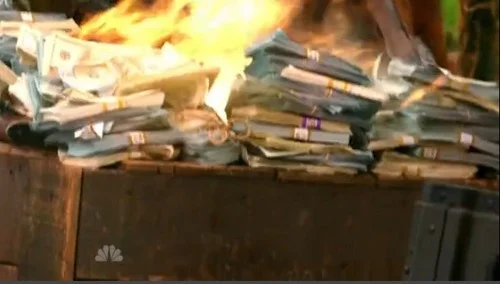

When Raymond Reddington (played by James Spader) burns a pile of US paper currency in the second season opening of “The Blacklist,” he is giving a gift to the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”), and through the Fed, to the US government. To see this, notice that right after the US paper money is burned, the Fed can ask the US Mint to print an equal amount of paper currency for its vaults, and other than the cost of the paper and ink themselves, get the same result as if Raymond Reddington had given the paper currency directly to the Fed. This would be income to the Fed, and unless the Fed increased its expenses, would ultimately be added to the check that the Fed sends to the US Treasury every year.

Similarly, if the Fed mails money to every US citizen, instead of using the money it creates to buy US Treasury bills, as it usually does, then the US Treasury ends up selling those bonds to someone else and the US government ends up owing that amount to someone else who won't ultimately send the interest it earns back to the US Treasury as the Fed does.

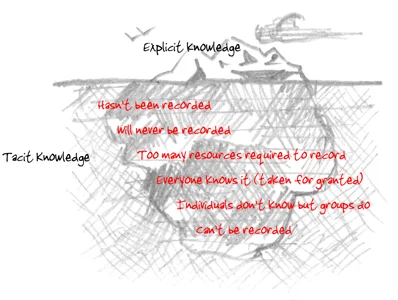

Indeed, if the Fed mails every citizen money–a so-called “helicopter drop”–it is equivalent to the Fed doing its usual thing of buying US Treasury bills, plus the US Treasury issuing treasury bills to finance sending money to every citizen. The reason treating a helicopter drop as the combination of these two operations is useful is that the first (the Fed buying US Treasury bills) is the normal way that the Fed changes interest rates (when the zero lower bound doesn’t get in the way), while the second (the US Treasury selling bonds to finance sending money to every citizen) brings in all the complexity of fiscal policy. In the present, it takes money from those who buy the new bonds (who presumably like to save) and gives it to all the citizens (among whom there are some who like to spend). From a long-run perspective, having the US Treasury sell bonds to finance sending money to every citizen takes money from future taxpayers, in proportion to who would be asked to pay extra future taxes, to spread it out relatively evenly to citizens now. So there is redistribution. And the overall amount of redistribution that takes place through fiscal policy is an object of fierce debate between the major political parties.

I think the debate about how much redistribution should take place should be carried out in as open and transparent a way as possible. But if there are to be any obfuscations in this area, leave the Fed out of those obfuscations! If you think it is a good idea to mail money to every citizen, let the US Treasury do it; then no one will mistake what is going on, and the argument can be in the open.

Now, when the economy needs stimulus, and monetary policy is seriously constrained in a way that can’t be helped, mailing a credit card to every citizen with a $2000 line of credit as I have advocated is somewhere between regular fiscal policy and regular monetary policy, and might be appropriate to put under the Fed’s jurisdiction. Such a policy strives not to redistribute, though it unavoidably does to some degree when some fraction of people fail to repay the loan from the government.

In addition to thinking that arguments about redistribution should be out in the open (as they are on my blog), I think it is important that the Fed be shielded from politics as much as possible in order to allow it to do its job of economic stabilization (keeping output at the natural level as that natural level shifts around in response to technological progress, and keeping the price level steady). That is why I argued in my column “Why the US Needs Its Own Sovereign Wealth Fund” that instead of having the Fed engaged in “quantitative easing,” buying anything other than 3-month Treasury bills should be left to another, new government agency:

… isn’t it a bit much to expect the Fed to both choose the right amount of stimulus for the economy and decide which financial investments are the most likely to turn a profit for a government that faces remarkably low borrowing costs?

Why not create a separate government agency to run a US sovereign wealth fund? Then the Fed can stick to what it does best—keeping the economy on track—while the sovereign wealth fund takes the political heat, gives the Fed running room, and concentrates on making a profit that can reduce our national debt.

I collected links to other posts I have written about sovereign wealth funds as an instrument of economic policy here.

Through Roger Farmer, who also endorses sovereign wealth funds as an instrument of economic policy, I heard about Mark Blythe and Eric Lonergan’s plan, heartily endorsed by Matt Miller, to either (a) mail money to consumers, or (b) earn returns through the central bank acting as a sovereign wealth fund and then send the funds earned out to people:

Central banks could issue debt and use the proceeds to invest in a global equity index, a bundle of diverse investments with a value that rises and falls with the market, which they could hold in sovereign wealth funds. The Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Federal Reserve already own assets in excess of 20 percent of their countries’ GDPs, so there is no reason why they could not invest those assets in global equities on behalf of their citizens. After around 15 years, the funds could distribute their equity holdings to the lowest-earning 80 percent of taxpayers. The payments could be made to tax-exempt individual savings accounts, and governments could place simple constraints on how the capital could be used.

Of these two ideas, I think the second, (b) is better. The money for redistribution is coming not from raising taxes but from having the government do risk bearing it is actually rewarded for, instead of through implicit risk guarantees that benefit private, often wealthy individuals.

However,

- I think it is much better institutionally to separate the sovereign wealth fund from the central bank. A sovereign wealth fund, though immensely valuable, is inherently controversial. The Fed and other central banks face enough controversy even when they don’t act as sovereign wealth funds. They don’t need the added political burden.

- Although I like the idea of new revenue that doesn’t come from taxes being used for some form of redistribution, it is not clear to me that sending people money is the best form of redistribution. There should be a vigorous debate about the most effective ways to lift up the poor for a given amount of money used. This is the issue I have with basic income proposals as well. Are they really the most effective ways to help the poor per dollar spent? (For example, see 1 and 2.)

Still, I am glad to see the idea of a sovereign wealth fund gain traction–not only

- as a way to stabilize the financial cycle–which would continue to exist even if the Fed completely tamed the business cycle, other than those fluctuations that are an appropriate response to technology and other real shocks–but also

- as an alternative way to add to government revenue on average without resort to taxes.

Notice that in the background I have a particular view on the rational level of risk aversion, which I plan to defend in a future post–though it is always hard to find time to write major, relatively technical posts.

I also want to be clear in saying that, after eliminating the zero lower bound (as it should), a central bank should only raise the amount of revenue that is consistent with maintaining zero inflation in the unit of account (except for a bare minimum of hard-to-avoid short-run fluctuations in inflation). In particular, inflation is a very costly way to renege on the promises a government makes when it issues bonds. That seems like a bad idea to me.