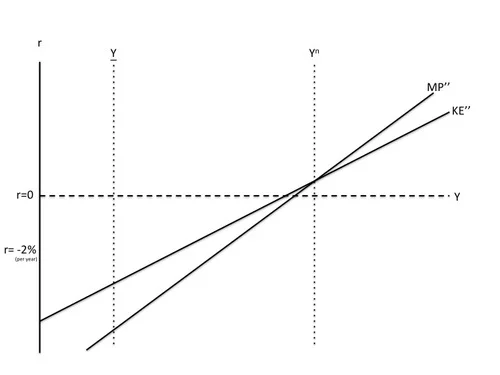

The slope of the KE curve shows how the perceived marginal efficiency of capital depends on the level of output. In addition to the KE curve having shifted down as a result of an increase in the risk premium (which has important irrational components) the risk premium pulls the marginal efficiency of investment down more when the economy is in a slump (a low level of output Y) and less when it is in a boom (a high level of output Y). In addition, as spell out for this framework in “The Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate and the Short-Run Natural Interest Rate,” it is more valuable to have extra capital when demand is high (a high level of Y) and less valuable to have extra capital when demand is low (a low level of Y). Both of these forces make the interest rate the central bank needs to choose to get the economy out of the slump quite low. And as JM Keynes suggests, a reduction in the perceived marginal efficiency of capital for any given level of output, which shows up as a shift downward in the whole KE curve, is often a precipitating force behind the slump in the first place. That gives a third reason it may require a very low interest rate for monetary policy alone to bring recovery. But as indicated by this graph, if the interest rate can go into deep negative territory there is no question that a low enough interest rate can bring the required economic stimulus. (The monetary policy curve “MP” specifies a very low interest rate when output is low. Although the level of output can still be low in the ultra-short run, for 9 months or so, this makes the natural level of output the only short-run equilibrium level of output.)

I have heard people say that no matter how low interest rates goes, it might not provide enough stimulus. But that is only because they have trouble imagining a world without the zero lower bound, in which the only thing limiting how far interest rates can go into subterranean depths is economic recovery itself. For many countries, the first thing that deep negative interest rates would do would be to cause a big increase in net exports, as the negative interest rates generated outward capital flows (see my post “International Finance: A Primer”). But that is in a situation in which that other countries have not yet broken through the zero lower bound, let’s discuss what would happen if all the major central banks went to deep negative interest rates during a worldwide slump.

In my column “Monetary Policy and Financial Stability,” I title a section

Monetary Policy Works Through Raising Asset Prices, Loosening Borrowing Constraints, or Affecting the Exchange Rate.

I just put aside the effect on exchange rates by assuming that the major central banks are following each other’s interest rates down (so that the gaps between different countries’ interest rates that matter most for international capital flows, exchange rates, and trade flows remain at their usual level). But the effect of low interest rates on asset prices is in full force.

Higher Asset Prices: Higher asset prices both raise the consumption of those who own those assets and make it easier to raise funds by selling assets. The main limitation on the rise in asset prices that people may believe recovery will come soon, so interest rates will be low only for a short time. But that belief itself would help bring recovery, so that is not a limitation to the power of monetary policy. So let’s dig deeper into the case where people remain very pessimistic.

Even if people are running scared, so risk premia are very high, low enough interest rates will raise asset prices, but it might well be that at first it the prices of the few assets perceived as relatively safe that go up noticeably. Let’s say for the sake of argument, that it is only US government bonds that go up in price. If the US government were acting like a business, that should induce more government investment spending. (See my column with Noah Smith “One of the Biggest Threats to America’s Future Has the Easiest Fix” and my post “Capital Budgeting: The Powerpoint File.”)

But suppose that for political reasons that doesn’t happen. As the central bank pushes the interest rate down further, some other asset will rise enough in price that more investment will begin. It might be house prices for existing houses that go up. That would ignite more house construction. It might at first be only extra construction of luxury homes. But that extra house construction would nevertheless begin to pull the economy out of the slump.

Now stack the deck against recovery more by supposing everyone has been so burned by a previous fall in house prices that they are unwilling to build new houses despite those high house prices. More generally, prevent refinancing of both mortgage and other household and business debt (much of which is short-maturity debt) by imagining a very high effective risk premium. Further, suppose that business investment also looks too dangerous. In that case, a set of assets whose price will rise is long-lived commodities. So, for example, employment in mining and geological exploration will increase. Of course, until this supply response has time to moderate the price movements the worldwide distribution of wealth will shift between those who have the long-lived commodities and those who need them will shift, but worldwide, there will be an increase in aggregate demand that makes it very difficult for the slump to persist.

The Storage Option: Now suppose none of that is enough to get the economy out of the slump. At some point, consumers, who otherwise would earn deep negative interest rates in the bank, will decide to get a better return through buying nonperishable goods and storing them for later consumption. They will think of what they are doing as “saving,” but in the national accounts it will be spending that adds to aggregate demand. This physical storage option puts a hard limit on how low interest rates can go without generating a large increase in aggregate demand.

The same storage option operates in the business sector. Currently, many businesses have a lot of liquid assets that they are just sitting on. If those liquid assets were all earning a deep negative interest rate, businesses would realize they could get a better return through buying ahead on materials and equipment they knew they would need in the future–or simply things they planned to resell in the future.

To the extent that some households and businesses have substantial liquid assets, converting any substantial fraction of those assets into durable or storable goods would amount to raising spending far above income in an accounting sense, implying a very strong addition to aggregate demand.

Note that for anyone who has liquid assets to begin with, the attractiveness of the storage option does not depend on being able to get a loan from a bank. And many people must have liquid assets, since any debt in the world–including the large debts of governments–is owed to someone else in the world.

“Broken Banks”: Businesses and banks sitting on idle piles of liquid assets is a telltale symptom of the zero lower bound. Breaking through the zero lower bound restores the functioning of banks. Given negative interest rates those piles of liquid assets (after perhaps earning an initial capital gain), face a low rate of return going forward if they are left in that form. So the banks have to do something. They might simply get involved in financing storage, perhaps through a wholly-owned subsidiary if they didn’t trust anyone else with those funds. And as noted above, storage of long-lived goods alone can bring recovery. But chances are the banks would begin thinking about making loans for regular forms of investment. And the subset of businesses that have their own piles of liquid assets would also begin thinking about using their own money to invest.

At the end of the day, low enough interest rates will bring recovery one way or another. If risk premia remained high enough, recovery could come through unusual channels, but it would come.

Taming the Financial Cycle as Well as the Business Cycle–Returning to the Natural Level of Output Does Not Mean Everything is Rosy: By “economic recovery” I only mean returning the economy to the natural level of output. Because risk premia are strongly affected by whether the economy is in a boom or slump–as well as by the risk of a future slump–keeping the economy at the natural level of output through vigorous monetary policy would greatly reduce problems stemming from fluctuations in the risk premium, but wouldn’t eliminate them. Dealing with the remaining “financial cycle” calls for other measures. The first is high equity requirements (implemented by a 50% capital conservation buffer) so financial institutions are playing with their shareholder’s money (equity) rather than depending on taxpayers to bail them out in a pinch. The second is a sovereign wealth fund. (My most recent post on that is “How and Why to Avoid Mixing Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy.” I collected links to my other posts on a sovereign wealth fund here.)

Why Not Just Do Everything Through Fiscal Policy Instead? I argue for the virtues of monetary policy over fiscal policy at length in my post “Monetary Policy vs. Fiscal Policy ….” To echo that post in brief,

- while adding to the national debt is not as serious an issue as some economists would lead one to believe (1, 2) it is not a thing of no consequence to add to the national debt.

- with the exception of automatic stabilizers–such as taxes automatically going down and transfers automatically going up when income goes down–it is not easy for countercyclical fiscal policy to be handled technocratically, because taxes and spending have too much resonance with the long-run issues that divide the major political parties in most advanced countries.

- technocratic countercyclical credit policy (which falls somewhere between monetary and fiscal policy) may be possible. The best implementation involves some form of required saving by households in good times with the ability to draw on that saving in a documentable personal emergency or in a recession.

Answering Tomas Hirst

Having set the stage with the long discussion above, it is time to answer Tomas more directly.

What if Negative Rates Cause an Increase in the Risk Premium? Tomas is in agreement with what I write in “On the Great Recession,” until this point in his post “Negative Rate Shocks.”

Firstly, I think there is the issue of what we can know about the risk premium. It is possible, though not unproblematic, to establish “the gross rental rate of capital R net of the depreciation rate δ”, which would give us the non risk-adjusted KE curve. The risk adjustment, however, depends upon the demand outlook that has been thrown into uncertainty by the shock.

At the point of an economic shock squeezing the real interest rate by sharply dropping deposit rates could have the same effect as the fiscal authorities reducing automatic stabilisers. That is, an assumed support for demand would be removed causing a deterioration in the short term demand outlook. This in turn increases the necessary risk adjustment to the net rental rate and would force monetary authorities to push rates even lower.

If this analysis is right then the act of lowering rates below zero may be a causal factor driving the risk premium higher such that, even though it is not infinite, the real world experience of it under monetary dominance may appear just as if it was. Were investors to react to a central-bank-induced negative rate shock this way then the result could actually be to reduce risky investment even more.

On the Keynesian view, there is a large irrational component to the risk premium. Although I don’t know how big the irrational component of the risk premium is, I suspect it is substantial, and I worry about it. To the extent there is an irrational component to the risk premium, it is possible that it behaves in the way that Tomas suggests. But unless the risk premium increases more than 1-for-1 with declines in the interest rate into negative territory, lower the interest rate will still result in more stimulus. Even if a more than 1-for-1 increase in the risk premium overwhelms the decline in the interest rate at first, it is very unlikely that the risk-premium would respond in a more than 1-for-1 way beyond a certain point. There is likely to be an effective maximum to the risk premium, at least for some projects for which likely outcomes are especially easy to calculate. Storage is one type of project for which the likely outcome is easier to calculate than for more complex investments. But there are bound to be other investment projects for which the outcome has only so much uncertainty to it. No matter how large, any finite level of perceived risk can be overcome by a low enough interest rate.

The most likely side effect of negative interest rates in a bad case is that the channels of stimulus that start to work first are not the most desirable ones. But they will work. And once the economy returns to the natural level of output, the composition of aggregate demand is likely to normalize. (More regular people will have jobs and feel enough confidence to begin spending. More regular businesses will have customers, and feel enough confidence to begin investing.)

In saying all of this, it is important to point out that to deal with the worst case scenario I am assuming a resolute central bank that understands this logic. In the real world, I believe that even a pioneering, but still feckless central bank that went to a minus -1.5% interest rate and wasn’t prepared to go any further down would see enough of a kickstart to aggregate demand that things would soon be headed in a positive direction. To understand that claim, it is important to realize that the first central bank to break through the zero lower bound would get the increase in aggregate demand from an increase in net exports since the other central banks would not yet be prepared to follow it down with their own target rates. It would only be after negative interest rates got the reputation for working in this way, that the other issues I raise above come into play. So by the time enough of the major central banks are using negative interest rates that the stimulus channel through net exports is cancelled out, negative interest rates would have a reputation for working that is likely to persuade many of the irrational economic actors.

This net export effect of negative interest rates is nicely analogous to going off the gold standard during the Great Depression. During a major slump, going off the gold standard allows an increase in the money supply and so is helpful even when all nations do it. It is not just a zero-sum game. But the fact that the first countries to go off gold got an extra boost to aggregate demand from an increase in net exports helped persuade other countries to go off gold, and helped investors believe that going off gold would help.

What If Investors Shift Into Alternative Safe-Haven Assets? In his post, Tomas continues with a comment of Francis Coppola:

My colleague, Frances Coppola, suggests a further problem. Faced with negative nominal rates investors could be tempted to abandon interest-bearing instruments all together and rush into alternative safe haven assets. These could be traditional assets like gold or other commodities (potentially including digital commodities such as crypto-currencies e.g. Bitcoin).

As I have argued above, the rise in asset prices would still eventually raise aggregate demand. More gold mining is to me one of the worst forms of aggregate demand, but it still provides some stimulus. The net export channel arises from pouring investable funds into foreign assets. And it is important to remember that anyone who buys assets puts money into the hands of the one selling those assets. That seller then has to do something with that money. So a rise in the price of assets doesn’t absorb and “use up” the stimulus. Rather, it ultimately reflects the stimulus back onto the real economy. In an initially tough economy, the rise in asset prices might be much more striking than the improvement in the real economy, but both will be there.

What If Negative Interest Rates Increase Perceived Interest-Rate Risk? Finally, Tomas writes:

Moreover, investment may be made in the present but it necessarily incorporates expectations about the future. Lowering the discount rate by pushing down the risk free rate leads to greater uncertainty around the net present value of investment opportunities. Lowering r means a lower discount of the future, which implies more uncertainty about the future is priced into current asset values. (My thanks to @richdhw for that one)

Increasing uncertainty over the future value of investment opportunities could discourage companies from committing money to new projects, especially if the short-term demand outlook remains highly uncertain.

I take this to say that large movements in interest rates can themselves cause a great deal of uncertainty and raise risk premia. But the possibility that interest rates might be very low (in real terms), can only raise the value of an asset. Breaking through the zero lower bound doesn’t do anything to raise the upper end of plausible values of the real interest rate.

To see the logic here, suppose I told you that your chances of failure in a business venture were the same, but that now, in addition to the possibility of modest success, you now had a significant chance of truly striking it rich. This new upside risk raises the variance of the possible outcomes you face, so it could indeed raise the risk premium. But by raising the mean return as well, it has to raise the overall attractiveness of the business venture! Similarly, for a straightforward investment project, increasing the chances for very low (real) interest rates at the bottom end while keeping unchanged the likely possibilities for interest rates at the high end can only increase the present value of that project.

What If Uncertainty about the Course or Effectiveness of the New Policy Induces a Wait-and-See Attitude on the Part of Firms? For those who think that uncertainty will cause firms to wait and see what will happen next (which I suspect includes Tomas, given his other comments), let me point out that all along in “The Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate and the Short-Run Natural Interest Rate,” and “On the Great Recession,” I am working primarily with the delay condition: under what circumstances will a firm choose to delay investing until next year. If a large amount of uncertainty will be resolved between this year and next, that is a powerful force making a firm want to delay investment in a wait-and-see mode. But a low interest rate is a powerful force making firms want to invest sooner–one that can overwhelm any wait-and-see motivation, if the central bank continues to feel for the interest rate that will restart investment.

Conclusion: The Long-Run Benefits of Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound: The graph I used in “Janet Yellen is Hardly a Dove—She Knows the US Economy Needs Some Unemployment” to show the Great Moderation between the mid-1980’s and the beginning of the Great Recession indicates some of the benefits I expect from eliminating the zero lower bound: