What Should the Historical Pattern of Slow Recoveries after Financial Crises Mean for Our Judgment of Barack Obama's Economic Stewardship?

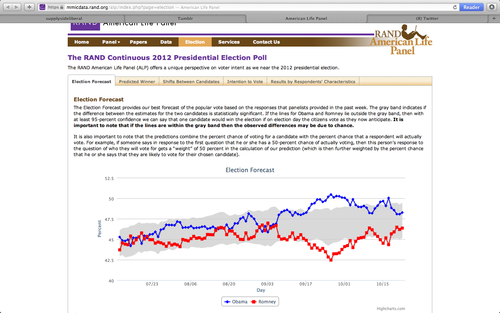

In 2003, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff started writing a book about the aftermath of financial crises: This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Their book’s finding that returning to the previous level of per capita GDP takes a long time after serious financial crises has become part of the political debate. In both the Democratic Convention and in the debates, part of the argument that Barack has done a good job, under the circumstances, has relied on the idea that recoveries should be expected to be especially slow after serious financial crises. Noah Smith ably discusses the merits of the Republican counterattack on the Reinhart-Rogoff finding in his post Reinhart-Rogoff vs. Bordo-Haubrich (with grandstanding by John Taylor). Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff’s own defense of their finding is very useful, especially if you haven’t read their book. They are focused only on the historical evidence in their response. They do not directly engage in the political debate.

I take the Reinhart-Rogoff finding very seriously, and will treat it as a good historical generalization in this post. But I want to point that–even stipulating that returning to the previous level of per capita GDP has historically taken a long time after serious financial crises–the implications of this Reinhart-Rogoff finding for the political debate are much more less clear than the Democratic argument would suggest. In particular, as Carmen and Ken acknowledge in their recent defense of their finding, what happens after a serious financial crisis is not some immutable law of nature, but depends on the policy response. And the key question for the political debate is not if the policy response of the Obama administration’s policy response was better than the policy response to serious financial crises has been historically, but whether the Obama administration’s policy response was as good as it should have been given what was known at the time. The very existence of This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (published in September 2009 and surely existing in draft form quite a bit earlier)within a time period relevant for Obama Administration policy making should set the bar higher.

In particular, in the light of the Reinhart-Rogoff finding that he should have had access to, one can make the argument that Barack should have known he needed to do more than the policies he chose in order to get a robust recovery. Indeed, (as I also cited in my post “Why George Osborne Should Give Everyone in Britain a New Credit Card”) in his excellent Atlantic article, “Obama Explained,” James Fallows wrote:

If keeping the economy growing was so central for Obama, why was the initial stimulus “only” $800 billion? “The case is quite compelling that if more fiscal and monetary expansion had been done at the beginning, things would have been better,” Lawrence Summers told me late last year. “That is my reading of the economic evidence. My understanding of the judgment of political experts is that it wasn’t feasible to do.” Rahm Emanuel told me that within a month of Obama’s election, but still another month before he took office, “the respectable range for how much stimulus you would need jumped from $400 billion to $800 billion.” In retrospect it should have been larger—but, Emanuel says, “in the Congress and the opinion pages, the line between ‘prudent’ and ‘crazy spendthrift’ was $800 billion. A dollar less, and you were a statesman. A dollar more, you were irresponsible.”

Barack certainly had access to Larry Summers’s advice. And I would be surprised if Larry Summers’s advice at the time didn’t incorporate Larry’s awareness of what Carmen and Ken had found. So the fact that Barack did not push for a bigger stimulus package really is an indictment of his economic leadership. According to the reported statement by Larry Summers, it was a political judgement that a bigger stimulus was not politically feasible. I am not at all convinced that a bigger stimulus was politically impossible. It would not have been easy, I’ll grant that, but I was amazed that Barack managed to get Obamacare through. If, instead, Barack had used his political capital and the control the Democrats had over both branches of Congress during his first two years for a bigger stimulus, couldn’t he have done more?

The bottom line is that (asking a lot of Mitt’s protean ability to shapeshift) if Mitt were willing to distance himself far enough from the Republicans in Congress and the Republican orthodoxy, it would be quite possible to use the Reinhart-Rogoff finding to attack Barack’s economic stewardship. Barack should have known the economy needed more stimulus, and in fact his closest economic advisor knew that the economy needed more stimulus! Mitt could then claim that Barack was so set on forcing through health care reform that he took his eye off the more urgent task of ensuring economic recovery. (I remember Peggy Noonan, without specifying what economic policy should have been taken, forcefully making the argument at the time that Barack was putting too high a priority on health care reform relative to fostering economic recovery.) It is a tricky argument for a Republican to make, saying that with the Republicans dead set against both an adequate stimulus and Obamacare, Barack should have focused on the fight for an adequate stimulus rather than for health care reform, but it is a logically cogent one. (I have to confess to my own ignorance about the extent to which Mitt’s own statements about the stimulus package in 2009 would also cause him trouble in making this argument. Given Mitt’s willingness to emphasize at different times a different one of his contradictory statements over others, did he ever say anything then that could be spun as having warned that the stimulus wasn’t big enough–or should have been the same size but focused on things that most economists would agree would have been more effective at raising aggregate demand?)

Aside from the political argument itself, the issues I raise should be part of history’s judgement of Barack Obama. In particular, I take exception to Joe Biden’s claim in the vice presidential debate with Paul Ryan that “no president could have done better” than Barack has done. I suspect, in fact, that Bill Clinton would have done better if he could have been president again. It is quite possible that Hillary Clinton would have done better–in part because she might have been more gun-shy about health care reform and so have focused more intensely on the more immediate economic issue. And Mitt might well have done better had he won the presidency in 2008 (in part because he would have faced less intense Republican opposition to needed stimulus)–though it is hard to know if he would have taken the right policy direction.

Notice that in all of this, I am treating a larger stimulus of a conventional kind as the best among well-discussed policy options when Barack took office in 2009. So I am backing up Paul Krugman’s criticisms of Barack’s policies at the time. However, given what we know now we could do even better, as I discuss in my post “About Paul Krugman: Having the Right Diagnosis Does Not Mean He Has the Right Cure.”

Update:

- Josh Hendrickson sent me a link for a memo from Larry Summers to Barack Obama saying a bigger stimulus was needed, provided by Ryan Lizza,

- as well as to another Ryan Lizza article that discusses Barack Obama more broadly.

- Mark Thoma summarizes Christina Romer’s discussion of what happened with the stimulus here.

- In an earlier version of this post, I said the budget process could get around filibusters. Shai Akabas corrected me: the “budget reconciliation” process that avoids filibusters can only be used when a measure is deficit-reducing.