The Economist’s recent list of the 25 most influential economists did not include a single woman. Many male former central bankers and regional Federal Reserve Bank governors were included on the list, but the Economist gave itself a special rule to exclude active central bankers, which meant that Janet Yellen—arguably the world’s most influential economist—didn’t make the list.

University of Michigan Professor and New York Times columnist Justin Wolfers responded with a tweeted list of influential women economists. You can read his whole tweetstorm on Twitter.

Why are top-notch female economists not being taken seriously? Why are they having trouble being recognized for their contributions to the profession? Why do women still have a hard time in the economics profession in general? There is no shortage of potential explanations.

In their recent academic paper “Women in Academic Science: A Changing Landscape,” Stephen J. Ceci, Donna K. Ginther, Shulamit Kahn, and Wendy M. Williams document the gender gap in economics and discuss many possible hurdles at each stage of a female economist’s career. And in a recent Bloomberg View article, University of Michigan Economics PhD Noah Smith adds to this list of potential hurdles the climate created by many male economists who defend their sexist views as hard-nosed truth telling.

One indication of the career challenges women face in economics is the fact that one of us felt the need to remain anonymous. The co-author of this piece is a still-untenured female economist who has withheld her name because there unfortunately could be real professional risks in publicly discussing many of these issues.

Many male economists underestimate the headwinds women face in economics, but they exist at every stage of a woman’s career. Just as an annual economic growth rate of about .33% per year in the 18th century and 1% in the 19th century transformed the world in the First and Second Industrial Revolutions, women in economics face many forces both large and small that add up to a huge overall damper on the number of women who make it to the higher ranks of our profession.

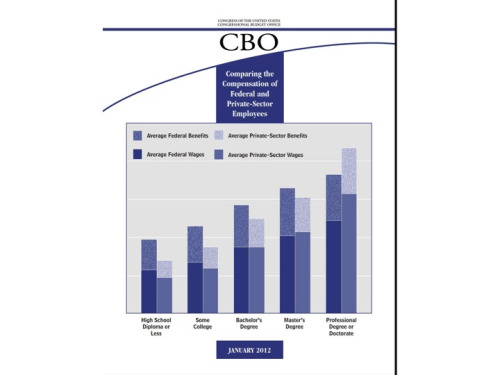

And even when women do reach these higher levels—despite the difficulty of getting their work published in male-dominated journals and in getting promoted even when they do get their work published—their wages remain lower.

In a Jan. 3 New York Times article, “Racial Bias, Even When We Have Good Intentions,” Harvard economist Sendhil Mullainathan argues that discrimination often operates at an unconscious level:

Even if, in our slow thinking, we work to avoid discrimination, it can easily creep into our fast thinking. Our snap judgments rely on all the associations we have—from fictional television shows to news reports. They use stereotypes, both the accurate and the inaccurate, both those we would want to use and ones we find repulsive.

The same sort of unconscious biases operate against women at every stage.

Here are a few of the issues women in economics face that their male colleagues might not be aware of:

- New female economics PhD’s have to worry about what to wear during the job market: skirt too short vs. too long, vs. just right.

- Female economists endure the nasty misogyny of many threads on econjobrumors.com.

- Students don’t give female professors the same respect as they do male professors. Compare ratings given to online teachers who represent themselves as female to one set of students and male to another, as in the experiment these instructors recently conducted.

- Female assistant professors have to worry about whether they dare take advantage of tenure clock extensions to have a child, while male assistant professors have no worries about taking advantage of the tenure clock extensions they get when their wives have a child. For the men, it is a simple strategic choice; for the women, it is reminder to their colleagues that (with rare exceptions) they bear the heaviest burden of taking care of a young child—a burden that might take time away from their research.

- Female professors are often inundated by students needing more “emotional” mentoring (a type of help many students assume they can’t get from male professors).

- Women in economics often get mistaken at social events for an economist’s spouse instead of being recognized as economists themselves.

- Female economists have to figure out how to deal with disrespectful comments or “jokes” made by their senior colleagues.

Fostering awareness of issues like these, and a hundred others of the same ilk, is one of the biggest things that can be done to improve women’s lot in economics.

Greater gender equality in economics could also be fostered by a better power balance among colleagues. What we mean is that female economists should be encouraged to assert their power, but male economists should find it hard or impossible to exert illegitimate, sexist power over their female colleagues. If this sounds obvious, it’s much harder than it seems.

Today, women in economics face a Catch-22, where speaking up can easily make them look like a shrew, while not speaking up robs them of legitimate power. There may be some loopholes in this Catch-22, but women starting out in economics need to be shown the ropes. And with so few senior female professors in economics, who can show a female graduate student how to promote herself gracefully, and break into predominantly male conversations without raising hackles? Somehow, that question needs to be answered. As more women push these boundaries, things will become easier. It may become possible to open up new ways of communicating and asserting power that allow women to be themselves and still have others listen to them carefully and respectfully.

If men are allowed to be jerks without suffering serious consequences, while women aren’t, then even well-behaved men have a threat-point that women are denied. One of the most primal reasons to treat someone nicely is the fear of a mistreated person’s anger or revenge. That doesn’t work well for women, because getting angry either makes them look like a harridan, or look overly emotional—both of which carry a big penalty in lost status.

It is easy to confirm that men are allowed to be jerks in ways that women aren’t—by flipping genders when someone does something out of line:

- What would you think of a particular man’s bad behavior if a woman you know did it?

- What would you think of a particular woman’s bad behavior if a man you know did it?

We don’t think the answer here is to change the culture so that women can be jerks, too, but to move toward holding everyone, both men and women, to account for bad behavior. For many men, it will be a revelation to be called out on the ways in which they demean others. Some may not even realize all the ways they routinely put others down—especially those in vulnerable positions who dare not strike back. But if you talk to a few women who spend time in economics departments, you will hear the stories.

Equal pay for equal work

Besides the threat point of men behaving badly, there is another threat point that gives men an advantage over women—one that gets men more than equal pay for equal work. It is typical in academia that a tenured professor who receives a competing job offer and can credibly threaten to leave gets a big raise. By comparison, professors who seem unlikely to jump ship end up underpaid. But given gender inequality on the home front (and the male-female wage differential for spouses), it is a lot more credible that a male professor can convince his wife to move to another city than that a female professor can convince her husband to move. This difference in ability to threaten to leave because of a spouse’s willingness to move is just one of the many ways that different levels of career support from spouses affects women in academia. The only thoroughgoing remedy for this inequity will come from greater gender equality throughout society.

(The situation is different when both wife and husband are academics, especially when they are both in the same discipline. Joint hiring decisions come up so often and go down so many different ways that no one should read any particular case into what we say. In general, because the couple forms a bargaining unit, some of the advantages men have in academia accrue to the wife in the husband-wife power couple. Women hired only because of their spouses—when they should have been hired in their own right—make academic departments look less sexist on paper than they really are. And when a woman who shouldn’t have been hired in her own right is hired in order to attract her spouse, it can be demoralizing to other women trying to make their way in academia on their own. Unfortunately, we don’t see any easy solution for the issues created by joint hiring decisions. But at a minimum they shouldn’t be allowed to distract economists from deeper issues of gender inequality.)

One final step that would make economics less forbidding for women is for each economist to become open to a wider range of scientific approaches and topics. Statistically, men and women are not drawn to the same fields within economics. And even within a field, women are drawn to a different balance between immediate real-world relevance and theoretical elegance. It is natural for each economist (and for each academic in general) to construct a narrative for why his or her approach to economics is the best. But since men in senior ranks in economics are more numerous than women, the narratives that men construct for why their individual approaches to economics are better usually win out in hiring and promotion decisions over the narratives that women construct for why their individual approaches are better.

This imbalance disadvantages junior women, whose individual approaches will on average have fewer champions. Here, the solution, difficult as it is, is for economists to appreciate the boost to scientific progress from having many different approaches and topics well represented—and for the subjective opinions of those who don’t appreciate the value of a wide range of approaches to be discounted. In particular, putting a premium on balancing theory with real-world understanding and policy action will not only make economics a stronger force for good in the world, it will help women take their rightful place in economics.