John Locke: The Public Good

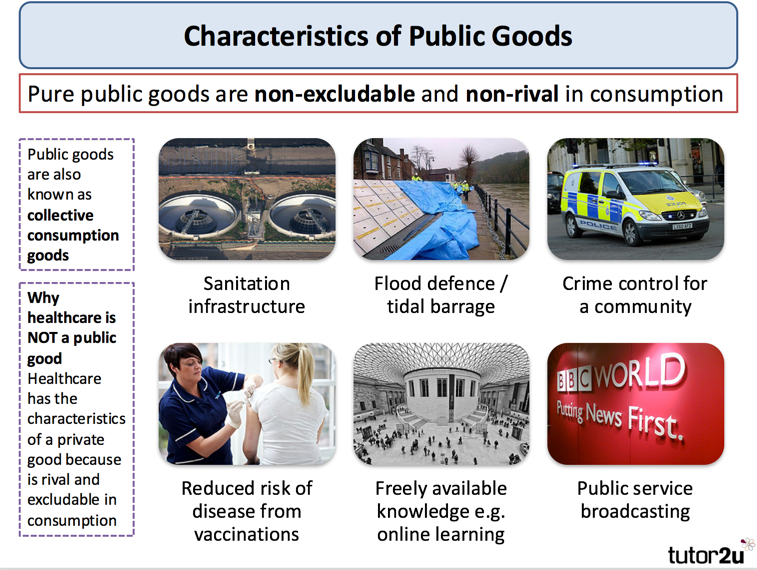

Image source. On the claim above about healthcare, see a counterpoint in the post “Health Economics”: one’s psychic enjoyment of not having other people in the nation be in bad shape is nonexcludable and nonrival.

Paul Samuelson laid out the standard theory of public goods that is now taught to all economics students in their first economics class. Centuries earlier, John Locke used the phrase “the public good” in a way that doesn’t make its meaning fully clear. I noticed because in “The Social Contract According to John Locke” I say:

John Locke's version of social contract theory is striking in saying that the only right people give up in order to enter into civil society and its benefits is the right to punish other people for violating rights. No other rights are given up, only the right be be a vigilante.

This accords with the drift of most of John Locke’s “2d Treatise on Government: “Of Civil Government, but in Sections 128-131 (in Chapter IX, “Of the Ends of Political Society and Government”) he adds another right that people give up. Let me slice this passage into two: first the part that is in line with my paragraph quoted above and then the part that seems to say something different. Here is the slice about giving up the right to be a vigilante and to do one’s part in authorized posses:

§. 128. For in the state of nature, to omit the liberty he has of innocent delights, a man has two powers. … The other power a man has in the state of nature, is the power to punish the crimes committed against that law. … these he gives up, when he joins in a private, if I may so call it, or particular politic society, and incorporates into any commonwealth, separate from the rest of mankind. …

§. 130. Secondly, The power of punishing he wholly gives up, and engages his natural force, (which he might before employ in the execution of the law of nature, by his own single authority, as he thought fit) to assist the executive power of the society, as the law thereof shall require: for being now in a new state, wherein he is to enjoy … the … assistance … of others in the same community, as well as protection from its whole strength; he is to part also with as much of his natural liberty, in providing for himself, as the … safety of the society shall require; which is not only necessary, but just, since the other members of the society do the like.

§. 131. … but is obliged to secure every one’s property, by providing against those three defects above mentioned, that made the state of nature so unsafe and uneasy. And so whoever has the legislative or supreme power of any commonwealth, is bound to govern by established standing laws, promulgated and known to the people, and not by extemporary decrees; by indifferent and upright judges, who are to decide controversies by those laws; and to employ the force of the community at home, only in the execution of such laws, or abroad to prevent or redress foreign injuries, and secure the community from inroads and invasion. And all this to be directed to no other end, but the peace [and] safety, … of the people.

Here is the slice about being subject to a legislature for a wider range of purposes:

§. 128. For in the state of nature, to omit the liberty he has of innocent delights, a man has two powers. The first is to do whatsoever he thinks fit for the preservation of himself, and others within the permission of the law of nature: by which law, common to them all, he and all the rest of mankind are one community, make up one society, distinct from all other creatures. And were it not for the corruption and viciousness of degenerate men, there would be no need of any other; no necessity that men should separate from this great and natural community, and by positive agreements combine into smaller and divided associations. … Both these he gives up, when he joins in a private, if I may so call it, or particular politic society, and incorporates into any commonwealth, separate from the rest of mankind.

§. 129. The first power, viz. of doing whatsoever be thought for the preservation of himself, and the rest of mankind, he gives up to be regulated by laws made by the society, so far forth as the preservation of himself, and the rest of that society shall require; which laws of the society in many things confine the liberty he had by the law of nature.

§. 130. … for being now in a new state, wherein he is to enjoy many conveniences from the labour, assistance, and society of others in the same community, … he is to part also with as much of his natural liberty, in providing for himself, as the good prosperity … of the society shall require; which is not only necessary, but just, since the other members of the society do the like.

§. 131. But though men, when they enter into society, give up the equality, liberty, and executive power they had in the state of nature, into the hands of the society, to be so far disposed of by the legislative, as the good of the society shall require; yet it being only with an intention in every one the better to preserve himself, his liberty and property; (for no rational creature can be supposed to change his condition with an intention to be worse) the power of the society, or legislative constituted by them, can never be supposed to extend farther than the common good; … And so whoever has the legislative or supreme power of any commonwealth, is bound to govern by established standing laws, promulgated and known to the people, and not by extemporary decrees; by indifferent and upright judges, who are to decide controversies by those laws; and to employ the force of the community at home, only in the execution of such laws, … And all this to be directed to no other end, but the … public good of the people.

These two slices give very different pictures of the state: the first a mutual defense agreement, the second a mutual improvement association. Of course, the passage as a whole admits of the interpretation that by “the public good,” John Locke is only referring to peace and safety: national defense and control of crimes against the law of nature can certainly be considered “the public good.” The question is whether they are the only “public good” John Locke is referring to. The polar opposite interpretation is that John Locke was referring to more or less the set of things that Paul Samuelson later on called “public goods.”

My interpretation is that John Locke primarily wanted to emphasize national defense and control of crimes against the law of nature, but he didn’t want to make his theory implausible by entirely excluding the legitimacy of the state using its power for the sake of other public goods. But this passage does not make clear what, if any, other public goods he thinks the state could legitimately deploy its power for.

For links to other John Locke posts, see these John Locke aggregator posts: