Gary: My point was a simple one: when someone like Seth goes after my reporting, they have to get their facts straight. Credibility is everything in this business, which is why Seth was trying so hard to undermine mine. My reason for not taking him seriously is he couldn’t get his facts straight and his take on science is, well, let us just say ill-formed. It’s not his fault because no one ever taught him (it seems to be particularly absent at the U.W., where he got his masters, but that might be my own issue.)

For example, let’s talk about the kind of mistake I worry about because it's egregious and embarrassing and any journalist who makes this kind of error must, first, publicly apologize and then find a different career. In my book (and in the 2011 NYT Magazine article that preceded it) I noted that fewer than a dozen human trials were being funded “that might identify what happens when we consume sugar or high-fructose corn syrup for years, and at what level of consumption we incur a problem.” These would be trials that might vaguely teach us something researchers working in this field don’t already know. Now the NYT Magazine would have fact-checked this closely back in 2011 and I remember asking my fact-checker to do it again, so this was surprising to me that I could screw this up, let alone as egregiously as Seth suggested.

Seth goes to clinicaltrials.gov, types in “sucrose OR fructose” as search terms and comes up with 450-plus hits of which 79 might be on-going in the U.S. at the time. So now I’ve seriously done our government a disservice and readers: I said less than a dozen. Looks like I was off by almost an order of magnitude, and Seth lets me have it in full sarcasm mode.

I just re-did Seth’s exercise and you can do it, too. It will take maybe 20 minutes. I typed in “sucrose OR fructose” as search terms in clinicaltrials.gov, and then went through the first 100 of the 539 hits that came up. Maybe two of the 100 at most were relevant to the question we want answered—long term sucrose consumption and our health—and arguably only one. Virtually all the rest, as you can see if you do this yourself, were on subjects in which the word “sucrose” appears -- most often for using sucrose as a pain reliever for babies or in studies of "iron sucrose" whatever that is. Seth didn't see the need to do this kind of basic exercise. (When you're trying to publicly assassinate someone's character, apparently you don't want to waste time doing your homework).

So do this yourself: go through some subset of all the hits that come up with those search terms – you can ignore whether they're ongoing—and count up how many are relevant to sugar consumption and chronic disease risk. That’s the issue this book is about. As I said, it should take you all of 20 minutes to get a feel for whether we’re talking hundreds, many dozens, or fewer than a dozen as I wrote. Think of it as calibrating Seth’s reporting and research skills, which is what I have always had to do with the academic researchers in this nutrition business. If they can get simple things so very wrong, what’s the likelihood they get the complex things right? Particularly in a case like this when their reason for existence is to demonstrate that someone else gets the simple things wrong.

Regarding the points below, I’ll get to them shortly.

Your evocation of Yudkin, though, reminded me of an interesting aspect of all this. For starters while I think Yudkin got sugar mostly right and arguably described metabolic syndrome twenty years before Reaven did, Yudkin also made a terrible mistake, which I discussed in GCBC. He insisted that low-carbohydrate diets work merely by cutting calories and he did so on the basis of two small ill-conceived experiments. He wrote two papers on it which the establishment thinkers then quoted as evidence to support their views. I did not mention this in TCAS, because it just wasn’t relevant although maybe I should have, as they are evidence that Yudkin could get things wrong. One way or the other, Yudkin got some stuff right, for which he gets credit, and some stuff wrong which I mention when relevant. Newburgh, too, turns out to have published two papers around 1920 on the efficacy of a very low carb, high fat diet for diabetes — a ketogenic diet, in effect, aka Atkins. In that he was almost a century ahead of his time, although it went nowhere. I didn’t know this when I wrote GCBC and it’s going to complicate my next book because having spent three books blaming Newburgh for the energy balance nonsense, I’m going to have to point out that he wasn’t always wrong. In this case, dietary therapy for diabetes, he got it right. The point is sometimes folks get things wrong and sometimes they get it right and it’s the author’s judgement how to treat these and why. Einstein famously didn’t like quantum physics and it gets brought up a lot — God doesn’t play dice and all that… — but it doesn’t mean he got relativity wrong. In a book on relativity, a science historian might not mention Einstein’s feelings about quantum physics because they might not be relevant. Context is everything.

If you go back and reread my epilog of GCBC, I evoke the philosopher of science Robert Merton making this point:

In science, as Merton noted, progress is only made by first establishing whether one’s predecessors have erred or “have stopped before tracking down the implications of their results or have passed over in their work what is there to be seen by the fresh eye of another.”

That is, in effect, what I did in this book. If I’m right, no one got it 100 percent right and so often what I was doing was pointing out what others had passed over in their work or neglected to interpret fully because they were trapped in a particular perspective and I wasn’t. So Atkins, for instance, got much of this right for the time and deserves considerable credit, but he didn’t get it all and he got a lot of things wrong. Same with Yudkin. And Bauer and Pennington and all the rest. I took out what I thought was right and directed our attention to it and neglected to repeat what I thought was wrong or the particular authors being trapped in their paradigms. That is what I perceived my job to be, and I put in that Merton quote as a reminder at the end.

You can think of what I did and what Seth did as antipodal approaches. Think of it as a murder case, for instance, in which investigators have different ideas who the murderer is - say, suspect A and suspect B. Most investigators and the media think it’s A and they want to rush to judgment. But one investigator — the intrepid inspector Taubes -- thinks its B. So he goes through all the evidence and says, look, B is always at the scene of the crime and never has an alibi and there’s always at least some evidence implicating him. And the others say, yes, but so is A. The job of the investigator who thinks its B, our friend inspector Taubes, is not to rule out A, although would be nice if it could be done, but to convince his many colleagues that B is a suspect and has to be considered seriously. Maybe he should even be the prime suspect, as I’m saying in the sugar book. Seth sees it as his job to point out every time I don’t mention that A was also implicated. I disagree that it was my job. So in GCBC, I say this in the introduction:

By critically examining the research that led to the prevailing wisdom of nutrition and health, this book may appear to be one-sided, but only in that it presents a side that is not often voiced publicly. Since the 1970s, the belief that saturated fat causes heart disease and perhaps other chronic diseases has been justified by a series of expert reports – from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Surgeon General’s Office, the National Academy of Sciences and the Department of Health in the U.K., among others. These reports present the evidence in support of this diet-heart hypothesis and mostly omit the evidence in contradiction. This makes for a very compelling case, but it is not how science is best served. It is a technique used to its greatest advantage by trial lawyers, who assume correctly that the most persuasive case to a jury is one that presents only one side of a story. The legal system, however, assures that judge and jury hear both sides by requiring the presence of competing attorneys to present the other side.

So what Seth is often doing in his critiques is saying, look this evidence that you say implicates suspect B also implicates suspect A, and you don’t say that. My counter argument is that 1) often I do — as I’ll discuss about a few of your points below — and Seth conveniently ignores it (glass house phenomena) and 2), my job, as I acknowledge in introductions to both books, is to present the case for suspect B. As I told Seth when we first exchanged e-mails, the first draft of GCBC was 400,000 words long and unfinished. My editor, bless his heart, read the whole thing because I was wondering if we could cut it into two books. He said, no, and then we got to work shortening it. His primary advice was that I typically gave multiple perspectives for every point: first the conventional wisdom, then the reason why the conventional wisdom was wrong, then the response of the establishment scientists to the evidence suggesting the CW was wrong, and then why that response was wrong. My editor said cut out the last two levels, and you can address those in the Q&A period of the lectures you’ll be giving on this topic. And that’s what I mostly did. Many of the mistakes made — specifically with references and citations — came about because of this process of cutting the manuscript in half. Much of what Seth accuses me of leaving out are simply judgment calls. Is it up to me to present the evidence for suspect A or reiterate why suspect A is being rushed to judgment, when my job in limited space is to argue that suspect B is very much a suspect, if not the prime suspect?

In the case of the sugar book, the title and author’s note state what the book is about. The last sentence of the author’s note is this: “If this were a criminal case, The Case Against Sugar would be the argument for the prosecution.” Seth and you seem to think I should be presenting the defense case for them as well. Ironically, often I do — and I’ve been criticized for that by some of my allies in the anti-sugar crowd -- but not always.

Here goes:

Point one: This is about the 1907 BMJ report on the diabetes in the tropics issue. After the quotes that Seth thinks I should have used, Seth concludes:

If we take the whole of the text into account, we find that these Bengali gentlemen not only consume starches and pulses, but also heavy fatty foods, and they consume it all in excess. Additionally, they don’t like to exercise according to these physicians. Might these lifestyle factors play a role in diabetes? Moreover, the physicians themselves make it clear that they do not think sugar and carbs cause diabetes since diabetes can also be present in those that do not eat carbs and be absent in those that consume a lot of carbs. If these physicians thought carbs promoted the development of diabetes they would not be prescribing diets that included honey, flour, rice, sweets, and wine in the treatment diets. Why doesn’t Taubes mention this?

But Taubes does, and at length. Here’s what I wrote on page 99 in TCAS, after the quotation from the conference:

What was unclear was whether the dietary trigger of diabetes was all carbohydrates, just refined grains (white rice and white flour among them) and sugars, sugars alone, perhaps gluttony itself, or even some other factor that predisposed the well-to-do to diabetes and protected the poor. From the discussion at the British Medical Association meeting, it was apparent that poor laborers could live on carbohydrate- rich diets without getting diabetes, whereas well-to-do Indians (and even affluent Chinese and Egyptians, as was noted by physicians at the conference) who lived on carbohydrate-rich diets easily succumbed to diabetes and seemed to be doing so at ever- increasing rates. What was the difference in their diet and lifestyle? “Unless the unknown cause of diabetes is present,” wrote Allen, “a person may eat gluttonously of carbohydrate all his life and never have diabetes.” Some of the physicians at the British meeting had suggested this unknown cause was the mental stress or “nervous strain” of the life of a professional—a doctor or a lawyer— compared with the relatively simple life of a laborer (as the British physician Benjamin Ward Richardson had suggested as a cause of diabetes in his 1876 book, Diseases of Modern Life); others suggested it was the idle life led by the wealthy and their disdain of physical activity that brought on the disease. Still others thought it was gluttony, or maybe alcohol. Sugar itself, as Allen noted, was consistently raised as a possibility.

In the immortal words of our former president, “Come on, man…” Does that not make exactly the point?

Point two:

First Seth debates my use of the phrase “singularly compelling.” What I was referring to was precisely what I quoted:

“This definite incrimination of the principal carbohydrate foods,” Allen wrote, “is, therefore, free from preconceived chemical ideas, and is based, if not on pure accident, on pure clinical observation.”

I suppose Seth has an argument that I’m giving this observation too much emphasis to say “singularly compelling” but it’s only an opinion. That said, I never say Allen believed unequivocally that sugar was the cause of diabetes or that their views weren’t muddy, as you describe them. I say his textbook included a “lengthy discussion” and “he believed it had to be discussed for the obvious reason: “The consumption of sugar is undoubtedly increasing,” wrote Allen. “It is generally recognized that diabetes is increasing, and to a considerable extent, its incidence is greatest among the races and the classes of society that consume [the] most sugar.”

And then I discuss his discussion. Including this:

Allen divided the European authorities into three schools of thought on a possibly causal relationship between sugar and diabetes. Some, like the German Carl von Noorden, author of several multi-volume textbooks on diabetes and disorders of metabolism and nutrition, rejected the idea outright; some, like the German internist Bernhard Naunyn (whom Joslin had visited as a young physician to learn about the disease), thought the evidence that sugar caused diabetes was ambiguous. These physicians wouldn’t blame sugar for actually causing diabetes, but did concede, wrote Allen, that “large quantities of sweet foods and the maltose of beer” favored the onset of the disease. Others, most notably the French authority Raphaël Lépine, were convinced of the causal role of sugar, and mentioned as evidence that diabetes was suspiciously common among laborers in sugar factories.

As Allen noted, however, what physicians said about sugar and diabetes and how they acted were often disconnected (as is still the case today): The majority of these authorities seemed to think that sugar had little or no role in actually causing the disease, although they were “open to accusations against sugar” when it came to the possibility that it exacerbated diabetic complications. Virtually all these physicians, including these same skeptical authorities, told their diabetic patients not to eat sugar, suggesting that they did indeed think sugar was harmful. “The practice of the medical profession is wholly affirmative” of this idea, Allen wrote. If sugar could make diabetes worse, he noted, which was implied by this near-universal restriction of sugar in the diabetic diet, then the possibility surely existed that it could cause the disease to appear in individuals who might otherwise seem healthy.

What Seth does and you imply is that because I used the phrase “singularly compelling” in one context, that meant that I was implying Allen had embraced this thinking wholeheartedly. And then you ignore everything else I wrote about Allen’s discussion. Again there seems to be a glass-house problem here. What Seth says I leave out seems very much like the discussion I actually had, although my version is more complete. You can actually get Allen’s book on google books and fact check this one yourself.

Point three.

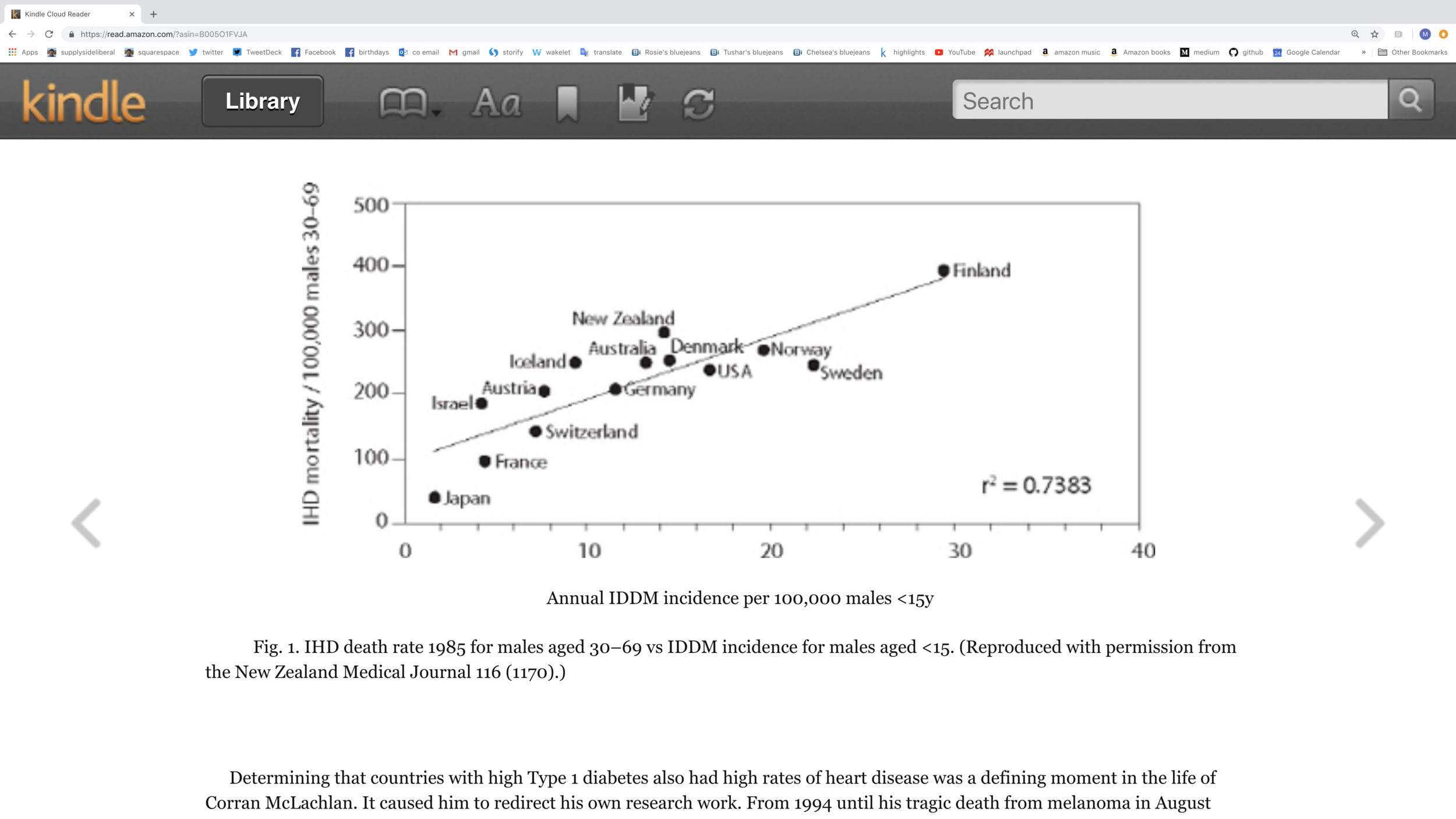

This is Emerson and Larimore. I’ve attached this paper. You can decide for yourself whether or not they thought sugar was a prime suspect or just a proxy for excess calories of all types. I’ve also attached a paper by Mills in 1930 citing Emerson and Larimore as the source of the argument that sugar causes diabetes. If you’d like I could dig out my copies of the early editions of Joslin’s diabetes to see if he makes the same point but as I say in GCBC, Joslin also cited Mills. That said, I suppose you could argue that Emerson and Larimore only considered sugar a prime suspect along with “greater abundance or superalimentation”, and not the prime suspect as I wrote and you’d have a good argument. But the only charts they present in this section are of sugar consumption and here’s their section head for their discussion of the effect of food on diabetes:

DEATH RATES FROM DIABETES IN RELATION TO VARIATION IN PER CAPITA CONSUMPTION OF FOOD, PARTICULARLY SUGAR

Again, I’d say it’s a judgment call and while Seth’s take that Emerson and Larrimore also believed that obesity itself was a cause (and so this superalimentation thing) is reasonable, it’s the defense attorney’s case, not the prosecutor’s.

Point four.

Seth is just showing either his ignorance here or his refusal to actually read these papers closely. Unfortunately, his quote comes from a paper Bauer wrote with an American, Silver, in 1931 and I only have that in hard copy now in bins in my attic. I’m going to assume though that what Bauer and Silver meant by “endocrine dysregulation” is what Bauer meant in his 1941 review article by “endocrine disturbance” (page 985). These are cases “in which obesity develops as a result of a tumor or other pathologic process in one of the endocrine glands.” It was one of the problems with how endocrinology was studied in relationship to obesity. The authorities specialized in specific glands and the review articles were written about those glands—the site of the hormone secretion, not the target cells and tissues. So Bauer was differentiating between a structural abnormality or disease in the glands (see highlighted section page 987)—the “endocrine disturbance”—and the general tendency for fat accumulation which operates through the endocrine glands (as well as well as the nervous system). Just read the article and you’ll see. If you have further questions, I’ll answer them.

That said, Seth is absolutely right that Bauer said the diet should be restricted in calories. As I point out repeatedly in my books (and in the version of my Why We Get Fat lecture that takes the historical perspective), though, it wasn’t until 1960 and the invention of the radioimmunoassay that endocrinologists could establish insulin as the regulator of fat accumulation and so carbohydrates as the likely trigger of excess fat accumulation. Hence, the dietary implications of this hormonal/regulatory hypothesis took until the 1960s. It would have been nice if Bauer was pushing carb restriction, and I suppose I could have put in a footnote to the effect that even though he didn’t think “overalimentation” was the cause, he still pushed underalimentation as a treatment. Still, what Seth is arguing here is bizarrely wrong.

Enjoy Bauer’s article, he was a smart guy.

Point five.

Seth has got me on this one. What he doesn’t say, though, (glass houses), is that his ellipses encompass almost an entire page. I’ve attached the article. It’s page 310. He implies that the sentence about caloric balance comes right before the sentence about attentive consideration. You decide if I did Wilder an injustice. Yes, Wilder also was a prisoner of his context. What was important to me was Wilder’s thoughts on Bauer and the lipophilia (hormonal/endocrine) hypothesis, not the fact that he, too, was confusing the correlation of positive energy balance with the cause. (Or maybe felt, as people often do, that he had to say it was all about calories just so folks wouldn’t get mad at him and stop reading.) Anyway, read Wilder’s discussion and you tell me whether I did him a disservice. Either way, it’s another judgment call, very much like the Bauer undereating recommendation. I could go through and include every point in which these folks agree with the CW and then discuss when they don’t, but I’d end up with a 400,000 page unreadable book.

Point six.

This is Seth going on about my treatment of Rony. Here is what he quotes me saying and then what he says:

By 1940, the Northwestern University endocrinologist Hugo Rony, in the first academic treatise written on obesity in the United States, was asserting that the hypothesis was “more or less fully accepted” by the European authorities. Then it virtually vanished.

I think it’s important to note a few things here. First, Rony did not claim it was accepted by “the European authorities” (Taubes also makes this mistake in GCBC by stating it was accepted “in Europe”), but rather that it was accepted in Germany. Minor point, but worth mentioning because Taubes clearly expands the acceptance from one country to an entire continent to make it seem more legitimate. Second, Rony also mentions a few things immediately following the “more or less fully accepted” quote that are less than charitable to the theory. Notably on page 174,

Seth has me on the Europe vs. Germany issue. Although as he says, it’s a minor point. Here’s the full quote (page 173-4 in Rony’s book):

The subsequent discovery that normal fat tissue is the site of considerable metabolic activity-especially glycogen transformation (page 41)—was looked upon by many as strongly supporting the theory, which is now more or less fully accepted, chiefly in Germany, by a number of leading investigators of metabolic diseases (Umber, Zondek, Richter, Falta, Bauer, Lichtwitz, etc.)

Because Bauer and Falta are Austrians, I figured I could say Europe. Sue me. Virtually all the meaningful work was being done in Germany and Austria in any case.

As for Seth’s other argument:

Second, Rony also mentions a few things immediately following the “more or less fully accepted” quote that are less than charitable to the theory

Yes, Rony was a good scientist. I make the point that they tended to be, the Europeans, pre-WW2. He didn’t see his job as selling anyone on the theory but discussing the evidence openly. Reading his book was refreshing in that sense. The fact that fatty acid mobilization is not slowed in obesity is a critical finding in the field and led Pennington to his theories and is still argued today. This was one reason why Rony evoked the terms dynamic and static phases of obesity. And it’s a long conversation, but the fact that Rony discussed the evidence that was absent in confirming the theory does not mean he didn’t think the totality of the evidence supported it.

Seth gives a link for the Rony book on line. Read it yourself and tell me whether you think he believes it’s likely to be right.

Point seven

This one took me a bit to figure out exactly what the problem was. He’s saying Trowell never said anything about the native populations “high-fat diet.” I don’t suppose Trowell ever did. The point is he was based in Kenya and the native populations he was discussing were pastoralists, primarily the Masai. They ate a high-fat diet. The point about no shortage of food was that Trowell commented they always had enough to feed their pets afterward. (Although now that I look at that quote, I suppose I should have said usually had enough, because of that clause “almost invariably, except in times of scarcity”.) Here’s the relevant paragraph from Galton’s The Truth About Fiber, which is the source of the Trowell quote:

He had noticed, too, that when he was entertained in African homes, almost invariably, except in times of scarcity, food was left at the end of the meal and fed to domestic pets.

So, yes, the “high-fat” was me filling in the details from what I knew about the pastoralist diet in Kenya. Seth may be right that I jumped to conclusions. Typically when nutritionists were talking about Kenyan populations it was the Masai or another pastoralist population whose name I forget at the moment, but there may have been many more that were agriculturalists.

His point that Trowell thought this was a calorie issue is just irrelevant. Everyone did (outside of those pesky Germans and Austrians) and that’s not why Trowell was in the book. It’s an irrelevant comment. Although Seth is right, I often used ellipses to simplify things, which means cutting out parts of the quote that are irrelevant to the point I want to make. While Trowell may have thought the problem was getting the Africans to eat enough to get fat; I thought the observation of interest was that they couldn’t figure out how to make them fat, even though they seemed to have plenty of food. Seth is saying Trowell thinks its suspect A. I’m saying the evidence points to suspect B and pointing out that Trowell thought like Seth just complicates the text. Make sense?

I hope this helps. Once again I did this quickly.

Miles: This is fascinating! What you have written in this email is precisely the sort of thing I'd love to have on my blog.

Gary: …I do think you should take the time and read the articles. … One of the lessons in all this is you cannot trust anyone, not the authorities, not the self-appointed authorities (specifically Seth in this case, but me, too). …

… Seth tries so hard to assassinate my character …

Gary: I've been noticing other folks recently tweeting Seth's attack (I had to think of what the write word is there) on TCAS and my work. As such, that and the Wired article and some of Guyenet's latest, have me thinking that I should do my own blog post on all of this someday -- a discourse on the difference between blogging, web journalism and the journalism I grew up practicing (similar to science in that you really want to know, as do your editors, that what you think is so and hence what you write is really true). If I ever make time to do that, it would be easier for me if your blog post acknowledges my input and that you were in touch with me and what I wrote back. That might be easier for you to write in any case. If you do that and then I end up making some of the same points, I won't look like I'm plagiarizing you. I don't know how far along you are so how much of a pain this is for you, but I'd appreciate it if this works for you. If not, I'll understand and write around it. (Assuming, as I said, I ever get to doing this.)

Let me know what you think and thanks for considering.

Miles: Wonderful! I agree with your tentative decision not to just brush off Seth's attack as something that would remain mostly unknown if you don't talk about. I can just report again that more than one person mentioned Guyenet and Seth, and of course if you get to Guyenet you see his flagging of Seth.

Don't miss these other posts on diet and health and on fighting obesity:

I. The Basics

II. Sugar as a Slow Poison

III. Anti-Cancer Eating

IV. Eating Tips

V. Calories In/Calories Out

VI. Wonkish

VIII. Debates about Particular Foods and about Exercise

IX. Gary Taubes

X. Twitter Discussions

XI. On My Interest in Diet and Health

See the last section of "Five Books That Have Changed My Life" and the podcast "Miles Kimball Explains to Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal Why Losing Weight Is Like Defeating Inflation." If you want to know how I got interested in diet and health and fighting obesity and a little more about my own experience with weight gain and weight loss, see “Diana Kimball: Listening Creates Possibilities” and my post "A Barycentric Autobiography.