Why I am a Macroeconomist: Increasing Returns and Unemployment

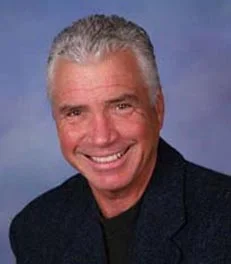

During my first year in Harvard’s Economic Ph.D. program (1983-1984), I thought to myself I could never be a macroeconomist, because I couldn’t figure out where the equations came from in the macro papers we were studying. In my second year, I focused on microeconomic theory, with Andreu Mas-Colell as my main role model. Then, during the first few months of calendar 1985, I stumbled across Martin Weitzman’s paper “Increasing Returns and the Foundations of Unemployment Theory” in the Economics Department library. Marty’s paper made me decide to be a macroeconomist. (I took the macroeconomics field courses and began working on writing some macroeconomics papers the following year, my third year–the year Greg Mankiw joined the Harvard faculty–and went on the job market in my fourth year.) I want to give you some of the highlights from “Increasing Returns and the Foundations of Unemployment Theory”, not only so you can see what affected me so strongly, but also because it includes ideas that every serious economist should have in his or her mental arsenal. Marty’s paper is a “big-think” paper. It has a lot to say, even after all of the equations were stripped out of it.

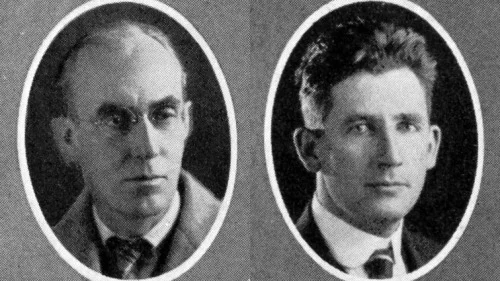

There is one important piece of background before turning to Marty’s paper: Say’s Law. In Say’s own words, organized by the wikipedia article on Say’s Law:

In Say’s language, “products are paid for with products” (1803: p. 153) or “a glut can take place only when there are too many means of production applied to one kind of product and not enough to another” (1803: p. 178-9). Explaining his point at length, he wrote that:

It is worthwhile to remark that a product is no sooner created than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. Thus the mere circumstance of creation of one product immediately opens a vent for other products. (J. B. Say, 1803: pp.138–9)

Say’s Law is sometimes expressed as “Supply creates its own demand.” Say’s law seems to deny the possibility of Keynesian unemployment–unemployed workers who are identical in their productivity to workers who have jobs, and are willing to work for the same wages, but cannot find a job in a reasonable amount of time. The argument of Say’s law needs to be countered in some way in order to argue for the existence of Keynesian unemployment. Marty paints of picture of Keynesian unemployment in this way:

In a modern economy, many different goods are produced and consumed. Each firm is a specialist in production, while its workers are generalists in consumption. Workers receive a wage from the firm they work for, but they spend it almost entirely on the products of other firms. To obtain a wage, the unemployed worker must first succeed in being hired. However, when demand is depressed because of unemployment, each firm sees no indication it can profitably market the increased output of an extra worker. The inability of the unemployed to communicate effective demand results in a vicious circle of self-sustaining involuntary unemployment. There is an atmosphere of frustration because the problem is beyond the power of any single firm to correct, yet would go away if only all firms would simultaneously expand output. It is difficult to describe this kind of ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ unemployment rigorously, much less explain it, in an artificially aggregated economy that produces essentially one good.

Marty mentions one economic fact that has big implications even outside of business cycle theory. A remarkable fact about the political economy of trade is that trade policy often favors the interests of producers over the interests of consumers. Why are producer lobbies more powerful than consumer lobbies? The key underlying fact is that “Each firm is a specialist in production, while its workers are generalists in consumption.” So particular firms and the workers of those firms care a huge amount about trade policy for the good that they make, while the many consumers who would each benefit a little from a lower price with free imports are not focused on the issue of that particular good, since it is only a small share of their overall consumption. The exceptions, where consumer interests take the front seat in policy making, are typically where the good in question is a very large share of the consumption bundle (such as wheat or rice in poor countries) or where trade policy for many different goods has been combined into an overall trade package that could make a noticeable difference for an individual consumer. Other political actions that depart from the free market often follow a similar principle–either favoring a producer or favoring households interests in relation to a good that is a large share of the household’s budget, such as rent, or a very salient good such as gasoline, which seems to consumers as if it is even more important for their budgets than it really is.

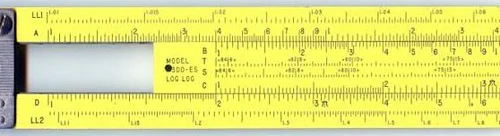

After painting the picture of the world that he wants to provide a foundation for, Marty dives into his main argument–that increasing returns is essential if one wants to explain unemployment.

In this paper I want to argue that the ultimate source of unemployment equilibrium is increasing returns. When compared at the same level of aggregation, the fundamental differences between classical and unemployment versions of general equilibrium theory trace back to the issue of returns to scale.

More formally, I hope to show that the very logic of strict constant returns to scale (plus symmetric information) must imply full employment, whereas unemployment can occur quite naturally with increasing returns

He argues that much the same issues would arise from increasing returns to scale from a wide variety of difference causes:

The reasons for increasing returns are anything that makes average productivity increase with scale - such as physical economies of area or volume, the internalisation of positive externalities, economising on information or transactions, use of inanimate power, division of labour, specialisation of roles or functions, standardisation of parts, the law of large numbers, access to financial capital, etc., etc.

Marty lays out a sequence of three models. Here are the first two models or “stages”:

III. STAGE I: SELF SUFFICIENCY

Suppose each labourer can produce α units of any commodity. In such a world the economic problem has a trivial Robinson Crusoe solution. A person of attribute type i simply produces and consumes α units of commodity i.

IV. STAGE II: SMALL SCALE SPECIALISATION

Now suppose a person of type (i,j) prefers to consume i but has a comparative advantage in producing j.

In such an economy there can be no true unemployment because there are no true firms. If anyone is declared 'unemployed’ by a firm, he can just announce his own miniature firm, hire himself, and sell the product directly on a perfectly competitive market.

In the context of the “Stage II” model, Marty points to increasing returns to scale not only as the explanation for unemployment, but also as what makes plants discrete entities (in this paper he does not distinguish between plants and firms):

In a constant returns economy the firm is an artificial entity. It does not matter how the boundary of a firm is drawn or even if it is drawn at all. There is no operational distinction between the size of a firm and the number of firms.

Also, increasing returns to scale is the reason it is typical for a firm, defined in important measure by its capital, to hire workers, rather than the other way around. With constant returns to scale, workers could easily hire capital and there would be less unemployment:

When unemployed factor units are all going about their business spontaneously employing themselves or being employed, the economy will automatically break out of unemployment.

One reason increasing returns to scale is so powerful in its effects is that it is closely linked to imperfect competition–as constant returns to scale is closely linked to perfect competition.

The seemingly institution-free or purely technological question of the extent of increasing returns is a loaded issue precisely because the existence of pure competition is at stake.

To emphasise a basic truth dramatically, let the case be overstated here. Increasing returns, understood in its broadest sense, is the natural enemy of pure competition and the primary cause of imperfect competition. (Leave aside such rarities as the monopoly ownership of a particular factor.)

After laying out a particular macroeconomic model with increasing returns to scale, Marty directly addresses Say’s law, writing this:

Behind a mathematical veneer, the arguments used in the new classical macroeconomics to discredit steady state involuntary unemployment are implicitly based on some version or other of Say’s Law. It is true that under strict constant returns to scale and perfect competition, Say’s Law will operate to ensure that involuntary unemployment is automatically eliminated by the self interested actions of economic agents. Each existing or potential firm knows that irrespective of what the other firms do it cannot glut its own market by unilaterally expanding production, hence a balanced expansion of the entire underemployed econorny in fact takes place. But increasing returns prevents supply from creating its own demand because the unemployed workers are essentially blocked from producing. Either the existing firms will not hire them given the current state of demand, or, even if a group of unemployed workers can be coalesced effectively into a discrete lump of new supply, it will spoil the market price before ever giving Say’s Law a chance to start operating. When each firm is afraid of glutting its own local market by unilaterally increasing output, the economy can get trapped in a low level equilibrium simply because there is insufficient pressure for the balanced simultaneous expansion of all markets. Correcting this 'externality’, if that is how it is viewed, requires nothing less than economy-wide coordination or stimulation. The usual invisible hand stories about the corrective powers of arbitrage do not apply to effective demand failures of the type considered here.

To this day–more than 27 years later–I stand convinced that increasing returns to scale are essential to understanding macroeconomics in the real world. Much of what we see around us stems from the inability of half a factory, staffed with half as many workers, to produce half the output. Despite the difficulty of explaining Marty’s logic for why increasing returns to scale matters and what its detailed consequences are, I believe Intermediate Macroeconomics textbooks–and even Principles of Macroeconomics textbooks–need to try. Anyone who learns much macroeconomics at all should not be denied a chance to hear some of Marty’s logic.