Matthew Yglesias on Archery and Monetary Policy →

I agree with Matt’s point. We should treat the loss from inflation being too high as no worse than the loss from inflation being too low.

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

I agree with Matt’s point. We should treat the loss from inflation being too high as no worse than the loss from inflation being too low.

Be warned: this Twitter discussion is highly technical.

The Guardian had a feature “Dear George Osborne, it’s time for Plan B say top economists: Seven leading economists on what Chancellor George Osborne should do to revive the ailing UK economy.” That inspired this post with my advice to the United Kingdom on the Independent’s blog, which I reprint here. Thanks to Ben Chu, Jonathan Portes and David Blanchflower for encouragement. (The links below open in the same window, so use the back button to get back.)

Dear Chancellor of the Exchequer,

Since I am an American citizen, it might be argued that I have no business giving advice to the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. But the economic troubles we face are worldwide and I believe are amenable to a common solution if any major nation will show the way with a new tool of macroeconomic stabilization that has fallen into our hands.

The basic problem is that fear is causing many households and firms in the private sector who could spend to cut back on their spending, while others who would be glad to spend more cannot get access to credit. Much of the advice from economists has been for governments to spend more. But even governments that have had good credit ratings and have made some attempt to increase spending have felt limited by the addition to national debt that would result from the amount of extra spending that might be needed to restore economic health. For example, in his excellent Atlantic article, “Obama Explained,” James Fallows wrote:

If keeping the economy growing was so central for Obama, why was the initial stimulus “only” $800 billion? “The case is quite compelling that if more fiscal and monetary expansion had been done at the beginning, things would have been better,” Lawrence Summers told me late last year. “That is my reading of the economic evidence. My understanding of the judgment of political experts is that it wasn’t feasible to do.” Rahm Emanuel told me that within a month of Obama’s election, but still another month before he took office, “the respectable range for how much stimulus you would need jumped from $400 billion to $800 billion.” In retrospect it should have been larger—but, Emanuel says, “in the Congress and the opinion pages, the line between ‘prudent’ and ‘crazy spendthrift’ was $800 billion. A dollar less, and you were a statesman. A dollar more, you were irresponsible.”

What is needed—mainly for genuine economic reasons, but also for political reasons—is a way to provide a large amount of stimulus without adding too much to the national debt. In my new academic paper “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy,” and on my blog, I propose and discuss a tool for macroeconomic stabilization that can do exactly that. The proposal, which I call “National Lines of Credit,” (or “Federal Lines of Credit” in the US case) is to send government-issued credit cards to all taxpayers that have a substantial line of credit attached—say £2,000 per adult, or £4,000 pounds per couple. The interest rate would be relatively favorable, say 6%, with a 10-year repayment period so that most of the repayment would happen after the economy is back on its feet again. But the government would insist on eventual repayment, except for the very-long-term unemployed or disabled. Insisting on repayment would make the ultimate addition to the national debt small compared to the stimulus provided by these National Lines of Credit.

The paper provides many more details of how National Lines of Credit might work than I should try to include here, but I should mention that a key detail is requiring each household not only to pay down its debt, but also to build up a reserve of savings after the economy has fully recovered. That reserve of savings would be there to help deal with any more distant future crisis. Also, let me say that, depending on the exactly how they are implemented, National Lines of Credit are either distributionally neutral or tend to favor the poor; by contrast, the Bank of England has estimated that its program of buying gilts (which might also be necessary) has had immediate benefits tilted toward the wealthy.

Perhaps just as important as the stimulus provided by a program of National Lines of Credit would be the value of demonstrating that this kind of approach works, if it does, or gaining a greater understanding of the workings of the economy if it doesn’t. The best existing evidence- historical evidence based on the decision to allow World War 1 veterans in the U.S. to borrow against their veterans’ bonuses – suggests that the stimulus effect can be substantial. But the politics of many nations will require more evidence before National Lines of Credit can be implemented there. (Many nations in the Eurozone need a program of National Lines of Credit even more than the United Kingdom does.) Some nation must blaze the trail. If the United Kingdom is willing to take the risk of going first in trying out this new stimulus measure, and it works, it will not only have helped to solve its own economic troubles, it will have earned the gratitude of the world, in a small but still significant echo of the way in which it earned the gratitude of the world by standing against Hitler.

Miles Kimball is an economics professor at the University of Michigan who studies business cycles and the effects of risk on household consumption. He blogs about economics and politics at supplysideliberal.com.

Update:

19. Why George Osborne Should Give Everyone in Britain a New Credit Card

20. Twitter Round Table on Federal Lines of Credit and Monetary Policy

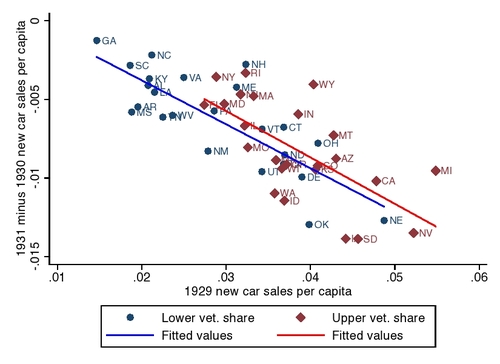

Guest blogger Joshua Hausman’s graph of the change in car sales in each state between 1930 and 1931, as a function of car sales in 1929, broken into those states with below-median fraction of veterans in the population (blue) and above-median fraction of veterans in the population (red). The fitted lines do not impose equal slopes.

The graph excludes the District of Columbia (DC), since it is a large outlier. Including DC strengthens the case for an effect of being allowed to borrow against the veteran’s bonus on auto sales: DC had a high share of veterans and was the only state to see auto sales actually increase from 1930 to 1931.

This is a guest post by Joshua Hausman. Joshua is a graduate student at Berkeley on the job market this Fall.

Perhaps the best historical analogies to Miles’s Federal Lines of Credit Proposal are 1931 and 1936 policy changes that gave World War I veterans early access to a promised 1945 bonus payment. In 1924, Congress passed a bill promising veterans large payments in 1945. When the depression came, veterans’ groups lobbied congress for immediate payment. Congress partially acquiesced in 1931, giving veterans the ability to borrow up to 50 percent of the value of their promised bonus beginning on February 27. (Prior to this, veterans could take loans of roughly 22.5 percent of their bonus.) For the typical veteran, this meant being able to borrow about $500. For comparison, in 1931 per capita personal income was $517. The loans carried an interest rate of 4.5 percent, but interest did not have to be paid annually. Rather, the amount of the loan plus interest would be deducted from what was due the veteran in 1945. In fact, the interest rate was lowered to 3.5 percent in 1932, and then forgiven entirely in 1936. But there is no reason to think that this was expected at the time.

Despite their ability to take loans, veterans continued to demand immediate cash payment of the entire, non-discounted, value of their bonus. Tens of thousands of veterans camped in Washington, DC from May to July 1932 to lobby for immediate payment. Finally, in 1936, congress granted their wish, giving veterans the choice of taking their bonus in cash or leaving it with the government where it would earn 3 percent interest until 1945. Whereas the 1931 policy change was a pure loan program, the 1936 policy had elements of both a loan and a transfer, since it gave veterans access to the same amount of cash in 1936 that they otherwise would have gotten in 1945, and since part of the 1936 bill forgave interest on earlier loans. A rough calculation suggests that of the typical bonus amount of $550 received in 1936, roughly half was an increase in veterans’ permanent income, while the other half was essentially a loan.

My ongoing work focuses on evaluating the 1936 bonus, both because it was quantitatively much larger than the 1931 loan payments, and because there is a household consumption survey and a survey of veterans themselves that makes it possible to evaluate the policy’s effects in detail. But the 1931 program is a better analogy for Miles’ Federal Line of Credit proposal. Thus in the rest of this blog post I consider what evidence there is on the 1931 program.

No single source of evidence is definitive, but several pieces of evidence suggest that loans to veterans boosted consumption in 1931. First, it is significant that veterans eagerly took advantage of the loan program. In the four months following the policy change (March to June 1931), veterans took 2.06 million loans worth an aggregate $796 million, or one percent of GDP. Since there were 3.7 million World War I veterans, these figures suggest that a majority quickly took advantage of the loan program (that is, unless many veterans took multiple loans). Given the 4.5 percent interest rate, and the lack of many attractive investment opportunities in the 1931 economy, it only made sense for veterans to take these loans to consume or to pay down high interest rate debt.

Other evidence points to veterans using some of the money on consumption rather than using it entirely to pay down debt. First, there is an uptick in department store sales amidst what is otherwise a steady downward trend. Seasonally adjusted sales rose 2.9 percent in April, the month when veterans took out the most loans. Since the proportion of veterans in the population varied significantly across states, it is also possible to relate changes in new car sales in a state to the number of veterans in the state, and thus measure the effect of the loan program. Uncovering whether or not there was such a relationship is tricky since the loan program was small compared to the other shocks hitting the economy. In particular, states with more veterans tended to be states in the west, and these states had higher car sales in 1929. In turn, states that had higher car sales in 1929 tended to see larger declines in sales during the Depression. A way to see both the relationship to 1929 sales, and the effect of veteran share is to graph the 1930-31 change in car sales per capita against the level of 1929 car sales. This is done in the figure at the top. The blue dots are states in the lower half of the veteran share distribution (i.e. states with fewer than 2.9 veterans per 100 people) and the red dots are states in the top half of the veteran share distribution. The lines are the fitted values for each set of points. The graphical evidence is hardly definitive, but it is at least consistent with the fact that conditional on pre-depression conditions, being in the top half of the veteran share distribution led to higher auto sales in 1931.

Finally, narrative sources provide some indication of what people at the time thought veterans were doing with the money. News stories are also consistent with veterans spending the money on cars. For example, the Los Angeles Times wrote on March 22, 1931: “The opinion has been ventured that the bonus readjustment would have a beneficial effect upon the motor trade and that a liberal amount of this money would find its way into the pockets of the automobile dealer. The prediction is becoming a fact to a greater extent than was at first anticipated."

Newspapers also reported veterans spending on other consumer items. The New York Times wrote on April 5, 1931: "That the payment of the soldiers’ bonus has definitely increase purchases of merchandise, particularly men’s wear, was the opinion yesterday of Julian Goldman, head of the Julian Goldman Stores, Inc., which sell goods on the instalment [sic] plan. Mr. Goldman recently returned from an extended trip through the country and reported that managers of his own stores and other merchants attributed a substantial increase in sales to the veterans spending their loan money.” The article goes on to also say that veterans were using their loans to pay back installment debt on previous clothing purchases.

2012 is not 1931 and a trial of Federal Lines of Credit today would provide much better evidence of its effects. But the 1931 experience is at least encouraging. The balance of evidence suggests that the loan program was popular and that it increased consumption relative to what it otherwise would have been. Of course, the economy still saw large absolute declines in consumption and output in 1931, since the loan program was tiny compared to the negative shocks hitting the economy.

Information on the the bonus legislation and the number and dollar amount of loans is taken from the 1931 Annual Report of the Administrator of Veterans’ Affairs, in particular, p. 42; data on seasonally adjusted department store sales are from

http://www.nber.org/databases/macrohistory/rectdata/06/m06002a.dat.

Data on veterans per capita in each state are from the 5% IPUMS sample from the 1930 Census; data on new car sales by state are from the industry trade publication Automotive Industries, data for 1929 sales is from the February 22, 1930 issue, p. 267, for 1930 from the February 28, 1931 issue p. 309, and for 1931 from the February 27, 1932 issue p. 294.

A Principles of Macroeconomics Post

This is a great 6-minute video giving a sense of what the “Occupy Wall Street” movement and its spinoffs are all about.

For the other side, I would love to identify a video this good that is sympathetic to the “Tea Party” movement. Also, there must be good short videos about the financial crisis and the Great Recession themselves–the financial crisis and Great Recession that were the impetus for both the “Occupy Wall Street” and “Tea Party” movements.

Mary O'Keeffe taught my section of Ec 10 (Harvard’s full-year introduction to economics) back in the 1977-1978 school year. (Ec 10 is taught almost entirely in section, with the big lectures only icing on the cake, so she was my main instructor.) She gave me permission to reprint these thoughts that she posted on her Facebook page:

I don’t agree with everything the brilliantly eclectic Miles Kimball writes, but this piece [“Scott Adams’s Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich”] resonates very deeply with my soul. (For those who don’t remember my earlier reference, Miles was a student in the very first intro econ class I taught at Harvard as graduate teaching fellow in the late 70s.)

He is far more nuanced and thoughtful than I would have guessed from those days–but I suppose that I too have grown more nuanced and thoughtful. I think both of us realize that there is good and bad in everything and everyone, and try to find ways to elicit the good in ourselves and others.

(Miles, who was raised a Mormon and is now a UU [Unitarian-Universalist] with a deep reverence for the good parts of his upbringing, thinks there are both good and [bad] things about his cousin Mitt Romney as well as good and bad things about President Obama. I think the same is true of everyone–some good things and some bad things–we are all flawed human beings operating in a highly imperfect world, and though I think I come down far more clearly on the side of President Obama than on the side of Mitt Romney, I think there is value in trying to understand everyone’s ideas and point of view and trying to find the best of what is within each of us.)

In short, I like this essay [“Scott Adams’s Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich”] very much.

I am especially pleased that Mary likes my post “Scott Adams’s Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich” yesterday since that matches my own judgment about the importance of that post compared to most of my other posts. I tweeted that it was “My most important post in a long time”–though since my blog has been in existence less than three months, “most important post in a long time” here means “best of the 62 posts after both ’You Didn’t Build That: America Edition‘ on July 24th and ’Teleotheism and the Purpose of Life' on July 25th.”

Mary wrote this addendum to her review:

Your post [“Scott Adams’s Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich”]–by the way–reminded me of the sense of pride I feel in being part of a community of taxpayers that collectively finance public goods that exhilarate me and that I can share with the community at large.

The sudden joy of the realization one day that everyone in our community could have access to the breathtaking views from Thatcher State Park overlooking the Capital District and the bike-hike path running along the Mohawk River and the stunningly gorgeous roses in Schenectady’s Central Park Rose Garden and our great public libraries and nonprofit volunteer theater groups’ free performances in the public parks and the community spirit of all the varied denominations of churches that work together in service projects filled me with such exhilaration that I wrote this post on my own blog:

http://bedbuffalos.blogspot.com/2010/09/why-i-teach-public-finance.html

Scott Adams with his creation “Dilbert"

With all the pleasure he has given millions with his Dilbert comics and all of his other incisive Wall Street Journal essays, it is a high standard indeed to say that one particular Wall Street Journal essay is Scott Adam’s finest hour, but I think this is it: “How to Tax the Rich.” Let me know in the comments what other wonderful things there are out there by Scott that can vie for the honor of Scott’s finest hour.

Even after allowing for comic license, I think I can say that Scott himself is conscious of the value of his own idea, as can be seen from these two passages:

Whenever I feel as if I’m on a path toward certain doom, which happens every time I pay attention to the news, I like to imagine that some lonely genius will come up with a clever solution to save the world. Imagination is a wonderful thing. I don’t have much control over the big realities, such as the economy, but I’m an expert at programming my own delusions.

Try to imagine that the idea that saves the country is an entirely new one. It’s too much of a stretch to imagine that a stale idea would suddenly become acceptable. In fact, that’s the dividing line between imagination and insanity. Only crazy people imagine that bad ideas can suddenly become good if you keep trying them. So let’s assume that our imagined solution is a brand new idea. That feels less crazy and more optimistic. Another advantage is that no one has an entrenched view about an idea that has never been heard.

For those of you with healthy egos—and that would be every reader of The Wall Street Journal—you can make this fantasy extra delicious by imagining that you are the person who comes up with the idea that saves the world. I’ll show you how to imagine that.

Scott’s overall idea is based on a fundamental fact that Giorgio Primiceri pointed out when I talked to him about taxing the rich at CREI in Barcelona in June: because each dollar is worth less and less the richer one is, a wide variety of other things end up mattering more for rich people than money. (On the principle that each dollar is worth less for the rich than for the poor in interpersonal comparisons, see my post “What is a Supply-Side Liberal?” But the point here is different: here it is about the value of a dollar compared to other things the rich person wants.) One should be careful: sometimes, one of the things that propels someone toward riches is having a greater desire for the things that money can buy than the average person (relative to, say, a desire for leisure time). But still, at some level of riches, the attractions of the things that extra money could directly purchase start to pale in comparison to other things, even for someone who truly loves the things that money can buy.

Scott writes:

If we accept that the rich can be taxed at a different rate than everyone else, we can also imagine that there could be other differences in how the rich are taxed. That’s the part we can tinker with, and that’s where the bad version comes in. In a minute, I’ll float some bad ideas about how the rich can feel good while the rest of society is rifling through their pockets.

I can think of five benefits that the country could offer to the rich in return for higher taxes: time, gratitude, incentives, shared pain and power.

The trouble with our tax system as it stands–and this has nothing to do with its arithmetic–is that instead our tax system does just about everything possible to make paying taxes a horrible, aversive, demeaning experience for the rich, even apart from the money they surrender.

Although few of us make it into the top 1%, my fellow economists and I definitely count among the moderately rich. Certainly folks as rich as we economists are–or as many other highly-paid professionals such as doctors and lawyers are–need to be taxed relatively heavily in order to get enough revenue to fund the government at anything close to its current level. And we are. With the voice of my late colleague Tom Juster in my head reminding me of the joys of helping the poor through paying my taxes, I don’t personally need one, but I find it remarkable that I have yet to receive a thank you note for paying my taxes. When I fill out my taxes, I notice that even receipts for $25 donations have thank you notes attached. But for the tens of thousands of dollars I give each year to help keep our wonderful Republic afloat, nothing. Can’t we do a little more as a nation to honor our taxpayers individually? If the First Spouse is willing, how about a thank-you note for every taxpayer signed by the President of the United States and the often much-more-popular First Spouse? (To save on postage, it could be mailed along with the annual Social Security report people get sometime close to their birthdays, for example.) And how about a dinner at the White House honoring the top 100 taxpayers in the country? Not the 100 richest people in the country, but the top 100 taxpayers. One might object that they would just use the opportunity to lobby for lower taxes, but if they did, they wouldn’t get invited the next year. If we honored the top 100 taxpayers like that, maybe they wouldn’t feel like fools for paying their taxes instead of finding some way to evade them like many of their friends and acquaintances.

A thank you note for every taxpayer and a dinner at the White House honoring the top 100 taxpayers are just two of many possible specific ideas for enlisting the full range of people’s motivations in an effort to make paying taxes something that people won’t try quite as hard to avoid. I promise to work hard to come up with more ideas in future posts, and encourage other bloggers to do the same. In trying to come up with ideas along these lines, I rest easy in the confidence that Scott is covering my flank with much wilder proposals. He explains his approach as follows, picking up after a passage I quoted earlier:

For those of you with healthy egos—and that would be every reader of The Wall Street Journal—you can make this fantasy extra delicious by imagining that you are the person who comes up with the idea that saves the world. I’ll show you how to imagine that.

I think you’ll be surprised at how easy it is. I spent some time working in the television industry, and I learned a technique that writers use. It’s called “the bad version.” When you feel that a plot solution exists, but you can’t yet imagine it, you describe instead a bad version that has no purpose other than stimulating the other writers to imagine a better version.

I’ll leave you to read for yourself the specific ideas Scott proposes in “How to Tax the Rich.” They are sure to inspire each of you with the thought “I can do better than that.”

Standard economic models of taxation (such as the one in my post “The Flat Tax, the Head Tax, and the Size of Government: A Tax Parable”) simplify by focusing only on a small list of desires (say consumption purchased in the market, leisure and public goods). But human beings want many things, including many intangibles. It is my belief that we can do much better at harnessing these other desires for the common good than we have. Once upon a time, many Communists made the mistake of thinking that even for the typical individual other motivations could be made to supersede the desires for the things money can buy. Unfortunately, the only desire they found that was reliably stronger was the desire to avoid being shot, sent to Siberia, or the like. But surely we can construct a better society if we recognize the other desires people have at the strength those desires actually have.

Let me end by giving two routine examples of how much people will do for motivations other than money. First, I once received an email from a professor I had known at Harvard, asking why Kim Clark would step down from his position as Dean of Harvard Business School to take a position as President of Brigham Young University-Idaho (the Mormon Church’s second most important university, coming after the better-known Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah). The question arose because in the normal pecking order of academic leadership positions, President of BYU-Idaho is a big step down from Dean of Harvard Business School, and the move probably reduced Kim Clark’s lifetime earning power significantly. My answer was fairly simple: religious motivations that motivated Kim Clark as a believing Mormon.

Second, although I have already cited it in my post “Copyright,” I love Eli Dourado’s post “Why I Should Blog More” so much, I am going to quote from it here as well. Eli writes:

People still think that the public goods problem is a problem. The naïve view of public goods is often at odds with reality, however. This is especially so when one considers the things we might care most about: our jobs and relationships. In modern society, better jobs and relationships are often the reward for the production of positive externalities. As it turns out, people like to work and socialize with those who create value for others.

This effect is pretty strong. Can you name a person who ended up poor and unhappy because they devoted too many resources to the voluntary production of public goods of actual value to the rest of society? I can’t, at least not off the top of my head.

My standard advice for those few younger people who ask me for it is simply to produce a lot of external value. Don’t worry about being compensated for it right away. If you succeed in producing things that are of value to others, they will want you around, and you will have plenty of rewarding opportunities you would not have had otherwise.

If we could arrange things so that paying taxes to indirectly support public goods could somehow result in the kinds of delayed benefits Eli traces as resulting from directly producing public goods, we wouldn’t have to worry so much about tax distortions.

The marginal cost of producing and storing an extra electronic copy of a book is almost zero. But the fixed cost is the cost of the writer’s time. Our mixed emotions about the ethics of copyright and violating copyright come from the tension between our feeling that things should have something close to marginal cost pricing and our feeling that authors and other creators should be compensated. Tim Parks captures these mixed emotions brilliantly in this New York Review of Books essay.

Cases such as electronic copies of books, where the marginal cost is essentially zero, provide great examples of how increasing returns to scale is incompatible with perfect competition. As long as the cost of writing a book is positive–

“No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money,” Samuel Johnson once remarked [quoted in Tim’s essay]

–there will be increasing returns to scale for electronic copies of the book. By reducing the price of an electronic copy of a book to zero, perfect competition would lead to very little writing of books where the cost of writing a book is positive. Hence, copyright law.

But where the cost of creation–net of benefits to the creator other than selling the zero-marginal-cost copies–is zero or negative, copyright law might not be necessary. Tim:

If people only read poetry, which you can never stop poets producing even when you pay them nothing at all, then the law of copyright would disappear in a trice.

Eli Dourado, in “Why I Should Blog More,” argues persuasively that many forms of individual creation are in this category: things people would do for the many informal social benefits that flow to those who do something useful for society, even without any direct payment.

In reality, there are a wide variety of different forms of creative output that each have a different lineup of likely rewards for creators. (For example, Tim has a good discussion of the complex set of benefits one might get from writing a song.) With different forms of creative output that have different lineups of likely rewards often treated similarly in copyright law, it is not clear that we have struck the right balance.

Update: Let me give you a few interesting links that also question whether we have struck the right balance in copyright law:

Rahm Emanuel (as can be seen in this 13-second video) famously said

You never want a serious crisis to go to waste. And what I mean by that is it’s an opportunity to do things you could not do before.

Here, Matt Yglesias reviews a new book by Michael Grunwald documenting the ways in which the Obama administration used the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (the “Stimulus Bill”) to accomplish many of its other legislative priorities in addition to trying to stimulate the economy. Though many of those other legislative priorities were arguably in the right direction, I think the commingling of stimulus with other efforts having a more partisan coloring accounts for some of the Republican hatred of the Stimulus Bill. This is a good example of the political economy issues I discuss in my post “Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football.”

I wanted to link to Josh Barro’s piece because it illustrates how the tradeoff between government support for the poor and government support for the old is showing up in the current political campaign.

The political triumph of the old over the poor is an instance of “Director’s Law.” In my post “Milton Friedman: Celebrating His 100th Birthday With Videos of Milton” I quote Milton’s definition of Aaron Director’s Law:

Director’s Law is, that almost invariably, government programs benefit the middle income class, at the expense of the very poor and the very rich.

In my post “You Didn’t Build That: America Edition” I wrote:

We didn’t build this unbelievable American system, and it is not our private property. We don’t have a moral right to exclude other human beings—human beings like us—from the benefits of this unbelievable American system. As stewards of this unbelievable American system, we need to regulate the pace of arrival so that the system itself is not overwhelmed and destroyed, but unless this unbelievable American system itself is threatened, let us open our doors wide to others who have not had the good fortune to be born Americans.

(“This unbelievable American system” is Barack’s phrase.) Vipul Naik and Garett Jones argue, as I would argue as well, that it is not that easy to overwhelm “this unbelievable American system” with new arrivals.

In my post “Health Economics” I propose (in effect, if not in so many words) that in place of the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) states be allowed to experiment with different ways to provide universal access to medical care. On Twitter (as storified in “Miles Kimball and Noah Smith on Balancing the Budget in the Long Run”), I have sharpened that proposal to what can be translated out of Twitter shorthand to this:

Let’s abolish the tax exemption for employer-provided health insurance, with all of the money that would have been spent on this tax exemption going instead to block grants for each state to use for its own plan to provide universal access to medical care for its residents.

Evan Soltas argues here that a somewhat decentralized approach in this spirit has worked well in Canada, for at least a part of its medical spending.

A Principles of Macroeconomics Post

This is a crystal clear description of how hard it is to avoid the need for substantial government revenue increases in the future–even as a percentage of GDP. The reality Larry Summers describes is why I am so focused on the dilemma I talk about in my first post, “What is a Supply-Side Liberal?”

This is a good introduction to the political debate about the role of economic uncertainty in our current economic troubles, plus a good discussion of Keynes’s views about uncertainty.

A Principles of Macroeconomics Post

This 7-minute interview with Paul Fletcher (senior partner at Actis) gives a nice sense of what investment in emerging markets looks like. There is also a side discussion of leveraged buyouts such as those Mitt was engaged in.

This is long–2 hours and 22 minutes–so you should only try to listen to this if you are a bear for punishment. But I thought some of you might be interested.

Jane Austen’s book Persuasion–unrelated to the post, but a good book

I had a wide-ranging question and answer session with the Ann Arbor Science and Skeptics group yesterday about this blog. The one theme I emphasized throughout the Q&A was how good it feels to be unabashedly normative in the sense of making recommendations and making moral arguments as well as technical arguments. Even the concept of a moral argument is interesting. How can one get beyond solipsistic relativism such as the following?

You have your opinions and I have mine, and all opinions are equally worthy, so we can’t really have a discussion.

Coming to that question as a math guy, I have always thought that persuasion needs to start with the axioms of the person I am trying to persuade. As a blogger, I have to guess the axioms–core beliefs that are fundamental in the sense that they cannot be deduced from other beliefs–of a large number of people all at once. And to the extent that people come from different places, I have to write posts that alternately work from the axioms of different parts of my audience. In order to do my job as a blogger better, I would love to hear about your axioms in the comments.

Postscript: In the Q&A session at Ann Arbor Science and Skeptics, I realized that there are two areas of nonpartisan activism I would like to recommend:

Postpostscript: I wanted to thank the large number of people who sent birthday congratulations for me. I tried not to tell anyone online my birthday, but Facebook did it for me. I turned 52 on August 17. It is amazing to think there are as many years behind me as there are weeks in a year. I really appreciate hearing so many kind wishes and kind words from you all.

Update, 2013: On August 17, 2013, I turned 53. I was born in 1960. 1960 was a high birth-rate year, but it was one of the last high-birth-rate years in the baby boom. I have always felt younger than the baby boomers described in popular culture.