Here is the full text of my 57th Quartz column, “Defending Clay Christensen: Even the ‘nicest man ever to lecture’ at Harvard can’t innovate without upsetting a few people,“ now brought home to supplysideliberal.com. It was first published on December 23, 2014. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

I wrote a version of this first as a blog post. I am delighted that my new editor at Quartz, Paul Smalera, liked it enough to publish it in Quartz. (My previous editor, Mitra Kalita, is now overseeing key aspects of Quartz’s global expansion.)

By the way, since I am blogging through Clay’s books (as I have been blogging through John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty) I have a virtual sub-blog on Clay Christensen:

http://blog.supplysideliberal.com/tagged/clay

In the column, I give my take on Clay’s theory as well as defending him personally.

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© December 23, 2014: Miles Kimball, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2017. All rights reserved.

**************************************************************************

Clay Christensen is not only the most famous management guru in the world, he is one of the few public figures—other than full time humanitarians or religious leaders—whom people go out of their way to describe as a good person. For example, in the Financial Times in November 2013, Andrew Hill described Clay Christensen, who had just won an award for most influential management thinker for the second time in a row, as “perhaps the nicest man ever to lecture at Harvard Business School.”

So I was surprised to see key Apple executive-turned-tech-entrepreneur Jean-Louis Gassée criticize not only Clay’s theories but also Clay’s character in his Nov. 25, 2014 Quartz article Clayton Christensen should really disrupt his own innovation theories. I want to defend Clay and his theories.

To be clear about where I am coming from, let me say that I can personally vouch for both Clay’s brilliance as a business thinker and his positive personal qualities. On the personal side, I carpooled across the country from Utah to Boston with Clay back in 1977 when I was beginning my freshman year at Harvard College and Clay was beginning to work toward his MBA from Harvard Business School. I have had relatively little contact with Clay since then, but still remember that trip as a bright moment in my life, and consider Clay a friend to this day. My daughter Diana’s experience as a Harvard MBA student in Clay’s class only reinforced my impression that Clay is one of the best human beings I have met.

My views on Clay as a thinker come from reading six of Clay’s books this year:

As an economist, I found them fascinating. One of the hottest areas of economics in the last twenty years has been the border between economics and psychology. One basic idea at that intersection is that people have limitations in their ability to process information and make decisions. This idea that cognition is finite is a key issue in macroeconomics, as Noah Smith and I wrote about in “The Shakeup at the Minneapolis Fed and the Battle for the Soul of Macroeconomics—Again.” But the idea of finite cognition also matters a lot for businesses. Some decisions are hard even for people who spend their careers making those kinds of decisions, and the support of teams of experts.

Clay, in the management theory he has developed with various coauthors, identifies one key factor in how hard a decision is for a generally well-run business: whether it involves taking care of what are already the business’s core customers, or trying to sell to either peripheral customers or people who have never bought from the business before. No business is successful for any significant length of time if it doesn’t do a reasonably good job of taking care of its core customers. But being good at understanding and serving its core customers may make it bad as an organization at understanding and serving peripheral or potential customers.

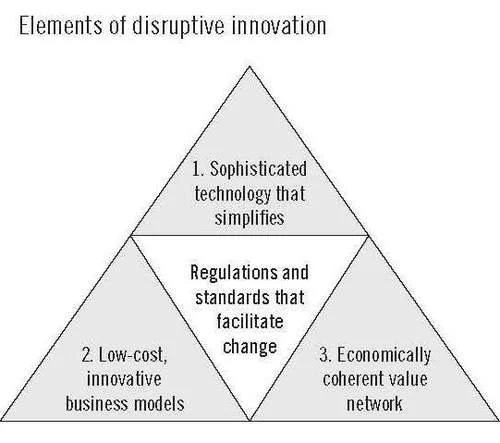

Clay’s famous warnings about “disruptive innovation” boil down to saying that any set of peripheral or potential customers a business doesn’t serve well—even if those non-core customers look relatively unprofitable—might provide a ladder for a competitor to climb up and eventually overtake that business. And since the main part of a business is designed to serve its core customers, it may need to set up a separate unit to act like a start-up and focus on other potential customers.

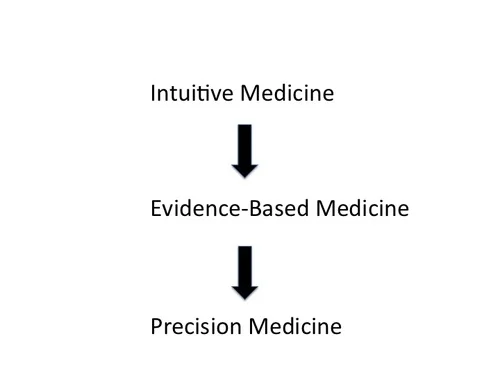

When Clay turns to public policy issues in education and health care, the idea of innovative upstarts overtaking an established business by starting with underserved customers or non-customers morphs into the idea of reforming education and health care by finding chinks in the armor of the status quo. The key public policy recommendation I draw from Clay’s logic is that policy should be supportive of organizations doing things in new ways that help people on the margins who find the current systems difficult to navigate, even if those new approaches don’t improve quality for those who are currently well served by the status quo.

Here is Gassée’s own summary of Clay’s theory:

The incumbency of your established company is forever threatened by lower-cost versions of the products and services you provide. To avoid impending doom, you must enrich your offering and engorge your price tag. As you abandon the low end, the interloper gains business, muscles up, and chases you farther up the price ladder. Some day—and it’s simply a matter of time—the disruptor will displace you.

The first charge Gassée makes against Clay is that Clay is a very persuasive, high-priced consultant who advises rival companies:

… in the mid-to-late 1980s, parlayed his position into a consulting money pump. He advised—terrorized, actually—big company CEOs with vivid descriptions of their impending failure, and then offered them salvation if they followed his advice. His fee was about $200,000 per year, per company; he saw no ethical problem in consulting for competing organizations.

In Clay’s case, I get the sense that he is giving almost every company a variant of the same advice, which is more concerned with potential competitors who might not even be in the picture yet, rather than existing competitors. So I can see why two rival companies might both feel comfortable hiring Clay. As to the price, I also find Clay’s insights valuable, so I am willing to go with the default view of economists that if someone is willing to pay a lot of money for something, it is an indication that they find it quite valuable.

Gassée’s next charge is that Clay is arrogant:

The guru and I got into a heated argument while walking around the pool at one of Apple’s regular off-sites. When I disagreed with one of his wild fantasies, his retort never varied: I’m never wrong.

Had I been back in France, I would have told him, in unambiguous and colorful words, what I really thought, but I had acclimated myself to the polite, passive-aggressive California culture and used therapy-speak to “share my feelings of discomfort and puzzlement” at his Never Wrong posture. “I’ve always been proved right…sometimes it simply takes longer than expected,” was his comeback.

Hyperbole—”exaggerated statements or claims not meant to be taken literally”—has its place in conversation (for example, there is every indication that the historical Jesus frequently used hyperbole). So the exact tone of voice and context matter a lot. The management consulting context is one in which hyperbole might be appropriate in order to help counteract an attachment by someone one is advising to the status quo. In that context, saying “I’m never wrong” might mean simply “You should really, really, listen to my advice.” Given the magnitude of Clay’s claims, if Clay sincerely believes in the advice he is giving, as I suspect he does, the sentiment “You should really, really, listen to my advice” is understandable.

Gassée’s last charge is that Clay became defensive and lashed out when his work was challenged by Jill Lepore. Here is what Gassée has to say about that:

Christensen is admired for his towering intellect and also for his courage facing health challenges—one of my children has witnessed both and can vouch for the scholar’s inspiring presence. Unfortunately, his reaction to Lepore’s criticism was less admirable. In a Businessweek interview Christensen sounds miffed and entitled:

“I hope you can understand why I am mad that a woman of her stature could perform such a criminal act of dishonesty”

In this case, fortunately, the context is known. You can see Drake Bennett’s Businessweek interview “Clayton Christensen Responds to New Yorker Takedown of ‘Disruptive Innovation‘” here. Clay told Drake

… she starts instead to try to discredit Clay Christensen, in a really mean way. And mean is fine, but in order to discredit me, Jill had to break all of the rules of scholarship that she accused me of breaking—in just egregious ways, truly egregious ways. In fact, every one—every one—of those points that she attempted to make [about The Innovator’s Dilemma] has been addressed in a subsequent book or article. Every one! And if she was truly a scholar as she pretends, she would have read [those]. I hope you can understand why I am mad that a woman of her stature could perform such a criminal act of dishonesty …

So Clay’s intemperate phrase “criminal act of dishonesty” is about Jill Lepore writing as if Clay hadn’t ever given any answer to the kinds of questions she raises. A specific case later in the interview clarifies what is angering Clay. Here is Drake Bennett’s question:

Another point Lepore makes is that you leave out relevant factors that would challenge your thesis. In the case of the steel industry, you don’t talk about unionization, which was a major difference between U.S. Steel and upstart minimills.

Clay replied:

Yes and no. The world is actually very complicated and big huge books are written about unionization and the impact that it has, and so … other people have addressed that.

If she’s interested, there’s a case that I use in my course about U.S. Steel that occurred in 1989. There the union contract in Mon Valley Works [one of U.S. Steel’s plants] was a huge factor. So, again, if she were thorough on this issue and she Googled it and put in my name and U.S. Steel, that would have come up. But because her purpose was to discredit me rather than look for the truth, she didn’t even look. Are you feeling a little bit about how she’s caused me to feel?

That is, Clay thinks Jill Lepore did not do even the most basic homework to see if Clay had any subtlety to his views. Here, actually, Lepore’s point is about how differential unionization might weaken the evidence for Clay’s theory of disruptive innovation, which Clay’s Harvard Business School case might not have done anything to address, so Lepore’s fundamental point might stand, but she should have made that argument. And while it may be unreasonable to expect someone writing a magazine article to know one’s whole body of work before vigorously criticizing a piece of it, it is reasonable to expect her to try to talk to Clay to get his side before publishing a traditional-style long-read article attacking Clay’s work. This is a point Clay himself makes:

… if she’s interested and wants to help me—she’s just an extraordinary writer—and if she’s interested in the theory or its impact, I mean, come over! I would love to have you openly invite her to come do this, if she’s interested.

(Like Clay, Jill Lepore is at Harvard.)

I think Drake Bennett is right that Clay was quite angry at Jill Lepore’s article:

Consistently described by those who know him as a generous and thoughtful and upbeat person, he is also capable of fury. “Keep asking me questions,” [Clay] said, “it’s helping me.”

But, I am not going to change my view of Clay as one of the best human beings I have met for controlled anger in a situation like that.

No one is perfect. But in order for us to have a hope of becoming better human beings, we need to at least know which direction is up. Despite his flaws, I don’t know anyone who wouldn’t do well to become a little more like Clay in at least some respect.