeley professor and prominent economics blogger Brad DeLong explains entertainingly and effectively in “Moby Ben, or, the Washington Super-Whale: Hedge Fundies, the Federal Reserve, and Bernanke-Hatred.” But there is an important message in the way quantitative easing gets canceled out in frictionless economic models. Even in the real world, large doses of quantitative easing are needed to get the job done, since real-world financial traders do manage to counteract some of the effects of quantitative easing as they go about their normal business of trying to make good returns. And “large doses” means Fed purchases of long-term government bonds and mortgage-backed bonds that run into trillions and trillions of dollars. (As I discuss in “Why the US Needs Its Own Sovereign Wealth Fund,” quantitative easing would be more powerful if it involved buying corporate stocks and bonds instead of only long-term government bonds and mortgage-backed bonds.) It would have been a good idea for the Fed to do two or three times as much quantitative easing as it did early on in the recession, though there are currently enough signs of economic revival that it is unclear how much bigger the appropriate dosage is now….

Sometimes friction is a negative thing—something that engineers fight with grease and ball bearings. But if you are walking on ice across a frozen river, the little bit of friction still there between your boots and the ice allow you to get to the other side. It takes a lot of doing, but quantitative easing uses what friction there is in financial markets to help get us past our economic troubles.

In response to one commenter (by email) who thought that QE had not done much either for the stock market or the economy as a whole, I wrote:

But this seems like an argument for a bigger dosage of QE. And it is not clear that the counterfactual is share prices staying the same. Without any QE, the economy would probably have been hurting enough that stock prices would have gone down….

The key point I am trying to make is that it is the ratio of stimulus to undesirable side-effect that matters, not the ratio of stimulus to dollar size of asset purchase. I think you are saying that the Fed has done a lot of QE with relatively little effect, but to the extent that the QE has relatively little effect in undesirable directions as well as relatively little effect in terms of stimulus, the answer is simply to scale up the size of the asset purchases. For example, if a given level of QE has little effect on the level of stock prices and therefore little stimulus, it presumably has relatively little effect on financial stability as well, to the extent financial stability worries have to do with the level of the stock market.

The one undesirable effect I know of that depends on the size of the asset purchase *as opposed to the size of the stimulus generated,* is the capital losses the Fed will face when it sells the long-term bonds. That is something I write about in my column advocating a US Sovereign Wealth Fund as a way to do a fixed quantum of QE that focuses on assets that would gain more in value from general equilibrium effects than long-term government bonds would: “Why the US Needs Its Own Sovereign Wealth Fund.”

The point

…it is the ratio of stimulus to undesirable side-effect that matters, not the ratio of stimulus to dollar size of asset purchase.

is of course the point I was making in my first post on Wallace Neutrality (and second post on QE) back in June 2012,

“Trillions and Trillions: Getting Used to Balance Sheet Monetary Policy." (There is a similar point in my working paper "Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy” about National Lines of Credit.“You can read the blog post here, which has a link to the paper.)