Yichuan Wang: Did Dish Distort the Auction?

Links to Yichuan’s LinkedIn Page, his Medium page and to his blog Synthenomics.

Yichuan Wang is my coauthor on two very popular Quartz columns, “After Crunching Reinhart and Rogoff’s Data, We Found No Evidence High Debt Slows Growth” and “Examining the Entrails: Is There Any Evidence for an Effect of Debt on Growth in the Reinhart and Rogoff Data?” along with other posts about Reinhart and Rogoff’s data linked there. Along with Fumio Hayashi and Yoshiro Tsutsui, he is also my coauthor on a (not yet completed) academic paper on the dynamics of happiness. And he is a Quartz columnist in his own right. As an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, he is taking my “Monetary and Financial Theory” class this semester, and has been writing three blog posts a week in that capacity. Yichuan has his own blog, Synthenomics, but I asked him if I could publish this very interesting and sophisticated post as a guest post–the 8th student guest post this semester. Here is Yichuan:

Critics of Dish’s bidding strategies during the most recent AWS auction need to distinguish the difference between distorting prices and distorting taxpayer intent. While exploiting “small-business” tax breaks is distasteful because it violates the original intent of promoting business by minorities, such a payment subsidy likely increased the revenues from an auction which would have otherwise been dominated by AT&T and Verizon.

First, some background. The Advanced Wireless Services — 3 auction was an FCC auction for wireless spectrum. “Spectrum works like lanes on a highway, and wireless carriers have to buy more of it as they add subscribers and traffic increases.” As such, obtaining spectrum during these auctions is critical for companies who may wish to expand their wireless offerings.

AT&T and Verizon are obvious examples of such companies. But the real surprise was that Dish, a satellite TV company, won $13.3 bn. in spectrum in the auctions. Dish’s strategy relied on coordinating with three other “small business” entities. This had two benefits. First, it allowed a more complex bidding strategy. Because bids were anonymous, this created an illusion of more competition and drove prices higher. Second, it allowed Dish to benefit from a small business subsidy that took $3.3 billion dollars off of the sticker price.

I sympathize with comments from FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai that Dish’s bidding strategy “makes a mockery” of the “small business” part of the tax break. But is this a “distortion”?

In standard auction theory, we are typically concerned about two measures of efficiency. First, is the auction allocatively efficient? Second, does the auction maximize revenue? The first criterion is concerned with whether the spectrum is allocated to the firms who most value the spectrum. The second is concerned with whether the government is extorting — err, raising — the maximum amount of revenue from the bidders.

These two goals are often at odds. For example, suppose you have an auction system that is allocatively efficient, but the firm who values the spectrum the highest has much more wealth than all the other bidders. Think of this firm as AT&T. If AT&T is aware of this, then their optimal bid is much less than their true valuation of the spectrum — why pay more when they don’t have to? This, of course, screws over the FCC. So one possibility is to put in a minimum bid. But if you put this minimum bid too high, then nobody will bid and you lose allocative efficiency. But so long as you’re reasonable, you can raise much more revenue this way.

So did Dish make the auctions less allocatively efficient? On face, the answer seems to be yes. If Dish had a special price advantage due to tax benefits that could have unfairly given it spectrum that it didn’t deserve, then that could mean the spectrum wasn’t given to those who value it most.

But this doesn’t hold if Dish plans on monetizing its spectrum by selling it to other firms. T-Mobile has criticized Dish for hoarding spectrum and treating it more like a trade-able financial security. But if Dish sells its spectrum to another firm, then in the end the spectrum still ends up with a firm that values it most. Admittedly, Dish is engaging in tax-arbitrage — buying spectrum at tax advantaged prices and turning around to sell it to other less subsidy endowed firms. But this is a criticism of how Dish flaunts taxpayer intent, not of how Dish reduces allocative efficiency.

While the effect on efficiency is a wash, it’s clear that giving Dish a tax + strategic benefit in the bidding process dramatically raised revenues for the government. One estimate is that Dish’s actions raised the value of the auction by $20 bn. AT&T and Verizon could not just put in bids that were “big enough” — Dish and its subsidiaries made sure that AT&T and Verizon paid their valuations. In this light, Dish’s tax break could instead be seen as a tool to prevent Verizon and AT&T from dominating the auction.

Given this, it’s natural that AT&T and T-Mobile are crying foul. But in an auction with asymmetric bidders, tax subsidies that seem “unfair” may still be efficient and even revenue increasing.

Chris Rockwell: Has a Master’s Degree Become a Negative Job Market Signal?

Chris Rockwell’s LinkedIn Homepage

I wrote positively about Master’s degrees in economics in “On Master’s Programs in Economics.” In the 7th student guest post this semester, Chris Rockwell effectively expresses skepticism about the value of most master’s degrees. There is some resonance with what I say in my column “The Coming Transformation of Education: Degrees Won’t Matter Anymore, Skills Will.” Here is Chris:

Why a masters degree can make candidates less desirable to employers

Traditionally further education was associated with higher intelligence, increased income and higher social status. However, these correlations have changed drastically and now many of the most talented, qualified undergrads actually do not immediately enter graduate school. Because of this, I believe having a masters degree can actually make candidates appear less valuable to employers.

To estimate the average talent of those who get a masters degree, I will consider the option of obtaining this degree from a few different perspectives. As stated earlier, I believe some groups may choose not to get one, even if they could. This is due to graduate school being very expensive and requiring key time out of the work force. Additionally, getting a masters degree can be risky given upon graduation given there is no guarantee of a high quality job. I think masters candidates break nicely into three pools; all of them having different costs and benefits. Note I will examine the effect of a masters degree from a purely financial perspective, but I assert this is reasonable given people who are less interested in money would be more likely to get a PHD anyway.

First, I will consider an undergrad from the US with some competence, relatively good grades and solid test scores (for example, Michigan grad from random major with 3.5, little work experience, and a 80th percentile GRE). I assume this student might get some job offers, but they will probably not be stellar and might be closer to the $40-50k / year range. This student is basically faced with two options: school or work. Suppose if this student were to attain a masters degree it would be in business — the best performing grad school financially. In this case, after 2 years of missing work and $200k more debt, they would probably be looking at a salary closer to $80,000. All in all, Forbes calculated this is better than the alternative for this student. (A 10 year back-of-the-envelope calculation supports this: $80k * 10 – $200k = $600k > $50k * 10 = $500k).

The next group of students are international and talented — good enough to get into a comparable graduate university. However, these candidates often do not have the opportunity to pursue a job out of undergrad because of work visa restrictions or lack of English fluency. Hence, for them graduate school can be a must.

The final group of students I am considering are those who are excellent undergraduates and have the ability to land top offers. These offers can pay very well, often including base salaries ranging from $60,000 – $120,000. For students with such strong job offers, attending graduate school will generally not raise wage in any meaningful way in the near future. For example, at many top firms employees fresh out of graduate school with no work experience are paid the same wage or only a slightly higher wage than their undergraduate peers. Hence, for these top undergraduates, attending grad school right away makes no sense: doing so could in fact put them in a worse job market than the one they face upon graduation (not to mention cost and lost time).

So, under the assumption students maximize income, undergrads who attend grad school are often less talented than those who go straight into the work force. It follows that for recruiters at top firms, who only consider these three pools of people anyway (nobody with below a 3.5 for example), candidates who have received a graduate degree actually appear less attractive than those who have not. The clear exception to this is jobs requiring a masters degree, however many employers hiring for technical roles will teach undergrads on the job anyway.

Considering having a masters degree could be a negative job market signal, it might be surprising to note grad school attendance continues to climb. However, this actually makes sense because for most employees having a masters degree is still probably a positive signal. The group of less talented undergrads who get a masters are in general more desirable than their peers who do not. Hence it seems reasonable to conclude students with masters degrees are likely to be somewhat talented but probably not the best hires possible for employers.

In conclusion, modern graduate schools attract talented workers, but often not the best. The opportunity and monetary cost associated make these schools obsolete for the most talented individuals. In 2015, top firms should focus on undergrads when recruiting.

Noah Smith—Jews: The Parting of the Ways

This is Noah’s 11th guest religion post on supplysideliberal.com. Don’t miss Noah’s other guest religion posts!

Here is Noah:

What is Judaism? Is it a religion, an ethnicity, a culture, or a nation? It’s been all of these things, but what it really is, is a fellowship - a group of people who feel a connection to each other across time and space. More has probably been written about Jews, relative to their population size, than about any other fellowship of people on Earth. Many people can rattle off a list of Jewish accomplishments, either individual (polio vaccine, relativity, Facebook), or collective (ethical monotheism, Hollywood).

But the fellowship is coming to an end. Judaism is breaking up into (at least) four groups, which increasingly feel no common bond with each other.

The first group are the Israelis. Actually, this group is far from homogeneous, since that nation is divided between secular/leftist and Orthodox religious groups, as well as national ancestries. But in general, Israelis have a culture that noticeably sets them apart from Jews elsewhere. Universal military service, constant conflict with surrounding peoples, and the experience of nation-building has forged a new culture in Israel that seems foreign to many Jews in America and elsewhere.

The second group are the secular American Jews (yours truly included). We’re mostly liberal, educated, and secular. Culturally, we’re not very much different at all from lapsed Catholics, Unitarians, weekend Buddhists, or atheists. We mostly marry non-Jews. Most of us grew up without experiencing anti-Semitism. We are very assimilated into the general culture of the United States, and soon we will cease to exist as a distinct group at all.

The third group are the Ultra-Orthodox or Hasidic Jews, who have reacted to the modern world by retreating into ever more drastic medievalism. Hasidic communities are, to modern sensibilities, a parade of horrors. Sex abuse is rampant. Racism is endemic. Women are second-class citizens. There are herpes outbreaks from rabbis sucking the blood off of circumcision wounds. I wish I were exaggerating, but I’m not.

The fourth group are European Jews. Having survived the Holocaust, they live mostly as their ancestors did–as a distinct, mostly isolated religious minority, facing a slow steady assault of anti-Semitism.

These four groups are diverging from each other culturally, religiously, politically, and ethically. American Jews are slowly losing their emotional connection to Israel, and diverge sharply from Israelis on issues like Iran and Palestine. (On this, don’t miss Daniel Gordis’s Bloomberg View piece “American Jews Finding It Harder to Like Israel.”) As for the Hasids, their values are about as alien to other American Jews as those of ISIS - even my grandmother, a fluent Yiddish speaker and someone with a very strong Jewish identity, reviled the Hasidic culture and often told stories about its barbarism. As for European Jews, no one even hears very much about them anymore - the Holocaust severed a lot of family ties, and language barriers are hard to overcome.

So we have come to a parting of the ways. The fellowship of the Jews is broken, never to be reforged.

Actually, this shift was probably underway well before the modern age. The Industrial Revolution and the era of nationalism opened up sleepy Jewish communities throughout Europe. Jews began to assimilate into mainstream life in places like France, Germany, and the UK. Conflicts began between Zionists and anti-Zionists, religious and secular. The breakup of Judaism was interrupted by the Holocaust, which united Jews in suffering. But that interruption was temporary - eventually, the forces of globalization, secularization, and nationalism were destined to put an end to the strange little European subculture of yesteryear.

Is the end of the Jewish fellowship something to lament? I don’t think so. Cultures are adaptations to the demands of the age, and the age we live in now is just a very different one than the age that created the old European Jewish culture. As a character once said in Cory Doctorow’s Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom, “It’s not a museum, it’s a ride.” There are plenty of new identities and fellowships to be formed in the modern world. I would feel much more in common with the average science fiction fan, or Flaming Lips fan, or Stanford graduate than I would with the average Jewish person in France. If I have dual loyalties, they lie with Japan, not Israel.

Anyway, there will always be Jews out there - someone to wear the silly hats, to keep all the old rules. The Hasidic have very high birth rates. But as for the rest of us, we’re on to the next thing.

My Former Quartz Editor, Mitra Kalita Becomes Managing Editor for Editorial Strategy at the Los Angeles Times →

Mitra Kalita is the one who noticed my blog very early on back in Summer 2012 and recruited me to write for Quartz. (In particular, she noticed my post “Why My Retirement Savings Accounts are Currently 100% in the Stock Market,” which appeared on August 1, 2012.) Having not only worked with her as an editor, but having had several fascinating phone conversations about the strategy for Quartz and other online publications, I am not surprised that the Los Angeles Times has recruited her as Managing Editor for Editorial Strategy. The article linked above gives more details.

My best wishes and congratulations!

JP Koning and Miles Kimball Discuss Negative Interest Rate Alternatives

I had a very interesting email discussion with JP Koning about negative interest rate alternatives. I appreciate his having given permission to make this public.

JP Koning: Let’s say central banks adopt your crawling peg idea and drop rates to -5%. However, retailers continue to set almost all prices in terms of paper dollar rather than switching to the electronic dollar. Why is this a bad thing? Why does the success of a crawling peg hinge on retailers make the switch to the electronic dollar as unit of account?

One way I have been trying to puzzle this out is by thinking about Marvin Goodfriend’s idea of a suspension of payment in paper, which you refer to in your paper ‘Breaking though the zero lower bound’. Under Goodfriend’s scheme, if retailers continue to set prices in terms of paper currency rather than electronic dollars, each ratcheting down in interest rates below 0% by a central bank will cause a one- time jump in the value of paper dollars, or deflation, which would be a dangerous thing. If retailers had already been encouraged to switch the unit of account to electronic dollars, the problem would be fixed. However, I’m not sure if this particular justification for the necessity of retail adoption of electronic dollars as the unit of account transfers over to your crawling peg scheme.

So why is it so necessary that retailers make the unit of account switch?

Miles Kimball: This is a deep question that I have not yet fully plumbed, but here are the considerations that make me go around saying that the electronic unit of account is important.

1. If inflation is sticky in relation to a paper unit of account, then there is still an effective zero lower bound, since the paper currency earns a zero interest rate in the unit of account, which with (let’s say) low sticky inflation leads to a high real interest rate.

2. (This is a post I have been planning to write for a long time:) The changing exchange rate with electronic money does lead to a large increase in the money supply relative to the paper dollar numeraire that will credibly not be reversed, since ultimately the central bank expects people to switch to the electronic dollar numeraire. Suppose that does create inflation relative to the electronic dollar numeraire. Until people do switch to the new electronic dollar numeraire, that inflation relative to the paper dollar numeraire causes the usual costs: distortions of relative prices, menu cost expenditure, confusions, variance.

Thus, it is much better if people can be encouraged to use the electronic dollar numeraire. As I say in my presentations, I think the government can make that happen. After all, for all we know, we are already on an electronic dollar standard. It is hard to know what the private markets would do without a nudge if the paper dollar goes off par. With nudges such as tax accounting in electronic dollars, other accounting standards in electronic dollars–and if needed–a requirement that firms (whether they have a paper price or not) affirmatively post prices in electronic dollars, I have every confidence that the electronic dollar can be made the unit of account.

Of course, it helps if a large fraction of transactions is done in electronic dollar terms before the transition.

JP: Miles, when you get the chance can you critique my recent post? I’m trying to work out some “lite” techniques for breaking below the the zero lower bound. I believe they would work, but the devil’s in the details.

A lazy central banker’s guide to escaping liquidity traps.

Miles: Ken Rogoff suggests getting rid of the highest denomination notes first as the path toward eliminating paper currency entirely.

Ruchir Agarwal (my coauthor on the nascent academic paper on eliminating the zero lower bound) and I think that eliminating high denomination notes is a nice way to lower the fraction of transactions in paper currency in order to ease the transition into a crawling peg.

I think even the hardest-core version of eliminating high denomination notes (say $100s and above, then $50s–ordinary people mostly use $20s and below) of saying people have to turn them in is not all that radical. But if something less radical is needed, I like the idea of just not printing more.

One important thing in favor of the “not printing more” option that you might mention is that it just might be within the legal authority of the Fed + Executive branch (without new legislation) even if the crawling peg is not. But I need Greg Shill’s upcoming series of guest posts before I know things like that.

I had some responses to your paragraph here:

7) There are a few drawbacks to a crawling peg. Driving a wedge between paper and electronic currency creates two different sets of prices at the till, one for deposits and the other for cash. A chocolate bar, for instance, might have a sticker price of $1.00 in electronic money, but require a cash payment of $1.05. This will be confusing and inconvenient for shoppers, necessitating an expensive and costly education campaign by our central banker. According to Kimball, instituting a crawling peg requires that a nation enact a unit of account switch. Prices must be set in terms of electronic currency, not paper currency, otherwise the central bank will lose control over the price level. While a switch in standards is by no means impossible, it does require time and effort.

1. First of all, we may well be on an e-dollar standard already. It is not easy to tell when paper dollars are at par. So I don’t count this as necessarily a switch in the unit of account. Rather it is resolving an ambiguity in what the unit of account will be in favor of the e-dollar. That, I think is much easier than a switch in the unit of account.

2. I routinely argue (as you can see in my Powerpoint file and in my interview with Alexander Trentin

SNB should introduce a fee on paper currency

that up to something like a 4% paper currency deposit fee (which could easily be all that is ever needed, since -4% rates for 1 year are powerful enough to get a robust recovery in many countries), paper currency would probably be accepted at par at most retailers that deal in cash, since those retailers are now only getting about 96 cents on the dollar when people pay with American Express cards. Paper that yielded 96 cents on the dollar would look just as good.

But also, it really isn’t that big a deal if, say, paper is running at a 7% discount so that retailers no longer accept it at par at the cash register. That is no more complicated than a 7% sales tax at the cash register, which people don’t blink an eye at.

Notice that the front end of the crawling peg (a discount of, say, 0 to 4 or 5%) is most important for initial acceptance of the program. In the region where lite programs could go, the crawling peg is also very light, since cash would almost surely be at par at retailers. So I would argue that where a lite program will work, the crawling peg is also easy, and because it has the potential to go further, will have the advantage of creating stimulative expectations to a much greater degree than an approach that is limited to the lite region.

Miles: On further thought, although it is great for crime-fighting, making everyone turn in their $100 and $50 bills by a given date may be seen as somewhat draconian. Saying that after a certain date the Fed will accept them only at a discount, that will gradually increase, then pick up speed is a nice way to both (a) do the elimination of high-denomination bills in a less draconian way and (b) get people used to the idea of exchange rates for paper currency.

JP: Miles, here’s the first bit of my response, the rest later this week!

1. First of all, we may well be on an e-dollar standard already. It is not easy to tell when paper dollars are at par. So I don’t count this as necessarily a switch in the unit of account. Rather it is resolving an ambiguity in what the unit of account will be in favor of the e-dollar. That, I think is much easier than a switch in the unit of account.

While I agree that e-dollars are important, I think that we are probably on some sort of odd mixed e-standard/cash standard. I see it as being very similar to bimetallism; one unit, two different definitions that vary be retailer. I’ve written before about a Visa/MasterCard standard (see these two posts [1][2]).

Things get even more complicated if we factor in debit transactions: they are more expensive than cash from the perspective of a retailer, but less expensive than credit card transactions, and may provide a third potential definition for the unit of account.

It will be interesting to see if new rules allowing US retailers to put surcharges on credit card payments will result in a shift back to using paper dollars as the unit of account.

Merchant Surcharging – Understanding Payment Card Changes

One of the reasons I touched on the unit of account switch in my post is because of Scott Sumner. He recently wrote:

Nonetheless, it is probably impossible to pay negative interest rate on currency. Nor do I think it is feasible to make it so that currency is no longer a medium of account (as Miles Kimball proposed.)

Central banking in a negative seignorage world

I don’t know how common Sumner’s criticism is, but for those like him who don’t think that removing currency as the “medium of account” is feasible, then lite alternatives may be an alternative that convinces them. Personally, I think a switch (or a resolution of ambiguity as you call it) would probably be easy to execute and not cost too much.

JP: …Miles, here are the remainder of my thoughts.

On further thought, although it is great for crime-fighting, making everyone turn in their $100 and $50 bills by a given date may be seen as somewhat draconian. Saying that after a certain date the Fed will accept them only at a discount, that will gradually increase, then pick up speed is a nice way to both (a) do the elimination of high-denomination bills in a less draconian way and (b) get people used to the idea of exchange rates for paper currency.

I agree.

I routinely argue that up to something like a 4% paper currency deposit fee (which could easily be all that is ever needed, since -4% rates for 1 year are powerful enough to get a robust recovery in many countries), paper currency would probably be accepted at par at most retailers that deal in cash, since those retailers are now only getting about 96 cents on the dollar when people pay with American Express cards. Paper that yielded 96 cents on the dollar would look just as good.

That’s a good point. Are fees on Amex really that high? Wow! Since Mastercard and Visa are so much more ubiquitous than American Express – many won’t accept Amex – shouldn’t we be using MasterCard/Visa as the standard? Interestingly, Australia imposes maximum credit card fees that are quite low. They also allow retailers to apply surcharges, which looks something like this:

There is rumbling up in Canada that we might do the same. In any case, depending on its laws concerning credit card interchange fees, each nation could have its own peculiar negative interest rate trigger point at which paper currency prices will start to diverge from electronic prices.

There’s also the production, distribution, and wholesale side of the economy to consider, which doesn’t transact using credit cards. They use things like cheques or wire transfers, with very low handling fees relative to the size of the transaction. The e-money price and cash price could diverge quite quickly as a crawling peg is implemented.

But also, it really isn’t that big a deal if, say, paper is running at a 7% discount so that retailers no longer accept it at par at the cash register. That is no more complicated than a 7% sales tax at the cash register, which people don’t blink an eye at.

At 7% the lite programs wouldn’t work anymore. And if a -7% rate is what it takes to ensure the central bank is hitting its targets, then two different prices is the least of our concerns! In any case, from a purely tactical perspective, if you run into someone who disagrees with the crawling peg idea because it creates dual prices, and you can change their mind, that’s great – but if you can’t change their mind no matter how hard you try, the lite options provide a fall back.

Greg Shill: Does the Fed Have the Legal Authority to Buy Equities?

This is the second guest post by Greg Shill, a lawyer and fellow at NYU School of Law, on the legal scope of the Fed’s powers in the area of unconventional monetary policy. His work focuses on financial regulation, corporate law, contracts, and cross-border transactions and disputes, and his most recent article, “Boilerplate Shock: Sovereign Debt Contracts as Incubators of Systemic Risk,” examines the role of financial contracts in the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis. (His first guest post was “So What Are the Federal Reserve’s Legal Constraints, Anyway?”)

As a longtime follower of Miles’ work, it’s an honor and privilege to write for his blog and to put my ideas in front of his diverse and sophisticated audience. So, thank you, Miles, and your devoted readers.

I. For the past several years, the Federal Reserve has used many levers to stabilize and stimulate the economy. One of its most controversial has been the use of so-called unconventional monetary policy, chiefly three rounds of quantitative easing (or QE, beautifully explained in this clip) from 2008 to 2014. Although the wisdom of these policies has been widely debated, the Fed’s legal range of action largely has not. In fact, as I have noted previously, policymakers and observers have been remarkably quiet about the scope of the Fed’s legal authority to conduct unconventional policy, and when they do describe it they often offer timid visions of the Fed’s powers.

Economists and other observers have often urged the Fed to do more to juice a recovery that was, until recently, broadly disappointing. These proposals have included not only calls to cut interest rates and launch quantitative easing in the first place (both of which the Fed did), but to target higher inflation, introduce electronic money, conduct direct monetary transfers to the public, extend QE beyond its wind-down in October 2014, and expand the range of assets eligible for purchase under QE. The Fed of course did none of those more ambitious things, and today, with QE finished and policy normalizing, defining the legal limits on the Fed’s monetary policy arsenal may feel less urgent. Yet it is a startlingly important question to leave open, given the strong likelihood that the Fed will need to consider aggressive and creative measures in the future combined with the persistent overall weakness in the global economy.

The general question is: in a future recession or crisis, does the Fed have the tools it needs to go beyond what it’s done in the past? This is one of the most important open legal questions in public policy today.

II. Although it is not one of the sexier proposals mentioned above, in this post I will focus on the classes of assets the Fed can buy via quantitative easing. I start there because it’s an area where the scope of the Fed’s legal authority is unsettled, we are getting new data (foreign central banks are experimenting right now), and it seems like a somewhat politically plausible extension of the Fed’s recently retired QE campaign.

Under the Fed’s now-concluded QE program, the bank only bought U.S. treasuries and Fannie and Freddie mortgage-backed securities (“agency MBS”). Several of the Fed’s major overseas counterparts—including the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan—have embarked on their own QE programs, however, and in some ways they are already looking more ambitious. Japan is buying equities and the Europeans, who launched a massive QE program on Monday, have reportedly considered buying “all assets but gold.” If successful, broader asset-purchase programs like these could make it easier to contemplate an expanded purchase campaign by the Fed down the road.

Except for one minor detail: they are widely perceived as illegal under U.S. law. Former Fed official Joseph Gagnon has lamented that the Fed’s asset purchase authority “is limited by law to the Treasury, agency, and agency MBS markets plus foreign exchange” (emphasis added), and others agree. Gagnon would like the Fed to be able to “buy a broad basket of U.S. equities” (a view to which I am sympathetic), but he and others say that that idea lies beyond the Fed’s legal authority, namely the Federal Reserve Act of 1913.

Is it?

III. The argument that the Fed has the authority today to buy equities is not definitive, but is stronger than is currently acknowledged. Gagnon, an expert on monetary policy, maintains that “the Fed is not authorized to buy equities,” but to a lawyer, this statement is fraught with ambiguity.

True, the Federal Reserve Act does not expressly authorize the Fed to buy equities. Section 14 of the Act, titled “Open-Market Operations,” enumerates several categories of assets the Fed “shall have power” to buy—they actually extend beyond U.S. treasuries and agencies to include assets like gold, state and local government bonds, and foreign exchange—and equities is not among them.

Yet this does not really establish the outer bounds of the Fed’s authority to buy assets. The mere fact that a government agency lacks express statutory authorization to pursue a given policy does not necessarily render that policy illegal. Assuming no other provision of law forecloses that policy (and here, none does), it just means that to be legal, the Fed’s action would have to find a footing on another source—statutory interpretation, case law, a regulation—rather than the text of the statute itself.

The law provides a doctrine for navigating this type of uncertain administrative agency terrain. Known for the eponymous Supreme Court case, the Chevron doctrine gives us a two-part test for figuring out how much freedom of action federal agencies like the Fed enjoy where their governing statutes are unclear. Although the Federal Reserve Act has never been tested in this way, Chevron would provide some support for a decision by the Fed to buy equities (or, for that matter, private-label MBS).

Under Chevron “Step One,” a court asks whether the statute in question clearly circumscribes the agency’s discretion in a given area. If it does, then there is little analysis for the court to do (the agency either crossed the line or it didn’t), but if it does not, then Chevron “Step Two” applies.

Step Two: where the statute is unclear—in other words, the operative provisions are “silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue” at hand—the court asks whether the agency’s action “is based on a permissible construction of the statute.” Chevron v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837, 843 (1984) (emphasis added).

In the 31 years since Chevron was decided, the case has been interpreted thousands of times and has spawned an entire area of jurisprudence, but the essential question remains the same: was the agency’s interpretation of its own powers “permissible”?

IV. Note that the key question in the Chevron analysis is not whether the agency’s interpretation is the most legally sound or reflects the wisest policy choice. The court treats the ambiguity in the statute as a delegation of discretion by Congress to the agency to interpret the agency’s own powers; the court is only supposed to ensure that the agency reach an interpretation of those powers that is “permissible” (not even “reasonable,” let alone “best”).

Here, the operative statutory provisions are in the Fed’s legal mandate (Section 2A, “Monetary policy objectives”) as well as the open-market operations provision (Section 14). The mandate, which requires the bank to pursue full employment and price stability, is written at a high level; the bank is obligated to “maintain long run growth of the monetary and credit aggregates commensurate with the economy’s long run potential to increase production, so as to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates” (emphasis added). These terms are nowhere defined in the statute.

Assuming the Fed wished to begin buying equities, the basic interpretive exercise under Chevron would proceed as follows. We have here two provisions, Sections 2A and 14, that address monetary policy. Section 2A frames the overall objectives of the bank. Section 14 lists several types of assets the Fed can buy in open-market operations to pursue those objectives, but does not purport to restrict purchases to those types. Thus, there is a good argument that the scope of the Fed’s discretion to buy assets under Sections 2A and 14 is unclear, which satisfies Chevron Step One.

Under Step Two, the question would be whether the Fed’s equity buys were conducted pursuant to a “permissible” interpretation of the statute. This turns on questions of statutory interpretation that make even lawyers’ eyes glaze over, but the basic argument is straightforward: Section 2A is worded in such a way as to give the bank considerable discretion to pursue its goals, and Section 14 provides an illustrative, not exhaustive, list of the types of assets the Fed can buy. The Fed could argue that, under the circumstances, fulfilling the purpose of Section 14 requires adding equities to that list, or at least that doing so constitutes a “permissible” interpretation of the statute.

Such an interpretation doesn’t give the Fed carte blanche to buy whatever it wants, only those assets that it realistically thinks are consistent with the statute. So, for example, it could not buy California 10-year bonds, because Section 14(2)(b) expressly restricts the bank’s purchases of state government bonds to maturities not exceeding six months. But a regulation the Fed adopted long ago seems to contemplate the need for wiggle room beyond buying the assets enumerated in Section 14. It provides that the bank may “engage in such other operations as the [Federal Open Market] Committee may from time to time determine to be reasonably necessary to the effective conduct of open market operations and the effectuation of open market policies” (12 C.F.R. 270.4(d)).

This argument is not bulletproof. A second legal doctrine, this one from the area of statutory interpretation, seems to disfavor it: when one or more things in a class are mentioned by name, other members of the same class are implicitly excluded (this is known as expressio unius est exclusio alterius). However, the expressio unius canon does not yield a definitive interpretation either. It should be viewed as a way of getting at the underlying intent of the legislature rather than as a trump card wherever a law contains a list. For example, a sign stating that cars, trucks, and buses are allowed on a given bridge would not be read to preclude motorcycles from using the bridge. In fact, the bar on buying longer-maturity state government bonds suggests that Congress knew how to cabin the scope of the Fed’s authority and intended to specifically restrict the purchase of certain assets, but chose to leave the door open to buying other assets—not only, say, U.S. treasuries of longer maturities, but other classes of assets entirely. And of course if Congress had intended the Fed’s purchase authority to be limited to the assets specified in Section 14, it could have so limited that power. It didn’t.

So, it’s true that the Fed lacks affirmative authorization in the statute to buy equities, but the bank might have that power anyway.

V. Where does this leave us?

Substantively, the Fed probably enjoys greater discretion in unconventional monetary policy—possibly extending to the purchase of equities—than is commonly assumed. But an “equity QE” policy would benefit from an additional legal bulwark: the procedural maze our legal system subjects all litigants to.

A doctrine called standing would make it hard for a private citizen to mount an effective challenge to an equity QE program. This doctrine bars critics from bringing suit unless they can demonstrate a concrete, personal injury that is particular to them and that goes beyond ideological objections or the policy’s social effects. This is hard to impossible to demonstrate in the context of monetary policy. Specifically, a plaintiff seeking to challenge an equity QE program would have to show that he had been injured in some personal and tangible way, not merely that the value of his portfolio had declined (which presumably would also have happened to others pursuing a similar investment strategy). No investor has been able to show this type of injury with respect to the Fed’s aggressive bond-buying QE to date, and there’s no reason to think it would be easier to demonstrate such an injury from an equities purchase program. Combined with a stronger-than-recognized substantive legal justification, this bar on nettlesome litigation should make the likelihood of a successful legal challenge sufficiently dubious to give markets confidence that a Fed program to buy equities could proceed. That said, it would be preferable if the Fed had affirmative statutory authorization, but government frequently must act in a legal gray area.

Politics, of course, is one of the Fed’s most powerful constraints, and in the current political environment, monetary policy doves no doubt see reasons to downplay talk of the bank’s powers. However, hawks and other critics of the current Fed already seem very adept at using the bank as a political piñata without much regard for details like the precise scope of the Fed’s asset purchase authority (see, e.g., Rand Paul’s “Audit the Fed” campaign and legislation). Acknowledging that the bank probably has a wider legitimate range of action than it has used may help underscore the restraint the bank has observed to date. Regardless, it is important that the debate over Fed policymaking be conducted on the plane of policy rather than law. A better understanding of the scope of legal restrictions on the Fed will help facilitate and focus that conversation.

David Farnum: The Real (Estate) Cost of Student Debt

Many economic effects are complex. In the 6th student guest post this semester, David Farnum points out one of the more subtle costs of student debt:

The increase in student loans has lead students to increasingly make sub-optimal real estate investment and are forced to take relatively more expensive rentals.

The sentence above is actually an example of the requirement that my writing teaching assistant Adam Larson and I recently instituted that students write an explicit thesis statement at the top of their posts, in accordance with my dictum in “On Having a Thesis”

The thesis statement does not always have to actually appear in your post or essay, but it needs to exist and you need to know what it is.

Here is David’s argument for that thesis:

While the repayment of principal and interest on student loans themselves can be expensive, one of the hidden expenses is the opportunity cost of having this student debt amount, namely sub-optimal investment choices. One area of investment choices that are distorted due to accumulating student debt is in the real estate market: increased debt levels force recent graduates to forgo purchasing real estate assets. This impacts them on two fronts, first it limits their portfolio exposure to potentially lucrative investment returns and causes them to pay for relatively more expensive rentals.

As pointed out in A Random Walk Down Wall Street, an investment into hard real estate assets such as houses can provide excellent returns into a well diversified portfolio. Burton Malkiel explains:

As long as the world’s population continues to grow, the demand for real estate will be among the most dependable inflation hedges available. Although the calculation is tricky, it appears that the long-run returns on residential real estate have been quite generous…In sum, real estate has proved to be a good investment providing generous returns and excellent inflation-hedging characteristics.

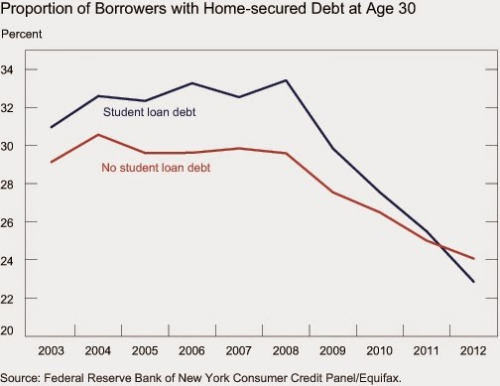

It makes sense that recent graduates would want to invest into such an asset class to better ensure they are able to take advantage of the long run returns that Malkiel describes. However, as more and more students are graduating with expanding college debt levels, they are increasingly unable to afford the purchase of a house. A 2013 post by Liberty Street Economistson the New York Fed blog analyzed the impact of student loans on home ownership. They explain their findings from the graph (below):

By 2012, the homeownership rate for student debtors was almost 2 percentage points lower than that of nonstudent debtors. Now, for the first time in at least ten years, thirty-year-olds with no history of student loans are more likely to have home-secured debt that those with a history of student loans.

In the past, those aged 30 with college debt were more likely to purchase a home due to their greater propensity to acquire higher paying jobs and thus be able to afford home ownership. However, this relationship has changed starting in 2012, possibly due to the higher overall levels of debt precluding mortgage approvals and reducing already debt burdened individuals ability to make home payments. The advent of this increasing proportion of students with debt and higher overall debt levels has been a contributing factor in the fall of home ownership, potentially leaving a large portion of recent graduates investment portfolios underexposed to the real estate sectors.

Not only are debt-burdened students under-investing in home ownership, they face increased relative prices for renting. A WSJ article entitled A Tough Time for Renters, outlines the rapid rise in rental prices:

The cost to rent an apartment jumped in 2014 for the fifth consecutive year as strong demand and short supply left vacancies at historically low levels. Nationwide, apartment rents rose an average 3.6% last year…the average monthly lease rate to $1,124.38, the highest since Reis started tracking the market in 1980.

A calculator provided by the New York Times allows one to compare the relative costs of renting vs home ownership based on a variety of input factors. Using the settings given, the equivalent home price to the national average monthly lease rate would be roughly $311,000. Given this is higher than the $199,600 national median sales price of existing homes, clearly the cost of renting currently greatly outpaced the cost of purchasing a home nationally.

However, the national data can skew the renting data, as rental rates will be especially high in areas of high populations such as large cities. Using a similar process to the NYT, online residential real estate company Trulia estimates the percentage difference in the cost of renting vs. buying a house in populous metropolitan areas. Their interactive map indicates that even in heavy populated areas, the cost of home is significantly less than that of renting, including a 21% difference in New York and Los Angeles, a 29% difference in Boston, and a 42% difference in Chicago.

All else being equal, this relative cost increase should tip the scales toward home ownership; however, as discussed above, the increased student debt levels have precluded individuals from home ownership. Not only are they missing out on the investment opportunity of real estate, they are throwing away relatively more money into the rental market.

Jonathan Zimmermann: The Quest for Uselessness

A large share of all the things that human beings want are things that are experienced in the mind. So it should not be too surprising that people will sometimes spend money or time on an idea that they find entertaining or humorous. Such was the pet rock craze a few years back. I was intrigued to learn that my student Jonathan Zimmermann accomplished such a feat of marketing an entertaining idea in a smaller way. His report on that is the 5th student guest post this semester. (Jonathan had another guest post a few weeks back that you might be interested in: “Swiss Franc Shock: Time to Take Advantage of Return Policies.”)

or the first time, Google Play (the Android app store) has surpassed the Apple app Store for the total number of published apps. Of course, among the almost one and a half million available applications, a lot of them, if not a majority, are of relatively little use. But usefulness is not a requirement for a successful app, as we saw for example many “fake razors” encounter a huge fame in the earliest days of the Apple app store. So what exactly is the limit of “uselessness”? How far could a developer go, and especially, do people need to at least believe that the app will be useful to want to download it? In this post I want to share my experience on an interesting experiment I conducted a few years ago.

It was a few years ago and I had just started to learn how to develop Android app. But coding wasn’t the part that interested me; I wanted to create, to publish. So I asked myself “What is the most simple, the most elementary app that I could develop and publish with my very limited newly acquired coding skills?”. The answer was easy: an app that doesn’t do anything. How would I call that app? “Useless”, because it has no features and is of no use. How to market it? Well, what is the only way to market nothing? Simply being honest and telling people not to expect anything from a nothing.

I published the app (still available with its description on Google play). I didn’t advertise it, and just waited for some organic traffic to come. In a few days, hundreds of people downloaded it. After a few months it had tens of thousands of downloads, for a total of more than 120 000 users today! Did I produce value? It seems like it: the average rating, by more than 4000 users, is 4.5/5, a very high rating for an Android app! But there is more: the ratio of review per download and the ratio of comment per review were extremely high!

Not only did the app satisfy its customers, but the average user seemed to be a relatively highly educated person. In one comment, a high school teacher even said he shared this app with his whole class.

Most positive comments looked something like that:

I love it, great job android market. This app has changed my life for the better. I used to wake up every morning crying, but now I have hope again. Finally something real, consistent, reliable, trustworthy. This app has shown me that there are things in the world that are truly what they claim to be. Simple, humble yet sophisticated. A Monk in the app, a world leader among its kind for having integrity. This app is a masterpiece. It is what it says, does what it’s supposed to do and comes with a 10×1 return policy.

by savage santana (edited)

So what about the people that didn’t like it? The only reason why it has a score of only 4.5/5 is that most users would either put the best rating (5) or the worst (1). Only a few would put an average rating, like 2, 3 or 4. And what were the reasons behind most of those 1-star ratings? Most of the time, they were written by unsatisfied customers that found some use in an app that what supposed to be useless:

I downloaded this app, with hope of finding no usefulness whatsoever, that hope was lost when I found it had many. I noticed the moment I opened the application, I had something to read. I enjoyed reading about how the creator of this app did not like how the Android Market had it’s name changed and the purpose of the apps creation. I also found how useful this would be for people who found it difficult to spell (Apart from some spelling mistakes). It also had enough light to see objects in the dark.

by Carl-Michael Hammon (unedited)

So think absurd, and don’t be afraid to be absurd. Downloading this app was perhaps, for some people, a right to be irrational for a few minutes. Sometimes, it feels good to not make sense. And this feeling is more logical than it seems.

And on a final note, for the capitalist skeptics who think that doing art is great but making money is better: do not worry, I didn’t lose my business acumen and carefully placed a discrete ad inside the app. It generated a few thousand dollars of revenues. Not too bad for a few hours of “programming”.

Christopher Skehan: Everyone Needs a Vacation

Link to Christopher Skehan’s LinkedIn Home Page

I am pleased to host this guest post by Christopher Skehan on the importance of vacations—even as compared to other business concerns (obviously related to Dan Miller’s case for the importance of sleep). It is the fourth guest post this semester from students in my Monetary and Financial Theory class. You can see links to all of the other student guest posts here. Here is Chris:

It’s no secret that everybody loves time off from work to go on vacation. It seems pretty simple that people should work to live, and therefore use all of their vacation time. Yet, American business culture produces employees imagining industriousness that includes first-in and last-out workers, all nighters, and long work sessions for consecutive weeks. For many there is no room for vacation in this industrious image. “More than forty percent of American workers who received paid time off did not take all of their allotted time last year, according to “An Assessment of Paid Time Off in the U.S.” commissioned by the U.S. Travel Association, a trade group, and completed by Oxford Economics” (Forbes). The U.S., one of the few developed countries that doesn’t require companies to provide vacation time, needs to change because taking a vacation is good for production and in some cases can even prevent crime.

This productivity science seems like a justification for laziness in the workplace. However, several scientific observations have proved that taking small breaks during long study sessions not only dramatically improves your productivity but also your mental ability. The theory is simple, the brain is a muscle, and every muscle tires from repeated stress. “In the mid-1920s, an executive in Michigan studying the productivity of his factory workers realized that his employees’ efficiency was plummeting when they worked too many hours in a day or too many days in a week” (The Atlantic). So if this is true on a micro level then it must be true on a macro level.

So far it is clear that taking breaks and by extension vacation are essential for employees, but does it hurt the employer? Quite the contrary, it has several advantageous for employers according to Forbes. First, when one employee leaves it forces an additional employee to learn the functions of a new job. This system creates an unintentional education system, and prevents the risk of crisis when a key employee is lost. Secondly, it cuts cost through reductions in health insurance payments. “The American Psychological Association has documented several potentially stress-induced health threats, such as increased cardiovascular risks and aggravation of existing conditions” (WSJ). Reducing health issues from your employees in not only the moral thing to do, but can now be justified in your balance sheets as well. Thirdly, mandatory vacation prevents fraud and embezzlement. “In 2007, Jérôme Kerviel, a trader at Société Générale, lost over $7 billion of the bank’s money. He later admitted hadn’t take one single day of vacation that year because he did not want anyone else to look at his books” (Forbes). For situations like this the FDIC has mandatory two-week vacation for certain industries.

The FDIC has the right idea but it needs to be implemented to every industry. During my time in Italy this last summer everything closed from one to three in the afternoon for people to go home and eat lunch with their family. When I explained to my host family that Americans didn’t do this they thought it was insane and called us robots. Now I think they are right, and think it is essential to implement mandatory vacation time for all employees. It reduces the cost of health insurance, increases productivity, produces a more trained workforce, and stops fraud.

John Stuart Mill’s Defense of Freedom of Religion for Mormons as an Argument for Chartering Libertarian Enclaves

Brigham Young’s family. Link to an overview of Mormon polygamy.

John Stuart Mill was no fan of Mormonism. But he defended the right of Mormons to practice plural marriage–something the US Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court in Reynolds v. United Statesdid not do. The argument he makes is that when a group has fled for refuge to an out-of-the-way corner of the Earth, freely allows outside missionaries to come preach against its barbarism, and freely lets people leave the group, then it should not be molested even in customs that seem barbaric. Here is his argument, from On Liberty, Chapter IV, “Of the Limits to the Authority of Society over the Individual” paragraphs 21:

I cannot refrain from adding to these examples of the little account commonly made of human liberty, the language of downright persecution which breaks out from the press of this country, whenever it feels called on to notice the remarkable phenomenon of Mormonism. Much might be said on the unexpected and instructive fact, that an alleged new revelation, and a religion founded on it, the product of palpable imposture, not even supported by the prestige of extraordinary qualities in its founder, is believed by hundreds of thousands, and has been made the foundation of a society, in the age of newspapers, railways, and the electric telegraph. What here concerns us is, that this religion, like other and better religions, has its martyrs; that its prophet and founder was, for his teaching, put to death by a mob; that others of its adherents lost their lives by the same lawless violence; that they were forcibly expelled, in a body, from the country in which they first grew up; while, now that they have been chased into a solitary recess in the midst of a desert, many in this country openly declare that it would be right (only that it is not convenient) to send an expedition against them, and compel them by force to conform to the opinions of other people. The article of the Mormonite doctrine which is the chief provocative to the antipathy which thus breaks through the ordinary restraints of religious tolerance, is its sanction of polygamy; which, though permitted to Mahomedans, and Hindoos, and Chinese, seems to excite unquenchable animosity when practised by persons who speak English, and profess to be a kind of Christians. No one has a deeper disapprobation than I have of this Mormon institution; both for other reasons, and because, far from being in any way countenanced by the principle of liberty, it is a direct infraction of that principle, being a mere riveting of the chains of one-half of the community, and an emancipation of the other from reciprocity of obligation towards them. Still, it must be remembered that this relation is as much voluntary on the part of the women concerned in it, and who may be deemed the sufferers by it, as is the case with any other form of the marriage institution; and however surprising this fact may appear, it has its explanation in the common ideas and customs of the world, which teaching women to think marriage the one thing needful, make it intelligible that many a woman should prefer being one of several wives, to not being a wife at all. Other countries are not asked to recognise such unions, or release any portion of their inhabitants from their own laws on the score of Mormonite opinions. But when the dissentients have conceded to the hostile sentiments of others, far more than could justly be demanded; when they have left the countries to which their doctrines were unacceptable, and established themselves in a remote corner of the earth, which they have been the first to render habitable to human beings; it is difficult to see on what principles but those of tyranny they can be prevented from living there under what laws they please, provided they commit no aggression on other nations, and allow perfect freedom of departure to those who are dissatisfied with their ways. A recent writer, in some respects of considerable merit, proposes (to use his own words) not a crusade, but a civilizade, against this polygamous community, to put an end to what seems to him a retrograde step in civilization. It also appears so to me, but I am not aware that any community has a right to force another to be civilized. So long as the sufferers by the bad law do not invoke assistance from other communities, I cannot admit that persons entirely unconnected with them ought to step in and require that a condition of things with which all who are directly interested appear to be satisfied, should be put an end to because it is a scandal to persons some thousands of miles distant, who have no part or concern in it. Let them send missionaries, if they please, to preach against it; and let them, by any fair means (of which silencing the teachers is not one,) oppose the progress of similar doctrines among their own people. If civilization has got the better of barbarism when barbarism had the world to itself, it is too much to profess to be afraid lest barbarism, after having been fairly got under, should revive and conquer civilization. A civilization that can thus succumb to its vanquished enemy, must first have become so degenerate, that neither its appointed priests and teachers, nor anybody else, has the capacity, or will take the trouble, to stand up for it. If this be so, the sooner such a civilization receives notice to quit, the better. It can only go on from bad to worse, until destroyed and regenerated (like the Western Empire) by energetic barbarians.

By this logic, the world should definitely allow some hard-core Libertarian enclaves to exist, somewhere. It seems unfair to me that there is no city in the world that people can go to and live under totally Libertarian rules. There isn’t even a city in the world where people can go and live under otherwise totally libertarian rules with the one compromise that they must continue to pay the taxes that they would otherwise have had to pay where they came from. One can question whether hard-core Libertarianism would work well as a governing principle for society, but it is a crime that people can’t try it out somewhere on earth.

Virginia Postrel: The Illusion of Living Without Illusions

“One job of intellectuals is to puncture glamour by reminding us of what’s hidden. But intellectuals are by no means exempt from glamour’s effects. They simply have their own longings and hence their own versions of glamour, including in some cases the ideal of a life without meaningful illusions.”

– Virginia Postrel, The Power of Glamour, p. 221

David A. Garvin and Joshua D. Margolis on Misjudging the Quality of Advice

“Most seekers who accept advice have trouble distinguishing the good from the bad. Research shows that they value advice more if it comes from a confident source, even though confidence doesn’t signal validity. Conversely, seekers tend to assume that advice is off-base when it veers from the norm or comes from people with whom they’ve had frequent discord. (Experimental studies show that neither indicates poor quality.) Seekers also don’t embrace advice when advisers disagree among themselves. And they fail to compensate sufficiently for distorted advice that stems from conflicts of interest, even when their advisers have acknowledged the conflicts and the potential for self-serving motives.”

– David A. Garvin and Joshua D. Margolis, subsection on “Misjudging the quality of advice” in “The Art of Giving and Receiving Advice,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2015, p. 64

Quartz #60—>The Coming Transformation of Education: Degrees Won’t Matter Anymore, Skills Will

Here is the full text of my 60th Quartz column, “Degrees don’t matter anymore: skills do,” now brought home to supplysideliberal.com. It was first published on February 9, 2015. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

Although I think the provocative title on Quartz helped get people to notice the column, I have what I think is a more accurate title above. This is my 2d most popular column ever. You can see the full list in order of popularity here.

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© February 9, 2015: Miles Kimball, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2017. All rights reserved.

If I were to make a nomination for the most destructive belief in our culture, it would be the belief that some people are born smart and others are born dumb. This belief is not only badly off target as a shorthand description of reality, it is the source of many social pathologies and lost opportunities. For example:

- Those who get low test scores think they are just not as smart and avoid tough majors that lead to some of the best jobs.

- A strong belief within an academic field that talent is innate goes along with that field having fewer women and African-Americans.

- Many people utter the black magic spell “I’m bad at math” and it becomes so. A lucky few have that spell broken, and find they can become good at math after all.

- People misunderstand the past and imagine a dystopian future, not realizing that each generation is smarter than the last.

Too much of our educational system, both at the K-12 level and in higher education, is built around the idea that some students are smart and others are dumb. One shining exception are the “Knowledge is Power Program” or KIPP schools. In my blog post “Magic Ingredient 1: More K-12 School” I gave this simple description of the main strategy behind KIPP schools, which do a brilliant job, even for kids from very poor backgrounds:

- They motivate students by convincing them they can succeed and have a better life through working hard in school.

- They keep order, so the students are not distracted from learning.

- They have the students study hard for many long hours, with a long school day, a long school week (some school on Saturdays), and a long school year (school during the summer).

A famous experiment by Harvard psychology professor Robert Rosenthal back in 1964 told teachers that certain students, chosen at random, were about to have a growth spurt—in their IQ. These kids did wind up having their IQ grow faster than the other kids. If we had an educational system that expected all kids to succeed, and gave them the kind of extra encouragement that those teachers unconsciously gave the kids they expected to do well, then kids in general would learn more.

Kids whose teachers had low expectations can expect more typecasting in college. Too many majors fall into one of two categories: (a) majors in which there is no easy way to tell whether a student has mastered any skills that will help get a job or make life richer, or (b) majors designed to weed out all the slow learners and only try to teach the students who catch on quickly. Behind the practice of weeding out slow learners is the misconception that a slow learner is a bad learner, when in fact a slow learner who puts in the time necessary to learn often ends up with a deeper understanding than the fast learner.

The good news is that a total transformation of education is coming, whether the educational establishment likes it or not. I draw my account of this transformation of education from two prophetic books by Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen and his co-authors:

- Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns by Clay Christensen, Curtis Johnson and Michael Horn

- The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education from the Inside Out by Clay Christensen and Henry J. Eyring.

The road ahead is clear: the potential in each student can be unlocked by combining the power of computers, software, and the internet with the human touch of a teacher-as-coach to motivate that student to work hard at learning. Technology brings several elements to the equation:

- customized lessons adapted to each student’s individual learning style at a cost that won’t break the bank

- lectures from some of the most talented instructors in the world (such as this course in financial asset pricing by the impressive John Cochrane and many other economics classes by Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok)

- the kind of software motivational tricks that make it so hard for kids to pull away from video games

- flexibility for students to learn at their own pace.

But since motivation—the desire to learn—is so important, a human teacher to act as coach is also crucial. In particular, without a coach, the flexibility for students to learn at their own pace can be a two-edged sword, because it makes it easy to procrastinate.

In the end, none of this will be hard. The technology and content for that technology are already good and rapidly improving. And although it is a bit much to expect someone to be both a great and inspirational coach and to be at the cutting edge of an academic field, the number of great athletic coaches and trainers at all levels indicates that, on its own, being an inspirational coach is not that rare. Being an inspirational coach in an academic setting is not quite the same thing, but I am willing to bet that it, too, is blessedly common. By having the cutting-edge knowledge from the best scientists and savants in the world built into software and delivered in online lectures, all a community college has to do to deliver a world-class education is to hire teachers who know how to motivate students.

Similarly, at the K-12 level, it is easier to find teachers who will be inspirational if those teachers can connect each student with expertly designed software customized for each student’s learning style. And teachers will be able to encourage each student to dig deeper into some particular interest that student has—well beyond the teacher’s own knowledge. Yet the teachers themselves will end up knowing a lot—much more than they learned in college themselves, simply from working alongside the students.

But what about all the forces arrayed against educational reform? Though they have won over and over in the past, those reactionary forces will be overwhelmed by these new possibilities. They will be like the corporate information technology department trying to stop workers from downloading unapproved, but inexpensive software on their own to get the job done.

The day is not far off (some would argue it is already here), when any parent who has the inclination to be a learning coach can team up with inexpensive online tools to give his or her child an education that is 20% better (say as measured by standardized test scores achieved) than what that child would get in the regular schools. It is hard to start a new charter school, and harder still to change a whole school district. But when an individual family can opt out, it is no longer David vs. Goliath in a duel to the death, but David leaving Goliath behind in the dust in a foot race. In the end, I think organized institutions can do a better job at teaching than parents on their own—but only if those institutions do things right. The ability of individual families to opt out will force most schools to get with the program, or lose a large share of their students.

None of this will happen instantly. In K-12, some states already have a strong tradition of educational reform, and will jump-start these changes. In other states, the forces arrayed against reform will be able to hold back progress for quite some time, by fighting tooth and nail against it. Rich, educated parents may help their kids tap into the new educational possibilities more quickly than poor parents who aren’t as attuned to education. But when performance gaps open wide enough, education in the laggard states will come around, by popular demand. And the scandal of ever more substandard education for the poor will encourage efforts by concerned citizens toward solutions empowered by the new learning technologies.

In higher education, students voting with their feet will make schools at the bottom of the heap change or die. Many of the most prestigious colleges and universities will resist change much longer, but some will embrace the “flipped classroom” model of doing everything online that can effectively be done online, and doing in the classroom only those things for which face-to-face interaction is crucial. And when some of the prestigious colleges and universities embrace the new methods, those colleges and universities will move ahead in the rankings as a result. The rest will ultimately follow.

There is one other force that will propel the transformation of education: a shift from credentials to certification. In most of the current system, the emphasis is diplomas and degrees—credentials saying a student has been sitting in class so many hours, while paying enough attention and cramming enough not to do too much worse than the other students on the exams. More and more, employers are going to want to see some proof that a potential employee has actually gained particular skills. So certificates that can credibly attest to someone’s ability to write computer code, write a decent essay, use a spreadsheet, or give a persuasive speech are going to be worth more and more. And any training program that takes the need to maintain its own credibility seriously can help students gain those skills and certify them for employers in a way that bypasses the existing educational establishment. Just witness the current popularity of “coding bootcamps.” That model can work for many other skills as well. For many students, that kind of certification of specific skills is a very attractive alternative to a two-year degree.

When this transformation of education is complete, K-12 education will cost about the same as it does now, but will be two or three times as effective. College education will not only be much more effective than it is now, it will also be much cheaper. There will still be a few expensive elite colleges and universities–these schools are not just providing an education, they are selling social status, and the opportunity to rub shoulders with celebrity professors. But less elite colleges and universities will find it hard to compete with the cheaper alternative of community college professor as coach for computerized learning. So the problem of college costs will be a thing of the past for anyone focused on learning, as opposed to social status. (Of course, if lower college costs are one side of the coin, lower college revenue is the other side. College professors as a whole are likely to have a lower position in the income distribution in the future than in the recent past, with premium salaries limited to a shrinking group of well-paid academic stars.)

Florida State University Psychology Professor K. Anders Ericsson studies expert performance, whether in sports, art, or academic pursuits. His research shows that ordinary people with extraordinary motivation can achieve remarkable performance through a pattern of arduous work and study called deliberate practice. By bringing computers and computer networks in to help with the other aspects of teaching, our society will be able to afford to focus on instilling in students that kind of extraordinary motivation. When that happens, the world will never be the same again.

Steven Landsburg: Big Price Fluctuations are Evidence of Competition

“A monopolist always has price-sensitive customers—because if they’re not price-sensitive, he’ll keep raising his prices until they are. Therefore, even when market conditions change, a monopolist can rarely afford to raise prices very much. Big price fluctuations are evidence of competition.”

– Steven E. Landsburg, More Sex is Safer Sex, p. 137. This is a fun piece of economics. Draw the supply and demand pictures and monopoly optimization pictures to see the logic here. There is wiggle room for this claim to not always be true, but Steven’s generalization has a lot of merit.

Negative Interest Rates and When Robots Will Set Monetary Policy: George Samman Interviews Miles Kimball

Link to the Article on cointelegraph.com. Mirrored by permission

Miles Kimball, who is a Professor of Economics and Survey Research at the University of Michigan tells CoinTelegraph about negative interest rates, the future of paper and electronic money, and how cryptocurrrency fits in.

Negative interest rates are a recent topic garnering much attention in the economic world. In no particular order, Denmark, Switzerland, Germany, Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Sweden have or have recently had negative interest rates. On top of that some corporate bonds have had negative interest rates as well like Nestle and Shell.

What are Negative Interest Rates?

Negative interest rates are when you give the bank or government some form of money, and over time that bank or government will give you back less money than you initially deposited.

Essentially, you are paying a bank or government to take care of your money. This is the result of a flight to safety for people who are extremely risk averse, and it generally happens coming out of a massive recession in places where there is little to no growth (e.g. the EU).

CoinTelegraph: Why is it easier to have negative interest rates with electronic money vs paper? Also can you explain how this would work with a currency like bitcoin vs. “electronic dollars”?

Miles Kimball: It is easy to have negative interest rates for money in the bank: the number for the balance in the account gradually goes down if nothing is put in or taken out. Because paper money has a particular number written on it, getting a negative or positive interest rate for paper currency requires a little more engineering. And that engineering involves having the e-dollar be the unit of account.

If the paper dollar were the unit of account, then the interest rate for paper currency is always zero (unless you have a system of directly taxing paper currency, which is administratively burdensome and politically much more difficult than an electronic money system). So to have negative interest rates on paper currency as well as in other assets, the e-dollar needs to be the unit of account.