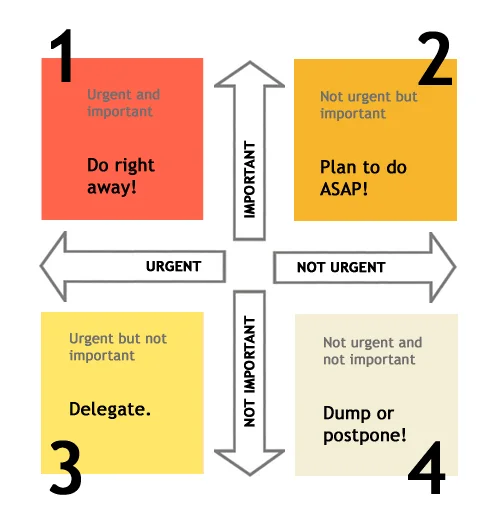

Prioritization

In my post “Debora Spar on the Dilemma of Modern Women,” I wrote

If you think “setting priorities” is a pleasant platitude, you don’t understand what it really is. “Setting priorities” is the brutal process of deciding which things won’t get done.

This is actually something I could use some help with. Recently, I read the Harvard Business Review article “Find the Coaching in Criticism” by Sheila Heen and Douglas Stone. Like many Harvard Business Review articles, it is of high quality (and unfortunately, that high quality doesn’t come for free–it is supported in part by the revenue generated through the Harvard Business Review's paywall.) They write:

Feedback is less likely to set off your emotional triggers if you request it and direct it. … Find opportunities to get bite-size pieces of coaching from a variety of people throughout the year. Don’t invite criticism with a big, unfocused question like “Do you have any feedback for me?” Make the process more manageable by asking a colleague, a boss, or a direct report, “What’s one thing you see me doing (or failing to do) that holds me back?” That person may name the first behavior that comes to mind or the most important one on his or her list. Either way, you’ll get concrete information and can tease out more specifics at your own pace.

I feel that I already get plenty of advice on things I should be doing more of–both for my academic career and for my career as an economic journalist (which is how I categorize my efforts on this blog). What I could use more of is advice on what I should be doing less of–things that I am putting time and effort into that don’t have an adequate payoff. To clarify, I need to say that I have three goals:

- to carve out a reasonable amount of leisure time, especially time with my family,

- to maintain my income track, and

- to make the world a better place, both in the short-run and in the long-run.

Both my academic career and my career as an economic journalist contribute to both goals, but in different degrees. My academic career is still at least an order of magnitude more important in providing income than my career as an economic journalist. (Any change in that fundamental fact would be a change that would look dramatic to outside observers as well as me.) But I feel my career as an economic blogger/journalist is at least as important as my academic career in making the world a better place. So I definitely want to keep up with both my academic career and my career as an economic journalist. But what I do within each of those categories, and the exact balance between them, is something I could use advice on.

Notice that in both academia and in blogging/journalism, a certain amount of self-promotion and institutional promotion is optimal. If I manage to write something worth reading, it is worth putting forth a certain amount of effort to get 5000 people to read it instead of 500. And some aspects of promotion of a blog are cumulative over time. I see the goal of having at least one post a day in that category. Even during a stretch where no one post is a big hit, it means something to readers to know there will be something every day.

All of that is just meant to direct you away from some possibly tempting, but I think, misguided pieces of advice like “Quit watching TV” (What? Reduce my leisure time further and lose my chance to enjoy the premier art form of our time?) or “Quit doing your blog” or “Abandon your academic career and become an economic journalist full-time.” By contrast, three pieces of feedback I have received, which may or may not be the right advice, but are definitely the kind of thing I am looking for, are “Twitter beyond basic announcements of posts and maybe one more tweet a day isn’t worth the time it takes if the goal is blog promotion,” “You don’t need to copy over the whole text of a post to Facebook, the link alone is plenty,” or “Reading and commenting on 200 blog posts from your students in the course of a semester is above and beyond the call of duty.”

In addition to getting your advice for myself, I wanted to recommend that those of you who feel you are overextended and overly busy also consider asking those around you

What should I be putting less time and effort into? What do think I am doing that isn’t worth the time and effort I put in?

To get useful responses, you might need to spell out your objectives clearly as I tried to do above for myself.

Cast your minds back, to a time when everyone supposedly loved each other. By MichaelH

Econlolcats on my blog are a sign of good things to come. Sometime this morning, I expect to have my latest column appear on Quartz. This one is on “Odious Wealth.”

"The Costs and Benefits of Repealing the Zero Lower Bound … and Then Lowering the Long-Run Inflation Target" in Japanese: ゼロ下限を無効にする費用と便益…そして長期インフレ目標を下げる →

The link above is to the Japanese version. “The Costs and Benefits of Repealing the Zero Lower Bound … and Then Lowering the Long-Run Inflation Target” in English can be found here.

Noah Smith: Judaism Needs to Get Off the Shtetl

I am delighted to be able to host another guest religion post by Noah Smith.

Don’t miss Noah’s other religion posts on supplysideliberal.com:

- God and SuperGod

- You Are Already in the Afterlife

- Go Ahead and Believe in God

- Mom in Hell

- Buddha Was Wrong About Desire

The point of this one is that it would great if more people in the world were Jewish. Let’s give people a chance to become Jewish by letting them now how easy it is to join Reform Judaism. (Note that you don’t have to be Jewish yourself to give people this useful bit of information.)

To me, Reform Judaism in particular is an important religion because it is one of the rare religions that fully welcomes non-supernaturalists.

Scott Aaronson has a wonderful blog about math and computer science, called “Shtetl-Optimized”. I’m not sure why it’s called that, since the name has nothing to do with the blog (which you should check out if you are a hardcore nerd). But anyway, this post is about the name, not the blog, since the phrase “shtetl-optimized” got me thinking about Judaism.

I was raised Jewish, but gently set it aside when I grew up and lost my taste for life rules for which I couldn’t see a point (e.g. “Don’t mix milk and meat!”). But I still think there is a lot to be valued in Judaism - as there is in most major religions - and I am mildly frustrated by the failure of these good things to diffuse out into the wider world. You see, the Jewish religion is still shtetl-optimized.

A shtetl was a Jewish ghetto in Central or Eastern Europe, similar to the town featured in the musical Fiddler on the Roof. Modern Judaism developed much of its current mix of ideas and culture in those little ghetto towns. These are precisely the elements that I think much of the world would embrace: 1) a love of knowledge, education, and friendly argument, and 2) a concept of personal morality based on healthy living and positive personal relationships.

Of course, these things have naturally diffused into modern culture to some extent, through American academia and Hollywood (two institutions in which Jews have a large presence). But I think people in many countries would enjoy being able to have a religion that emphasized these things on a daily basis, and provided the kind of cultural community that religions are good at providing. In other words, I think a lot of people in a lot of countries would enjoy being Jewish.

Unfortunately, they don’t get the chance. Most people don’t realize that it is very easy to convert to Reform Judaism (the less strict flavor, which doesn’t make you wear a funny hat). They don’t realize that because Jews consciously avoid making them aware of this fact. Jews, you see, have a cultural taboo against proselytizing. When I suggested to my (more religiously inclined) cousins that Jews should accept more converts, they were horrified.

Making people aware of the ease of conversion is actually not the same as “proselytizing”. “Proselytizing” means trying to convince people to convert. But my bet is that in the Old Country of Europe, the Christians who surrounded Jews failed to see that fine distinction. My guess is that if there was any rumor that the local Christians were converting to Judaism, then some Jewish people’s houses were going to get burned.

So my guess is that Jews learned their insularity on the shtetl. The cultural taboo against informing people in China, or Brazil, or Indonesia that they can be Jews if they want is an anachronism. If Judaism is to survive, much less bring the benefit of its unique perspective to those who would enjoy it, it’s going to have to learn to inform the goyish (non-Jewish) world that they, too, can be Red Sea Pedestrians.

(Of course, there are a few Jews who are insular for a quite different reason - they want to preserve the purity of the Ashkenazic race - an ethnic group that is mostly Jewish. I myself belong to that group, but to me, preserving the purity of the Ashkenazic race sounds about as desirable a goal as giving myself a vasectomy with a Dremel.)

Anyway, the upshot is this: Jews, time to get off the shtetl! There are lots of people in China and Brazil and Indonesia who would love to join your religion. Why not let them know they can?

Brad DeLong Quotes John Maynard Keynes to Defend the Neoclassical Synthesis Against Joseph Stiglitz →

I agree with Brad here. In Keynes vs. Stiglitz, I’ll go with Keynes.

Paul Finkelman: The Monster of Monticello →

Paul Finkelman argues persuasively in the New York Times op-ed linked above that Thomas Jefferson’s racism and his proslavery attitudes should not be whitewashed. In this area, he was far worse than many of the other founding fathers. Here is a key passage of Paul’s essay:

…the third president was a creepy, brutal hypocrite.

Contrary to Mr. Wiencek’s depiction, Jefferson was always deeply committed to slavery, and even more deeply hostile to the welfare of blacks, slave or free. His proslavery views were shaped not only by money and status but also by his deeply racist views, which he tried to justify through pseudoscience.

It is quite possible that the Civil War itself can be laid at Thomas Jefferson’s feet. Paul Finkelman writes:

Jefferson also dodged opportunities to undermine slavery or promote racial equality. As a state legislator he blocked consideration of a law that might have eventually ended slavery in the state.

As president he acquired the Louisiana Territory but did nothing to stop the spread of slavery into that vast “empire of liberty.”

If slavery had withered away in Virginia and there had been no slave states in the Louisiana territory, there is a good chance the proslavery forces would have lost political power early enough that things would not have escalated into the Civil War. Or even if there were a Civil War, if Viriginia had become a free state, perhaps Robert E. Lee’s loyalty to Virginia would have led him to lead Union troops into battle, and so to a much quicker end to the war.

Thanks to John L. Davidson for flagging this essay.

For my take on the biggest collective moral issue of our time, see “The Hunger Games is Hardly Our Future: It’s Already Here.”

For a bit of alternate history speculation about more recent events, see my post “Sliding Doors: Hillary vs. Barack.”

I have two posts on the more positive side of Thomas Jefferson: “Thomas Jefferson and Religious Freedom” and “The Importance of the Next Generation: Thomas Jefferson Grokked It.”

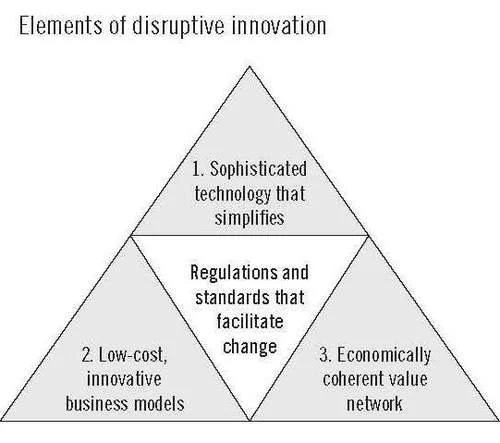

Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on How the History of Other Industries Gives Hope for Health Care

Image from The Innovator’s Prescription, location 294

Things start hard and then get easier. This can be true even for health care. Here are the examples that Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang give in The Innovator’s Prescription:

The problems facing the health-care industry actually aren’t unique. The products and services offered in nearly every industry, at their outset, are so complicated and expensive that only people with a lot of money can afford them, and only people with a lot of expertise can provide or use them. Only the wealthy had access to telephones, photography, air travel, and automobiles in the first decades of those industries. Only the rich could own diversified portfolios of stocks and bonds, and paid handsome fees to professionals who had the expertise to buy and sell those securities. Quality higher education was limited to the wealthy who could pay for it and the elite professors who could provide it. And more recently, mainframe computers were so expensive and complicated that only the largest corporations and universities could own them, and only highly trained experts could operate them. (We will come back to this last example, below.)

It’s the same with health care. Today, it’s very expensive to receive care from highly trained professionals. Without the largesse of well-heeled employers and governments that are willing to pay for much of it, most health care would be inaccessible to most of us.

At some point, however, these industries were transformed, making their products and services so much more affordable and accessible that a much larger population of people could purchase them, and people with less training could competently provide them and use them. We have termed this agent of transformation disruptive innovation. It consists of three elements (shown in Figure I.1). Technological enabler. Typically, sophisticated technology whose purpose is to simplify, it routinizes the solution to problems that previously required unstructured processes of intuitive experimentation to resolve. Business model innovation. Can profitably deliver these simplified solutions to customers in ways that make them affordable and conveniently accessible. Value network. A commercial infrastructure whose constituent companies have consistently disruptive, mutually reinforcing economic models.

Using some terminology Clay Christensen uses in all of his books, the key problem with health care is that so much of it is set up on the “solution shop” business model. The “solution shop” business model is familiar to academics in research universities because the kind of research done in academic is almost always done in a solution-shop way, by specialized crafting of ways to get a scientific job done. The only way to make health care significantly cheaper is to routinize and “deskill” or at least “downskill” much of it so that the job for at least the easy cases can be done in a way that is more in the spirit of mass-production: as a “value-added process.”

“Most people out there have a plan A. Successful people have a plan A, B, C, and D–that’s the key to life.”

– Mark Stevens, businessman and business writer, as quoted in Clutch, by Paul Sullivan.

"On the Great Recession" in Japanese: 大不況について →

The link above is to the Japanese version. “On the Great Recession” in English can be found here.

"America’s Big Monetary Policy Mistake: How Negative Interest Rates Could Have Stopped the Great Recession in Its Tracks" in Japanese: アメリカの金融政策の大きな過ち:そのとき、どうして負の利子率なら大不況を止められたか →

The link above is to the Japanese version. “America’s Big Monetary Policy Mistake: How Negative Interest Rates Could Have Stopped the Great Recession in Its Tracks” in English can be found here.

"How Subordinating Paper Money to Electronic Money Can End Recessions and End Inflation" in Japanese: 紙のお金を電子マネーに従属させることが不況をどう終わらせインフレーションをどう終わらせるのか →

The link above is to the Japanese version. “How Subordinating Paper Money to Electronic Money Can End Recessions and End Inflation in English can be found here.

Charles Lane on Thomas Piketty and Henry George

Link to Wikipedia article on Henry George

Charles Lane compares Thomas Piketty to Henry George in hi May 15, 2014 Washington Post op-ed,

Thomas Piketty identifies an important ill of capitalism but not its cure.

Charles gives a succinct evaluation of both Thomas’s and Henry’s proposals:

Alas, Piketty’s global wealth tax and George’s single tax suffer from the same defect, and it’s not political impracticality — after all, George nearly got himself elected mayor of New York City in 1886.

It’s the inherent difficulty of separating the productive, untaxed component of the return on land or capital from the unproductive, taxed part. …

As a result, it’s hard to devise a tax on wealth that raises a significant amount of revenue but doesn’t discourage at least some socially beneficial saving or entrepreneurship. The potential for adverse unintended consequences — economic and political — is greater than Piketty seems to realize.

Quite distinct from this concern about incentives, Charles goes on to a positive note about having power in the hands of private individuals:

Great private fortunes can indeed entitle their owners to an undue share of society’s current income and political power. At times, however, private wealth can serve as a font of charity or, indeed, a bulwark against government overreach.

These are indeed the key issues to think about in relation to wealth taxation.

I have always liked Henry George’s proposal, and pointed out how a carbon tax can be seen as akin to Henry George’s single tax in my post “‘Henry George and the Carbon Tax’: A Quick Response to Noah Smith.” And I like Noah’s application of Henry George’s idea to San Francisco. But Thomas Piketty himself points to the difficulty of getting enough revenue from taxing the value of unimproved land alone:

In particular, it seems impossible to compare in any precise way the value of pure land long ago with its value today. The principal issue today is urban land: farmland is worth less than 10 percent of national income in both France and Britain. But it is no easier to measure the value of pure urban land today, independent not only of buildings and construction but also of infrastructure and other improvements needed to make the land attractive, than to measure the value of pure farmland in the eighteenth century. According to my estimates, the annual flow of investment over the past few decades can account for almost all the value of wealth, including wealth in real estate, in 2010. …

… the fact that total capital, especially in real estate, in the rich countries can be explained fairly well in terms of the accumulation of flows of saving and investment obviously does not preclude the existence of large local capital gains linked to the concentration of population in particular areas, such as major capitals. It would not make much sense to explain the increase in the value of buildings on the Champs-Elysées or, for that matter, anywhere in Paris exclusively in terms of investment flows. Our estimates suggest, however, that these large capital gains on real estate in certain areas were largely compensated by capital losses in other areas, which became less attractive, such as smaller cities or decaying neighborhoods. (Capital in the Twenty-First Century, p. 197.)

Thomas Piketty’s example of the unearned rise in the value of one’s urban land may seem like an opening for non-distortionary taxation, but in fact from the standpoint of efficiency these positive externalities suggest subsidizing all activities that create these positive externalities for land values, of which just as many are private activities as are activities of the government. (And many activities of the government do not raise land values.) Also, I worry that urban governments often make land prices for certain favored plots go up while reducing the total value of land (and social welfare) by putting tight restrictions on building. This is a concern that Matthew Yglesias raises in his book The Rent Is Too Damn High: What To Do About It, And Why It Matters More Than You Think.

John Stuart Mill on the Tension Between Maintaining the Variation that Ferrets Out Improvements and the Quick Diffusion of Best Practices as Currently Perceived

It is no secret that I am a partisan for Saltwater Macroeconomics as a better route to insight into business cycles than Freshwater Macroeconomics. (For a good sense of my own views, see “On the Great Recession,”“The Neomonetarist Perspective” and “Why I am a Macroeconomist: Increasing Returns and Unemployment.”) Yet, as Noah Smith and I wrote in “The Shakeup at the Minneapolis Fed and the Battle for the Soul of Macroeconomics,”

We are strong proponents of the idea that scientific progress—especially in economics—depends on a vigorous debate among widely divergent points of view.

The analogy that comes to my mind is biological evolution. Genetic variation is the crucial raw material on which natural selection operates in order to raise overall fitness, with all of the fascinating complexity of life that often accompanies higher fitness. Similarly, variation in viewpoints and approaches is the crucial raw material for the advances that result from scientific debate.

One of the key drivers of biological evolution is the need for disease resistance. (Indeed, the Red Queen Hypothesis holds that the key evolutionary driver for the origins of sexual reproduction was the need to outmaneuver parasites.) In agriculture, monocultures that gives a large share of a crop an almost identical genetic makeups run the risk of disastrous blights. In economics, having everyone look at things the same way would risk having no one prepared to understand new circumstances that the world might find itself in. As Noah and I wrote:

Scientifically, Freshwater macroeconomics plays an important role in laying out how the world should be if everyone thought like an economist.

In the future, more people may think much more like economists. And as I point out to my students, when talking about Real Business Cycle models, these models (done as well as possible, of course) establish, the benchmark of what the natural level of output is. And the dynamics of the natural level of output and the natural level of other macroeconomic variables in turn describe how the economy will behave in the future when (I optimistically predict) central banks will be much better at their task of keeping the economy at the natural level of economic activity. We need Freshwater Macroeconomics (again, done as well as possible) to be well-prepared for that possible future. (The blight in the analogy I am pursuing would be a blight on models that focus on the consequences of an output gap in a future when there aren’t much in the way of output gaps any more because monetary policy is so good.)

One of the counterintuitive logical consequences of the importance of diversity of approaches is that diffusing best practices too rapidly can actually be a bad thing. John Stuart Mill explains, in On Liberty, Chapter III: “Of Individuality, as One of the Elements of Well-Being,” paragraph 18 and 19:

The circumstances which surround different classes and individuals, and shape their characters, are daily becoming more assimilated. Formerly, different ranks, different neighbourhoods, different trades and professions, lived in what might be called different worlds; at present, to a great degree in the same. Comparatively speaking, they now read the same things, listen to the same things, see the same things, go to the same places, have their hopes and fears directed to the same objects, have the same rights and liberties, and the same means of asserting them. Great as are the differences of position which remain, they are nothing to those which have ceased. And the assimilation is still proceeding. All the political changes of the age promote it, since they all tend to raise the low and to lower the high. Every extension of education promotes it, because education brings people under common influences, and gives them access to the general stock of facts and sentiments. Improvements in the means of communication promote it, by bringing the inhabitants of distant places into personal contact, and keeping up a rapid flow of changes of residence between one place and another. The increase of commerce and manufactures promotes it, by diffusing more widely the advantages of easy circumstances, and opening all objects of ambition, even the highest, to general competition, whereby the desire of rising becomes no longer the character of a particular class, but of all classes. A more powerful agency than even all these, in bringing about a general similarity among mankind, is the complete establishment, in this and other free countries, of the ascendancy of public opinion in the State. As the various social eminences which enabled persons entrenched on them to disregard the opinion of the multitude, gradually become levelled; as the very idea of resisting the will of the public, when it is positively known that they have a will, disappears more and more from the minds of practical politicians; there ceases to be any social support for nonconformity—any substantive power in society, which, itself opposed to the ascendancy of numbers, is interested in taking under its protection opinions and tendencies at variance with those of the public.

The combination of all these causes forms so great a mass of influences hostile to Individuality, that it is not easy to see how it can stand its ground. It will do so with increasing difficulty, unless the intelligent part of the public can be made to feel its value—to see that it is good there should be differences, even though not for the better, even though, as it may appear to them, some should be for the worse. If the claims of Individuality are ever to be asserted, the time is now, while much is still wanting to complete the enforced assimilation. It is only in the earlier stages that any stand can be successfully made against the encroachment. The demand that all other people shall resemble ourselves, grows by what it feeds on. If resistance waits till life is reduced nearly to one uniform type, all deviations from that type will come to be considered impious, immoral, even monstrous and contrary to nature. Mankind speedily become unable to conceive diversity, when they have been for some time unaccustomed to see it.

However wrongheaded they may seem, minority viewpoints, especially those articulately advanced, are to be treasured as a key to scientific advance and resiliency. Similar things can be said for minority political, cultural, and religious viewpoints. For example, whatever my differences of opinion with the Mormon Church, it is a prodigious generator of important social experiments, many of which may have turned up useful ways of doing things. See for example

- The Message of Mormonism for Atheists Who Want to Stay Atheists

- How Conservative Mormon America Avoided the Fate of Conservative White America

(See also the discussion of non-monetary motivations in Scott Adams’s Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich.) I am confident that those who know them better could point to similar contributions to the rich array of alternatives for ways to organize society that have been identified by other minority religions. (Hint for comments!)

As an example in the cultural vein, while some presume to make strong value judgments about different genre’s of music. I have found many German economists to be scathing in their view of Schlager music, for example, in an intensified version of the way many highly educated Americans look down on Country music as low class. My attitude is that substantial numbers of people enjoy a particular type of music, there is likely to be something to it. I listen trying to find the angle from which I too can get that kind of pleasure from each genre. I may not succeed, and then retain a preference for other music instead, but it is worth giving each genre a good try.

In politics, of course the disdain with which the Left looks upon the Right and the Right looks upon the left has been a target of mine since the beginnings of this blog. I insist that there are crucial insights on both sides of the political spectrum. Our nation and all other democratic nations would go disastrously wrong in their policies if either side of the political spectrum were eradicated from the range of opinions expressed in political action.

One of the most common temptations human beings face is the temptation to try to make people saying something disagreeable shut up. Another common temptation is to try to make people doing something that seems disgusting cease and desist. But stop and consider: a point of view (with its attendant insights) or a way of life (with its attendant practices) that does not currently agree with your own views may someday be your salvation.

Michael Gerson: The Tea Party Will Hurt Republican Prospects Until It Faces Political Reality →

I think Michael Gerson’s analysis is excellent.