Peter Conti-Brown on the Incompleteness of the Law

“Law in practice differs in sometimes surprising, contradictory ways from law on the books. The argument is not that law is irrelevant; it is that the law is incomplete.”

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

“Law in practice differs in sometimes surprising, contradictory ways from law on the books. The argument is not that law is irrelevant; it is that the law is incomplete.”

Update, June 5, 2019: On this topic, be sure to check out this more recent blog post: “Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball—Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide.” The paper of that title expands on the idea that, except for the concern about disintermediation or “debanking,” it is quite speculative to think we are anywhere close to an effective lower bound on interest rates. An effective lower bound other than a concern about debanking would require essentially the conversion of the entire national debt into paper currency. For the US, that would require the storage of something on the order of $20 trillion as paper currency, which is a Herculean task. Long before that, the Fed would be worried about the consequences to the banking system. It is those worries about the consequences of deep negative rates for the banking system to form the effective lower bound.

Once the convenience of electronic money for a large fraction of transactions (especially large transactions and business to business transactions) is recognized, the key to enforcing the zero lower bound in many stark formal models that assume a traditional paper currency policy is the emergence of some equivalent to money market mutual funds backed by paper currency. That is, in the models, it is the “electrification” of paper currency by funds that have paper currency as their key asset and an electronic means of exchange as their key liability that creates the zero lower bound.

But in the real world, the business model for money market mutual funds backed by paper currency is not that promising, given the danger that the government is likely to be annoyed at such funds thwarting a negative interest rate policy, and is likely to act against such funds. Some things are relatively easy to do in opposition to a government, but setting up a money market mutual fund with access to the electronic payments system is not one of them. Even Bitcoin is much more vulnerable to any government action against it than some of its enthusiasts think. And something trying to look as much as possible like a regular money market mutual fund, but backed by paper currency is much more vulnerable to the government than Bitcoin.

Thus, when a central bank lowers its target rate and interest rate on reserves, it is not large scale paper currency storage by the equivalent of money market mutual funds backed by paper currency that is the first symptom of the effective lower bound kicking in, but expanded small-scale storage of paper currency by households and businesses keeping more of their liquid balances as paper currency instead of in bank accounts, or the fear by banks of such a shift into paper currency. That is, the first symptom of the effective lower bound kicking in is disintermediation or fear of disintermediation.

One can debate just how important banks are to the functioning of the economy, but given how much economic activity currently runs through banks, it seems likely that trying to move all of that economic activity outside of banks within too short a time period is likely to be disruptive. So sudden disintermediation is probably something to be avoided. And banks’ fear of households and businesses shifting toward small-scale paper currency storage is likely to lead them to cut deposit rates less than the extent to which other interest rates fall when the paper currency interest rate is kept at zero in a traditional paper currency policy. This could lead to a reduction in the net interest margins that are a mainstay of bank profits.

If banks are extremely well capitalized going into a period of negative interest rates (that is, with a lot of equity on the liability side of their balance sheets), a strain on bank profits and consequent effect on equity levels will have very little effect on the probability of insolvency. But if banks go into a period of negative interest rates with relatively low levels of equity, the strain on profits could lead to more serious undercapitalization, with a consequent heightened probability of insolvency. And low bank profits can be a political problem even in situations where they are not a serious economic problem at all.

One solution to the strain on bank profits and consequent reduced capitalization is to subsidize banks. This is the approach I discuss in “How to Handle Worries about the Effect of Negative Interest Rates on Bank Profits with Two-Tiered Interest-on-Reserves Policies.” But the other approach is to lower the paper currency interest rate, to avoid most of the problem of a profit squeeze on banks in the first place. That is the approach I discuss in “If a Central Bank Cuts All of Its Interest Rates, Including the Paper Currency Interest Rate, Negative Interest Rates are a Much Fiercer Animal.” In other words, if a central bank begins to see the particular strains on bank profits that are symptoms of the effective lower bound in action, it should consider eliminating the effective lower bound itself by lowering the paper currency interest rate, as discussed in “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”

Here are the two important folk sayings that have been falsely attributed to John Maynard Keynes:

Link to Wikipedia article on Lee Kuan Yew, who was Prime Minister of Singapore for 30 years

John Stuart Mill was more favorable to paternalism than many might think. (Since for his time, he was a Feminist, it might also be called maternalism.) As the surprising 10th paragraph of the “Introductory” to On Liberty indicates, he is willing to extend principles for the treatment of minor children to whole nations:

It is, perhaps, hardly necessary to say that this doctrine is meant to apply only to human beings in the maturity of their faculties. We are not speaking of children, or of young persons below the age which the law may fix as that of manhood or womanhood. Those who are still in a state to require being taken care of by others, must be protected against their own actions as well as against external injury. For the same reason, we may leave out of consideration those backward states of society in which the race itself may be considered as in its nonage. The early difficulties in the way of spontaneous progress are so great, that there is seldom any choice of means for overcoming them; and a ruler full of the spirit of improvement is warranted in the use of any expedients that will attain an end, perhaps otherwise unattainable. Despotism is a legitimate mode of government in dealing with barbarians, provided the end be their improvement, and the means justified by actually effecting that end. Liberty, as a principle, has no application to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being improved by free and equal discussion. Until then, there is nothing for them but implicit obedience to an Akbar or a Charlemagne, if they are so fortunate as to find one. But as soon as mankind have attained the capacity of being guided to their own improvement by conviction or persuasion (a period long since reached in all nations with whom we need here concern ourselves), compulsion, either in the direct form or in that of pains and penalties for non-compliance, is no longer admissible as a means to their own good, and justifiable only for the security of others.

Many have seen racism in this paragraph. But everyone who objected to George W. Bush’s optimism about nation-building and democracy-building in the Middle East is coming from a similar place. Only slightly more starkly, if the alternatives for a given nation are dictatorship or genocide, dictatorship is to be preferred. I don’t see those as the only two options very often, but I do think it might be common for the only realistic alternatives for a nation to be dictatorship, genocide, ethnic cleansing in the sense of forcible removal, or a long-lasting, expensive, controversial, foreign occupation.

Despite my leeriness about the end of the sentence this is in, I think John Stuart Mill is right in saying “The early difficulties in the way of spontaneous progress are so great, that there is seldom any choice of means for overcoming them.”

I often think of the difficulties that the leaders of China face. I have not been shy of criticizing them (1, 2), but I also recognize that there is no easy answer to the dilemmas they face. What would I do if I were in their shoes? I would allow freedom of speech and expression, freedom of the press and religion, and institute free elections at the local level quickly, but I would be afraid of free elections at the regional level for fear that would lead to civil war, and afraid that trying to have free national elections would lead to greater nationalism along the lines of Vladimir Putin in Russia. In “Why Thinking about China is the Key to a Free World,” I point to the paradox that since people love freedom, a benevolent dictatorship, to be benevolent, would have to give people freedom.

For improving the world we live in today, one of the most important tasks is figuring out what compromises are the right ones to make in getting from an unfree government to a free government without disaster along the way such as genocide or war. We must face the truth of what is possible and what is not–whatever that truth is–even when making decisions about freedom.

Today marks four years since my first post, “What is a Supply-Side Liberal?” I have had a tradition of anniversary posts:

The past year has been an intensely busy year for me in research, teaching and in looking for ways to get more leeway in relation to my time budget constraint. There are many activities I would in principle be glad to cut back on, but they turn out–in part by an important bit of economic logic–to be a subset of the activities especially crucial for getting paid. What I want to do more of is blogging–something I do for free. (I have been paid a meaningful amount as a Quartz columnist, but it is a very small fraction of what I earn from my regular salary.) So why do I put such a high priority on blogging? I gave an answer after a little over one year of blogging in “Why I Write.” Let me answer it now in terms of the reasons that keep me going, with no end in sight, after four years of blogging.

The main reason I blog is the hope of making a difference in the world. I have always expected that having any influence on economic policy would be very difficult. So I have been pleased at how well rewarded my efforts to forward negative interest rate policy as a monetary policy option have been. I realize that the stars may have specially aligned for negative interest rate policy. Other policy and individual choice areas may be harder to make a difference in. But I have faith that as long as one’s timeline is on the order of decades or generations, there is always great hope that the world can be diverted onto a significantly better path.

The second reason I blog is to express myself. This is closely related to what I wrote in “A Year in the Life of a Supply-Side Liberal”:

In the public arena, not having a blog, Twitter account, Facebook page or similar platform felt to me a little like being one of those ghosts in the movies who try to talk to their still-living friends and family, but find that their words are inaudible. Now I can talk back when I disagree with what I read in the Wall Street Journal at the breakfast table. Or I can add my two cents to an idea that I agree with.

There is a nuance now. Some days I have something I am dying to say. Other days, I think “I need to stay in the game by blogging regularly so that when I do have something I am dying to say, there will be readers there to hear it.” That is, I try to be dependable for my readers so that they will be there when I have an idea I really want to get out there. (According to the rules I have made up for myself, being dependable for my readers includes (a) having something new every day, even if it is just a link, (b) having a Sunday post on either religion or a key text like John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty (c) at least two other posts with some meat to them each week and (d) having the blog be visually appealing with several pictures every week to break up the words. Living up to that has not always been easy.)

The third reason I blog is the pleasure of all the relationships I have made online. Blog posts, their associated Facebook posts, and all the tweets I do have helped me get to know many people I otherwise wouldn’t, and to interact with people I already knew more than I otherwise would. It is great to feel connected to people. And those online connections often spill over into the rest of my life, whether in the academic sphere, the sphere of journalism, or the personal sphere. I had a chance on Monday to write about some of those online relationships in “Friends and Sparring Partners: The Skyline from My Corner of the Blogosphere.”

Someday I hope I can reap all of these rewards from blogging and have blogging figure into my merit raises as well. I get indications that blogging is a definite plus for recruiting of graduate students and recruiting of new professors, since for the growing fraction of economists who read blogs, it is attractive to go to a department that hosts a familiar blogger. There is great hope that someday economics departments will realize the value of blogging for recruiting and for the reputation of a department more generally for a simple reason. How positive economists are about blogs and blogging is strongly correlated with age. Generational replacement alone will make the attitude of the average working economist of the future much more positive toward blogs in the future than it is now. And already, the positive attitudes of many of the young toward blogs is what makes blogging so valuable for recruiting.

Sometimes blogging has been hard work. I have enmeshed myself in a motivational web that makes it easy to do that hard work despite the sacrifice that sometimes represents.

But blogging is also a lot of fun, and definitely rewarding on many levels. I even feel blogging has made me smarter than I otherwise would have been, because of all of the extra thinking it has led me to do. If you have had a fraction as much fun reading my blog as I have had writing it, I have been successful.

If several businesses got together and agreed to raise their prices, that would be an antitrust violation. But when people with something to sell get together and run to the government and successfully ask for a regulation that will raise their prices, people often see that as OK. That makes no sense. If a restraint of trade would be a bad thing done by private agreement, surely that restraint of trade is also a bad thing done by government at the point of a gun.

Of course, for most people, the big difference between a good and a bad restraint of trade is this:

Competition for thee; collusion for me.

That is, I hate competition that I have to face, but like competition for you that keeps prices down for me.

The standard argument against competition–when it is competition for me–is that (a) competition will lower quality because low-price, low-quality alternatives will be offered, and (b) these low quality offerings will have a bad spillover effect on people’s guesses about the quality of what I am selling. Notice that this is an all-purpose argument that can be used to justify almost any type of collusion.

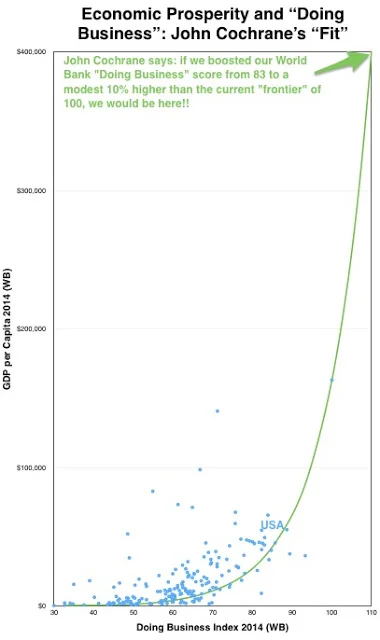

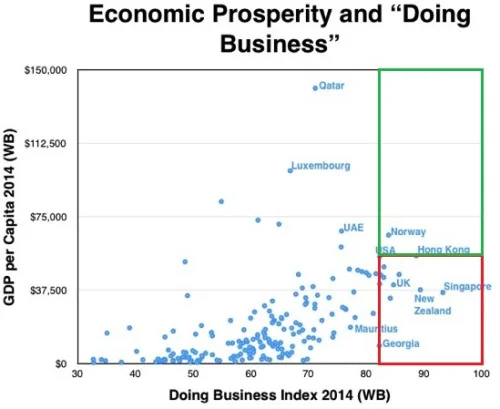

In his post “Dear John Cochrane, you are hurting the economists who care about you,” Matthew Martin distinguishes between reasonable and unreasonable arguments in favor of deregulation. Focusing narrowly on the “ease of doing business” rating for a cross-section of nations, Matthew contrasts John Cochrane’s rash extrapolation

with the fact that those nations with a greater ease of business than the US do not do any better than the US in GDP per capita:

Evan Soltas, in “Is Pro-Business Reform Pro-Growth?” drives home the point by considering cases in which a country made a big leap up in ease of doing business, finding that there is very little growth dividend. My reaction to Evan’s post is to think that the “ease of doing business measure,” while correlated with things that make a difference, particularly among countries with lower scores than the US, but does not itself capture the key things. When countries raise their “ease of doing business scores” it might be like colleges gaming their rankings once they have figured out the US News and World Report formula for the college rankings. It is hard to genuinely make things better. It is much easier to raise a score by gaming it. And the “ease of doing business” rating is prestigious enough for many countries to see it as worth gaming it to raise it.

What if some of the key types of deregulation that are especially important for economic growth don’t show up in the “ease of doing business” rating? To the extent doing them well is correlated with the “ease of doing business rating,” the “ease of doing business” rating could be a good indicator, but it would be a less good indicator when a country is only doing the things tallied in the “ease of doing business” rating without also doing the things often correlated with a greater “ease of doing business.”

As an example of thinking about the benefits of deregulation more carefully than John Cochrane, Matthew Martin links to Salim Furth’s Heritage Foundation report “Costly Mistakes: How Bad Policies Raise the Cost of Living.” Let me list 11 areas Salim points to as areas of harmful regulation (I didn’t understand his least important example, “cement production regulation”) in the order of how big Salim thinks the annual cost to the average family is, without regard to what level of government is involved; many of the biggest are perpetrated by state and local governments. Indeed, I have often thought that instead the overly broad use of the “interstate commerce” clause of the US Constitution to meddle in things that are far removed from interstate commerce, the Federal government should use the interstate commerce clause to prevents states and localities from strangling their economies and thereby the US economy with harmful regulation. It is good to defer to states and localities when they lean in the direction of freedom, not always so good to defer to states and localities when they strangle freedom.

All estimates of annual cost to the average family are from Salim Furth

When faced with the politics of such schemes, it is easy to get discouraged. But a journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step. One of the first steps toward getting rid of bad regulations is to call them out for the reflections of self-interest that they are, and refuse to let them hide behind prettified excuses. What is achievable in the medium-term is that whenever journalists write about any of these regulations, someone close to hand is ready and willing to be quoted about how selfish these regulations are.

Note: You might be interested in the related Storify story “Jonathan Portes, Brad DeLong and Noah Smith Set Me Straight When I Praise John Cochrane’s Shoddy OpEd.”

“The problem is that the standard account of Fed independence—the story of Ulysses and the sirens, of the dance hall and the spiked punch bowl—often doesn’t work. Sometimes politicians whip up popular sentiment in favor of taking away the punch bowl—precisely the opposite of what we expect in a democracy. Sometimes the central bankers make headlines not for being boring chaperones but for bailing out the financial system. And in every case the creaky, hundred-year-old Federal Reserve Act leaves a governance structure that makes it so we barely know who the chaperone is even supposed to be.

… I argue that each of the five elements of that standard account—that it is law that creates Fed independence; that the Fed is a monolithic “it,” or more often an all-powerful “he” or “she”; that only politicians attempt to influence Fed policy; that the Fed’s only relevant mission is price stability; and that the Fed makes purely technocratic decisions, devoid of value judgments—is wrong.”

Intelligent Economist: Top 100 Economics Blogs of 2016

Keeping up with my personal life, teaching, research, writing my own blog, and reading from the Wall Street Journal and the Economist plus varied articles that I see on Twitter leaves me much less time to read economics blogs than I would like. Still, there are some blogs that I read with some frequency. The Intelligent Economist’s list “Top 100 Economics Blogs of 2016″ gives me to think about the blogs in this list that bulk largest in my consciousness and correspondingly have the most influence on me. My emphasis in this post is on the bloggers themselves rather than their blogs. And as my title suggests, this is a very personal view (some might even say egocentric–see my confession in “The Egocentric Illusion).

I am mostly borrowing the fairly arbitrary order of the Intelligent Economist, but I have grouped people into “friends” and “sparring partners.” To make it into this post, a blogger had to be both in the Intelligent Economist’s list and someone who bulks large in my consciousness.

Noah Smith: Bloomberg View Economics

I was Noah’s principal dissertation advisor, but Noah was my advisor in starting my own blog. I am a great admirer of Noah’s vivid style, his wide-ranging command of ideas and his ability to penetrate to the heart of an issue. I analyzed Noah’s style in my post “Brio in Blog Posts” for the sake of my students, whom I asked to write close to 40 blog posts over a semester in my Monetary and Financial Theory class. There is very little daylight between Noah’s views and mine. In addition to his Bloomberg View columns, his own blog Noahpinion, and some popular Quartz columns coauthored with me (see for example #1 math, #4 econ PhD and #13 Minneapolis here), Noah has a hard-hitting series of guest posts on my blog about religion.

Narayana Kocherlakota: Bloomberg View Economics

One of the most pleasant surprises this year has been Narayana Kocherlakota’s full-speed-ahead emergence as a major blogger and tweeter, not long after he stepped down as President of the Minneapolis Fed. Narayana is a strong proponent of negative interest rates, though I am not aware of his having the negative interest rates for paper currency that are the linchpin of my proposal for eliminating the zero lower bound.

Other than reading his blog, Ben is too busy for me to have any meaningful interaction with him electronically, but I have known him a long time from NBER conferences, I had lunch with him twice at the Fed itself in the past few years (he made a habit of eating lunch in the Fed’s regular cafeteria), saw him when he came to speak at the University of Michigan, and expect to see him at a Brookings conference next month. You can see my disagreement with him about negative interest rate policy in “Ezra Klein Interviews Ben Bernanke about Miles Kimball’s Proposal to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound.” I have declared Ben Bernanke a hero on many occasions for his actions mitigating the harm from the Financial Crisis of 2008 and making the Great Recession less severe than it might have been. However much better monetary policy might have been than what Ben achieved, I have some appreciation for how hard it is to figure out in real time what needs to be done in a crisis and how hard it is to persuade others in real time to support the actions that are needed. Ben did admirably in a tough situation.

Tyler Cowen: Marginal Revolution

Tyler Cowen and I were graduate school classmates at Harvard. He wrote about our time in graduate school here. I appreciate Tyler’s thoughtful attention to the supply side of the economy in his blog, and I love the metaphor of a “Marginal Revolution,” which I play off of in my 2d anniversary post “Three Revolutions.” I have greatly admired Tyler’s longer pieces (some published in other venues), such as “The Inequality that Matters.” My favorite of Tyler’s recent posts is “What are the core differences between Republicans and Democrats?”

Alex Tabarrok: Marginal Revolution

I greatly appreciate Alex Tabarrok’s levelheaded commentary on a wide range of issues. And I like his emphasis on the importance of ideas for economic growth, very well expressed in his TED talk “How Ideas Trump Crises.”

Right before I started blogging, I remember Bob Hall telling me that Mark Thoma’s blog “Economist’s View” was his one-stop shop for blogs to read. In addition to writing his own posts, Mark Thoma is the premier aggregator of economics blog posts in the world. This is a wonderful public good.

Brad DeLong was a year or two ahead of me in graduate school at Harvard, and our research interests align closely enough that we have kept track of each other over the years. When Brad came to give a seminar at the University of Michigan a few years ago, I was struck by a powerful case of blog envy. That was one of the big things that made me realize that I needed to start a blog of my own. Brad and I are in agreement about most things–something I know because when he disagrees with me, he is quick to note what an exception that is. Brad digs deep in his analysis. For example I admire his post “Mr. Piketty and the “Neoclassicists”: A Suggested Interpretation.” But Brad is also willing to be an attack dog when he sees someone saying something he considers not only wrong, but dangerously wrong. Brad is someone I especially wish I could get to comment in depth on a wider range of the proposals I have made.

Scott Sumner: The Money Illusion

When I was just about to start blogging, Noah Smith told me that Nominal GDP Level Targeting was very big in the blogosphere, and that I should write about it. I finally did in “Optimal Monetary Policy: Could the Next Big Idea Come from the Blogosphere?” Scott Sumner has changed a lot of minds with his advocacy of Nominal GDP Level Targeting. I have met many young and not-so-young economists, in and out of central banks, who have spoken enthusiastically of Nominal GDP Level targeting. That wouldn’t have happened without Scott. My emphasis is different from Scott’s (emphasizing negative interest rate policy), but we are in fundamental agreement on the substance, as you can see in “Miles Kimball and Scott Sumner: Monetary Policy, the Zero Lower Bound and Madison, Wisconsin.” In negative interest rate policy, Scott was an early proponent of a negative interest rate on reserves–a policy he ably defends in “The Media’s Blind Spot: Negative Interest on Reserves.” When he touches on topics outside of monetary policy, Scott is concerned about supply-side reform along the same lines I am.

JP Koning is a deep thinker about monetary policy and about the nature of money. He has been a full-scale supporter of my proposal to eliminate the zero lower bound since early on. Other than my coauthor Ruchir Agarwal for “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound,” I would trust JP to accurately represent my views on negative interest rate policy more than anyone else in the world. Anyone who wants to understand money or monetary poiicy should read Moneyness. I also especially enjoy JP’s Twitter presence.

David Beckworth: Macro and Other Market Musings

David Beckworth is one of the few other full-scale supporters of my proposals for negative interest rate policy in the blogosphere–as well as of Scott Sumner’s proposals. A nice example of this is “David Beckworth: “Miles and Scott’s Excellent Adventure” David Beckworth recently interviewed me at length in his Podcast series. I love his written introduction to that podcast. He writes:

Miles is a well-known advocate of breaching the zero lower bound via the adoption of negative interest rates. Moreover, he has shown how to do it without getting rid of physical cash. Miles sat down with me to discuss his ideas on this topic as well as how the macroeconomics profession has changed over the past few decades. I had a great time discussing these issues with Miles. You will enjoy the conversation too.

I would like to make several points on this controversial topic. First, if you believe in allowing markets to clear via the adjustment of prices, then you should in principle be supportive of negative interest rates. For an interest rate is just an intertemporal price–a price that clears resources across time–and sometimes a severe enough demand shock may require nominal rates to go negative for markets to clear. This is a point I have written about myself.

Second, central banks that have lowered interest rates to zero and in some cases below zero are not necessarily “artificially” depressing interest rates. It could be that a central bank is simply following the market-clearing level of interest rates–or the natural interest rate–down to lower levels as the economy weakens. This, in my view, is what most central banks have been doing in recent years. Too many observes miss this point.

David and I had an interesting discussion a while back that I made into the post “David Beckworth and Miles Kimball: The Padding on Top of the Zero Lower Bound.” This discussion has become somewhat dated as central banks look for less and less padding on top of the zero lower bound–many going to a negative amount of padding!

Simon Wren-Lewis: Mainly Macro

I have only interacted with Simon Wren-Lewis, but I have greatly admired many of his posts. He is much more Keynesian than I am (I am a Neomonetarist who looks to monetary policy for economic stabilization), but his posts are full of incisive insights. I would be very glad for more substantial interaction between our blogs.

Roger Farmer’s Economic Window

I have mainly connected with Roger Farmer over our mutual advocacy of sovereign wealth funds as a tool of macroeconomic policy. On that, see “Roger Farmer and Miles Kimball on the Value of Sovereign Wealth Funds for Economic Stabilization.” Roger’s views are interesting because they are so unique. You definitely won’t get the “same old thing” reading his blog. Roger and I interact quite a bit on Twitter.

Nick Rowe: Worthwhile Canadian Initiative

Though still writing in words with few equations, Nick’s posts lean toward the technical. In that vein, I like his post on monetary dominance, “Fewer Fiscal Multipliers and more Clarity from the Bank of Canada.” I use an argument from Nick’s post “Money is Always and Everywhere a Hot Potato” in “International Finance: A Primer.” Also, Nick gives his own relatively formal treatment of what I cover in “The Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate and the Short-Run Natural Interest Rate” and “On the Great Recession” in his post “Upward-sloping IS curves after Miles Kimball.”

Matthew Martin: Separating Hyperplanes

Matthew Martin was one of the earliest and best commenters on my blog. His blog is very innovative. I am delighted to see it gaining more recognition.

I really enjoyed meeting Bryan Caplan in person when I gave a seminar at George Mason University a little over a year ago. He is someone I could happily spend hours talking to. He is an extremely creative thinker, unafraid to go places that other people might disagree with if logic takes him there. He is a great fount of things you would be unlikely to think of on your own, but should be thinking about–with prompting from Bryan your only plausible path to considering them.

Paul Krugman: Conscience of a Liberal

Paul Krugman is someone who floats in the air like a demigod, mostly untouchable by a mere mortal like me. As far as I know, he has never once responded to my repeated accusation that he treats the zero lower bound as if it were a law of nature, rather than the policy choice that it is. He has occasionally linked to one of my posts or columns when it suited his purposes. Paul Krugman ignored my discussion of breaking through the zero lower bound and of the power of national lines of credit in “How Italy and the UK Can Stimulate Their Economies Without Further Damaging Their Credit Ratings” and referenced the post (in “Another Attack of the 90% Zombie”) only to criticize my reliance on Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff’s claims about the effects of debt on growth. On his chosen field of combat, Paul Krugman bested me, and I atoned for my mistake with “An Economist’s Mea Culpa: I Relied on Reinhart and Rogoff,” “After Crunching Reinhart and Rogoff’s Data, We Found No Evidence High Debt Slows Growth” and “Examining the Entrails: Is There Any Evidence for an Effect of Debt on Growth in the Reinhart and Rogoff Data?” More evidence that Paul Krugman knows of my work on eliminating the zero lower bound, but is unwilling to talk directly about it can be found in his post “Switzerland and the Inflation Hawks.” On other topics, Paul Krugman linked to my column with Noah Smith on Minnesota Macro and picked up on a serious error by a Wall Street Journal columnist from one of my posts and picked up on my criticism of John Taylor in “Contra John Taylor.” Leaving aside my frustrations over the parameters of Paul Krugman’s interactions with me, I find that he has a very interesting blog. I am almost always entertained, I quite often agree with him, and I find him a model of rhetorical skill even when I think he is wrong.

John Cochrane: The Grumpy Economist

Unlike Paul Krugman, John Cochrane is happy to interact with me. Indeed, I have had some extended email discussions with John that he has agreed we can publish as soon as I have a spot of time to organize them into blog posts as I have volunteered to do. Sometimes John and I are on the same side of a question, as you can see from “Anat Admati, Martin Hellwig and John Cochrane on Bank Capital Requirements.” Other times we disagree, as you can see from our debate about whether things other than paper currency are likely to create an effective lower bound on interest rates. On that, see:

I have Twitter friends who think that John Cochrane has become a right-wing hack. But what I notice is that John Cochrane is regularly drawn by the internal logic of economic arguments to points of view and policy positions that have nothing to with the standard right-wing line. John Cochrane is not predictable in what he writes, unlike many other bloggers and columnists; and he is very very smart. So he is well worth reading.

In saying what I said in the last paragraph, I realize I have a double standard: I hold center-right, center-left and left-wing bloggers and columnists to the standard of getting everything correct, while my standard for right-wing and heterodox left-wing bloggers and columnists is an easier one to meet: I look for interesting, useful ideas, even if the wheat is mixed in with off-the-mark chaff. This is less of a bilateral double standard viewing politics from an international perspective, where in rich countries generally, the US center-left is the international political center. (Personally, I am probably closer to the political center in the US than I am to the international political center.)

Update on Female Bloggers: Anna Earl asks a great question on Twitter about female bloggers. None of them were on the list I was working from, but the female bloggers I interact with most are Frances Coppola, Izabella Kaminska and Claudia Sahm. I recommend all of them highly. Twitter is a great way to keep track of their online activities. Here is my tweet with links to their Twitter feeds. Frances Coppola worries that banks will be hurt by negative interest rates, with deleterious effects on the economy. You can tap into that debate from our tweets to each other, with links. Izabella Kaminska is an advocate of electronic money. We share many common interests. Claudia Sahm is a very impressive former student and coauthor of mine who is one of the Fed’s top experts on consumption. Let me also recommend Bonnie Kavoussi, who wrote for the Huffington Post before coming to the University of Michigan as a student in our Masters of Applied Economics program. She has begun a career writing and editing economics books. I am hoping that Bonnie will help me write some books someday. Bonnie has a great Twitter feed. Here is a link to Bonnie’s blog.

… in which my grandfather, Spencer Woolley Kimball, is compared to Yoda.

Link to Wikipedia article on Walter Bagehot

Here is Peter Conti-Brown’s description of Walter Bagehot, from the Preface to his marvelous book The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve:

Finally, a word about the book’s epigraphs, all taken from the great Walter Bagehot. Bagehot—pronounced BADGE-it in American English, BADGE-ot in Britain, a shibboleth of sorts in central banking circles—is widely viewed as the intellectual godfather of modern central banking. Whether his world has much to say to ours is an open question, but there are few wordsmiths in financial history quite as able as he. He is the author of magnificent sentences, very interesting paragraphs, and sometimes frustratingly indeterminate books. But because of the power of those sentences, I borrow liberally from his iconic 1873 book, Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, for the epigraphs that introduce each chapter (except for chapter 4, which comes from his other famous book, The English Constitution). Bagehot obviously had nothing to say about the Federal Reserve System, which was founded decades after his death. And he barely had more to say about the U.S. financial system (he wasn’t very impressed with nineteenth-century U.S. finance). But his turns of phrases are too applicable and felicitous to pass by, even if the reader must change some of the proper nouns to make them relevant.

In his book “The Power and Independence of the Federal Reserve,” Peter Conti-Brown argues that Federal Reserve Bank Presidents are, in effect, important government officials, by virtue of voting on monetary policy, and so (a) should be chosen in a democratically accountable way and (b) to accord with the constitution, should be either appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the Senate, or treated as “inferior officers.”

I am like Justin Fox and many others at a 2015 Brookings event that Justin reports on in thinking that the Federal Reserve Bank Presidents voting on monetary policy in a way close to the way things are now is good for monetary policy. In particular, it helps in allowing a diversity of views to make its way into monetary policy. Crucially, each Federal Reserve Bank President has the staff to really investigate different angles on monetary policy. And indeed, one of the most valuable reforms would be to give more staff and more independence of the Governors in Washington DC from the Chair of the Fed–as well as higher salaries more in line with the Federal Reserve Bank Presidents so that they would be less tempted to quit as Governors after only a few years.

Despite thinking that the current de facto status of Federal Reserve Bank Presidents is good for monetary policy, and that indeed that the Governors’ status should be raised by giving them some of the attractive job characteristics that the Federal Reserve Bank Presidents have, I take the constitutional issue seriously. I wrote to Peter by email of an idea of how to make the Fed’s governance structure constitutional by clarifying that the Federal Reserve Bank Presidents’ are indeed inferior officers, de jure, and indeed making their appointment more consistent with being inferior officers, but otherwise keeping the role of Federal Reserve Bank Presidents essentially the same as now. Here is what I wrote, with a few words added for clarification:

I think it would be very interesting to investigate the extent to which–even without new legislation–a strong Chair, working with the Fed’s Chief Counsel, could implement the “Federal Reserve Bank Presidents as inferior officers” reform.

As far as removal goes, I think a legal report could take your line that constitutionally, as inferior officers, the bank presidents must be removable by the board–whether the statute said so or not–and that that was the legal position of the board would take to the extent the question of whether the presidents were inferior officers or whether a president was removable ever came up. This would presumably be associated with reassurances that the board had no intentions of removing any president any time soon. It would cause some kerfuffle, but that would die down reasonably soon after repeated assurances that the board had no intention of actually removing any president any time soon, but that it was just forced to the conclusion of its ability to do so by the law.

As far as appointment goes, the rules already give the board a substantial role in the appointment process. As I understand it, it already requires both the assent of the Board of Governors and the assent of the board of the particular federal reserve bank to make a president. The Board of Governors could easily be much more assertive in this process than it is. And indeed I think the trend is in that direction. For example, I heard that the FRB took a big role in the selection of the SF Fed Bank’s current president. Of course, the place to start would be for the Board of Governors to be extremely assertive in the choice of the president of the NY Fed.

I disagree with you about bank presidents voting on the FOMC. Because they have their own staffs and an attractive job that they will continue in for some time, they provide important diversity in viewpoints–both on the hawkish side and on the dovish side. I think greater Board of Governors assertiveness in the selection of bank presidents solves the most important institutional design problem from the standpoint of good policy outcomes, while simply asserting that the constitution overrides the statute so that the Board of Governors can remove bank presidents if it comes to that solves the constitutional problem.

Let me add this: if, to smart lawyers, this interpretation of the law seems right, one can imagine the chief lawyer of one of the regional Feds replying to a query from its president by saying:

I have good news and bad news.

The good news is that you are constitutional.

The bad news is that you can be fired.

“The cheapest fares are on days when fewer people are traveling … ‘In the end, the seats are going to fly.’”

The Chinese economy is not easy to understand. So I am always on the lookout for things that can help make it more understandable. This 12 and a half minute segment by Tyler Cowen is excellent.

I have one disagreement and one thing to add. The disagreement is that I don’t think “capital flight” has to be a big problem for the Chinese economy. The Chinese Yuan may need to depreciate; they have been using up reserves at a rapid clip to try to prop it up, which has to stop at some point, despite the large reserves they start with. But because China’s government and Chinese firms owe relatively little debt in any foreign currency, such a depreciation due to outward capital flows shouldn’t cause any huge problems. Indeed, it will help increase net exports, in line with the principles I discuss in my post “International Finance: A Primer.”

Nevertheless, the Chinese economy would be more balanced if Chinese households start doing more consumption spending. Many economists and foreign observers have recommended that China shore up its social safety net to reduce precautionary saving and thereby foster consumption. The additional point I wanted to make is that allowing higher interest rates on savings accounts might spur consumption in the Chinese case, where the marginal propensity to spend of the banks and their owners on the other side of that particular borrower/lender relationship might be lower than the households doing the saving–especially if the Chinese government tells those banks to keep doing a given quantity of lending, or if the rate at which Chinese banks lend is disconnected from the rate at which they pay interest to depositors. (In general, to see the effects of an interest rate change, try the kind of analysis I illustrate in “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates.” This Chinese case is unusual. For almost all borrower-lender relationships, a cut in interest rates is stimulative and an increase in rates is contractionary.)

“… there are few things we resist more staunchly, to the detriment of our own growth, than looking foolish for being wrong. The courageous … trip and fall, often in public, but get right back up and leap again.”

Experts say the struggle of two entrepreneurs highlights how the myriad rules governing driving schools — and 36 other highly regulated professions — stifle competition and inflate prices in France.

Having blogged through to the end of On Liberty, I know that what John Stuart Mill claims in the 9th paragraph of the “Introductory” to On Liberty is simple is anything but simple. He writes:

The object of this Essay is to assert one very simple principle, as entitled to govern absolutely the dealings of society with the individual in the way of compulsion and control, whether the means used be physical force in the form of legal penalties, or the moral coercion of public opinion. That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise. To justify that, the conduct from which it is desired to deter him, must be calculated to produce evil to some one else. The only part of the conduct of any one, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.

The first complexity is that the idea of “self-protection” or preventing harm to oneself as a necessity for setting down a social rule is not an adequate principle for preserving liberty. No doubt slaveholders felt they were harmed when Harriet Tubman helped slaves to escape on the Underground Railroad. That harm to their interests did not justify them in setting up rules requiring the return of runaway slaves. More generally, the principle of self-protection or preventing harm to oneself does not provide adequate guidance when someone’s actions harm one person and help another. In such cases, it matters how much one person is helped and how much another person is harmed.

The slavery case may seem easy, but consider this one. If one homeowner rents out a basement that might create more noise and somewhat exacerbated parking problems for the neighbors. On the other hand, it might greatly help the person who is now able to find a place to live because of this opportunity to be a renter. Is the community justified in prohibiting renting out basements because of the negative externality to the neighbors, or does the benefit to the person who now can find an affordable place to live in someone’s basement outweigh that negative externality?

On this first complexity, see for example “John Stuart Mill on Legitimate Ways to Hurt Other People.”

The second, related complexity is that the boundary between “self” and “other” for the purposes of establishing liberty is not always so easy to establish. Liberty is more than simply having one’s body untouched. At a minimum, some freedom of motion is needed for liberty; if one is confined to a prison, it is an affront to liberty no matter how well one’s body is taken care of. At another level, if one’s personal diary is confiscated every day and burned in the flames, that is an affront to liberty. Sometimes this kind of reasoning is taken to include all of the things an individual has produced as if they were a part of the person, with any affront to a person’s property being an affront to liberty.

But in some ways, an individual’s sensibility and feelings are a more central part of a person than that individual’s property. And yet, we dare not count an affront to someone’s sensibility as an affront to liberty in all cases since many people are quite offended by other people’s private behavior–for example, other people’s religious beliefs and worship practices or other people’s sexual expression. To treat an individual’s sensibility as an inviolable part of that person is to tread on other people’s liberty too much. So we dare not give an individual so wide a sphere of personal rights as to include too many sensibilities about other people’s actions.

The bottom line is that drawing lines between what is my personal sphere in which I have a broad freedom of action and what is your sphere in which you have a broad freedom of action is tricky. On this complexity, see for example my discussion in “John Stuart Mill on Being Offended at Other People’s Opinions or Private Conduct.” To me it seems that workable principles of liberty must draw boundaries for one’s own private interests–the extended “self”–that are (a) as nearly as possible the same size or extensiveness for each individual (equality in the size of extended self), (b) as large as possible, without (c) overlapping too severely. Thus, interestingly, equality comes in as part of the definition of liberty–not equality of result or even equality of opportunity, but equality of size of the extended self. That is, to the extent possible, there should be equality of the sphere of each individual’s interests that are recognized as that individual’s personal sphere in which shehe has great autonomy.

Also see Ben Zimmer’s Wall Street Journal article “‘They,’ the Singular Pronoun, Gets Popular.”