Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia Can Prevent Major Depression

Why do we care about causality? The primary reason is that we are looking for interventions that can make things better. Some causal results give only one part of the puzzle of designing an intervention to make things better, while other causal results directly recommend an intervention once combined with a reasonable judgment about what constitutes “better.”

The result in “Prevention of Incident and Recurrent Major Depression in Older Adults With Insomnia” by Michael R. Irwin, Carmen Carrillo, Nina Sadeghi, Martin F. Bjurstrom, Elizabeth C. Breen, and Richard Olmstead that “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia” (CBT-I) applied to adults 60 years or older who have insomnia, but don’t initially qualify as having major depression both reduces insomnia and reduces the incidence of major depression. This is a very useful thing to know.

It is tempting to interpret this result as strong evidence that insomnia causes an increased incidence of major depression. It is quite plausible that is true, since many experiments show that extreme sleep deprivation (or extreme deprivation of just REM—dreaming—sleep) quickly causes people to go crazy. But underlying subclinical depression could easily disrupt sleep, so there is a real possibility of reverse causality. And as a statistical instrument, CBT-I does not satisfy the exclusion restriction: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) in general is known to have a powerful effect in reducing depression even in people who don’t have insomnia. So the CBT elements in CBT-I are likely to have a direct effect in reducing depression that doesn’t all work through reducing insomnia.

What about fact that those whose insomnia lessened were especially likely to have a reduction in incidence of major depression? I am thinking of this result:

Those in the CBT-I group with sustained remission of insomnia disorder had an 82.6% decreased likelihood of depression (hazard ratio, 0.17; 95%, CI 0.04-0.73; P = .02) compared with those in the SET group without sustained remission of insomnia disorder.

That can be explained simply by lessened insomnia being a sign that the CBT principles “took” for that individual. That is, CBT is going to work better for some people than others, if only because after being taught CBT principles, some people will really use those principles in their lives and others won’t. If CBT “takes” for an individual, it can have benefits in multiple areas.

Should we care whether reduction in insomnia is the pathway by which CBT-I reduces the incidence of depression? Not if CBT-I is, and would stay, the only effective treatment for insomnia. But when there is another effective treatment for insomnia, it matters. Whether that other treatment for insomnia will reduce the incidence of depression depends on the extent to which the pathway by which CBT-I reduce depression is through lessening insomnia. The best way to find that out is to do a similar study with other effective treatments for insomnia. If enough different effective treatments for insomnia also reduce the incidence of depression, that raises confidence that the next effective treatment for insomnia will also reduce the incidence of depression, which is the most important practical thing we would mean by claiming that insomnia causes a higher incidence of depression.

Statistically, many different effective treatments for insomnia reducing the incidence of depression would make it more likely that at least one of those treatments approximately satisfied the exclusion restriction by not having a big direct effect on incidence of depression. Note how that would depend on how different the “different effective treatments for insomnia” are. For example, in the extreme, if they were all minor variations on CBT-I, then they don’t lend much additional evidentiary weight to the claim that insomnia causes a higher incidence of depression.

The Federalist Papers #54: Defending the Indefensible—How Attempting to Justify the 3/5 Rule for Slaves Digs the Hole Deeper

The Federalist Papers #54 provides some evidence for those who want to argue that—to an important but not total extent—the United States of America was founded on slavery. And what the Federalist Papers #54 says about slavery is only part of its horror. Below, let me lay out some of the passages that are rightly shocking to modern sensibilities, separated passages by added bullets. On slavery:

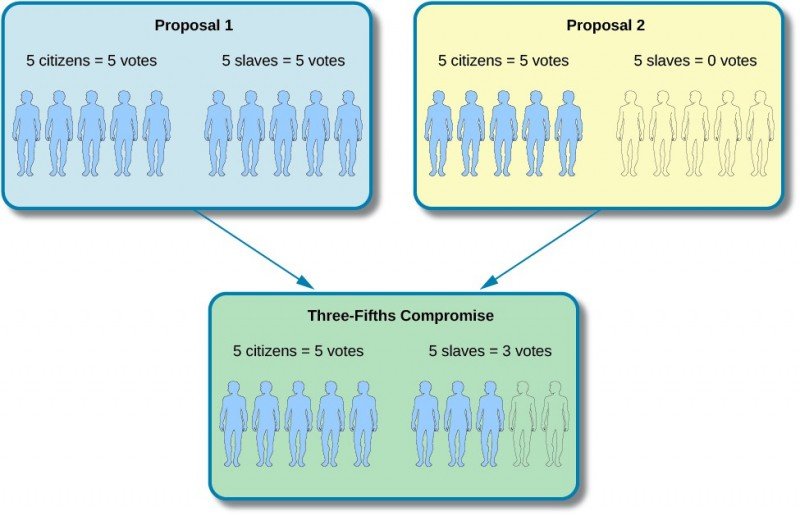

All this is admitted, it will perhaps be said; but does it follow, from an admission of numbers for the measure of representation, or of slaves combined with free citizens as a ratio of taxation, that slaves ought to be included in the numerical rule of representation? Slaves are considered as property, not as persons. They ought therefore to be comprehended in estimates of taxation which are founded on property, and to be excluded from representation which is regulated by a census of persons. This is the objection, as I understand it, stated in its full force.

… representation relates more immediately to persons, and taxation more immediately to property, and we join in the application of this distinction to the case of our slaves.

But we must deny the fact, that slaves are considered merely as property, and in no respect whatever as persons. The true state of the case is, that they partake of both these qualities: being considered by our laws, in some respects, as persons, and in other respects as property.

In being compelled to labor, not for himself, but for a master; in being vendible by one master to another master; and in being subject at all times to be restrained in his liberty and chastised in his body, by the capricious will of another, the slave may appear to be degraded from the human rank, and classed with those irrational animals which fall under the legal denomination of property. In being protected, on the other hand, in his life and in his limbs, against the violence of all others, even the master of his labor and his liberty; and in being punishable himself for all violence committed against others, the slave is no less evidently regarded by the law as a member of the society, not as a part of the irrational creation; as a moral person, not as a mere article of property. The federal Constitution, therefore, decides with great propriety on the case of our slaves, when it views them in the mixed character of persons and of property. This is in fact their true character.

Could it be reasonably expected, that the Southern States would concur in a system, which considered their slaves in some degree as men, when burdens were to be imposed, but refused to consider them in the same light, when advantages were to be conferred?

Let the case of the slaves be considered, as it is in truth, a peculiar one. Let the compromising expedient of the Constitution be mutually adopted, which regards them as inhabitants, but as debased by servitude below the equal level of free inhabitants, which regards the SLAVE as divested of two fifths of the MAN.

Such is the reasoning which an advocate for the Southern interests might employ on this subject; and although it may appear to be a little strained in some points, yet, on the whole, I must confess that it fully reconciles me to the scale of representation which the convention have established.

Saying that wealth or “property” is a legitimate basis of political power:

Government is instituted no less for protection of the property, than of the persons, of individuals. The one as well as the other, therefore, may be considered as represented by those who are charged with the government. Upon this principle it is, that in several of the States, and particularly in the State of New York, one branch of the government is intended more especially to be the guardian of property, and is accordingly elected by that part of the society which is most interested in this object of government.

It is a fundamental principle of the proposed Constitution, that as the aggregate number of representatives allotted to the several States is to be determined by a federal rule, founded on the aggregate number of inhabitants, so the right of choosing this allotted number in each State is to be exercised by such part of the inhabitants as the State itself may designate. The qualifications on which the right of suffrage depend are not, perhaps, the same in any two States. In some of the States the difference is very material. In every State, a certain proportion of inhabitants are deprived of this right by the constitution of the State, who will be included in the census by which the federal Constitution apportions the representatives.

Nor will the representatives of the larger and richer States possess any other advantage in the federal legislature, over the representatives of other States, than what may result from their superior number alone. As far, therefore, as their superior wealth and weight may justly entitle them to any advantage, it ought to be secured to them by a superior share of representation.

Not every idea in the Federalist Papers #54 is bad. This bit—logically separable from the horrifying bits—one can agree with:

In one respect, the establishment of a common measure for representation and taxation will have a very salutary effect. As the accuracy of the census to be obtained by the Congress will necessarily depend, in a considerable degree on the disposition, if not on the co-operation, of the States, it is of great importance that the States should feel as little bias as possible, to swell or to reduce the amount of their numbers. Were their share of representation alone to be governed by this rule, they would have an interest in exaggerating their inhabitants. Were the rule to decide their share of taxation alone, a contrary temptation would prevail. By extending the rule to both objects, the States will have opposite interests, which will control and balance each other, and produce the requisite impartiality.

Below is the full text of the Federalist Papers #54, to show that I have not misrepresented the thrust of this number, which is quite willing to accommodate slavery for the sake of having states that are into slavery in a big way assent to union with the other states. The author of this number (Alexander Hamilton or James Madison) is sometimes putting an argument of another imagined interlocutor, but everything I quote above about slavery is treated by the author as a reasonable argument with no hint of strong disagreement. The author actually distances himself most from anti-slavery attitudes—as you can see from this bit:

Might not some surprise also be expressed, that those who reproach the Southern States with the barbarous policy of considering as property a part of their human brethren …

FEDERALIST NO. 54

The Apportionment of Members Among the States

From the New York Packet

Tuesday, February 12, 1788.

Author: Alexander Hamilton or James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

THE next view which I shall take of the House of Representatives relates to the appointment of its members to the several States which is to be determined by the same rule with that of direct taxes. It is not contended that the number of people in each State ought not to be the standard for regulating the proportion of those who are to represent the people of each State. The establishment of the same rule for the appointment of taxes, will probably be as little contested; though the rule itself in this case, is by no means founded on the same principle. In the former case, the rule is understood to refer to the personal rights of the people, with which it has a natural and universal connection.

In the latter, it has reference to the proportion of wealth, of which it is in no case a precise measure, and in ordinary cases a very unfit one. But notwithstanding the imperfection of the rule as applied to the relative wealth and contributions of the States, it is evidently the least objectionable among the practicable rules, and had too recently obtained the general sanction of America, not to have found a ready preference with the convention. All this is admitted, it will perhaps be said; but does it follow, from an admission of numbers for the measure of representation, or of slaves combined with free citizens as a ratio of taxation, that slaves ought to be included in the numerical rule of representation? Slaves are considered as property, not as persons. They ought therefore to be comprehended in estimates of taxation which are founded on property, and to be excluded from representation which is regulated by a census of persons. This is the objection, as I understand it, stated in its full force. I shall be equally candid in stating the reasoning which may be offered on the opposite side. "We subscribe to the doctrine," might one of our Southern brethren observe, "that representation relates more immediately to persons, and taxation more immediately to property, and we join in the application of this distinction to the case of our slaves. But we must deny the fact, that slaves are considered merely as property, and in no respect whatever as persons. The true state of the case is, that they partake of both these qualities: being considered by our laws, in some respects, as persons, and in other respects as property. In being compelled to labor, not for himself, but for a master; in being vendible by one master to another master; and in being subject at all times to be restrained in his liberty and chastised in his body, by the capricious will of another, the slave may appear to be degraded from the human rank, and classed with those irrational animals which fall under the legal denomination of property. In being protected, on the other hand, in his life and in his limbs, against the violence of all others, even the master of his labor and his liberty; and in being punishable himself for all violence committed against others, the slave is no less evidently regarded by the law as a member of the society, not as a part of the irrational creation; as a moral person, not as a mere article of property. The federal Constitution, therefore, decides with great propriety on the case of our slaves, when it views them in the mixed character of persons and of property. This is in fact their true character. It is the character bestowed on them by the laws under which they live; and it will not be denied, that these are the proper criterion; because it is only under the pretext that the laws have transformed the negroes into subjects of property, that a place is disputed them in the computation of numbers; and it is admitted, that if the laws were to restore the rights which have been taken away, the negroes could no longer be refused an equal share of representation with the other inhabitants. "This question may be placed in another light. It is agreed on all sides, that numbers are the best scale of wealth and taxation, as they are the only proper scale of representation. Would the convention have been impartial or consistent, if they had rejected the slaves from the list of inhabitants, when the shares of representation were to be calculated, and inserted them on the lists when the tariff of contributions was to be adjusted? Could it be reasonably expected, that the Southern States would concur in a system, which considered their slaves in some degree as men, when burdens were to be imposed, but refused to consider them in the same light, when advantages were to be conferred? Might not some surprise also be expressed, that those who reproach the Southern States with the barbarous policy of considering as property a part of their human brethren, should themselves contend, that the government to which all the States are to be parties, ought to consider this unfortunate race more completely in the unnatural light of property, than the very laws of which they complain? "It may be replied, perhaps, that slaves are not included in the estimate of representatives in any of the States possessing them. They neither vote themselves nor increase the votes of their masters. Upon what principle, then, ought they to be taken into the federal estimate of representation? In rejecting them altogether, the Constitution would, in this respect, have followed the very laws which have been appealed to as the proper guide. "This objection is repelled by a single observation. It is a fundamental principle of the proposed Constitution, that as the aggregate number of representatives allotted to the several States is to be determined by a federal rule, founded on the aggregate number of inhabitants, so the right of choosing this allotted number in each State is to be exercised by such part of the inhabitants as the State itself may designate. The qualifications on which the right of suffrage depend are not, perhaps, the same in any two States. In some of the States the difference is very material. In every State, a certain proportion of inhabitants are deprived of this right by the constitution of the State, who will be included in the census by which the federal Constitution apportions the representatives.

In this point of view the Southern States might retort the complaint, by insisting that the principle laid down by the convention required that no regard should be had to the policy of particular States towards their own inhabitants; and consequently, that the slaves, as inhabitants, should have been admitted into the census according to their full number, in like manner with other inhabitants, who, by the policy of other States, are not admitted to all the rights of citizens. A rigorous adherence, however, to this principle, is waived by those who would be gainers by it. All that they ask is that equal moderation be shown on the other side. Let the case of the slaves be considered, as it is in truth, a peculiar one. Let the compromising expedient of the Constitution be mutually adopted, which regards them as inhabitants, but as debased by servitude below the equal level of free inhabitants, which regards the SLAVE as divested of two fifths of the MAN. "After all, may not another ground be taken on which this article of the Constitution will admit of a still more ready defense? We have hitherto proceeded on the idea that representation related to persons only, and not at all to property. But is it a just idea?

Government is instituted no less for protection of the property, than of the persons, of individuals. The one as well as the other, therefore, may be considered as represented by those who are charged with the government. Upon this principle it is, that in several of the States, and particularly in the State of New York, one branch of the government is intended more especially to be the guardian of property, and is accordingly elected by that part of the society which is most interested in this object of government. In the federal Constitution, this policy does not prevail. The rights of property are committed into the same hands with the personal rights. Some attention ought, therefore, to be paid to property in the choice of those hands. "For another reason, the votes allowed in the federal legislature to the people of each State, ought to bear some proportion to the comparative wealth of the States. States have not, like individuals, an influence over each other, arising from superior advantages of fortune. If the law allows an opulent citizen but a single vote in the choice of his representative, the respect and consequence which he derives from his fortunate situation very frequently guide the votes of others to the objects of his choice; and through this imperceptible channel the rights of property are conveyed into the public representation. A State possesses no such influence over other States. It is not probable that the richest State in the Confederacy will ever influence the choice of a single representative in any other State. Nor will the representatives of the larger and richer States possess any other advantage in the federal legislature, over the representatives of other States, than what may result from their superior number alone. As far, therefore, as their superior wealth and weight may justly entitle them to any advantage, it ought to be secured to them by a superior share of representation. The new Constitution is, in this respect, materially different from the existing Confederation, as well as from that of the United Netherlands, and other similar confederacies. In each of the latter, the efficacy of the federal resolutions depends on the subsequent and voluntary resolutions of the states composing the union. Hence the states, though possessing an equal vote in the public councils, have an unequal influence, corresponding with the unequal importance of these subsequent and voluntary resolutions. Under the proposed Constitution, the federal acts will take effect without the necessary intervention of the individual States. They will depend merely on the majority of votes in the federal legislature, and consequently each vote, whether proceeding from a larger or smaller State, or a State more or less wealthy or powerful, will have an equal weight and efficacy: in the same manner as the votes individually given in a State legislature, by the representatives of unequal counties or other districts, have each a precise equality of value and effect; or if there be any difference in the case, it proceeds from the difference in the personal character of the individual representative, rather than from any regard to the extent of the district from which he comes. "Such is the reasoning which an advocate for the Southern interests might employ on this subject; and although it may appear to be a little strained in some points, yet, on the whole, I must confess that it fully reconciles me to the scale of representation which the convention have established. In one respect, the establishment of a common measure for representation and taxation will have a very salutary effect. As the accuracy of the census to be obtained by the Congress will necessarily depend, in a considerable degree on the disposition, if not on the co-operation, of the States, it is of great importance that the States should feel as little bias as possible, to swell or to reduce the amount of their numbers. Were their share of representation alone to be governed by this rule, they would have an interest in exaggerating their inhabitants. Were the rule to decide their share of taxation alone, a contrary temptation would prevail. By extending the rule to both objects, the States will have opposite interests, which will control and balance each other, and produce the requisite impartiality.

PUBLIUS.

Links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #24: The United States Need a Standing Army—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #27: People Will Get Used to the Federal Government—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #30: A Robust Power of Taxation is Needed to Make a Nation Powerful

The Federalist Papers #35 A: Alexander Hamilton as an Economist

The Federalist Papers #35 B: Alexander Hamilton on Who Can Represent Whom

The Federalist Papers #36: Alexander Hamilton on Regressive Taxation

The Federalist Papers #39: James Madison Downplays How Radical the Proposed Constitution Is

The Federalist Papers #41: James Madison on Tradeoffs—You Can't Have Everything You Want

The Federalist Papers #42: Every Power of the Federal Government Must Be Justified—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #44: Constitutional Limitations on the Powers of the States—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #45: James Madison Predicts a Small Federal Government

The Federalist Papers #48: Legislatures, Too, Can Become Tyrannical—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #49: Constitutional Conventions Should Be Few and Far Between

The Federalist Papers #50: Periodic Commissions to Judge Constitutionality Won't Work

The Federalist Papers #51 A: Checks and Balance, or ‘Who Guards the Guardians?'

How to Get Abundant Affordable Housing

The way to have abundant affordable housing is to have abundant housing. That means making it easy to add residential units. I want to propose a simple, if radical policy that can guarantee abundant affordable housing: state or federal laws requiring mandatory permitting of trailer parks that meet a few basic standards.

There is little worry that trailer parks will spring up in a long-lasting way in totally inappropriate places, because any place land is worth too much, a trailer park operator can’t earn a profit. On the other hand, a trailer park gives a developer a nice threat point to persuade a neighborhood to allow more appropriate (and profitable) high-density housing.

Where land is cheaper—perhaps because of noise, or simply by being further out from the city center, a trailer park might make a lot of sense.

As “Do Trailer Parks and Mobile Homes Have a Future As Affordable Housing?” suggests, there is also no reason a trailer park can’t stay a trailer park but go upscale. The legal definition would be that it would have to be the locational home to manufactured housing—at least in the sense that large pieces were made in a factory. This would give an extra boost to home manufacturing, which is desperately needed. As I discuss in “Why Housing is So Expensive,” construction has shown almost no productivity growth by the usual measures. I suspect a lot of that is because most homes don’t have large pieces made in factories. It is hard to improve production if it doesn’t have some degree of centralization and standardization—or at least modularity. The bigger the percentage of homes that have large manufactured pieces, the faster total factor productivity in housing production will improve.

Note that with a state or federal law requiring mandatory permitting of trailer parks that meet a few basic standards you can get affordable housing in most places without subsidies. It is market rate affordable housing—which should be considered the Holy Grail, while subsidized affordable housing is typically just tokenism. I’d like to suggest one place to put the budgetary savings from not subsidizing housing: instead, subsidize convenient, frequent bus service to any sufficiently large concentration of trailers. This helps make sure that the affordable trailer-park housing will work for people. The residents have to be able to get to their jobs, after all—and those with low income often own unreliable cars or no car. (Note that trailer parks have full-scale house rentals as well as people who own the house and only pay plot rent and home-owner’s association fees.)

Also, nearby current residents shouldn’t have to suffer from an increase in crime when a trailer park is created next door. And those in the trailer parks themselves shouldn’t have to suffer with high crime rates, whether many felonies or many small misdemeanors. If this is a genuine danger, we need to be brutally honest about it—and if a genuine danger, it is a legitimate concern. Thus, in addition to subsidizing good bus service to new trailer parks, I suggest state and federal subsidies for extra police to police the new trailer parks and surrounding areas.

Let me give you a challenge: when you hear someone talking about affordable housing without offering a radical scheme that moves at least 10% toward what I am saying, you can know they aren’t serious about affordable housing beyond tokenism. Let’s get real about affordable housing. It is a huge part of the typical individual’s or families budget. So the poor get much less poor when housing gets cheaper. And the rich or middle class whose property values suffer some because the scarcity value is less—or because now they can’t have as much residential segregation can afford the hit.

By the way, people often talk about “systemic racism” without pointing to what it is actually made of. Barriers to residential construction are a big part of structural racism by perpetuating residential segregation that helps the rich and middle class to not care about the poor because they are out of sight, out of mind, and deprives talented children from poor families of mentors they desperately need. (If the poor living near the rich and sending their kids to the local schools makes the rich hate the poor more, rather than caring about them more, then we have worse problems.)

Honoring Marvin Goodfriend →

Bob King pointed me to this Richmond Fed website honoring Marvin Goodfriend. My post “In Honor of Marvin Goodfriend” is in the same spirit.

A Little Bit of Therapy Goes a Long Way

Link to the abstract shown above

Being Less Controlling by Softening Attachment

image source

As one of the few economists who is also a life coach, I offer free Positive Intelligence training for economists:

How Economists Can Enhance Their Scientific Creativity, Engagement and Impact

Reactions to Miles’s Program For Enhancing Economists’ Scientific Creativity, Engagement and Impact

The first step in that training is taking the saboteur assessment. The saboteur assessment is very quick and very revealing. When I took this assessment, the Hyper-Rational, Hyper-Achiever and Victim saboteurs were no surprise to me. But I learned something from my high score for the Controller saboteur. I am working on being less controlling.

To explain what it means to be controlling or not, Shirzad Chamine, the author of the book Positive Intelligence and the originator of the Positive Intelligence curriculum gives the analogy of vainly trying to control the wind and the waves or alternatively, surfing on whatever winds and waves come along.

Another helpful way of thinking about what the alternatives to being controlling are is to think about attachment. Here I use the word in the sense Buddhist’s use it: attachment is not rolling well with the punches that life lands, living in fear of those punches, or acting in fear. A basic principle of Buddhism is that the root of suffering is attachment.

I find the description of different levels of attachment in Don Miguel Ruiz Jr.’s brief book “The Five Levels of Attachment” useful. This book is billed in its subtitle as “Toltec Wisdom for the Modern Age.” To the extent that it actually reflects ancient Toltec wisdom, there is a convergence between Toltec wisdom and Buddhism.

Here are Don Miguel Ruiz Jr.’s 5 levels of attachment, as he describes them using the example of soccer fandom:

Level One: The Authentic Self

Imagine that you like soccer, and you can go to a game at any stadium in the world. It could be a magnificent stadium or a dirt-filled field. The players could be great or mediocre. You are not rooting for or against a side. It doesn't matter who is playing. As soon as you see a game, you sit, watch, and enjoy it for those ninety minutes. You simply enjoy watching the game for what it is. The players could even be kicking around a tin can, and you still enjoy the ups and downs of the sport! The moment the referee blows the whistle that ends the game—win or lose—you leave the game behind. You walk out of the stadium and continue on with your life. …

Level Two: Preference

This time, you attend a game—again, at any stadium in the world, with any teams playing—but now you root for one of the teams. … You created a story of victory or defeat that shaped the experience, but the story had nothing to do with you personally, because the story was about the team. You engaged with the event and the people around you, but at the end of the game, you simply say, “That was fun,” and let go of the attachment. …

Level Three: Identity

This time, you are a committed fan of a particular team. Their colors strike an emotional chord inside of you. When the referee blows the whistle, the result of the game affects you on an emotional level. … You feel elated when your team wins; when your team loses, you feel disappointed. But still, your team's performance is not a condition of your own self-acceptance. And if your team loses, you're able to accept the defeat as you congratulate the other side. … if your team loses, you might have a bad day at work, argue with someone about what or who is responsible for the team losing, or feel sad despite the good things going on around you. No matter what the effect is, you've let an attachment change your persona. Your attachment bleeds into a world that has nothing to do with it.

Level Four: Internalization

… at Level Four your association with your favorite team has now become an intrinsic part of your identity. The story of victory and defeat is now about you. Your team's performance affects your self-worth. When reading the stats, you admonish players for making us look bad. If the opponent team wins, you get angry that they beat you. You feel disconsolate when your team loses, and may even create excuses for the defeat. Of course you would never sit down with one of their fans in a pub for a friendly chat! …

Level Five: Fanaticism

At this level, you worship your team! Your blood bleeds their colors! If you see an opposing team's fan, they are automatically your enemy, because this shield must be defended! This is your land, and others must be subjugated so that they, too, can see that your team is the real team; others are just frauds. What happens on the field says everything about you. Winning championships makes you a better person, and there is always a conspiracy theory that allows you to never accept a loss as legitimate. There is no longer a separation between you and your attachment of any kind. You are a committed to your team through and through, a fan 365 days a year. Your family is going to wear the jersey, and they better be fans of your team. If any of your kids become a fan of an opposing team, you will disinherit them. … at Level Five you don't waste your time with people who don't love the sport.

The real power in this idea of attachment is in applying it to areas of life far beyond sports. Here are some areas in which I notice a lot of attachment by people I know (a set that includes me):

political party

particular political issues such as climate change or animal rights

academic discipline

field within economics

style of research within a field in economics

having particular technical skills

having particular social and organizational skills

There is a subtle distinction to be made between devoting oneself to a project or a cause and becoming attached to it. One can devote oneself to a cause and do one’s utmost to advance that cause without your heart being occupied with anger at those who don’t see the importance of that cause or even work against it and without your heart being occupied by the bad things that might happen that are completely beyond your control.

To use a military analogy, Napoleon kept some of his forces in reserve to send into battle at the crucial place a the crucial moment. If all of his forces were in the thick of the fight from the beginning—attached to a particular part of the battle already, with little ability to extricate themselves—he couldn’t have taken advantage of opportunities that arose.

Decision of how long to persist in a particular direction of action and when to do a course correction are crucial in life. Attachment interferes with making those decisions well. You might be too attached to a particular course of action that you persist to long or you might be so attached to winning that you quit too soon when the chance of failure gets to the same order of magnitude as the chance of success.

The more you spy out excesses of attachment and notice the temptations you face to try to control things beyond what is gracefully possible, the more calm and effective you will be. People differ in how big a problem attachment and being controlling is in their lives, but this is an issue at some level for almost everyone.

Posts on Positive Mental Health and Maintaining One’s Moral Compass:

Co-Active Coaching as a Tool for Maximizing Utility—Getting Where You Want in Life

How Economists Can Enhance Their Scientific Creativity, Engagement and Impact

Judson Brewer, Elizabeth Bernstein and Mitchell Kaplan on Finding Inner Calm

The World Isn't Fair. Any Fairness You Stumble Across Is There Because Someone Put It There.

Sometimes the Devil You Don't Know is Better than the Devil You Do

Zen Koan Practice with Miles Kimball: 'I Don't Know What All This Is'

Recognizing Opportunity: The Case of the Golden Raspberries—Taryn Laakso

Taryn Laakso: Battery Charge Trending to 0% — Time to Recharge

Savannah Taylor: Lessons of the Labyrinth and Tapping Into Your Inner Wisdom

On the DSM (Clinical Psychology's 'Diagnostic Statistical Manual')

In the talk shown above about the nature of clinical psychology, Jordan Peterson spends most of his time persuasively making the case that values are an unavoidably central part of clinical psychology. That is very useful.

But I want to focus on the beginning of the talk, about how psychological diagnostic categories are “family resemblance” categories, in Wittgenstein’s terms. Jordan gives the example of a category with a list of 10 symptoms, any 5 of which suffice to declare someone to have that disorder. That means two people could share no symptoms and be diagnosed as having the same disorder.

Let me try top clear up the issues conceptually. What is fundamentally at issue is the efficacy (good effects minus bad side effects) of various types of treatment. Although enough data may not be available to do this for real, conceptually this is a matter of regressing the efficacy of a particular treatment (let’s say by a randomized trial) on a list of symptoms and other indicators. Labeling something as a particular syndrome could mean at least two different things (or could simply be incoherent). It could mean that a set of symptoms strongly co-move so that there seems to be a strong factor in the factor-analytic sense. In that case, taking an average over many symptoms (which amounts to counting if one is only assessing symptoms at the 0 or 1 level of discrimination) makes sense. The other thing labeling something as a syndrome could mean is that there are significant interaction terms in the regression, so that two or more symptoms co-occurring is more predictive than just the sum of the symptoms would predict.

The bottom-line is that if one can specify what they are for (in this case, guiding treatment), family resemblance categories can be thought of in terms of a regression with the individual characteristics as regressors.

In Praise of Buckwheat Pillows

For many years, my wife Gail and I have happily used buckwheat pillows. We had a chiropractor in Ann Arbor who got us into them. The great thing about buckwheat pillows is that you can squish around the buckwheat inside so that they perfectly support your neck will leaving your head in full alignment with your spine.

The buckwheat pillow above is small enough to easily take on trips, while being big enough for comfortable use at home as well. (It comes with a travel case.)

When you first get a buckwheat pillow, it’s a good idea to remove several cups of the buckwheat and put them in ziplock bags. You can always add it back if the pillow feels like it needs it.

What we love about buckwheat pillows is:

Fewer headaches caused by a sore neck!

As mentioned above, you can rearrange the buckwheat to provide support only for your neck. (You can have your head nearly flat on the mattress after you rearrange the buckwheat). You can change the arrangement (don’t worry, you get really fast at this and it comes naturally) when you are ready to roll on your side or onto your back.

Buckwheat pillows stays cooler than regular pillows.

When Gail and I were part of a wildfire evacuation a few months ago (see “New Year's Gratitude on the Occasion of the Marshall Fire”), Gail remembered to bring her buckwheat pillow. I forgot. I regretted that. I could feel the difference in my neck after just a few days without.

Acknowledgement: Gail contributed to this post.