Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on the Three Basic Types of Business Models

In The Innovator’s Prescription, Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang make good use of a typology of business models laid out by C. B. Stabell and Øystein Fjeldstad in their May, 1998 Strategic Management Journal article “Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops and Networks.” Modifying Stabell and Fjeldstad’s terminology a bit for clarity, Clay and his coauthors call the three types of business models solutions shops, value-adding processes, and facilitated networks. Clay, Jerome and Jason argue that these three types of business models are so different that it is difficult to efficiently house them under one roof. They give these definitions for these three types of business models (from about location 360):

Solution Shops

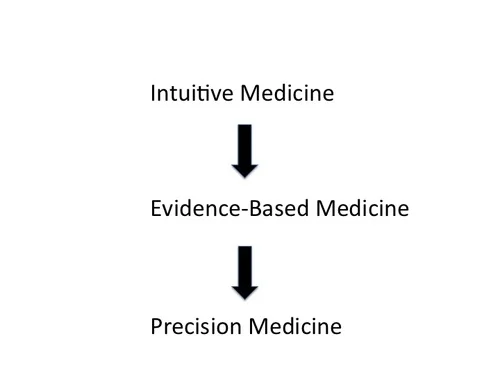

These “shops” are businesses that are structured to diagnose and solve unstructured problems. Consulting firms, advertising agencies, research and development organizations, and certain law firms fall into this category. Solution shops deliver value primarily through the people they employ—experts who draw upon their intuition and analytical and problem-solving skills to diagnose the cause of complicated problems. After diagnosis, these experts recommend solutions. Because diagnosing the cause of complex problems and devising workable solutions has such high subsequent leverage, customers typically are willing to pay very high prices for the services of the professionals in solution shops.

The diagnostic work performed in general hospitals and in some specialist physicians’ practices are solution shops of sorts. …

Value-Adding Processes

Organizations with value-adding process business models take in incomplete or broken things and then transform them into more complete outputs of higher value. Retailing, restaurants, automobile manufacturing, petroleum refining, and the work of many educational institutions are examples of VAP businesses. Some VAP organizations are highly efficient and consistent, while others are less so.

Many medical procedures that occur after a definitive diagnosis has been made are value-adding process activities….

Facilitated Networks

These are enterprises in which people exchange things with one another. Mutual insurance companies are facilitators of networks: customers deposit their premiums into the pool, and they take claims out of it. Participants in telecommunications networks send and receive calls and data among themselves; eBay and craigslist are network businesses. In this type of business, the companies that make money tend to be those that facilitate the effective operation of the network. They typically make money through membership or user fees.

Networks can also be an effective business model for the care of many chronic illnesses that rely heavily on modifications in patient behavior for successful treatment. Until recently, however, there have been few facilitated network businesses to address this growing portion of the world’s health-care burden. …

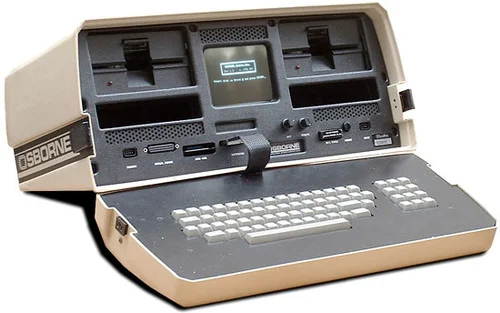

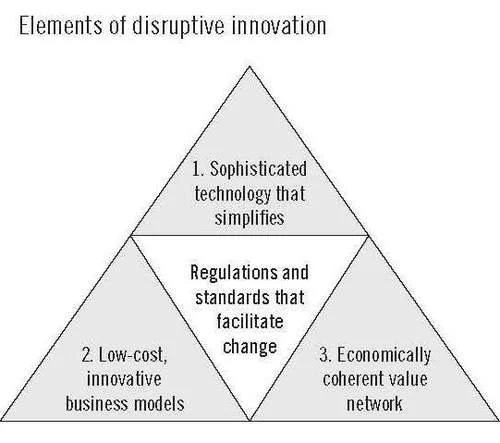

Clay, Jerome and Jason’s central idea is that medicine will be more efficient if there is one medical institution designed for inherently expensive “solution shop” activities such as difficult diagnoses, other much more convenient and inexpensive clinics for the routine treatment of well-diagnosed diseases, and online networks for patients to discuss their contribution as patients to disease management with others who have the same disease. What wouldn’t survive would be the current hospital model where the solution shop aspect of what they do confers high expense on many other activities that don’t have to be so expensive. Here is the way Clay, Jerome and Jason say it:

The two dominant provider institutions in health care—general hospitals and physicians’ practices—emerged originally as solution shops. But over time they have mixed in value-adding process and facilitated network activities as well. This has resulted in complex, confused institutions in which much of the cost is spent in overhead activities, rather than in direct patient care. For each to function properly, these business models must be separated in as “pure” a way as possible.

This is not just a matter of static efficiency:

The health-care system has trapped many disruption-enabling technologies in high-cost institutions that have conflated two and often three business models under the same roof. The situation screams for business model innovation. The first wave of innovation must separate different business models into separate institutions whose resources, processes, and profit models are matched to the nature and degree of precision by which the disease is understood. Solution shops need to become focused so they can deliver and price the services of intuitive medicine accurately. Focused value-adding process hospitals need to absorb those procedures that general hospitals have historically performed after definitive diagnosis. And facilitated networks need to be cultivated to manage the care of many behavior-dependent chronic diseases. Solution shops and VAP hospitals can be created as hospitals-within-hospitals if done correctly.

Further Musings: Even apart from this application to health care, I have found the typology of solution shop, value-adding process and facilitated network very interesting to think about for understanding my own work life (as a complement to the kind of analysis I talked about in my post “Prioritization”).

I work at the University of Michigan. Universities combine research–which is quintessentially a solution shop activity–with teaching, which has a big component of value-adding processes. And of course, Tumblr, Twitter and Facebook, where I put in effort as a blogger, are facilitated networks.

The idea of a value-adding process highlights the gains to be had from routinizing something. It is good to periodically ask oneself if there is anything in my daily activities that I can make more routine and streamlined.

The idea of a facilitated network highlights the gains to be had by having users do a lot of the work. That in turn is related both to the benefits of laissez faire under a decent system of rules and the idea of delegation, which typically involves giving up some control at the detailed level.

I find for me, however, that I love the “solution-shop” aspect of life so much that I think I resist routinization. I don’t know if this is what I should be doing, but I would rather keep thinking about how I am doing things than have everything fade into the background of routine. That does cost me extra time, as I do things inefficiently because I am thinking too much about them as I do them.

Here is a link to a sub-blog of all of my posts tagged as being about Clay Christensen’s work