Miles's First Radio Interview on Federal Lines of Credit

Bill Greider’s piece in The Nation’s blog on Federal Lines of Credit (see “Bill Greider on Federal Lines of Credit: ‘A New Way to Recharge the Economy”) was syndicated to the Detroit Metro Times (the link under the credit card), which in turn sparked a radio interview with Detroit Public Radio.

I listened back to the podcast myself and thought it turned out well. So I recommend it. It is short and sweet.

By way of clarification on Bill Greider’s piece, The Detroit Metro Times posted this note from me. The reply to Mike Konczal that note describes as forthcoming is already out as my post “Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football.”

You Didn't Build That: America Edition

Before Barack said

Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business–you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.

with an intonation pattern that was a little confusing given his likely intent, he said this:

Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive.

It is good to see that discussion of what Barack said has gone beyond “gotcha” to a discussion of deeper philosophical issues. Even Rush Limbaugh has turned philosopher, discussing the underlying issues that Barack raises. (Here is my review.)

I am moved by the statement

Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have.

Leaving aside the rest of Barack’s speech, there is an important message in this. Those of us alive now didn’t build this unbelievable American system from scratch. Those who have gone before us have handed down to us something precious. I think the right response to that gift is gratitude, a determination to do our part to preserve the wondrous aspects of that system, and a desire to share the benefits of this unbelievable American system with others.

When I say “share the benefits of this unbelievable American system with others,” I mean what I say. And it is something that far transcends the importance of our current debates about taxing and spending policy. It is churlish of us to shut others out from the benefits of this unbelievable American system. The framers of our Constitution and the others who did the most to put together this unbelievable American system had an open attitude toward immigration. And we know that as late as 1883, these words were engraved on a bronze plaque on the Statue of Liberty, where they can still be seen to this day:

The New Colossus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Emma Lazarus, 1883

This is my policy on immigration, as I think it should be the policy of the United States Government and the policy of the People of the United States. We didn’t build this unbelievable American system, and it is not our private property. We don’t have a moral right to exclude other human beings–human beings like us–from the benefits of this unbelievable American system. As stewards of this unbelievable American system, we need to regulate the pace of arrival so that the system itself is not overwhelmed and destroyed, but unless this unbelievable American system itself is threatened, let us open our doors wide to others who have not had the good fortune to be born Americans.

Magic Ingredient 1: More K-12 School

In my book, the two truly wonderful things Barack has done on the domestic front are advancing gay rights (through ending “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and more recently by rhetorical support for gay marriage rights) and advancing education reform through the brilliant work of Arne Duncan as his Secretary of Education. By dangling a few gigadollars worth of grant money in front of states, Arne has gotten states to fall all over themselves passing education reforms that I would have thought impossible in such a short time–often with buy-in from the teachers unions. I cheer on this effort and other efforts at education reform.

Although I am in favor of more school choice, including both charter schools and Milton Friedman’s still excellent idea of education vouchers, let me focus in on two aspects of education reform that can be fully implemented within regular public schools: increasing the total amount of schooling kids get in their K-12 years and making sure they are legally qualified to pursue a wide range of careers when they earn a high school diploma.

Sometimes the most important fact in a given area is one so obvious it might not even seem worth saying. I heard one such fact from a top researcher in education at an academic seminar at the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center: the single most important variable in predicting whether a student will get a test question right is whether that topic was covered in class or not. Students don’t always remember what they were taught. But they never remember something they weren’t taught. More time in school means more things can be taught at least once, and the more important things can even be repeated a few times.

The secret recipe behind the “Knowledge is Power Program” or KIPP schools (which have been very successful even with highly disadvantaged kids) is this:

- They motivate students by convincing them they can succeed and have a better life through working hard in school.

- They keep order, so the students are not distracted from learning.

- They have the students study hard for many long hours, with a long school day, a long school week (some school on Saturdays), and a long school year (school during the Summer).

The KIPP schools also have highly motivated teachers, but that is a topic for another day.

So my first proposal for this post is to go to a 12-month school year, and to extend the school day until at least 5 PM (but with many extracurricular activities and sports being eligible to count as part of the school day, as they do in Japan). Research has shown poor kids and rich kids learn at a somewhat similar rate during the school year, but that poor kids forget a lot during the Summer, while rich kids retain more. So lengthening the school year is especially helpful for poor kids. Lengthening the school year and the school day also effectively provides year-round day care for poor parents who desperately need it. For rich families who are used to being able to go on a summer vacation, I would allow families to make proposals for family or individual activities with educational value that could substitute for some part of school in the summer, and grant permission for these substitutions for summer school relatively liberally for anything that research shows keeps kids academically sharp. The poor kids will think this is unfair, but they simply need the formal schooling more because their parents can’t afford other high-quality educational activities. So keeping them in school during the summer really is doing them a favor.

I won’t try to work out all the details of how the longer school day and school year would work, but I need to address one objection that will spring to many readers minds: extra costs. I don’t want to assume massive new infusions of money into schooling that might never be available. But I think it can be done without major additional costs. The school buildings are there anyway, year round, so the major expense to worry about is teacher salaries. Here I think we could start by having each teacher teach the same number of annual hours as they now do, but staggered throughout the year. (Over time, on a merit basis, some teachers could be allowed to work year round at a commensurately higher salary, to make up for normal attrition.) The margin that would give is that class sizes would go up. Except in Kindergarten, and maybe in 1st grade, higher class sizes have been shown by research to have only a small effect on learning–probably less than a tenth the effect on learning on the minus side that more total school hours for the kids would have on the plus side. We might need to knock out a few walls between classrooms to accommodate these larger class sizes, but it could be done. (Note that the total number of kids in school at any one time would be basically the same as now, so the kids would fit.) Even with these expedients, costs would go up some. For example, the lights would have to be kept on longer. But I think it should be manageable. And the fact that some of the rich kids wouldn’t be there in the summer would either help bring down class sizes for the poor kids then, or allow school districts to save on staffing during the summer.

Much of the extra schooling time from the longer school day and longer school year would go toward learning the basics better–reading, writing, math–and maybe getting a little extra cultural background that will help students enjoy a wider range of things in their lives. But I want to claim some of the extra time to make sure that the kids are legally qualified to do a wide range of jobs when they finish school. One of the most important drifts of political economy at the state level in the United States has been toward requiring licenses for more and more jobs. Here is what Morris Kleiner and Alan Krueger say in their 2008 National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper “The Prevalence and Effect of Occupational Licensing”:

We find that in 2006, 29 percent of the workforce was required to hold an occupational license from a government agency … Our multivariate estimates suggest that licensing has about the same quantitative impact on wages as do unions–that is about 15 percent …

Many economists and other observers feel that occupational licensing has gone too far. Here is an interesting Wall Street Journal article:

Dick Carpenter and Lisa Knepper WSJ “Do Barbers Really Need a License?”

And here is an article from what I think is a Libertarian website (“The Library of Economics and Liberty”):

S David Young, “Occupational Licensing”

Others argue that health and safety and basic competence really do require training even for many jobs that sound easy, such as cutting hair or cutting nails.

What I want to do is to restrain the tendency to go overboard on occupational licensing while allowing genuinely necessary competencies to be transmitted by requiring states to ensure that their schools high school tracks that would make it reasonably possible to be meet the legal qualifications for any of at least 60% of all licensed occupations, with each student able to be qualified with his or her high school diploma for at least 10% of all licensed occupations. Then the graduates might actually be able to get a job. This requirement for getting the Federal education grant could be met by any combination of reducing licensing requirements and increasing effective training that each state chose. I am sure that states would game the rule, so that the overall effect would be less than what this sounds on the surface, but it would be better than the way things are now, where students graduating from high school are kept out of many of the more desirable occupations by occupational licensing restrictions.

Many schools these days have a program that allows more ambitious students to earn an Associate’s degree (equivalent to two years of college) before their time in publicly-funded high school education runs out. For them, I would add the requirement that states make it possible for ambitious students doing the equivalent of an Associate’s degree to be licensed for any of 50% of medical care jobs. (Being a doctor would still require much, much more training. Note: “any” is not the same as “all.” They would have to do some choosing.) This would not only help these students get jobs, it would help us as a nation to be able to afford the medical care that we want.

Note that any reduction in occupational licensing restrictions increases the value of having readily available and accurate quality ratings for services as well as goods. To be honest, in my personal experience, which I think will match that of most of my readers, I have seldom been satisfied with services from the bottom half of those in any occupation. But the stratification into different quality levels should be handled by the market as much as possible (and by government fiat as little as possible), with continually improved web-based ratings mechanisms. High school graduates need entry-level jobs, even though it is hard to be really good at anything at first before accumulating experience, especially for those who would not have been able to get jobs at all without the changes I am advocating.

Let me end by explaining my title. In his recent post “What it to be done now, Jeff Sachs appears to miss the point by a substantial margin,” Brad DeLong lays out his short-run Keynesian program for the economy, and says this about Jeff Sachs’s column:

When I started Jeff’s column, I thought it was going to be an exercise in hippie-punching, along the lines of: “Simplistic Keynesian remedies will not solve our problems. See, I am a Very Serious Person. What will solve our problems is X.” And X would turn out to be simplistic Keynesian remedies plus some magic ingredient Y. That might have been useful. It would have been a call for simplistic Keynesian policies plus magic ingredient Y.

As I discussed in my immediately previous post “Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football” I am all for more aggregate demand right now, as long as it is achieved in ways that don’t ultimately add too much to the national debt, but what Brad DeLong’s words sparked in me was a desire to come up with “magic ingredient Y” for long run growth and improvement in the economy. Thinking that there might be many magic ingredients that can help in the long run–hopefully more than there are letters in the alphabet, I am going to start off with numbers. Hence, “Magic Ingredient 1: More K-12 School.”

Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football

Mike Konczal has a recent post “Four Issues with Miles Kimball’s ‘Federal Lines of Credit’ Proposal," announced by this tweet:

Mike’s tweet is the only way I can get a working link to his post. This link may work at some point in the future. Here is Mike’s description of my proposal:

What’s the idea? Under normal fiscal stimulus policy in a recession, we often send people checks so that they’ll spend money and boost aggregate demand. Let’s say we are going to, as a result of this current recession, send everyone $200. Kimball writes, "What if instead of giving each taxpayer a $200 tax rebate, each taxpayer is mailed a government-issued credit card with a $2,000 line of credit?” What’s the advantage here, especially over, say, giving people $2,000? “[B]ecause taxpayers have to pay back whatever they borrow in their monthly withholding taxes, the cost to the government in the end—and therefore the ultimate addition to the national debt—should be smaller. Since the main thing holding back the size of fiscal stimulus in our current situation has been concerns about adding to the national debt, getting more stimulus per dollar added to the national debt is getting more bang for the buck.”

Mike has some praise and four Roman numerals worth of objections. I promised a detailed answer. Other than the comment threads after each post, this is only the second time I have had a serious online criticism of one of my posts, and I will try to accomplish the same sort of thing I tried to accomplish in my answer to the first serious criticism I received from Stephen Williamson: to answer the criticism point by point while at the same time making some important points worth making even aside from this dustup with Mike. The main point I want to make uses the phrases “fiscal policy” and "stabilization policy,“ which can be given the following rough-and-ready definition:

Fiscal policy: government policy on taxing and spending

Stabilization policy: loosely, recession-fighting (in times of recession) and inflation-fighting (in times of boom).

More precise definitions of stabilization policy inevitably involve the details of exactly what should be done and when, which are sometimes under dispute; this definition will serve for now. Here is the main point I want to make in this post:

Long-run fiscal policy is unavoidably political, since it involves the tradeoff between the benefits of redistribution and the benefits of low tax rates, but stabilization policy can and should be kept relatively apolitical. The politicization of stabilization policy in the last few years is an unfortunate, and fundamentally unnecessary, turn of events.

By avoiding big changes in taxes or spending, I hope my Federal Lines of Credit proposal can help to depoliticize stabilization policy.

The reason a discussion of the politicization of stabilization policy belongs in a reply to Mike Konczal is that my simple summary of his objections to my Federal Lines of Credit proposal of government-issued credit cards to stimulate the economy is that my proposal does not do enough to redistribute toward the poor. Now my views on redistribution are no secret. As I said in my first post, "What is a Supply-Side Liberal,” redistribution is good. In my post “Rich, Poor and Middle-Class,” I made a stronger statement, focusing on helping the poor, which is the important part of redistribution:

I am deeply concerned about the poor, because they are truly suffering, even with what safety net exists. Helping them is one of our highest ethical obligations.

The other type of redistribution, which is more controversial (because the redistributive benefit is smaller and the economic efficiency cost is higher) is taxing the rich in order to help the middle class. Given the fact that redistribution needs to be financed by taxes or by deficit spending, Republicans and Democrats differ substantially on how much redistribution they think should be done of either type. As a result, the political fights over long-run taxing and spending policy are often bitter. My fervent hope is to find ways to avoid having the the blood that is spilled over long-run taxing and spending policy from infecting short-run stabilization policy, which by rights should be less controversial especially in a recession, since recessions are bad for almost everyone. It is a little harder to say that inflation is bad for almost everyone, since inflation benefits debtors at the expense of creditors, but few people on either side of the political divide advocate high inflation as a way to wipe out debts, and most of the other effects of inflation higher than a few percent per year are bad for everyone.

What has made stabilization policy a political football in the last few years is the fact that the Federal Reserve is maxed out on its favorite recession-fighting tool of lowering short-term interest rates. Because currency effectively earns an interest rate of zero, no one is willing to lend money at an interest rate much below zero, so zero is about as low as the Fed can go. In my answer to the first serious criticism I received from Stephen Williamson, I argue that the Fed can still do a lot more to stimulate the economy even when the nominal interest rate is already down to zero, but the Fed has been reluctant to use unfamiliar tools to the full extent possible. And the size of the necessary changes to the Fed’s balance sheet are enough to scare many people (in a way that I argue is unwarranted in my third, and to this date, most-viewed post “Balance Sheet Monetary Policy.”) Indeed, the Fed has become a political target not only because of its sadly necessary role in saving the economy by bailing out big banks, but also because even the Fed’s half-measures have involved big enough changes in the Fed’s balance sheet to scare many people.

Besides monetary policy, the traditional remedies in stabilization policy have to do with taxing and spending. In particular, the traditional remedies for a recession other than monetary stimulus are tax cuts and spending increases. It is easy to see the problem. Since taxes and spending are also the center of the political debate about long-run policy, any use of taxes or spending to fight recessions arouses justifiable suspicion that the other side will use recession-fighting as an excuse to advance its long-run agenda: for Republicans, lowering taxes in the long run, for Democrats, increasing the amount of redistribution in the long run.

By contrast, since monetary policy does not touch on what in recent history are the core political debates about taxing and spending, for at least the 30 years from mid 1988 to mid 2008 (when the financial crisis and the Great Recession threw things for a loop) political controversies over monetary policy have been relatively esoteric–not the sorts of things that move the average voter in either party.

In crafting my Federal Lines of Credit proposal, one of my key objectives was to find a new way of fighting recessions that, like monetary policy in normal times, would be fully acceptable to both political parties. The U.S. economy and the world economy are in trouble, and it is important that politics not get in the way of what needs to be done. So I am pleased to have Mike Konczal say of my proposal “This has gotten interest across the political spectrum.” The proposal itself is described in my second post “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy,” and my recent post “Bill Greider on Federal Lines of Credit: 'A New Way to Recharge the Economy’” is a good way to catch up on the discussion about Federal Lines of Credit since then.

Now let me turn to Mike’s four issues:

I. Isn’t deleveraging the issue? Is this a solution looking for a problem? From the policy description, you’d think that a big is credit access holding the economy in check.

But taking a look at the latest Federal Reserve credit market growth by sector, you can see that credit demand has collapsed in this recession.

I actually think that credit access has gone down. For example it is a lot harder getting home-equity lines of credit these days than it used to be, even for those whose houses are worth a lot more than their mortgages. But Mike is right that many people are scared enough about the economy that they are trying to pay down their credit card debt. The key point here is that what makes sense from an individual point of view in time of recession–reducing household spending–makes things worse for all of us by reducing the amount of business that firms get and therefore how many workers feel they can hire. So to help out the macroeconomic situation, we want people to lean toward spending more than they otherwise would. Giving every taxpayer access to a federal line of credit at a reasonable interest rate and reasonable terms (say 6%, paid off over 10 years) would cause at least some people to spend more, which is what we want in order to stimulate the economy.

II. This policy is like giving a Rorschach test to a vigilante. No, not that vigilante. I mean the bond vigilantes.

Mike’s point here is that, although in the long-run, people will have to pay back the money they borrowed from the government on their Federal Lines of Credit, the government is out the money in the meantime, and this might add to the official deficit and national debt numbers. So if the folks in the bond market are not smart enough to look past the surface of the deficit and national debt numbers, they might cause long-term interest rates to go up. Here, my answer is simple: the folks in the bond markets are very, very smart. They know the difference between the government being out money forever (as it would be if it used a tax rebate) and the government making loans that will be repaid, say, 90% of the time. As evidence that the “bond vigilantes” look at more than the official debt to GDP ratios, take a look at this list of debt to GDP ratios. (I am using the International Monetary Fund’s numbers from this table, rounded off to the nearest percent. If there are more recent numbers, I am confident they will show the same thing.) Here are the examples that make my point:

Spain: 69%

Germany: 82%

United States: 103%

Japan: 230%

It is right to worry about the future, but currently, Spain is in trouble with the bond vigilantes, while the world is eager to lend money to Germany, the United States and Japan. (See my post “What to Do When the World Desperately Wants to Lend Us Money” about what this eagerness of the world to lend to the U.S. means for U.S. policy from a wonkish point of view that ignores political difficulties.) The reason Spain is in trouble with the bond vigilantes is that the Spanish government is seen to be on the hook for the much of the debts of Spanish banks; this bank debt that may become Spanish government debt sometime in the future does not show up in the official debt to GDP figures, but the bond vigilantes know all about it. On the other end, one reason that the bond vigilantes are still willing to lend money to Japan at low interest rates is that they know Japanese households do a lot of saving and don’t like to put their money abroad, so a lot of that saving makes its ways into Japanese government bonds, either directly or indirectly.

III. This policy will involve trying to get blood from a turnip. I very much distrust it when economists waive away bankruptcy protection. Especially for experimental, controversial debts that have never been tried in known human history.

As the paper admits, this is a machine for generating adverse selection, as the people most likely to use it are people whose credit access is cut due to the recession. High-risk users will likely transfer their balances from higher rate credit cards to their FOLC (either explicitly or implicitly over time if barred) - transferring a nice chunk of credit risk from the financial industry to taxpayers.

It’s also not clear what happens a few years later when consumers start to pay off the FOLC. Could that trigger another recession, especially if the creditor (the United States) doesn’t increase spending to compensate?

The issue isn’t whether or not the government will be able to collect these debts at some point. It has a long time-horizon, the ability to jail debtors and use bail to pay debts, the ability to seize income, old-age pensions and a wide variety of income, and the more general ability to deploy its monopoly on violence. The question is whether this will be smoother, easier, and more predictable than just collecting the money in taxes. We have a really smooth system for collecting taxes, one at least as good as whatever debt collection agencies are out there. If that is the case, there’s no reason to believe that this will satisfy the bond vigilantes or bring down our debt-to-GDP ratio in a more satisfactory way.

Mike actually raises several issues here. Let me be clear that I am not proposing jailing debtors! I am imagining something like the current system we have for student loans directly from the Federal government. These loans cannot be wiped away by bankruptcy, but no one is jailing former students who can’t pay what they owe on their student loans. When I supposed above that (including interest–I am thinking in present values) only 90% of the money would be repaid, the other 10% is money that the government ultimately gives up on trying to collect because some people can’t pay. To avoid any possible abuses, I think it would be a good idea to specify in the law authorizing Federal Lines of Credit that people’s debts under the program could never be sold to an outside collection agency: only official government employees would be allowed to make collection efforts. Worry about a political firestorm would prevent the government from doing the kinds of things the private collection agencies sometimes do. Almost all repayment would be through payroll deduction from people who are drawing a paycheck, with perhaps some repayment through small deductions from government transfers people receive when those government transfers are above a minimum level.

Is an expected loan-loss rate of 10% too much? Then it is easy to modify the program to reduce the loan-loss rate without reducing its effectiveness in recession-fighting by allowing those with higher incomes to borrow more and restricting the size of the lines of credit for those with lower incomes. For those worried about issues with Federal Lines of Credit like those Mike is raising, I strongly recommend reading my relatively accessible academic paper on the proposal: “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy.” But now I am going to give you fair warning about what “relatively accessible” means by quoting the somewhat recondite way that I make this point in the paper:

One of the main factors in the level of de facto loan losses would be the extent to which the size of the lines of credit goes up with income. Despite the reduction in additional aggregate demand per headline size of the program that might be occasioned by conditioning on income, de facto loan losses would probably decline by a greater proportion, meaning that conditioning on income might improve the ratio of extra consumption to budgetary cost. Certainly, having the line of credit go up with income might reduce the level of implicit redistribution, which is a consideration I will not try to address here.

To translate, if we give rich taxpayers bigger lines of credit than poor taxpayers, we will probably get even more bang-for-the-buck from the program–in the sense that there will be more stimulus for each dollar ultimately added to the national debt after most repayment has happened.

I will confess that the only reason I didn’t make this kind of dependence of the size of the line of credit on income the benchmark version of the proposal is that I wanted to sneak in a little income redistribution into the program. But if next year we have a Republican Congress and a Republican President (now trading at a 30% probability on Intrade), stimulating the economy is important enough that it is still a very good thing to do the Federal Line of Credit program with less redistribution than I had in the benchmark version of the proposal, which gives the same-size line of credit to each taxpayer. On the other hand, if next year we have a Democratic Congress and a Democratic President (now trading at a 7.5% probability on Intrade), stimulating the economy is important enough that it is still a very good thing to do the Federal Line of Credit program with lines of credit of the same size not only for every taxpayer but also for non taxpaying adults and to let the debts be extinguished in bankruptcy. Federal Lines of Credit would still give us more bang-for-the-buck than other types of fiscal stimulus that a Democratic Congress and Democratic President might turn to, and regardless of what happens politically, the United States government does have to worry about the bond vigilantes down the road whenever it adds to the national debt in a long-run way. In what I consider the most likely case of divided government, where out of the presidency, the Senate and the House of Representatives, each party holds at least one (now trading at a 62.5% probability on Intrade if one includes the 4.5% probability of “other,” which presumably covers the case when the control of one house of congress depends on how the few independents vote), something in between–perhaps not too far from my benchmark proposal–seems to me what would be politically feasible.

In the passage I quoted from Mike labeled as his issue III, he also worries about whether the repayment of the loans would cause a recession later on. I have thought that stretching out repayment over 10 years would be enough to avoid this problem, but I view this an issue for the experts. If, as I prefer (see my post “Bill Greider on Federal Lines of Credit: 'A New Way to Recharge the Economy’”), the Federal Reserve determines many of the details of the Federal Lines of Credit Program, I trust the staff of the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve Banks to come up with a better answer on the appropriate length of time for loan repayment than either Mike or I could.

Finally, we come to Mike’s fourth and last issue, which motivated my discussion above about the value of separating long-run fiscal issues from short-run stabilization policy, so that recession-fighting doesn’t become a political football. What Mike writes to explain his fourth issue is long enough that I will intersperse some comments along the way. From here on, everything in block quotes reproduces Mike’s words.

IV.Since we’ve very quickly gotten to the idea that we’ll need to jettison legal protections under bankruptcy for this plan to work, it is important to emphasize that this policy is the opposite of social insurance.

As I said above, I am not advocating jailing debtors. I don’t see the fact that student loans are not expunged in bankruptcy as a massive social injustice that causes huge problems; if it is, it would meant that it is a travesty that the Obama administration is only proposing having private student loans wiped away by bankruptcy while leaving public student loans from the government untouched by bankruptcy. I am sure some people think that, and would not be surprised if that is Mike’s view, but I don’t think the average voter would take that view, nor do I criticize the Obama administration for not being willing to go far enough and have all student loans expunged in bankruptcy.

I don’t see a macroeconomic difference between the government borrowing 3 percent of GDP and giving it away and collecting it through taxes later versus the government borrowing 3 percent of GDP, loaning it to individuals, and collecting it later through debt collectors except in the efficiency and the distribution.

This passage is well-designed to underemphasize the fact that the way in which, say, “3 percent of GDP” is given away is redistributive. Indeed, to the extent that asking everyone to pay the same amount is regressive, giving everyone the same amount as in my benchmark proposal has to count as anti-regressive. There is no question that giving away 3 percent of GDP and collecting it later through progressive taxes would bemore redistributive. Overall, my program is fairly neutral as far as redistribution goes, though as I confessed, I snuck a little redistribution into my benchmark proposal because those with higher incomes would likely repay a bigger fraction of the borrowed money than those with higher incomes.

The distributional consequences of this proposal aren’t addressed, but they are quite radical. Normally taxes in this country are progressive. Some people call for a flat tax. This proposal would be the equivalent of the most regressive taxation, a head tax. And it also undermines the whole idea of social insurance.

Mike seems to be claiming that the Federal Lines of Credit program overall is regressive. I just don’t see this. Is the government’s student loan program regressive? Just because a program could be made more redistributive than it is, does not mean that on the whole it is regressive.

Let’s assume the poorest would be the people most likely to use this to boost or maintain their spending. I think that’s largely fair - certainly the top 10 percent are less likely to use this (they’ll prefer to use high-end credit cards that give them money back). This means that as the bottom 50 percent of Americans borrow and pay it off themselves, they would bear all the burden for macroeconomic stability through fiscal policy. Given that the top 1 percent captured 93 percent of the income growth in the first year of this recovery, that’s a pretty major transfer of wealth. One nice thing about tax policy, especially progressive tax policy, is that those who benefit the most from the economy provide more of the resources. This would be the opposite of that, especially in the context of a “"relatively-quickly-phased-in austerity program.”

Let me say quickly that my mention of “austerity” was in the European context, where paying what the bond market demands without a full-scale bailout from a reluctant Germany requires austerity. I made no mention of “austerity” for the U.S., nor do I think “austerity” will be necessary for the U.S., if we follow the kinds of proposals I recommend.

Going back up to the top of this block quote from Mike, again, saying that the bottom 50 percent of Americans “would bear all the burden for macroeconomic stability” ignores the fact that they were able to borrow and use the money when they really needed it during hard economic times. The only way in which this could be a burden is if loaning money on relatively favorable terms (again, say at 6% for 10 years) is an unkind temptation to people who have trouble stopping themselves from spending more now than they should. I worried about this, which is why I proposed that, by the time the next recession rolls around, we have National Rainy Day Accounts set up that allow people to spend in recessions or during documentable personal financial emergencies money that they have saved up previously. Now requiring someone to save money for later emergencies they might face, and encouraging them to spend some of that money in a national emergency such as a future recession may indeed be a burden. But it is hard for me to see how both proposals–letting people borrow on favorable terms from Federal Lines of Credit and requiring people to save in National Rainy Day Accounts–can be a burden. The only way that allowing people to borrow on favorable terms can be a burden is if they have trouble saving as much as they should, in which case setting up a structure to help them save will help them out. And Mike agrees that “There’s a lot to like about the proposal [Federal Lines of Credit], particularly how it could be used after a recession is over to provide high-quality government services to the under-banked or those who find financial services yet another way in which it is expensive to be poor …" On a more negative note, Mike continues as follows in the text of his fourth issue:

Efficiency is also relevant - as the economy grows, the debt-to-GDP ratio declines, making the debt easier to bear. The most likely borrowers under FOLC [sic], the bottom 50 percent, have seen stagnant or declining wages overall, especially in recessions. A growing economy would keep their wages from falling in the medium term, but this is still a problematic issue - their income is not more likely to grow to balance out the payment burdens than if we did this at a national level, like normal tax policy.

The policy also ignores social insurance’s role in macroeconomic stability, and that’s insurance against low incomes. Making sure incomes don’t fall below a certain threshold when times are tough makes good macroeconomic sense and also happens to be quite humane. This is not that. As friend-of-the-blog JW Mason said, when discussing this proposal, the FOLC [sic] is like "if your fire insurance simply consisted of a right to borrow money to rebuild your house if it burned down.”

Here again, I take Mike’s point that it would be easy to do more redistribution than the modest amount of redistribution in the Federal Lines of Credit proposal as I lay it out. But I view redistribution as the province of long-run fiscal policy (in the broadest sense). Trying to use recession-fighting as a way to also do more redistribution is a recipe for making recession-fighting a political football. If recession-fighting becomes a political football, as it has to an unfortunate extent in the last few years, the recession (or the long tail of unemployment that follows what are officially called “recessions”) wins. And bad economic times are especially hard on those at the bottom of the income distribution. So they can least afford to have recession-fighting become a political football. My hope is that Federal Lines of Credit will make it possible to stimulate the economy when necessary in a way that avoids major changes in taxing and spending that would set off alarms for one or another of the two warring parties in the political debate.

What to Do About a House Price Boom

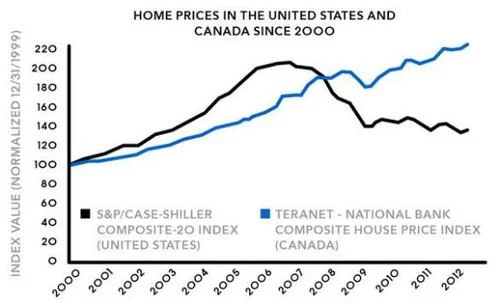

Matthew Yglesias asks in his post today what a country is supposed to do about a housing boom:

Ever since American house prices started declining, people who predicted that this would happen have been crowing and slagging policy elites who failed to see it coming. I think in some ways the better question is what are you supposed to do about these situations?

He goes on to point out that this is a relevant question for Norway and Canada now:

Right now everyone seems to agree that Norway is experiencing an unsustainable house price boom. You may have recently heard the factoid that Canadian household wealth is now higher than U.S. household wealth, but this too certainly looks like an unsustainable house price boom.

I don’t know enough about Norwegian and Canadian institutions to have a well-informed answer for them (though I hope what I say will be useful), but with the benefit of a time machine, there are three good answers for the United States.

First, the mortgage interest deduction is unfortunate in any case, since it tilts people toward borrowing over saving. What may be worse, it tilts our economy towards building more houses and fewer factories, when we should be tilting things the other way. Almost all of the benefit of a house goes to the owner. By contrast, a factory not only benefits its owner with a stream of rentals on that factory (often called profits), but also employs people which benefits those workers in a way not captured by the owner of the factory. So if there were equal tax treatment of factories and houses, there would still be too few factories. The mortgage interest deduction skews the balance further in the direction of houses, soaking up some of the construction resources that could otherwise have gone to building factories that employ people not only in the process of being built but even after they are built.

So the mortgage interest deduction is unfortunate. But a time like now when falling house prices continue to drag our economy down is not a good time to lower house prices further by phasing out the mortgage interest deduction. On the other hand, a boom in house prices provides a golden opportunity to reduce the mortgage interest deduction, especially if you catch the boom early, so that stopping it doesn’t result in a big crash.

Second,if we could go back in time and do things right, surely we would restrict low-downpayment mortgage loans as a way of reining in booming house prices and minimizing the likely damage in any subsequent period of declining house prices.

Third, if we could go back in time and do things right, I hope we would adopt regulations to encourage risk sharing in home prices, as recommended by Andrew Caplin here and by Robert Shiller in his new book Finance and the Good Society. A big reason for our current troubles is that homeowners bore the full brunt of the declines in house prices, up to the point of foreclosure. With risk sharing, other investors would take some of these losses, and of course to make that worth their while, they have to know they will share in some of the gains when house prices go up, or be paid some sort of insurance premium. The government can help. Currently, IRS regulations effectively discourage home price risk sharing contracts of the sort that Andrew Caplin recommends. And the kind of adjustment of the principal of mortgages according to what happens to home price indexes that Robert Shiller recommends (and indeed, helped start the Case-Shiller home price index in order to someday make possible), would be a big change in the customs of the real estate markets that could be speeded along greatly by regulations that encouraged such provisions.

In short, there are many things worth doing if one sees a house price bubble starting up. And the encouragement of risk-sharing in house prices is not just something we should have done, it is something that the U.S. should be working on now, to prevent problems in the future. There is no law of nature that says that homeowners need to suffer from regional or even national house price declines any more than people whose houses burn down should be left without a house or a family whose breadwinner dies should be left financially bereft. This is avoidable suffering. We should have insurance for house prices just as we have fire insurance and life insurance. And though private industry can handle house price insurance just fine once house price insurance gets going (with the same kind of government oversight we have for other types of insurance), we’ll get house price insurance a lot sooner if the government lends an extra hand at the beginning.

Dr. Smith and the Asset Bubble

Dr. Noah Smith of Noahpinion, soon Assistant Professor at Stony Brook

I sometimes hear professors (including myself) bemoan our lack of power. Then I remind them that we have the amazing power to mint A’s–a power many undergraduates would love to have. It is just that in an institution well-constructed to minimize self-interested decisions, one doesn’t get to have the power one really wants, say the power to set one’s own salary –but some other power, such as the burdensome power and duty to assign grades.

Another–but this time totally welcome–power that professors often have is to grant Ph.D.’s. 20 hours ago, after Noah’s dissertation defense, Bob Barsky (sadly for me, now of the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank), Yusufcan Masatlioglu, Uday Rajan and I drew up the documents that will grant Noah Smith his Ph.D.

As has been the tradition in economics at least since I was in graduate school a quarter century ago, Noah’s dissertation has three chapters, each of which it is hoped will, within a few years (after the usual many rounds of revisions demanded by editors and the referees they enlist) become an article in an economics journal. Noah’s first two chapters are on asset bubbles–rapid, and somewhat mysterious, rises and then falls of the price of some asset, such as the rise and fall of internet stock prices around the turn of the millennium and the more recent rapid rise and fall of home prices. Noah describes the research in his first chapter and job market paper “Individual Trader Behavior in Experimental Asset Markets” in his post “What are asset bubbles and why do they happen?” The remarkable thing in “the literature” (the array of academic papers) on asset price bubbles that Noah adds to is that asset price bubbles happen even in the laboratory of a stock trading game with real people in which everyone is told exactly how the payouts of a “stock” are determined, say by flipping a coin to determine whether the “dividend” is 10 cents or zero each turn. So it is almost inevitable that asset bubbles will happen in the real world, which is a lot harder to figure out. To some, this may seem an obvious point, but a large share of opinions that economists give about the financial markets are based on intuition from theoretical models in which asset bubbles never, ever occur, because the “agents” in the models–who are intended as stand-ins for real people–are too smart.

Let me be clear. Studying models of financial markets in which agents are too smart for asset bubbles to ever occur is a worthy, and even at times noble, endeavor. But when it comes to real-world policy decisions, economists need to bring to bear everything we know about the world, even things that we have had a tough time analyzing in formal economic models. And we need to keep in mind especially those facts about the world that remind us of our own ignorance. When I took a first-year macro class in graduate school from Larry Summers, Larry had a practice of presenting a model and then promptly proceeding to tear it down. I went up after class to complain that this was very discouraging. Larry Summers said something I have never forgotten: “It isn’t easy to figure out how the world works." Larry Summer’s maxim

It isn’t easy to figure out how the world works

is an excellent mantra for an economist to repeat to himself or herself several times before giving policy advice.

The reason it is nevertheless OK to study models that leave out important facts about the world is that as economists, we need to walk before we can run, and models in which the agents are very smart are a lot easier to analyze than more realistic models in which some agents are very smart and others do strange, not-so-smart things. (I was tempted to put in the word "suboptimal” in place of “not-so smart.” “Suboptimal” is a word economists use for an action that is not the best action one could be taking from the standpoint of one’s own objectives.) Brad Delong, Andrei Shleifer, Larry Summers and Robert Waldmann published a more realistic model like this in 1991 that was a huge advance. But it is a baby model of this type compared to the complexity of the real world.

One reason that (although often forgivable in an academic paper), assuming people are smart enough to avoid bubbles is at violence with reality is that, as Noah’s research shows, it is not enough for each trader to understand asset payouts herself or himself. The suspicion that other traders don't understand can lead to speculative trading. Also, Noah argues that people can understand what is going on one minute, but then doubt themselves the next minute when they see asset prices that suggest other people don’t agree. All the changes to experimental setups that are known to do the most to extinguish asset bubbles have one common property: they not only help each trader to act in a smarter way, they also help make each trader believe that other traders will act in a smarter way. Here are some examples:

- Running the asset market over and over from the beginning with the same set of traders. (See Vernon Smith, Gerry Suchanek and Arlington Williams.)

- Calling the “stock” a “stock in a depletable gold mine,” which helps people understand that the total amount of payouts left will go down as the game draws to a close. (This comes from an unpublished working paper “Thar she bursts–a critical investigation of bubble experiments” by Michael Kirchler, Jurgen Huber and Thomas Stockl.)

A similar point can be made in relation to Noah’s second paper on asset bubbles in the lab: “Private Information and Overconfidence in Experimental Asset Markets.” This paper documents that investors not only trade on their own inside information, but also make trades with other investors who have insideinformation. (Noah’s research also shows that the amount of such trading is not closely related to existing measures of overconfidence. It isn’t easy to figure out how the world works.) In theoretical models, the super-intelligent agents realize that anyone who wants to trade with you should be looked at with suspicion: “What does he or she know that I don’t?” And in fact, the insight that you should wonder what the other guy knows that you don’t is important. Let me quote Noah’s comments on the intriguing paper “Are investors really willing to disagree: an experimental investigation of how disagreement and attention to disagreement affect trading behavior” by Jeffrey Hales:

Finally, a very interesting experiment by Hales (2009) investigates the closely related question of whether traders “agree to disagree” about the value of an asset. In his experiment, subjects trade in pairs and receive private signals about asset value. Hales finds that whether traders are prompted to consider the adverse selection problem has a strong effect on whether trade occurs. When traders are asked to guess the difference between their own signal and the signal of the other trader, trade tends not to occur; however, without such prompting, trade does tend to occur. This result suggests that over-reliance on private information is not due to traders “agreeing to disagree,” but simply to their failure to consider the fact that others have information that may disagree with their own. [Emphasis added.]

This intervention (asking people to focus on the difference between their signal and the signal of the other trader), like interventions 1 (repeating the game) and 2 (calling the stock a stock in a depletable gold mine) above, gains a lot of its power from changing what each trader visualizes is going on in the heads of the other traders.

Noah’s third chapter is joint work with Bob Barsky and me: “Affect and Expectations.” (It is common for dissertations in economics to include one out of three chapters that is joint work with advisors.) This paper shows that it is misnomer to call consumer confidence indexes measures of “consumer sentiment,” if by “sentiment” one means something emotional. (To back up the idea that people really do call it “consumer sentiment” see for example the title of the wikipedia article on the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index.) For a variety of purposes, I had arranged to have the University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers collect data on happiness from the people surveyed. Noah and Bob and I analyzed how movements in happiness compared to movements in expectations about the economy. We could measure a relationship, but it was very small. So movements in consumer confidence are not primarily about fluctuations in happiness. And it is hard to think of many emotions that don’t show up as having some effect on happiness, so it would not be easy to defend the idea that some other emotion is the primary mover of consumer confidence. People’s confidence in the economy does go up and down in a big way. But something that doesn’t show up in happiness movements–and so something that is probably not emotional in the usual sense–is the primary cause of fluctuations in consumer confidence.

It isn’t easy to figure out how the world works. (Larry Summers, 1984.)

Update: Ever since I wrote this post I have been wracking my brain trying to remember whether Larry Summers told me “It isn’t easy to understand how the world works” as in an earlier version of this post, or “It isn’t easy to figure out how the world works.” At first, I dismissed “figure out” because that is a favorite phrase of mine and I feared I had substituted that into my memory. But I keep coming back to “figure out.” And it occurred to me that maybe one of the reasons I like “figure out” may be precisely Larry Summers using it in this context. In any case I have decided to edit the repeated quotation to the “figure out” form. If anyone knows from Larry’s speech patterns which he would have been more likely to say, let me know.

By the way, this is a good place to let readers know that I have enough of a random, patchwork, perfectionistic impulse that I routinely allow myself silent edits in my blog posts without an update notification. I am not running for office, I am not on trial, and I already have tenure, so I don’t have to play the game of “gotcha.” In my case, it is my words that matter, not me, and the words that matter are the ones I am willing to stand behind in the end.

But in this case, the “It isn’t easy to understand how the world works” version of the quotation has already gone out into the world and even become the title of a blog post by Kevin Grier–“Angus” at Kids Prefer Cheese, so I feel I need to clearly signal this particular update. On other occasions, clearly signaling an update helps to drive home the overall point of a post. And if I ever write on some other website, I will follow the norms there.

Adam Ozimek on Worker Voice

Richard Freeman, author of What Do Unions Do?

I love Adam Ozimek’s post “How to Improve Working Conditions” It encapsulates very well what I think Adam and I both learned from the work of Harvard Professor Richard Freeman–especially his influential book What Do Unions Do? Richard Freeman says that unions have two effects:

- Unions raise wages and benefits above what the workers in the union would otherwise get, which is much like a tax on a firm hiring workers and causes similar distortions. (The main difference from a tax is that the workers get the money from the “employment tax” instead of the government.)

- Unions communicate to firms the details of what workers want (and gather information from the workers in the union to be able to do this), often identifying ways to make workers better off that are worth more to the workers than they cost the firm, so that they increase the total size of the pie to be divided between workers and the firm.

Number 2 is the “worker voice” that Adam praises.

The simple bottom line on unions is this:

Raising wages or benefits and so making it harder for people to get jobs, bad. Making life better for workers in common-sense ways, good.

We can have the good, worker voice, without the bad, a worker-imposed employment tax that reduces employment and output, by adopting Adam’s proposal of encouraging worker associations as opposed to traditional unions. Workers need an organization that can speak for them. But they don’t need traditional unions that hurt the economy by grabbing for a bigger share in the short run.

Paul Romer's Reply and a Save-the-World Tweet

I sent an email to Paul Romer to let him know about my post giving kudos to his idea of Charter Cities. Here is his reply, which I share with you with his permission. (Note: Paul’s links, unlike mine, stay in the same window, so use the backarrow to return instead of closing the window.)

Miles, good to hear from you. Thanks for the kind words.

Surprisingly to me, soon after I gave this talk, I was approached by people from the government in Honduras, which has taken many steps toward implementing a version of this idea.

See for example,

“Hong Kong in Honduras” in The Economist

“Who Wants to Buy Honduras?” in the New York Times

Readers who want more information could check out

Cheers, Paul

I believe in Charter Cities.

I think many of you will feel the way I feel about Paul Romer’s Charter City idea, too, if you take 19 minutes to watch

this video of Paul Romer’s TED talk.

If I am right and you do agree with me on this, let me ask you to engage in a bit of activism with me:

Here is a link to my first save-the-world tweet in what I want to propose as the supplysideliberal community’s first save-the-world tweet campaign: Charter Cities.

If you retweet this save-the-world tweet, together we might be able to get a snowball of tweets in favor of Charter Cities going that will let a lot many more people know about this idea that could change the world.

To help get things started, I have temporarily put a link labeled “Learn about our save-the-world campaign for Charter Cities” at the top of my sidebar links. It redirects to this post.

Miles Kimball and Brad DeLong Discuss Wallace Neutrality and Principles of Macroeconomics Textbooks

Let me provide a glossary for this discussion, in order of appearance terms that might be less familiar to some readers. But having written what is below, it is clear to me that it is more than a glossary. It has my most careful explanation yet in this blog of many key concepts. So it is worth reading even if you know what all of the terms mean.

IS-LM: The standard model of macroeconomics as taught in most undergraduate macroeconomics textbooks that many economists believe is a reasonable description of what causes business cycles despite the fact that it is hard work to get IS-LM-like results from economic models at the research frontier. IS stands for “combinations of output and interest rates where investment equals saving.” LM stands for “combinations of output and interest rates where liquidity demand for money L equals supply of money M."

grok: to understand. Here is the wikipedia definition of grok. Brad’s use of grok from Robert Heinlein’s book Stranger in a Strange Land references our shared interest in science fiction. Brad’s posting of this on his blog gives some evidence of his interest in science fiction.

ZLB: The "zero lower bound” on the nominal interest rate. That is, the fact that interest rates can’t go significantly below zero. (“Nominal” just means interest rates the way non-economists talk about them, as contrasted with the “real” or “inflation-adjusted” interest rates beloved of economists.) Why can’t the interest rate go much below zero? Because anyone can earn an interest rate of zero by burying cash in the back yard or hiding it in their mattress, so no one is willing to buy a bond that pays much below zero. People might buy a bond that pays a little below zero simply because it is more convenient than burying currency in the backyard, but they won’t accept an interest rate much below zero. The zero lower bound on the nominal interest rate is a problem for monetary policy since the Fed usually stimulates the economy by lowering short-term interest rates, which have recently been very close to the lower bound of zero.

AD: Aggregate demand, or the amount of spending people will do at a given price level. In models where prices adjust instantly to any change in the macroeconomic situation, aggregate demand is not very important; it only affects the price level and not much else. But in models that have sticky prices (any form of slow adjustment of the price level to new situations) aggregate demand governs the size of GDP in the period of time before prices adjust. Background: both Brad and I believe that in the real world, prices adjust only slowly to changes in the macroeconomic situation.

Keynesian model: In this context a component of IS-LM: what happens when not only the price level, but also interest rates are held constant. The reason that the zero lower bound (ZLB) is relevant here is that being pressed down against the floor of zero by the Fed is a reason why the interest rate might in fact stay constant in the face of a wide range of changes in the macroeconomic situation. In other contexts “the Keynesian model” might be a synonym for “IS-LM.

20-yr T < 0: Brad is saying that the inflation-adjusted (real) interest rate on 20-year Treasury bonds is now less than zero. In other words, if you buy 20-year Treasury bonds right now, what you earn will probably fall behind inflation. There is an ongoing discussion in the blogosphere about what the low interest rates on long-term Treasury bonds means for economic policy. See my post "What to Do When the World Desperately Wants to Lend Us Money.” In his tweet, Brad is simply pointing out how close to zero a wide range of interest rates paid by the U.S. government are right now. The implication is that the zero lower bound is starting to look relevant for long-term interest rates paid by the U.S. government as well as short-term interest rates paid by the U.S. government.

Wallace neutrality: In reference to either an economic model or to reality, Wallace neutrality is the statement that monetary policy can affect the economy in an important way if it the monetary policy action changes the path of current and future short-term interest rates paid by the government. Although Ben Bernanke does not believe that Wallace neutrality applies to the real world, the influence of Wallace neutrality thinking on the Fed is clear from the emphasis the Fed has put on telling the world what it is going to do with interest rates in the future. When the economy is at the zero lower bound, Wallace neutrality in the real world would mean that the only way the Fed could stimulate the economy now would be by promising to overheat the economy in the future, as I discuss in my post “Should the Fed Promise to Do the Wrong Thing in the Future to Have the Right Effect Now?” I have a series of other posts also discussing Wallace neutrality. In fact, essentially all of my posts listed under Monetary Policy in the June+ 2012 Table of Contents are about Wallace neutrality.

Noise traders: People who not only fail to make the best possible investment decisions for themselves but alsomake their mistakes in big enough herds that they move markets, changing the prices of stocks, bonds and other assets. (Note: Investors can make mistakes in herds for many reasons, not just what is called “herding behavior” in the economics literature.) The name “noise traders” suggest herds of investors who move markets by their actions, but herds of investors can also move markets by inaction in the fact of government actions. In models, Wallace neutrality arises from investors responding in highly intelligent ways to actions of the government that cancel out the effects of the government’s actions.

OLG: Having to do with “overlapping-generations” models, in which investors regularly die or otherwise leave the market and are replaced by other investors. Since I think investors stick around in asset markets for many years, and it requires fast turnover of investors to get much short-run action from overlapping generations models, this is not where I would turn to for a plausible model of departures from Wallace neutrality. Some sort of failure to optimize on the part of investors in herds as in the definition of “Noise traders” above is much more promising. The one other promising micro-foundation (story about what individual households and firms are doing) for departures from Wallace neutrality that I can think of is institutional structures that make firms behave differently than an optimizing investors would–for example, if assets rated AAA are required to meet certain regulatory or legal requirements.

Ricardian neutrality: See my post “Wallace Neutrality and Ricardian Neutrality” and the wikipedia article on “Ricardian Equivalence.” "Ricardian equivalence" is a synonym for “Ricardian neutrality." Economists use these phrases interchangeably and about equally often. The substance of Ricardian neutrality is actually not crucial to our discussion. We are looking at the status of Ricardian neutrality from a philosophy of science perspective and comparing it to the status of Wallace neutrality from a philosophy of science perspective.

Baseline modeling status: Both Ricardian neutrality and Wallace neutrality reflect how the simplest economics models behave within the category of "optimizing models.” Optimizing models are models that have in them very intelligent agents in them who do what is best for themselves. Both Brad and I agree that simple optimizing models should be the starting point for thinking about how the world works. Saying a model has baseline modeling status is saying that it should be the starting point for thinking about how the world works. The discussion is then about what might plausibly make things behave differently in the real world from that theoretical starting point. In other words, sometimes the starting point is a good place to stop, given the value of simplicity to human understanding; but sometimes the starting point is a bad place to stop because it misses an aspect of reality that is too important. In the case of balance sheet monetary policy, it is not enough to say that given what central banks have done in the past, Wallace neutrality is a good approximation, it is important to know whether Wallace neutrality is a good approximation over the full range of things that central banks could do. See my post “Future Heroes of Humanity and Heroes of Japan” for the kind of dramatic monetary policy move I have in mind when I say this.

Home bias: The well-documented tendency of investors to have a larger fraction of their assets in the stocks, bonds and other assets of their home country than would be warranted if they were trying to minimize the risk they face in order to get a certain level of expected returns. In other words, there is evidence that individual investors act as if they have a prejudice against foreign assets.

Effect of foreign assets purchases counts: I am saying that if the Fed bought Japanese or German bonds, for example, it would have an effect on exchange rates and the net exports of the U.S. and other countries, even when U.S. short-term interest rates are essentially at zero (the ZLB). Simple optimizing models imply that real (inflation-adjusted) exchange rates and net exports would be unaffected by the Fed buying Japanese or German bonds when short-term interest rates in the U.S. are already essentially zero (an example of Wallace neutrality), but I think many economists would predict that large purchases of Japanese or German bonds by the Fed would have an important effect. I have promised a future post on “International Finance: A Primer” explaining all of this better. (Based on sad experience, I have stopped promising specific dates for future posts, unless they actually exist in finished form in my queue.)

Long term T-bonds not powerful: Departures from Wallace neutrality should be especially small for long-term Treasury bonds for two reasons: (a) their interest rates are already fairly close to zero, so it is not that easy to bring them down further, and (b) there are many very smart traders in government bond markets with a lot of money behind them. What departures from Wallace neutrality there are for purchases of long-term government bonds probably arise more from institutional structures than from failures to optimize. In addition to likely having only a small departure from Wallace neutrality, buying long-term Treasury bonds is not ideal for balance sheet monetary policy for reasons forcefully argued by Larry Summers and discussed in my post “What to Do When the World Desperately Wants to Lend Us Money” There, within the Fed’s comfort zone, I recommend that the Fed buy mortgage backed securities. (I will discuss the issues with having the Fed buy foreign assets in a future post. Also see what Joseph Gagnon has to say about this.) Alternatively, the Fed could look for authority to buy a wider range of assets, either in interpretation of existing law or by asking Congress for authority to buy a wider range of assets, as it successfully asked for the authority to pay interest on reserves.

Everything the BOJ can do: My post “What to Do When the World Desperately Wants to Lend Us Money” discusses this.

Empower the Fed: Give the Fed legal authority to buy as wide a range of assets as the Bank of Japan is allowed to.

Paul Romer on Charter Cities

As I mentioned on Twitter, I have often thought that if instead of going to graduate school in economics from 1983-1987, I had gone to graduate school just a few years later, I would have been a growth theorist, like my only slightly younger fellow Mankiw research assistant and coauthor David Weil, who was a graduate student in economics 1985-1990. The key event that made growth theory big in Economics were a few key papers (building on earlier work by Ken Arrow) by Robert Lucas and his brilliant student Paul Romer.

I copied these links from the wikipedia entries on Robert Lucas and Paul Romer.

- Lucas, Robert (1988). “On the Mechanics of Economic Development”. Journal of Monetary Economics22 (1): 3–42. DOI:10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7.

- Lucas, Robert (1990). “Why Doesn’t Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries”. American Economic Review80: 92–96. JSTOR2006549.

- “Endogenous Technological Change” (Journal of Political Economy, October 1990). Jstor link

- “Increasing Returns and Long Run Growth” (Journal of Political Economy, October 1986). Jstor link

- “Cake Eating, Chattering and Jumps: Existence Results for Variational Problems” (Econometrica 54, July 1986, pp. 897–908). Jstor link

So the timing of these breakthroughs was too late in my graduate school career for me to work on the new growth theory for my dissertation, but the new growth theory was the hot area by the time David Weil was choosing his dissertation topic.

Robert Lucas won the Nobel prize in Economics in 1995

for having developed and applied the hypothesis of rational expectations, and thereby having transformed macroeconomic analysis and deepened our understanding of economic policy

which would be enough accomplishment for any one career, so his work on growth theory is enough to make Robert Lucas a Saint of Economics with supererogatory merit that could be tapped into, if only there were a Pope for Economics.

But Paul Romer is well on his way to earning an even higher order of merit by effective thinking and advocacy, showing the way to go in practice toward a brighter future in which more countries are “Leveling Up, Making the Transition from Poor Country to Rich Country” (the title of my earlier post on economic growth). If you click the link under the picture at the top, you can see Paul Romer’s TED (Technology Entertainment Design) talk on Charter Cities.Please do. You will enjoy watching it as well as be enlightened. This is a great idea that can change the world. I guarantee that I will put this post on my next list of best “save-the world” posts, which will have a category for the best save-the-world ideas of other people that I have written a post about, as well as a lesser category for my own ideas.

Here is the link for the video again. And here is the link for the picture itself on the TED blog.

What to Do When the World Desperately Wants to Lend Us Money

Karl Smith has a recent post “Why is the US Government Still Collecting Taxes?: Should Lambs Lay Down with Lions Edition” arguing that we should be dramatically reducing tax collection because interest rates on government bonds are so low that, after correcting for inflation, every dollar in the national debt is shrinking over time. Karl’s post follows up on Ezra Klein’s post “The world desperately wants to lend us money,” and my grad school professor Larry Summers’s post “It’s time for governments to borrow more money.” Ezra and Larry want the government to pay ahead on things it is going to buy anyway and make other productive investments.

Larry, coming from his experience as Secretary of the Treasury makes a strong argument that the U.S. government should be borrowing long rather than short, in order to lock in amazingly low interest rates on long-term government bonds. Since the U.S. government’s position in relation to the bonds it has issued depends on what the Fed does as well as what the Treasury does, this argues against the Fed buying long-term government bonds when Larry’s argument says we should be selling long-term government bonds on net. Larry has convinced me by what he writes in “It’s time for governments to borrow more money.” The Fed should not be buying long-term government bonds.

But for the sake of stimulating the economy, the Fed needs to be buying large quantities of some type of asset. This is not just my view, implicit as a possibility in my post “Balance Sheet Monetary Policy: A Primer,” but the the official view of the Fed itself, since even the mostly stay-the-course policy the Fed announced at its last FOMC monetary policy making meeting involves buying large quantities of assets. (“Large” is less than “massive.”) So it is unfortunate that the legal authority of the Fed to buy assets is limited to a relatively narrow range of assets. See Mike Konczal’s interview with my undergraduate classmate Joseph Gagnon on the legal constraints the Fed faces. Short of buying foreign assets or otherwise going outside the Fed’s comfort zone, that probably means that the Fed should be buying mortgage-backed securities such as those issued by Fannie Mae. In general, when it uses balance-sheet monetary policy (what the press calls “quantitative easing”), the Fed should lean towards buying assets that have a high interest rate.

It is important to note that many of the objections to more vigorous use of balance sheet monetary policy in the U.S. are really objections to buying long-term Treasury bonds, not objections to buying other assets. Anytime you see an argument against balance sheet monetary policy, check whether it is an objection to buying any kind of asset or only to buying long-term Treasury bonds. And sometimes there are objections to buying Treasury bonds and other objections to buying mortgage-backed securities that even combined do not apply to other assets. So I wish the Fed had the kind of authority the Bank of Japan has to buy a wide range of assets, including commercial paper (CP), corporate bonds, exchange traded funds (ETF’s), and real estate investment trusts (REIT’s). I got this list of assets from the Bank of Japan’s own website on the range of assets it is buying. See also my post on how the Bank of Japan should use this authority quantitatively: “Future Heroes of Humanity and Heroes of Japan.”

Given the low interest rates the U.S. government is facing, even aside from stimulating the economy it should be spending more–mostly on things it would buy later anyway and other productive investments. On stimulating the economy, my proposal of Federal Lines of Credit is gaining some traction: you can see my posts on what Brad DeLong and Joshua Hausman and Bill Greider have to say recently, as well as what Reihan Salam said early on. In what I write myself on Federal Lines of Credit, including the academic paper “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy” that I flag at the sidebar, I emphasize the importance of not ultimately adding too much to the national debt as it will stand, say ten years from now. This is actually consistent with saying that the government shouldbe spending money now on things the government is going to spend money on sooner or later anyway, regardless of which party is in power, such as maintenance of military assets and stores, and the government should be spending money now on things that will add to the productivity of the economy so much that they will generate more than enough tax revenue to pay for themselves.