Quartz #24—>After Crunching Reinhart and Rogoff's Data, We Found No Evidence High Debt Slows Growth

Here is the full text of my 24th Quartz column, that I coauthored with Yichuan Wang, “After crunching Reinhart and Rogoff’s data, we’ve concluded that high debt does not slow growth.” It is now brought home to supplysideliberal.com (and soon to Yichuan's Synthenomics). It was first published on May 29, 2013. Links to all my other columns can be found here. In particular, don’t miss the follow-up column “Examining the Entrails: Is There Any Evidence for an Effect of Debt on Growth in the Reinhart and Rogoff Data?”

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© May 29, 2013: Miles Kimball and Yichuan Wang, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2014. All rights reserved.

(Yichuan has agreed to extend permission on the same terms that I do.)

This column had a strong response. I have included the text of my companion column, with links to many of the responses after the text of the column itself. (For the comments attached to that companion post, you will still have to go to the original posting.) Other followup posts can be found in my “Short-Run Fiscal Policy” sub-blog.

Leaving aside monetary policy, the textbook Keynesian remedy for recession is to increase government spending or cut taxes. The obvious problem with that is that higher government spending and lower taxes tend to put the government deeper in debt. So the announcement on April 15, 2013 by University of Massachusetts at Amherst economists Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin that Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff had made a mistake in their analysis claiming that debt leads to lower economic growth has been big news. Remarkably for a story so wonkish, the tale of Reinhart and Rogoff’s errors even made it onto the Colbert Report. Six weeks later, discussions of Herndon, Ash and Pollin’s challenge to Reinhart and Rogoff continue in earnest in the economics blogosphere, in the Wall Street Journal, and in the New York Times.

In defending the main conclusions of their work, while conceding some errors, Reinhart and Rogoff point out that even after the errors are corrected, there is a substantial negative correlation between debt levels and economic growth. That is a fair description of what Herndon, Ash and Pollin find, as discussed in an earlier Quartz column, “An Economist’s Mea Culpa: I relied on Reinhardt and Rogoff.” But, as mentioned there, and as Reinhart and Rogoff point out in their response to Herndon, Ash and Pollin, there is a key remaining issue of what causes what. It is well known among economists that low growth leads to extra debt because tax revenues go down and spending goes up in a recession. But does debt also cause low growth in a vicious cycle? That is the question.

We wanted to see for ourselves what Reinhart and Rogoff’s data could say about whether high national debt seems to cause low growth. In particular, we wanted to separate the effect of low growth in causing higher debt from any effect of higher debt in causing low growth. There is no way to do this perfectly. But we wanted to make the attempt. We had one key difference in our approach from many of the other analyses of Reinhart and Rogoff’s data: we decided to focus only on long-run effects. This is a way to avoid getting confused by the effects of business cycles such as the Great Recession that we are still recovering from. But one limitation of focusing on long-run effects is that it might leave out one of the more obvious problems with debt: the bond markets might at any time refuse to continue lending except at punitively high interest rates, causing debt crises like that have been faced by Greece, Ireland, and Cyprus, and to a lesser degree Spain and Italy. So far, debt crises like this have been rare for countries that have borrowed in their own currency, but are a serious danger for countries that borrow in a foreign currency or share a currency with many other countries in the euro zone.

Here is what we did to focus on long-run effects: to avoid being confused by business-cycle effects, we looked at the relationship between national debt and growth in the period of time from five to 10 years later. In their paper “Debt Overhangs, Past and Present,” Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, along with Vincent Reinhart, emphasize that most episodes of high national debt last a long time. That means that if high debt really causes low growth in a slow, corrosive way, we should be able to see high debt now associated with low growth far into the future for the simple reason that high debt now tends to be associated with high debt for quite some time into the future.

Here is the bottom line. Based on economic theory, it would be surprising indeed if high levels of national debt didn’t have at least some slow, corrosive negative effect on economic growth. And we still worry about the effects of debt. But the two of us could not find even a shred of evidence in the Reinhart and Rogoff data for a negative effect of government debt on growth.

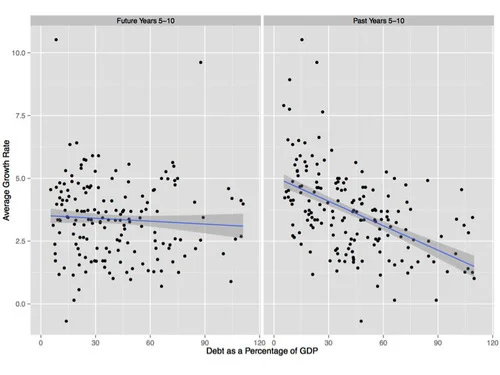

The graphs at the top show show our first take at analyzing the Reinhardt and Rogoff data. This first take seemed to indicate a large effect of low economic growth in the past in raising debt combined with a smaller, but still very important effect of high debt in lowering later economic growth. On the right panel of the graph above, you can see the strong downward slope that indicates a strong correlation between low growth rates in the period from ten years ago to five years ago with more debt, suggesting that low growth in the past causes high debt. On the left panel of the graph above, you can see the mild downward slope that indicates a weaker correlation between debt and lower growth in the period from five years later to ten years later, suggesting that debt might have some negative effect on growth in the long run. In order to avoid overstating the amount of data available, these graphs have only one dot for each five-year period in the data set. If our further analysis had confirmed these results, we were prepared to argue that the evidence suggested a serious worry about the effects of debt on growth. But the story the graphs above seem to tell dissolves on closer examination.

Given the strong effect past low growth seemed to have on debt, we felt that we needed to take into account the effect of past economic growth rates on debt more carefully when trying to tease out the effects in the other direction, of debt on later growth. Economists often use a technique called multiple regression analysis (or “ordinary least squares”) to take into account the effect of one thing when looking at the effect of something else. Here we are doing something that is quite close both in spirit and the numbers it generates for our analysis, but allows us to use graphs to show what is going on a little better.

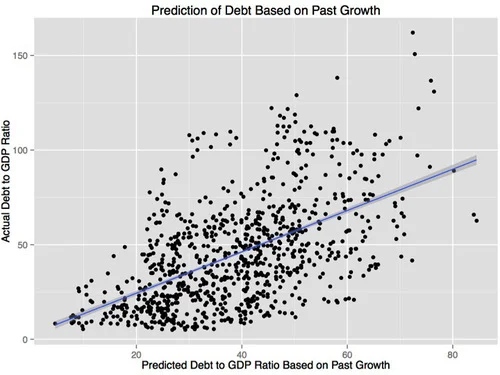

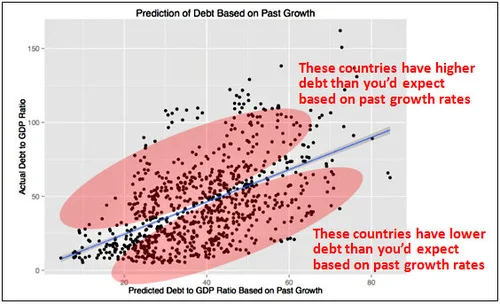

The effects of low economic growth in the past may not all come from business cycle effects. It is possible that there are political effects as well, in which a slowly growing pie to be divided makes it harder for different political factions to agree, resulting in deficits. Low growth in the past may also be a sign that a government is incompetent or dysfunctional in some other way that also causes high debt. So the way we took into account the effects of economic growth in the past on debt—and the effects on debt of the level of government competence that past growth may signify—was to look at what level of debt could be predicted by knowing the rates of economic growth from the past year, and in the three-year periods from 10 to 7 years ago, 7 to 4 years ago and 4 to 1 years ago. The graph below, labeled “Prediction of Debt Based on Past Growth” shows that knowing these various economic growth rates over the past 10 years helps a lot in predicting how high the ratio of national debt to GDP will be on a year by year basis. (Doing things on a year by year basis gives the best prediction, but means the graph has five times as many dots as the other scatter plots.) The “Prediction of Debt Based on Past Growth” graph shows that some countries, at some times, have debt above what one would expect based on past growth and some countries have debt below what one would expect based on past growth. If higher debt causes lower growth, then national debt beyond what could be predicted by past economic growth should be bad for future growth.

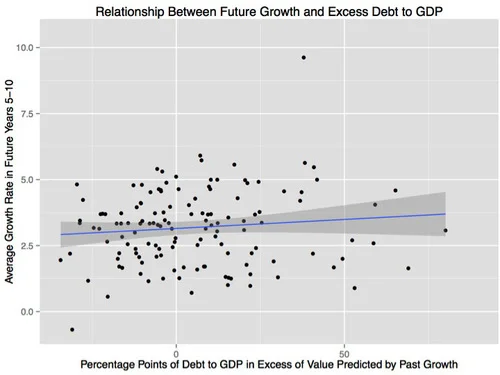

Our next graph below, labeled “Relationship Between Future Growth and Excess Debt to GDP” shows the relationship between a debt to GDP ratio beyond what would be predicted by past growth and economic growth 5 to 10 years later. Here there is no downward slope at all. In fact there is a small upward slope. This was surprising enough that we asked others we knew to see what they found when trying our basic approach. They bear no responsibility for our interpretation of the analysis here, but Owen Zidar, an economics graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, and Daniel Weagley, graduate student in finance at the University of Michigan were generous enough to analyze the data from our angle to help alert us if they found we were dramatically off course and to suggest various ways to handle details. (In addition, Yu She, a student in the master’s of applied economics program at the University of Michigan proofread our computer code.) We have no doubt that someone could use a slightly different data set or tweak the analysis enough to make the small upward slope into a small downward slope. But the fact that we got a small upward slope so easily (on our first try with this approach of controlling for past growth more carefully) means that there is no robust evidence in the Reinhart and Rogoff data set for a negative long-run effect of debt on future growth once the effects of past growth on debt are taken into account. (We still get an upward slope when we do things on a year-by-year basis instead of looking at non-overlapping five-year growth periods.)

Daniel Weagley raised a very interesting issue that the very slight upward slope shown for the “Relationship Between Future Growth and Excess Debt to GDP” is composed of two different kinds of evidence. Times when countries in the data set, on average, have higher debt than would be predicted tend to be associated with higher growth in the period from five to 10 years later. But at any time, countries that have debt that is unexpectedly high not only compared to their own past growth, but also compared to the unexpected debt of other countries at that time, do indeed tend to have lower growth five to 10 years later. It is only speculating, but this is what one might expect if the main mechanism for long-run effects of debt on growth is more of the short-run effect we mentioned above: the danger that the “bond market vigilantes” will start demanding high interest rates. It is hard for the bond market vigilantes to take their money out of all government bonds everywhere in the world, so having debt that looks high compared to other countries at any given time might be what matters most.

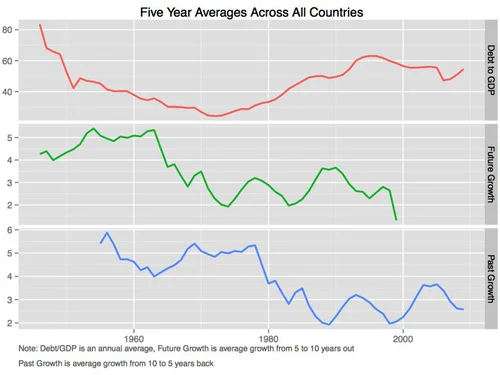

Our view is that evidence from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time are just as instructive as evidence from the cross-national evidence from debt in one country being higher than in other countries at a given time. Our last graph (just above) shows what the evidence from trends in average levels over time looks like. High debt levels in the late 1940s and the 1950s were followed five to 10 years later with relatively high growth. Low debt levels in the 1960s and 1970s were followed five to 10 years later by relatively low growth. High debt levels in the 1980s and 1990s were followed five to 10 years later by relatively high growth. If anyone can come up with a good argument for why this evidence from trends in the average levels over time should be dismissed, then only the cross-national evidence about debt in one country compared to another would remain, which by itself makes debt look bad for growth. But we argue that there is not enough justification to say that special occurrences each year make the evidence from trends in the average levels over time worthless. (Technically, we don’t think it is appropriate to use “year fixed effects” to soak up and throw away evidence from those trends over time in the average level of debt around the world.)

We don’t want anyone to take away the message that high levels of national debt are a matter of no concern. As discussed in “Why Austerity Budgets Won’t Save Your Economy,” the big problem with debt is that the only ways to avoid paying it back or paying interest on it forever are national bankruptcy or hyper-inflation. And unless the borrowed money is spent in ways that foster economic growth in a big way, paying it back or paying interest on it forever will mean future pain in the form of higher taxes or lower spending.

There is very little evidence that spending borrowed money on conventional Keynesian stimulus—spent in the ways dictated by what has become normal politics in the US, Europe and Japan—(or the kinds of tax cuts typically proposed) can stimulate the economy enough to avoid having to raise taxes or cut spending in the future to pay the debt back. There are three main ways to use debt to increase growth enough to avoid having to raise taxes or cut spending later:

1. Spending on national investments that have a very high return, such as in scientific research, fixing roads or bridges that have been sorely neglected.

2. Using government support to catalyze private borrowing by firms and households, such as government support for student loans, and temporary investment tax credits or Federal Lines of Credit to households used as a stimulus measure.

3. Issuing debt to create a sovereign wealth fund—that is, putting the money into the corporate stock and bond markets instead of spending it, as discussed in “Why the US needs its own sovereign wealth fund.” For anyone who thinks government debt is important as a form of collateral for private firms (see “How a US Sovereign Wealth Fund Can Alleviate a Scarcity of Safe Assets”), this is the way to get those benefits of debt, while earning more interest and dividends for tax payers than the extra debt costs. And a sovereign wealth fund (like breaking through the zero lower bound with electronic money) makes the tilt of governments toward short-term financing caused by current quantitative easing policies unnecessary.

But even if debt is used in ways that do require higher taxes or lower spending in the future, it may sometimes be worth it. If a country has its own currency, and borrows using appropriate long-term debt (so it only has to refinance a small fraction of the debt each year) the danger from bond market vigilantes can be kept to a minimum. And other than the danger from bond market vigilantes, we find no persuasive evidence from Reinhart and Rogoff’s data set to worry about anything but the higher future taxes or lower future spending needed to pay for that long-term debt. We look forward to further evidence and further thinking on the effects of debt. But our bottom line from this analysis, and the thinking we have been able to articulate above, is this: Done carefully, debt is not damning. Debt is just debt.

Companion Post

The title chosen by our editor is too strong, but not so much so that I objected to it; the title of this post is more accurate.

Yichuan only recently finished his first year at the University of Michigan. Yichuan’s blog is Synthenomics. You can see Yichuan on Twitter here. Let me say already that from reading Yichuan’s blog and working with him on this column, I know enough to strongly recommend Yichuan for admission to any Ph.D. program in economics in the world. He should finish has bachelor’s degree first, though.

I genuinely went into our analysis expecting to find evidence that high debt does cause low growth, though of course, to a much smaller extent than low growth causes high debt. I was fully prepared to argue (first to Yichuan and then to the world) that even a statistically insignificant negative effect of debt on growth that was plausibly causal had to be taken seriously from a Bayesian perspective. Our analysis set out the minimal hurdles I felt had to be jumped over to convince me that there was some solid evidence that high debt causes low growth. A key jump was not completed. That shifted my views.

I hope others will try to replicate our findings. That should let me rest easier.

From a theoretical point of view, I am especially intrigued by the possibility that any effect on growth from refinancing difficulties might depend on a country’s debt to GDP ratio compared to that of other countries. What I find remarkable is that despite the likely negative effect of debt on growth from refinancing difficulties, we found no overall negative effect of debt on growth. It is as if there is some other, positive effect of debt on growth to the extent a country’s relative debt position stays the same. Besides the obvious, but uncommonly realized, possibility of very wisely deployed deficit spending, I can think of two intriguing mechanisms that could generate such an effect. First, from a supply-side point of view, lower tax rates now could make growth look higher now, perhaps at the expense of growth at some future date when taxes have to be raised to pay off the debt, with interest. Second, government debt increases the supply of liquid (and often relatively safe) assets in the economy that can serve as good collateral. Any such effect could be achieved without creating a need for higher future taxes or lower future spending by investing the money raised in corporate stocks and bonds through a sovereign wealth fund.

I have thought a little about why borrowing in a currency one can print unilaterally makes such a difference to the reactions of the bond market to debt. One might think that the danger of repudiating the implied real debt repayment promises by inflation would mean the risks to bondholders for debt in one’s own currency would be almost the same as for debt in a foreign currency or a shared currency like the euro. But it is one thing to fear actual disappointing real repayment spread over some time and another thing to have to fear that the fear of other bondholders will cause a sudden inability of a government to make the next payment at all.

Note: Brad Delong writes:

Miles Kimball and Yichuan Wang confirm Arin Dube: Guest Post: Reinhart/Rogoff and Growth in a Time Before Debt | Next New Deal:

As I tweeted,

.@delong undersells our results. I would have read Arin Dube’s results alone as saying high debt *does* slow growth.

*Of course* low growth causes debt in a big way. But we need to know if high debt causes low growth, too. No ev it does!

In tweeting this, I mean,if I were convinced Arin Dube’s left graph were causal, the left graph seems to suggest that higher debt causes low growth in a very important way, though of course not in as big a way as slow growth causes higher debt. If it were causal, the left graph suggests it is the first 30% on the debt to GDP ratio that has the biggest effect on growth, not any 90% threshold. Yichuan and I are saying that the seeming effect of the first 30% on the debt to GDP ratio could be due in important measure to the effect of growth on debt, plus some serial correlation in growth rates. The nonlinearity could come from the fact that it takes quite high growth rates to keep a country from have some significant amounts of debt—as indicated by Arin Dube’s right graph, which is more likely to be primarily causal.

By the way, I should say that Yichuan and I had seen the Rortybomb piece on Arin Dube’s analysis, but we were not satisfied with it. But I want to give credit for this as a starting place for Yichuan and me in our thinking.

Brad Delong’s Reply: Thanks to Brad DeLong for posting the note above as part of his post “DeLong Smackdown Watch: Miles Kimball Says That Kimball and Wang is Much Stronger than Dube.”

Brad replies:

From my perspective, I tend to say that of course high debt causes low growth—if high debt makes people fearful, and leads to low equity valuations and high interest rates. The question is: what happens in the case of high debt when it comes accompanied by low interest rates and high equity values, whether on its own or via financial repression?

Thus I find Kimball and Wang’s results a little too strong on the high-debt-doesn’t-matter side for me to be entirely comfortable…

My Thoughts about What Brad Says in the Quote Just Above: As I noted above, my reaction is to what we Yichuan and I found is similar to Brad’s. There must be a negative effective of debt on growth through the bond vigilante channel, as Yichuan and I emphasize in our interpretation. For example, in our final paragraph, Yichuan and I write:

…other than the danger from bond market vigilantes, we find no persuasive evidence from Reinhart and Rogoff’s data set to worry about anything but the higher future taxes or lower future spending needed to pay for that long-term debt.

The surprise is the pattern that when countries around the world shifted toward higher debt than would be predicted by past growth, that later growth turned out to be somewhat higher than after countries around the world shifted to lower debt. It may be possible to explain why that evidence from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time should be dismissed, but if not, we should try to understand those time series patterns. It is hard to get definitive answers from the relatively small amount of evidence in macroeconomic time series, or even macroeconomic panels across countries, but given the importance of the issues, I think it is worth pondering the meaning of what limited evidence there is from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time. That is particularly true since in the current crisis, many people have, recommended precisely the kind of worldwide increase deficit spending—and therefore debt levels—that this limited evidence speaks to.

I am perfectly comfortable with the idea that the evidence from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time is limited enough so theoretical reasoning that shifts our priors could overwhelm the signal from the data. But I want to see that theoretical reasoning. And I would like to get reactions to my theoretical speculations above, about (1) supply-side benefits of lower taxes that reverse in sign in the future when the debt is paid for and (2) liquidity effects of government debt (which may also have a price later because of financial cycle dynamics).

Matt Yglesias’s Reaction: On MoneyBox, you can see Matthew Yglesias’s piece “After Running the Numbers Carefully There’s No Evidence that High Debt Levels Cause Slow Growth.” As I tweeted:

Don’t miss this excellent piece by @mattyglesias about my column with @yichuanw on debt and growth. Matt gets it.

In the preamble of my post bringing the full text of “An Economist’s Mea Culpa: I Relied on Reihnart and Rogoff" home to supplysideliberal.com, I write:

In terms of what Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff should have done that they didn’t do, “Be very careful to double-check for mistakes” is obvious. But on consideration, I also felt dismayed that they didn’t do a bit more analysis on their data early on to make a rudimentary attempt to answer the question of causality. I wouldn’t have said it quite as strongly as Matthew Yglesias, but the sentiment is basically the same.

Paul Krugman’s Reaction: On his blog, Paul Krugman characterized our findings this way:

There is pretty good evidence that the relationship is not, in fact, causal, that low growth mainly causes high debt rather than the other way around.

Kevin Drum’s Reaction: On the Mother Jones blog, Kevin Drum gives a good take on our findings in his post “Debt Doesn’t Cause Low Growth. Low Growth Causes Low Growth.” He notices that we are not fans of debt. I like his version of one of our graphs:

Mark Gongloff’s Reaction: On Huffington Post, Mark Gongloff’s“Reinhart and Rogoff’s Pro-Austerity Research Now Even More Thoroughly Debunked by Studies” writes:

…University of Michigan economics professor Miles Kimball and University of Michigan undergraduate student Yichuan Wang write that they have crunched Reinhart and Rogoff’s data and found “not even a shred of evidence" that high debt levels lead to slower economic growth.

And a new paper by University of Massachusetts professor Arindrajit Dube finds evidence that Reinhart and Rogoff had the relationship between growth and debt backwards: Slow growth appears to cause higher debt, if anything….

This contradicts the conclusion of Reinhart and Rogoff’s 2010 paper, “Growth in a Time of Debt,” which has been used to justify austerity programs around the world. In that paper, and in many other papers, op-ed pieces and congressional testimony over the years, Reinhart And Rogoff have warned that high debt slows down growth, making it a huge problem to be dealt with immediately. The human costs of this error have been enormous….

At the same time, they have tried to distance themselves a bit from the chicken-and-egg problem of whether debt causes slow growth, or vice-versa. "The frontier question for research is the issue of causality,“ [Reinhart and Rogoff] said in their lengthy New York Times piece responding to Herndon. It looks like they should have thought a little harder about that frontier question three years ago.

There is an accompanying video by Zach Carter.

Paul Andrews Raises the Issue of Selection Bias: The most important response to our column that I have seen so far is Paul Andrews’s post "None the Wiser After Reinhart, Rogoff, et al.” This is the kind of response we were hoping for when we wrote “We look forward to further evidence and further thinking on the effects of debt.” Paul trenchantly points out the potential importance of selection bias:

What has not been highlighted though is that the Reinhart and Rogoff correlation as it stands now is potentially massively understated. Why? Due to selection bias, and the lack of a proper treatment of the nastiest effects of high debt: debt defaults and currency crises.

The Reinhart and Rogoff correlation is potentially artificially low due to selection bias. The core of their study focuses on 20 or so of the most healthy economies the world has ever seen. A random sampling of all economies would produce a more realistic correlation. Even this would entail a significant selection bias as there is likely to be a high correlation between countries who default on their debt and countries who fail to keep proper statistics.

Furthermore Reinhart and Rogoff’s study does not contain adjustments for debt defaults or currency crises. Any examples of debt defaults just show in the data as reductions in debt. So, if a country ran up massive debt, could’t pay it back, and defaulted, no problem! Debt goes to a lower figure, the ruinous effects of the run-up in debt is ignored. Any low growth ensuing from the default doesn’t look like it was caused by debt, because the debt no longer exists!

I think this issue needs to be taken very seriously. It would be a great public service for someone to put together the needed data set.

Note that Paul Andrews views are in line with our interpretation of our findings. Let me repeat our interpretation, with added emphasis:

…other than the danger from bond market vigilantes, we find no persuasive evidence from Reinhart and Rogoff’s data set to worry about anything but the higher future taxes or lower future spending needed to pay for that long-term debt.

Of course, it is disruptive to have a national bankruptcy. And national bankruptcies are more likely to happen at high levels of debt than low levels of debt (though other things matter as well, such as the efficiency of a nation’s tax system). And the fear by bondholders of a national bankruptcy can raise interest rates on government bonds in a way that can be very costly for a country. The key question for which the existing Reinhart and Rogoff data set is reasonably appropriate is the question of whether an advanced country has anything to fear from debt even if, for that particular country, no one ever seriously doubts that country will continue to pay on its debts.