Alice Han and Chris Miller: Political Economy Roots of China's Debt Problem

Alice Han and Chris Miller's July 7, 2017 Wall Street Journal article "China's Awkward Debt Problem" is the best article I have ever seen about China's political economy in recent years. I highly recommend you read the entire article, but let me give a few teasers:

China has long relied on debt to fuel growth. The country’s debt burden expanded over 2.5 times faster than its economy in 2016, and its ratio of corporate debt to GDP is one of the highest ever seen in a big economy. ...

Why can’t China kick its debt addiction? The obstacles are political, not economic. Local governments and bosses of state-owned enterprises benefit immensely from government-subsidized loans, and these groups form the backbone of the Chinese Communist Party. ...

The most powerful business interests within the party are those that benefit most from cheap, state-funded lending, fueling China’s debt bubble. The bosses of state-owned firms are in theory subordinate to the party hierarchy. In reality, they constitute a powerful lobby, demanding cheap loans from state banks and the ability to use public assets for the private interests of the monopolies they run. ...

Provincial and local government officials are even more powerful than the bosses of state-owned firms. Real-estate development—which is no less reliant on cheap credit—has driven growth in many regions. It is also a lucrative source of corruption, as local officials sell off property to developers on the cheap in exchange for kickbacks. ...

Believe in Yourself

Link to the Youtube audio above

Link to the full lyrics of "A Rose is a Rose"

Very few of us, no matter how self-assured we may seem, escape periods of self-doubt. Mine came in the late 1990's. After much good fortune early in my career, around that time I had several National Science Foundation grant proposals rejected, one after another. One line of my thinking took me to resentment and anger at an economics profession that didn't appreciate the merit of my work. But another, insistent line of thinking took me to self doubt. In particular, I wondered if maybe I wasn't as good as I had thought I was. Maybe the anonymous reviewers who had rejected my proposals had it right in something they hadn't actually said outright, but seemed to be saying between the lines: maybe I was a mediocre economist. My brain looped over and over again between these two alternatives. Neither alternative was a pleasant one, but wondering if I was mediocre after all was the worst.

It might make a better story if I could say that I got out of this loop by myself, but I didn't. I had done some psychotherapy before, focusing in classic fashion on understanding my relationship with my Mother, and to a lesser extent, my Dad. Having felt some closure there, I had ended that round of therapy. Now I returned to therapy to figure out how to deal with these distressing career thoughts.

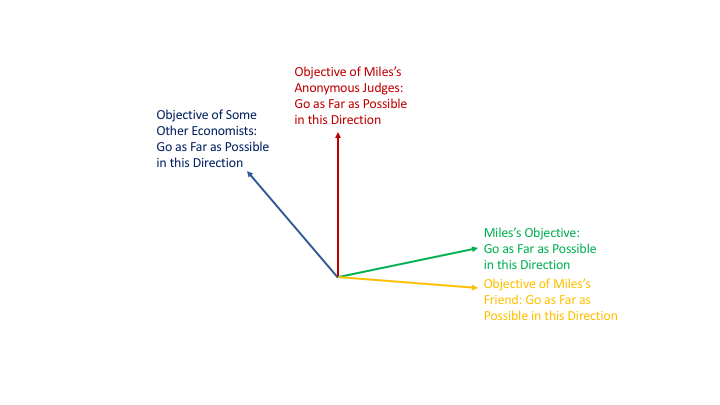

Very laboriously, and with much help, I did reach some degree of resolution. What brought me a degree of inner peace was an insight I have always pictured in terms of arrows representing the directions different economists want to go scientifically. Technically, these arrows are the gradient vectors of various people's objective functions for their scientific work.

I realized that I had been treating the anonymous judges of my National Science Foundation grant proposals as if they were God. And I had been assuming the standards by which they judged good work were the same as my own standards for good work. But in fact, their ideas of what constituted good work were very different from mine. What they thought an economist should be trying to do, was different than what I thought I should be trying to do. I really was trying hard to live up to my own scientific ideals, but my ideals were not the same as theirs. In a way beyond my fathoming, other economists had different values than I did. Some had scientific objectives close enough to mine that they felt I was largely going in the right direction. Others had scientific objectives far enough from mine they thought I was going in the wrong direction. The anonymous judges of my National Science Foundation grant thought I was going partly in the right direction, far enough to say a few positive words, but that I was also going off track in serious ways. No one thought I was doing nothing, though some thought a large share of my scientific activities were a waste.

I still think about these issues often. But instead of going back and forth between feeling unappreciated and doubting myself, now I go back and forth between thinking others should come more in my direction and thinking there are a wide variety of legitimate viewpoints, even if I find some of those viewpoints quite alien. That brain loop is not so bad even when I do get into it. And I find it easier to get out of that loop.

One thing that helps me now when I see others getting honors or rewards I wish I were getting is to remember what I have set as my own goals and think of how those goals are likely to be different than the goals of those who got those honors and rewards. (I think there are many other academics more subject to envy than I am, but I am very far from immune to envy!) It helps that I have some of those goals written down, most recently in the post I wrote for the 5th anniversary of this blog: "My Objective Function."

For me, one other thing that has helped me in times of envy and self doubt has been listening to the song in the Youtube audio at the top of this post: "A Rose is a Rose" from Susan Ashton's self-titled 1993 album "Susan Ashton." Let me give a commentary on the lyrics to point out how this song illustrates the principles above. These lyrics are by Wayne Kirkpatrick.

The song begins

You're at a stand still, you're at an impasse

Your mountains of dreams, seems harder to climb

By those who have made you feel like an outcast

Cause you dare to be different, so they're drawing a line

The words "you dare to be different, so they're drawing a line" are perfect for describing the difference in gradient vectors I have drawn above!

Next,

They say you're a fool, they feed you resistance

They tell you you'll never go very far

Notice that when the naysayers say "you'll never go very far," they are only counting your progress in their preferred direction. They aren't counting all the progress you are making toward what you think is important, but they don't.

The following two lines are some of my favorites. They operate on an emotional, fantasy level:

But they'll be the same ones that stand in the distance

Alone in the shadow of your shining star

It is not at all clear that such a moment of vindication will ever come, but just imagining it makes me feel better. People seldom admit they are wrong, and it is unwise to count on one's tormentors ever doing so. But what we can do is provide these moments of vindication for our friends and loved ones. One of the things my wife Gail and I do to keep our marriage strong is to say often to one another "You were right and I was wrong." You would be surprised at what a strong bond this creates, because you can't get that from just anyone!

Next, the refrain gives the key practical advice—don't overreact to criticism by changing your direction too much:

Just keep on the same road and keep on your toes

And just keep your heart steady as she goes

And let them call you what they will

It don't matter, a rose by any name is still a rose

It is worth thinking about criticism. It is worth making course corrections if you are genuinely convinced by something someone says. But unless you think there is some chance that what you have been doing is genuinely destructive, keeping on keeping on in mostly the same direction may be the course of action that is truest to your own values. (Of course, if you have been going contrary to your own values, you should rethink what you are doing and change course immediately.)

Next, the lyrics move to encouragement:

The kindness of strangers, it seems like a fable

But they've yet to see what I see in you

Friends are valuable advisors, both because they are more likely to share some of your sense of what is most important and because they know things about you and your life that others don't. It is important to distinguish between criticism or praise from enemies, criticism or praise from strangers, and criticism or praise from friends.

What I think is the heart of the lyrics are these two lines:

But you can make it if you are able

To believe in yourself the way I do

Notice that "believe in yourself the way I do" means "believe in yourself the way I, your friend, believe in you." It is hard to overstate the importance of believing in yourself. This is the theme of my post "The Unavoidability of Faith." Believing that by your efforts, you can make things better is the first step toward living a life that you love and saving the world.

After the second time through the refrain comes a reinforcement of the point that criticism does not change the facts of who you are. It may occasionally reveal something you hadn't realized before. But if you can view criticism with dispassion, it never makes you worse than you were before you heard the criticism:

'Cause a deal is a deal in the heart of the dream

And a spade is a spade, if you know what I mean

And a rose is a rose is a rose

Roland Benabou has a fascinating line of research (some of it with coauthors) in which people are modeled as trying to manipulate what information they have in order to feel better about themselves. I discussed these ideas in depth with Roland when the two of us went to dinner after a seminar I gave at the Economics Department at Princeton. I remember being both (a) being persuaded that this was a plausible account of how people actually behave and (b) thinking that such behavior is deeply irrational. More pointedly, I realized that (a) I do this and (b) even if there is any way that it could be a good idea for anyone to do this, it makes no sense at all for me to do it.

Born in 1960, I have already had many decades worth of evidence about my own characteristics. As long as I can avoid the kinds of extreme situation seen in movies, a single day's or a single week's worth of additional evidence about myself should not change that picture much. The biggest likely piece of information about myself would be to learn something that had been true for a long time that I had somehow managed not to see. That might sting, but at least I could console myself that others around me had probably seen that all along and some of them had stayed my friends anyway!

Even when it comes to criticism that I should really listen to in order to make a significant course correction in my life, I have learned the importance of what my therapist (a later one) called "titrating" the criticism: letting it in a little at a time, so I don't go down a psychological rabbit hole.

As for less helpful criticism, Wayne Kirkpatrick's lyrics say this:

To deal with the scoffers it's part of the bargain

They heckle from back rows and they bark at the moon

The goals and objectives that each person cultivates can be seen as a garden. Wayne's next line may or may not be true of your enemies' efforts:

Their flowers are fading in time's bitter garden

But ....

But if you believe in yourself and work hard, the next line—the last line before the final refrain—is true of your own garden:

... yours is only beginning to bloom

Nick Rowe: Equalizing the Twin Markups in a Monopolistically Competitive Macroeconomy →

This is Nick Rowe's reaction to my post "Returns to Scale and Imperfect Competition in Market Equilibrium" (which in turn builds on my post "There Is No Such Thing as Decreasing Returns to Scale").

Salt Is Not the Nutritional Evil It Is Made Out to Be

This post could just as well have been titled "Sugar, Not Salt, Should Be the Primary Suspect for Causing High Blood Pressure." The basic argument is that the effects of salt on blood pressure are quite small, while blood pressure has a strong association with insulin and insulin resistance, which in turn are strongly associated with eating refined carbohydrates such as sugar that spike insulin. To make this case, I will turn primarily to excerpting some of what Gary Taubes says in his excellent history of thought about nutrition Good Calories, Bad Calories, which chronicles a great deal of dogmatic arrogance by influential nutrition scientists who outshouted the ideas of other nutrition scientists who had just as much evidence on their side. This claim about dogmatic arrogance can be easily (if laboriously) documented from the historical record, as Gary Taubes does.

The quotations below are from Chapter 8: "The Science of the Carbohydrate Hypothesis."

First, Gary Taubes makes the case that high blood pressure is associated with the pre-diabetes condition of insulin resistance, which is also called metabolic syndrome:

Hypertension is defined technically as a systolic blood pressure higher than 140 and a diastolic blood pressure higher than 90. It has been known since the 1920s, when physicians first started measuring blood pressure regularly in their patients, that hypertension is a major risk factor for both heart disease and stroke. It’s also a risk factor for obesity and diabetes, and the other way around—if we’re diabetic and/or obese, we’re more likely to have hypertension. If we’re hypertensive, we’re more likely to become diabetic and/or obese. For those who become diabetic, hypertension is said to account for up to 85 percent of the considerably increased risk of heart disease. Studies have also demonstrated that insulin levels are abnormally elevated in hypertensives, and so hypertension, with or without obesity and/or diabetes, is now commonly referred to as an “insulin-resistant state.” (This is the implication of including hypertension among the cluster of abnormalities that constitute metabolic syndrome.) Hypertension is so common in the obese, and obesity so common among hypertensives, that textbooks will often speculate that it’s overweight that causes hypertension to begin with. So, the higher the blood pressure, the higher the cholesterol and triglyceride levels, the greater the body weight, and the greater the risk of diabetes and heart disease.

Next, Gary discusses the weakness of the evidence for any serious harm from salt. In particular, even cutting salt in half would reduce blood pressure by only 4 or 5 points ("millimeters of mercury"), while even mildly high blood pressure is 20 points higher than normal, and serious high blood pressure is 40 points higher than normal.

Despite the intimate association of these diseases, public-health authorities for the past thirty years have insisted that salt is the dietary cause of hypertension and the increase in blood pressure that accompanies aging. Textbooks recommend salt reduction as the best way for diabetics to reduce or prevent hypertension, along with losing weight and exercising. This salt-hypertension hypothesis is nearly a century old. It is based on what medical investigators call biological plausibility—it makes sense and so seems obvious. When we consume salt—i.e., sodium chloride—our bodies maintain the concentration of sodium in our blood by retaining more water along with it. The kidneys should then respond to the excess by excreting salt into the urine, thus relieving both excess salt and water simultaneously. Still, in most individuals, a salt binge will result in a slight increase in blood pressure from the swelling of this water retention, and so it has always been easy to imagine that this rise could become chronic over time with continued consumption of a salt-rich diet.

That’s the hypothesis. But in fact it has always been remarkably difficult to generate any reasonably unambiguous evidence that it’s correct. In 1967, Jeremiah Stamler described the evidence in support of the salt-hypertension connection as “inconclusive and contradictory.” He still called it “inconsistent and contradictory” sixteen years later, when he described his failure in an NIH-funded trial to confirm the hypothesis that salt consumption raises blood pressure in school-age children. The NIH has funded subsequent studies, but little progress has been made. The message conveyed to the public, nonetheless, is that salt is a nutritional evil—“the deadly white powder,” as Michael Jacobson of the Center for Science in the Public Interest called it in 1978. Systematic reviews of the evidence, whether published by those who believe that salt is responsible for hypertension or by those who don’t, have inevitably concluded that significant reductions in salt consumption—cutting our average salt intake in half, for instance, which is difficult to accomplish in the real world—will drop blood pressure by perhaps 4 to 5 mm Hg in hypertensives and 2 mm Hg in the rest of us. If we have hypertension, however, even if just stage 1, which is the less severe form of the condition, it means our systolic blood pressure is already elevated at least 20 mm Hg over what’s considered healthy. If we have stage 2 hypertension, our blood pressure is elevated by at least 40 mm Hg over healthy levels. So cutting our salt intake in half and decreasing our systolic blood pressure by 4 to 5 mm Hg makes little difference.

Salt may cause some water retention, but perhaps surprisingly, so do sugar and other carbohydrates:

The laboratory evidence that carbohydrate-rich diets can cause the body to retain water and so raise blood pressure, just as salt consumption is supposed to do, dates back well over a century. It has been attributed first to the German chemist Carl von Voit in 1860. In 1919, Francis Benedict, director of the Nutrition Laboratory of the Carnegie Institute of Washington, described it this way: “With diets predominantly carbohydrate there is a strong tendency for the body to retain water, while with diets predominantly fat there is a distinct tendency for the body to lose water.” ...

The “remarkable sodium and water retaining effect of concentrated carbohydrate food,” as the University of Wisconsin endocrinologist Edward Gordon called it, was then explained physiologically in the mid-1960s by Walter Bloom, who was studying fasting as an obesity treatment at Atlanta’s Piedmont Hospital, where he was director of research. As Bloom reported in the Archives of Internal Medicine and The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the water lost on carbohydrate-restricted diets is caused by a reversal of the sodium retention that takes place routinely when we eat carbohydrates. Eating carbohydrates prompts the kidneys to hold on to salt, rather than excrete it. The body then retains extra water to keep the sodium concentration of the blood constant. So, rather than having water retention caused by taking in more sodium, which is what theoretically happens when we eat more salt, carbohydrates cause us to retain water by inhibiting the excretion of the sodium that is already there. Removing carbohydrates from the diet works, in effect, just like the antihypertensive drugs known as diuretics, which cause the kidneys to excrete sodium, and water along with it.

The reduction of bloating when someone goes on a low-carb diet is so substantial that weight loss in the first week or two can be quite dramatic, because this water loss is added to whatever fat loss there is.

In the progression above, I skipped over Gary's discussion of how high blood pressure is one of the "Diseases of Civilization," later renamed more politically correctly as "Western Diseases." That is, people from non-European cultures who eat traditional diets have very little high blood pressure, just as they have very little obesity, very little heart disease and very little cancer. This is true for a wide range of different traditional diets, including the fatty-red-meat-laden traditional Inuit diet, the traditional Masai diet of milk, meat and blood, and diet of coconuts and fish (later coconuts, fish and breadfruit) on the Pacific island of Tokelau. Thus, high blood pressure seems most likely to be due to non-traditional foods, such as sugar, white flour and other highly refined carbohydrates. More generally, it seems likely to be something to which advanced European food-processing technology contributed that was the culprit. When any group began eating distinctively Western foods—of which processed foods are the most distinctive—something in that menu seems to have led to a wide range of chronic diseases.

Gary does not say this, but salt in particular does not seem to be a good candidate as a cause for one of the "Western Diseases" since it would be quite surprising if there were not some traditional diets that were heavy on salt—perhaps because of a location near the sea—that would have revealed clearly any strong association of salt with high blood pressure.

Finally, given the importance of sugar and other refined carbohydrates in causing insulin spikes, the following passages about insulin are damning for sugar and refined carbohydrates more generally:

Finally, by the mid-1990s, diabetes textbooks, such as Joslin’s Diabetes Mellitus, contemplated the likelihood that chronically elevated levels of insulin were “the major pathogenetic defect initiating the hypertensive process” in patients with Type 2 diabetes. But such speculations rarely extended to the potential implications for the nondiabetic public. ...

Since the late 1970s, investigators have demonstrated the existence of other hormonal mechanisms by which insulin raises blood pressure—in particular, by stimulating the nervous system and the same flight-or-fight response incited by adrenaline.

Update: Mark Fontana points me to Gina Kolata's May 8, 2017 New York Times article "Why Everything We Know About Salt May Be Wrong," which complicates the story further. What is clear is that the traditional story about salt is wrong and there is no adequate reason to worry about salt intake in the normal range because there simply isn't enough science to justify worry (unless you like worrying). Gina Kolata's article is also interesting one of her interviewees illustrates the way in which many in the nutritional establishment continue to assert the same thing they didn't have enough evidence for in the first place in the face of further contradictory evidence:

“The work suggests that we really do not understand the effect of sodium chloride on the body,” said Dr. Hoenig.

“These effects may be far more complex and far-reaching than the relatively simple laws that dictate movement of fluid, based on pressures and particles.”

She and others have not abandoned their conviction that high-salt diets can raise blood pressure in some people.

But now, Dr. Hoenig said, “I suspect that when it comes to the adverse effects of high sodium intake, we are right for all the wrong reasons.”

On what basis does Dr. Hoenig say “I suspect that when it comes to the adverse effects of high sodium intake, we are right for all the wrong reasons,” other than out of sheer stubbornness?

Don’t miss my other posts on diet and health. I should note that my views of Gary Taubes have evolved. I have an entire section below of links to posts about Gary Taubes and his work.

I. The Basics

Jason Fung's Single Best Weight Loss Tip: Don't Eat All the Time

What Steven Gundry's Book 'The Plant Paradox' Adds to the Principles of a Low-Insulin-Index Diet

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

How Fasting Can Starve Cancer Cells, While Leaving Normal Cells Unharmed

Meat Is Amazingly Nutritious—But Is It Amazingly Nutritious for Cancer Cells, Too?

IV. Eating Tips

Using the Glycemic Index as a Supplement to the Insulin Index

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Wonkish

Anthony Komaroff: The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes

Carola Binder: The Obesity Code and Economists as General Practitioners

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

Jason Fung: Dietary Fat is Innocent of the Charges Leveled Against It

Faye Flam: The Taboo on Dietary Fat is Grounded More in Puritanism than Science

Confirmation Bias in the Interpretation of New Evidence on Salt

Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina: Why You'll Be Disappointed If You Are Exercising to Lose Weight, Explained with 60+ Studies (my retitling of the article this links to)

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

Putting the Perspective from Jason Fung's "The Obesity Code" into Practice

'Forget Calorie Counting. It's the Insulin Index, Stupid' in a Few Tweets

Debating 'Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid'

Analogies Between Economic Models and the Biology of Obesity

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.

Contra Randal Quarles

Donald Trump has nominated Randal Quarles as the Federal Reserve's Vice Chairman for Supervision. This is a position that really matters. As Ryan Tracy wrote in the July 28, 2017 Wall Street Journal article "Meet Randal Quarles, Trump’s Pick to Shake Up the Fed,"

Mr. Quarles, who would be President Donald Trump’s first appointee to the central bank, is expected to be confirmed in coming months for a four-year term as Fed vice chairman for supervision. That would make him the most influential U.S. financial regulator and give him a voice on monetary policy.

I urge the Senate not to confirm him.

If Randal does become the Federal Reserve's Vice Chairman for Supervison, I hope that Randal changes his views (or perhaps has already changed his views since the quotations below). Let me detail where I disagree with Randal to do my bit toward one of those more favorable outcomes. I will mostly follow the order of the article linked above: "Fed Nominee Randal Quarles in His Own Words." Most of the quotations below from Randal can be found in that article; some are in sources that article links to.

How Should Banks Be Funded?

Randal the 2016 op-ed "Focusing on Bank Size, Missing the Real Problem" with Lawrence Goodman. They write:

Focusing on bank size is politically appealing but diverts attention from the major source of systemic risk in the financial sector: a shortage of stable deposits. Banks are but one part of an interconnected financial sector providing over $40 trillion of credit to the economy, but that credit is supported by only about $11 trillion of bank deposits.

The gap must be closed largely with professionally managed, “wholesale” funding, such as short-term repurchase agreements. Wholesale funders are quick to pull their support by not rolling over short-term credit if they perceive those funds are at risk. This leads to periodic runs on financial institutions and the resulting demand for government intervention to prevent the failure of those institutions.

It is fair to say that "too big to fail" has been overhyped, since "too many to fail" can also lead to bailouts. And Randal and Lawrence are right that the way in which banks are funded is the key question for financial stability. But after saying correctly that the way banks are funded now is unsafe, without even trying to offer a better means of funding banks, they dismiss what they concede would be a much safer means of funding banks:

Mr. Kashkari’s alternative proposal, promoted by academics including most vocally Stanford economist Anat Admati, is to ramp up bank capital to such a degree that the possibility of failure would be remote to nonexistent. But the consequence of a dramatic increase in bank capital is an increase in the cost of bank credit, meaning higher interest rates across the board. Those who favor much higher bank capital argue this would not happen, because investors would accept lower returns if the banks they put their money in were safer.

In the real world of capital markets, however, there are not enough natural investors in bank equity seeking utility-like returns.

Note that Randal and Lawrence do not dispute that increasing bank capital would make banks safer. They concede that point. They object because they believe making banks safer in this way will increase the cost of bank credit so much that it outweighs the benefit of the extra safety.

Let me argue that the increase in the cost of bank credit would not be so great or so harmful as Randal and Lawrence believe. First, I think they are wrong when they say

... there are not enough natural investors in bank equity seeking utility-like returns.

If bank stock really were as safe as utilities, the same kind of people who invest in utilities and who invest in corporate bonds would invest in safe bank stock. The issue is that bank stock has to prove over time that it is, indeed, safe. Theory gives excellent reason to think that, other things equal, bank stock will be much safer when there is more of it for a bank of given size, since the risk will be shared across more stockholders. But one should not expect investors to instantly believe bank stock is safer than it used to be, especially so soon after a painful financial crisis. And so far the increase in the risk spreading by an increase in the total amount of stock has been modest enough that other factors could easily overwhelm the effects of greater equity finance. So the push towards banks being financed by stock instead of by "wholesale funding" needs to be sustained for long enough to make bank stock so much safer that investors can't help but see the added safety.

Second, of course the cost of bank credit would go up if banks were required to finance themselves more from stock rather than flightier funding ("more bank capital"). But that is as it should be. Because banks would be safer, they would lose the implicit bailout subsidy they now have. Without that government subsidy to lending, it is natural and appropriate for the cost of lending to go up. If we think that the government should be subsidizing lending (say to counteract a distortionary financial friction), let's at least subsidize lending in a way where banks don't have the incentive to design themselves as fragile in order to get the subsidy.

The bankruptcy of Randal and Lawrence's approach becomes clear in this passage from their op-op-ed:

Given these structural facts, the job of the regulatory system is clear. First, facilitate the reallocation of capital during the inevitable periodic crises through orderly liquidation of failing or failed banks.

That is, "Give up on trying to keep banks from failing. Give up on trying to have the cost of mistakes absorbed by stockholders. Depend on "orderly liquidation" to happen fast enough to keep a financial crisis from getting worse. This is not a plan for avoiding financial crises at all, it is a resignation to the fate of serious financial crises over and over again. If banks make bad bets, the one truly "orderly" way to have the system of losses is to have enough stockholders who have

- signed up to take the hit if things to south,

- in that worst case scenario take the hit very quickly, before they have had a chance to build up steam to ask for a bailout, and

- are reminded every day as the stock prices go up and down that they have accepted that risk, so that they have a hard time pretending they didn't know, and should be bailed out.

The Role of the Government in the Financial System

In a May 2015 Bloomberg television interview, Randal said

“The government should not be a player in the financial sector. It should be a referee. And both the practice and the policy and the legislation that resulted from the financial crisis tended to make the government a player. It put it on the field as opposed to simply reffing the game.”

The government is a player in the financial system as long as banks think they will be bailed out in in a crisis. In order to be less of a player through expected bailouts, the government has outlaw the kind of designed fragility that banks have the incentive to pursue given the bailout subsidy. To me, insisting on very high capital requirements is acting like a referee, since the whole game comes crashing down when bank mistakes cannot be absorbed by stockholders. But this is a type of getting out of the game and being a referee that Randal argued against.

One key way in which high equity requirements allow the government to get out of the game and be a referee is that if liability-side regulation for banks means that stockholders are set to absorb losses, the government doesn't need heavy-handed legislation on the asset side. For example, the Volcker rule that Randal said in the same Bloomberg TV interview he dislikes is only needed because capital requirements are too low. (See my post "The Volcker Rule.")

Of course, some asset-side regulations are necessary, because extreme-enough derivatives on the asset-side could create a situation equivalent to excessive leverage, even if a very large share of funding came from equity. But with a very high equity requirement on the liability side of banks' balance sheets, the asset-side rules would only need to rule out practices that are quite far from what most banks currently do on the asset side.

There are other ways of getting out of the game and being a more neutral referee that I think Randal and I might agree on. Let's split up Fannie and Freddie and fully privatize the pieces. Let's equalize the taxation of debt and equity so that incentive towards high leverage isn't added on top of the bailout subsidy.

On Monetary Rules

Here I can just use duelling quotations. From the May 2015 Bloomberg TV interview:

Randal: I am all for transparency; I think the Fed has that part of it right. What it has wrong is that it continues to believe that it shouldn’t be following a rule. If you are going to be transparent in activity like the Fed’s, you have to be much more rule-based in what you are doing. The transparency has to involve, ‘This is the rule that we will follow.’ So that the markets can say, “OK, we now understand what is the Fed is going to do. We can see what its inputs are.”

From my paper "Next Generation Monetary Policy" (see "The Scientific Approach to Monetary Rules"):

Because optimal monetary policy is still a work in progress, legislation that tied monetary policy to a specific rule would be a bad idea. But legislation requiring a central bank to choose some rule and to explain actions that deviate from that rule could be useful. To be precise, being required to choose a rule and explain deviations from it would be very helpful if the central bank did not hesitate to depart from the rule. In such an approach, the emphasis is on the central bank explaining its actions. The point is not to directly constrain policy, but to force the central bank to approach monetary policy scientifically by noticing when it is departing from the rule it set itself and why.

Interest Rates and Speculation, Hawks and Doves

In "Focusing on Bank Size, Missing the Real Problem," Randal and his coauthor Lawrence write:

Years of near-zero interest rates have led to a rise in speculative positions across a wide range of asset classes, as all financial institutions find themselves under intense pressure to seek adequate returns.

Let me answer this in a roundabout way. At the Mercatus Center's "Monetary Rules for a Post-Crisis World" Conference" (video) where I first presented "Next Generation Monetary Policy," I made the point that being a monetary "hawk" or dove makes little sense if a "hawk" is someone who, whatever the circumstance, thinks interest rates should be higher and a "dove" is someone who, whatever the circumstance, thinks interest rates should be lower. In my view, as laid out in "Next Generation Monetary Policy," interest rates should be very high for brief periods in some circumstances and very low for brief periods in others, in order to quickly right the economy if it lists towards overheating or recession. The way to tell someone who is a hawk is the tendency to set out a motley grab bag of arguments that have no coherence except that they all favor higher interest rates. Despite his stated views in favor of monetary rules that have interest rates much higher in some circumstances than others, John Taylor is a good source for such a motley grab back of arguments. You can see this motley grab bag in my post "Contra John Taylor." The argument that low interest rates lead to excessive speculation is a particular favorite of hawks. Here is what John said together with my reply:

[John Taylor:] The Fed’s current zero interest-rate policy also creates incentives for otherwise risk-averse investors—retirees, pension funds—to take on questionable investments as they search for higher yields in an attempt to bolster their minuscule interest income.

[Miles:] I can’t make sense of this statement without interpreting it as a behavioral economics statement about some combination of investor ignorance and irrationality and fraudulent schemes that prey on that ignorance and irrationality. The often-repeated claim that low interest rates lead to speculation cries out for formal modeling. I don’t see how such a model can work without some combination of investor ignorance and irrationality and fraudulent schemes preying on that ignorance and irrationality. (That is, I don’t see how the claim could hold in a model with rational agents and no fraud.) Whatever combination of investor ignorance and irrationality and fraudulent schemes preying on that ignorance an irrationality a successful model uses are likely to have much more powerful implications for financial regulation than for monetary policy. It is cherry-picking to point to implications of a not-fully-specified model for monetary policy and ignore the implications of that not-fully-specified model for financial regulation.

To what I said back in January 2013, I should add two thoughts, in response to both John and Randal's concerns about what is often called "reaching for yield."

First, it is possible to have an "irrational firm" due to incentive structures within the firm, or an "irrational contract" due to incentive structures within the contract, even if given the structure of the firm or contract the individuals act rationally. This is sometimes called an "institutional" explanation of a phenomenon.

Second, remember that "risk-taking" has a positive side to it. Often, a recession persists because of too little risk-taking. When people aren't taking the risks the economy needs them to take to keep functioning well, it is important to make the alternative of playing it safe less attractive. That is exactly what low interest rates do.

The key to making risk-taking a good thing rather than a bad thing is to align the benefits and costs of the risk to the one making the risk-taking decision with the benefits and cost of the risk to society. Having high enough levels of equity—or equivalently, low enough leverage—so that there won't be bailouts helps a lot with that alignment. Otherwise it is "heads I win, tails the taxpayer loses."

In "Monetary Policy and Financial Stability" I argue:

- It is almost impossible for monetary policy to stimulate the economy except by (a) raising asset prices, (b) causing loans to be made to borrowers who were previously seen as too risky, or (c ) stealing aggregate demand from other countries by causing changes in the exchange rate.

- Quantitative easing is likely to have unprecedented effects on financial markets—effects that will look unfamiliar to those used to what the standard monetary policy tool of cutting short-term interest rates does.

- It is not risk-taking we should be worried about, but efforts to impose risks on others—including taxpayers—without fully paying for that privilege.

... nonstandard monetary policy in the form of purchases of long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities and “forward guidance” on future short-term interest rates take the economy into uncharted territory. But uncharted territory brings not only the possibility of new monsters but also the near certainty of previously unseen creatures that might look like monsters, but are harmless.

Letting people get high interest rates from a central bank is OK when they would otherwise invest too much and overheat the economy. But when the economy desperately needs more risk-taking investment, tempting people away from that risk-taking investment by letting people get high interest rates from a central bank is folly.

To the extent that banks turn to forms of risk-taking other than loans when the interest rate they can earn from the government goes down, I think it has a lot to do with the faulty approach of cutting interest rates a modest amount for a long time (or making large-scale purchases of long-term bonds), instead of cutting short-term interest rates sharply for a briefer period of time. Here, it is important to remember that there is no lower bound on the interest rates that can be earned from the government—except as a result of policy.

Dodd-Frank

In the November 2015 Bloomberg TV interview, Randal said:

In some ways Dodd-Frank was not ambitious enough, and in other ways it was overly ambitious and I think there are lots of ways to refine Dodd-Frank and other forms of regulatory policy in ways that would be beneficial to the economy.

I have no doubt that there are many flaws in Dodd-Frank. But given where financial industry lobbyists and many in Congress and the Administration may want to go, I view Dodd-Frank now as an important bulwark against weakened capital requirements. I also see the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau it established as important. In "On the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau" I argue there are

... three principles that can justify consumer financial protection beyond simple contract enforcement:

Duping people is fraud even if they wouldn’t have been duped had they had infinite time and infinite intelligence. ...

Facilitating gain for oneself and harm to others by taking advantage of preexisting confusion is predation of those who are especially vulnerable. ...

It is legitimate to protect time-slices of people from serious injury by other time-slices of people.

I don't have any problem with tinkering with Dodd-Frank to improve it—on two conditions: that Anat Admati and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's former Chief Economist Chris Carroll both endorse the modification to Dodd-Frank.

Tying the Government's Hands in a Situation Calling for a Bailout

In 2011, at the Atlantic Council think tank, Randal said

I have come to believe that there is a fundamental problem with resolution mechanisms that allow substantial discretion for governments to act in particular cases, which Dodd-Frank…does. The consequence of that is that it multiplies uncertainty in a time of crisis because you’re not going to act until you know what the government is going to do…as opposed to the admittedly more difficult, and perhaps unattainable, but I think ultimately the only really workable solution, which is to sort of have something that is like a bankruptcy regime—a rules-based approach as opposed to something that says, ‘and then ‘Mr. Wizard will decide what to do.’

I worry that what Randal calls "a rules-based approach" would, in fact, be an approach that tried to tie the government's hands so it could not do a bailout. But some situations call for bailouts. And it is hard for people writing the rules to fully put themselves in the shoes of those in the dire situation that calls for bailouts. Moreover, I think banning bailouts that would have much different effects in practice than in theory, because banning bailouts is not really banning bailouts—it simply puts legal obstacles in the way of bailouts that would still probably happen, but with even more uncertainty because of those legal obstacles.

As I said in my talk "Restoring American Growth,"

The moment you let banks [have] high leverage, that is the moment you've decided to do a bailout.

Trying to tie the government's hands so that, ex post, it can't do a bailout is unlikely to actually succeed in stopping a bailout, but is likely to make the bailout more costly. The better course is to prevent a bailout from being necessary in the first place by requiring that banks fund themselves much more by stockholder equity and much less by debt.

Conclusion

Let me emphasize that my criticisms of Randal Quarles' views above are not criticisms directed at Randal personally. From what little I know of him, I think he is more likely to modify his views in response to cogent arguments than most prominent people are. In "Meet Randal Quarles, Trump's Pick to Shake Up the Fed," Ryan Tracy writes:

Friends and former colleagues said that if Mr. Quarles does try to change direction at the Fed, they expect him to move slowly and methodically, and to seek consensus. ...

Ravi Menon, a Singaporean official who engaged in last-minute talks with Mr. Quarles on a U.S.-Singapore trade deal, wrote in 2004, “Right from the start, we took a problem-solving approach aimed at finding middle ground rather than trying to convert each other on ideological arguments.”

In other words, Randal is not as dogmatic as many of those who are in positions of power, and is open to persuasion. Nevertheless, unless he reconsiders his views, I worry that a vote for Randal Quarles is a vote for another financial crisis, simply because as things stand, he is not committed to doing whatever is possible to continue to raise capital requirements on banks.

Further Reading: "Martin Wolf: Why Bankers are Intellectually Naked"

John Locke: Freedom is Life; Slavery Can Be Justified Only as a Reprieve from Deserved Death

Marketplace for selling innocent individuals who were enslaved. John Locke's account of the "Law of Nature" suggests that those who did the enslaving deserved death or slavery themselves. Image source

In section 23 of his 2d Treatise on Government: “On Civil Government” (in Chapter IV "Of Slavery"), John Locke makes what I consider two logical errors. Taking as given the religious condemnation of suicide in his cultural milieu, he argues:

Since I do not have the right to kill myself, I also cannot give someone else the right to kill me.

Since freedom is so crucial to the preservation of my life, I also cannot give away my own freedom.

However, John Locke also suggests

If I commit a crime worthy of death, that the individual or group I have harmed can choose to commute a sentence of death to a sentence of slavery.

Being enslaved is no worse a punishment than death because, as a practical matter, it is very difficult to prevent me from killing myself if I viewed slavery as worse.

Here is the exact text:

This freedom from absolute, arbitrary power, is so necessary to, and closely joined with a man’s preservation, that he cannot part with it, but by what forfeits his preservation and life together: for a man, not having the power of his own life, cannot, by compact, or his own consent, enslave himself to any one, nor put himself under the absolute, arbitrary power of another, to take away his life, when he pleases. No body can give more power than he has himself; and he that cannot take away his own life, cannot give another power over it. Indeed, having by his fault forfeited his own life, by some act that deserves death; he, to whom he has forfeited it, may (when he has him in his power) delay to take it, and make use of him to his service, and he does him no injury by it: for, whenever he finds the hardship of his slavery outweigh the value of his life, it is in his power, by resisting the will of his master, to draw on himself the death he desires.

The lesser of the two logical problems is that John Locke effectively allows me to give away my freedom by committing a serious crime. So I can give away my freedom by committing a serious crime. John Locke could answer that since I do not have the right to commit the crime, I also do not have the right to give away my freedom in this way. And few people are eager to give away their freedom, so allowing such a loophole for giving away one's freedom is unlikely to be a practical problem. The usual temptations to give away one's freedom involve selling one's freedom in some way for something else one wants. And the usual temptations for crime are the hope of getting something one wants from the crime without losing one's freedom or suffering any other penalty.

The bigger logical disjunction here is that for some reason, John Locke regards suicide as an alternative to slavery as a legitimate choice, while suicide under other circumstances is not. But if suicide as an alternative to slavery is legitimate, why wouldn't suicide as an alternative to an extraordinarily painful and lingering terminal disease be legitimate? (Suppose everyone agreed that enduring the extraordinarily painful and lingering terminal disease was worse than enduring slavery.) Or if it is illegitimate to commit suicide as an alternative to suffering under an extraordinarily painful and lingering terminal disease, shouldn't suicide as an alternative to a situation of bondage more bearable than that disease also be illegitimate?

For links to other John Locke posts, see these John Locke aggregator posts:

John Locke's State of Nature and State of War (Chapters I–III)

On the Achilles Heel of John Locke's Second Treatise: Slavery and Land Ownership (Chapters IV–V)

John Locke Against Natural Hierarchy (Chapters VI–VII)

John Locke's Argument for Limited Government (Chapters VIII–XI)

John Locke Against Tyranny (Chapters XII–XIX)

Why GDP Can Grow Forever

Robert Gordon's argument that economic growth will slow down in the future made a big splash in 2012. He laid out his views in the Wall Street Journal op-ed shown above, as well is in other venues. His book The Rise and Fall of American Growth will come out on September 5, 2017.

A key part of Robert Gordon's argument is that dramatic changes in people's lives from past economic growth are unlikely to be repeated. He writes in his 2012 op-ed:

The growth of the past century wasn't built on manna from heaven. It resulted in large part from a remarkable set of inventions between 1875 and 1900. These started with Edison's electric light bulb (1879) and power station (1882), making possible everything from elevator buildings to consumer appliances. Karl Benz invented the first workable internal-combustion engine the same year as Edison's light bulb.

his narrow time frame saw the introduction of running water and indoor plumbing, the greatest event in the history of female liberation, as women were freed from carrying literally tons of water each year. The telephone, phonograph, motion picture and radio also sprang into existence. The period after World War II saw another great spurt of invention, with the development of television, air conditioning, the jet plane and the interstate highway system.

The profound boost that these innovations gave to economic growth would be difficult to repeat. Only once could transport speed be increased from the horse (6 miles per hour) to the Boeing 707 (550 mph). Only once could outhouses be replaced by running water and indoor plumbing. Only once could indoor temperatures, thanks to central heating and air conditioning, be converted from cold in winter and hot in summer to a uniform year-round climate of 68 to 72 degrees Fahrenheit.

The main claim a typical reader would take from this passage that it will be hard to make as big a difference to people's lives with the next 150 years of technological progress as with the last 150 years of technological progress. Robert Gordon may turn out to be wrong on all counts. Some believe a technological "singularity" will come within the next 150 years that will dramatically change human existence to something "transhuman."

But even if Robert Gordon is right that the next 150 years of technological progress will not make anywhere near as big a difference to people's lives as the last 150 years of technological progress, I have a highly technical criticism to his transition from that claim to his statement

The profound boost that these innovations gave to economic growth would be difficult to repeat.

Based on other things Robert Gordon has written, I interpret that as a statement about the effect of technological progress on real GDP growth. So interpreted, the statement "The profound boost that these innovations gave to economic growth would be difficult to repeat." may be true, but it does not follow logically from the difference technological progress has made to people's lives being hard to repeat.

The gap between "it is hard to repeat that improvement in people's lives" to "it is hard to repeat that boost to real GDP growth" has to do with what a weak reed real GDP growth is for understanding economic improvements. Let me leave aside all the many ways in which GDP can go up even if people's lives worsen. (See "Restoring American Growth: The Video" for a discussion of that.) If all non-market goods and parameters of income distribution stay the same and real GDP increases, people are indeed better off. But "How much better off?" What does it mean to say that GDP is 1% higher?

GDP was conceived with increases in quantity in mind. If people get more goods and services it is clear what an x% increase in GDP means. But more of exactly the same good or service becomes less useful very fast. If more people are getting goods that others already had, what is going on is also relatively clear. But what if enough people have all the want of exactly the same good or service they already have that entrepreneurs introduce a good that is in some respect new. It may be an entirely new good or something easy to see as an improvement in the quality of an existing good. In either case, the way government agencies factor this into GDP is that the value of the new good is measured by how much of more of the same people are willing to give up to get something new. Given how boring more of the same might be to at least some people, the amount some fraction of people are willing to give up of more of the same to get something new might be substantial. Therefore, the production of something wholly new or something seen as a higher quality modification of something old can count as a substantial addition to GDP growth.

In the extreme, if people became bored enough with more of the same, a set of truly tiny quality improvements could be counted as 3% growth in GDP, because a marginal 3% of boring products one doesn't need that much of is hardly any sacrifice at all.

My technical point is relevant not only to Robert Gordon's argument, but also to Tom Murphy's arguments in his posts "Can Economic Growth Last?" and "Exponential Economist Meets Finite Physicist." To his statement "economic growth cannot continue indefinitely," I say,

It depends what you mean by economic growth. If you mean GDP growth, all it takes for it to grow forever at a rate always above a positive x% per year is for tiny quality improvements or novelties to be valued extremely highly relative to a higher quantity of the same old things.

And it is not clear that what are seen as tiny quality improvements require any violations of the laws of physics, since quality improvements are all in the eye of the beholder.

Despite my framing of this post as a correction to Robert Gordon's and Tom Murphy's arguments, the real moral of this post is the imperfections of real GDP growth as a measure of "economic growth" in the broader sense of people getting more of what they want. GDP is a quantity-metric measure of economic welfare. If quantity is no longer very valuable, a quantity-metric measure shows small improvements in quality or novelty as equivalent to large increases in quantity.

Another way to look things is that Robert Gordon implicitly brings into his argument declining marginal utility. It is quite possible for economic growth to continue to be rapid by the conventional measure of GDP growth without it making as big a difference in people's lives as that rate of GDP growth made in the past.

Note: People's intuitions about declining marginal utility have other potential implications as well. See "Inequality Aversion Utility Functions: Would $1000 Mean More to a Poorer Family than $4000 to One Twice as Rich?"

Noah Smith: Seeking the Cure for American Economic Sclerosis →

I recommend the Bloomberg View article at the link above. These are tough issues. You can see my attempt to begin addressing them in "Restoring American Growth: The Video."

Let's Set Half a Percent as the Standard for Statistical Significance

My many-times-over coauthor Dan Benjamin is the lead author on a very interesting short paper "Redefine Statistical Significance." He gathered luminaries from many disciplines to jointly advocate a tightening of the standards for using the words "statistically significant" to results that have less than a half a percent probability of occurring by chance when nothing is really there, rather than all results that—on their face—have less than a 5% probability of occurring by chance. Results with more than a 1/2% probability of occurring by chance could only be called "statistically suggestive" at most.

In my view, this is a marvelous idea. It could (a) help enormously and (b) can really happen. It can really happen because it is at heart a linguistic rule. Even if rigorously enforced, it just means that editors would force people in papers to say "statistically suggestive” for a p of a little less than .05, and only allow the phrase "statistically significant" in a paper if the p value is .005 or less. As a well-defined policy, it is nothing more than that. Everything else is general equilibrium effects.

I previewed the paper and some of why tightening the standards for statistical significance could help enormously in "Does the Journal System Distort Scientific Research?" In the last few years, discipline after discipline has faced a "replication crisis" as results that were considered important could not be backed up by independent researchers. For example, here are links about the replication crisis in five disciplines:

Here is a key part of the argument in "Redefine Statistical Significance":

Multiple hypothesis testing, P-hacking, and publication bias all reduce the credibility of evidence. Some of these practices reduce the prior odds of [the alternative hypothesis] relative to [the null hypothesis] by changing the population of hypothesis tests that are reported. Prediction markets and analyses of replication results both suggest that for psychology experiments, the prior odds of [the alternative hypothesis] relative to [the null hypothesis] may be only about 1:10. A similar number has been suggested in cancer clinical trials, and the number is likely to be much lower in preclinical biomedical research. ...

A two-sided P-value of 0.05 corresponds to Bayes factors in favor of [the alternative hypothesis] that range from about 2.5 to 3.4 under reasonable assumptions about [the alternative hypothesis] (Fig. 1). This is weak evidence from at least three perspectives. First, conventional Bayes factor categorizations characterize this range as “weak” or “very weak.” Second, we suspect many scientists would guess that P ≈ 0.05 implies stronger support for [the alternative hypothesis] than a Bayes factor of 2.5 to 3.4. Third, using equation (1) and prior odds of 1:10, a P-value of 0.05 corresponds to at least 3:1 odds (i.e., the reciprocal of the product 1/10 × 3.4) in favor of the null hypothesis!

... In biomedical research, 96% of a sample of recent papers claim statistically significant results with the P < 0.05 threshold. However, replication rates were very low for these studies, suggesting a potential for gains by adopting this new standard in these fields as well.

In other words, as things are now, something declared "statistically significant" at the 5% level is much more likely to be false than to be true.

By contrast, the authors argue, results declared significant at the 1/2 % level are at least as likely to be true as false, in the sense of being replicable about 50% of the time in psychology and about 85% of the time in experimental economics:

Empirical evidence from recent replication projects in psychology and experimental economics provide insights into the prior odds in favor of [the alternative hypothesis]. In both projects, the rate of replication (i.e., significance at P < 0.05 in the replication in a consistent direction) was roughly double for initial studies with P < 0.005 relative to initial studies with 0.005 < P < 0.05: 50% versus 24% for psychology, and 85% versus 44% for experimental economics.

What about the costs of a stricter standard for declaring statistical significance? The authors of "Redefine Statistical Significance" write:

For a wide range of common statistical tests, transitioning from a P-value threshold of [0.05] to [0.005] while maintaining 80% power would require an increase in sample sizes of about 70%. Such an increase means that fewer studies can be conducted using current experimental designs and budgets. But Figure 2 shows the benefit: false positive rates would typically fall by factors greater than two. Hence, considerable resources would be saved by not performing future studies based on false premises. Increasing sample sizes is also desirable because studies with small sample sizes tend to yield inflated effect size estimates, and publication and other biases may be more likely in an environment of small studies. We believe that efficiency gains would far outweigh losses.

They are careful to say that in some disciplines, even the half-percent standard for statistical significance is not strict enough:

For exploratory research with very low prior odds (well outside the range in Figure 2), even lower significance thresholds than 0.005 are needed. Recognition of this issue led the genetics research community to move to a “genome-wide significance threshold” of 5×10^{-8} over a decade ago. And in high-energy physics, the tradition has long been to define significance by a “5-sigma” rule (roughly a P-value threshold of 3×10^{-7} ). We are essentially suggesting a move from a 2-sigma rule to a 3-sigma rule.

Our recommendation applies to disciplines with prior odds broadly in the range depicted in Figure 2, where use of P < 0.05 as a default is widespread. Within those disciplines, it is helpful for consumers of research to have a consistent benchmark. We feel the default should be shifted.

To me, one of the biggest benefits of this shift might be a greater ability for people to publish results that do not reject the null hypothesis at conventional levels. These results too, are an important part of the evidence base. The authors of "Redefine Statistical Significance" are careful to say that people should be able to publish papers that have no statistically significant results:

We emphasize that this proposal is about standards of evidence, not standards for policy action nor standards for publication. Results that do not reach the threshold for statistical significance (whatever it is) can still be important and merit publication in leading journals if they address important research questions with rigorous methods. This proposal should not be used to reject publications of novel findings with 0.005 < P < 0.05 properly labeled as suggestive evidence. We should reward quality and transparency of research as we impose these more stringent standards, and we should monitor how researchers’ behaviors are affected by this change. Otherwise, science runs the risk that the more demanding threshold for statistical significance will be met to the detriment of quality and transparency.

I myself was shocked when I read my own words above on the screen:

... people should be able to publish papers that have no statistically significant results: ...

That it seems shocking to say a paper should be publishable with no statistically significant results is a symptom of how corrupt the system has become. A stronger standard of statistical significance is needed in order to fight that corruption, both by making results that are declared statistically significant more likely to be true and by making results that are not declared statistically significant more publishable.

Update: Also useful is this article by Valentin Amrhei, Fränzi Korner-Nievergelt and Tobias Roth on "significance thresholds and the crisis of unreplicable research."

Western Values, According to Stephen Miller and Donald Trump

Toward the end of the period when I attended the Mormon Church (late 1999 and early 2000), I was still occasionally teaching Sunday School classes and more frequently teaching "Priesthood Meeting Elder's Quorum" classes. Despite views that varied significantly from Mormon orthodoxy at that point, I had no trouble teaching lessons in good faith. Assigned to teach from the text of a top Mormon leader's sermon, I would simply cross out the parts I disagreed with and teach the lesson based on what remained. And there was always something important that remained. I suppose some people might think what was remaining was trite, but I never did. The basics that people with diverging views agree on are often the deepest and meatiest truths of all.

My reaction to Donald Trumps speech in Poland on July 6, 2017 is similar. My disagreements with Donald Trump are profound—particularly on immigration: see for example

- "The Hunger Games" Is Hardly Our Future--It's Already Here

- Benjamin Franklin's Strategy to Make the US a Superpower Worked Once, Why Not Try It Again?

- Us and Them

- You Didn't Build That: America Edition

- Nationalists vs. Cosmopolitans: Social Scientists Need to Learn from Their Brexit Blunder

But I agree that what Donald Trump called "The West," deserves to be protected and defended, once one insists that anyone who accepts the values and principles of "The West" thereby becomes part of "The West," regardless of their national origin. (See my evocation of the principle of openness to newcomers in "'Keep the Riffraff Out!'")

And what are those values? Donald Trump's chief speechwriter Stephen Miller wrote a beautiful passage that were delivered in the Remarks by President Trump to the People of Poland | July 6, 2017:

We write symphonies. We pursue innovation. We celebrate our ancient heroes, embrace our timeless traditions and customs, and always seek to explore and discover brand-new frontiers.

We reward brilliance. We strive for excellence, and cherish inspiring works of art that honor God. We treasure the rule of law and protect the right to free speech and free expression.

We empower women as pillars of our society and of our success. We put faith and family, not government and bureaucracy, at the center of our lives. And we debate everything. We challenge everything. We seek to know everything so that we can better know ourselves.

And above all, we value the dignity of every human life, protect the rights of every person, and share the hope of every soul to live in freedom. That is who we are. Those are the priceless ties that bind us together as nations, as allies, and as a civilization.

Where "God" is mentioned, I need to interpret the passage according to my own view of God. (See "Teleotheism and the Purpose of Life.") And those with Western values are much more divided about the role of government than this passage recognizes. But otherwise I agree. And I hope you do, too, whatever your view of the man who wrote those words and the man who spoke them.

See also John O'Sullivan's thoughtful National Review article "Trump Defends the West in Warsaw"