Michael Pollan on the Costs as Well as Benefits of Caffeine →

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The University of Colorado Boulder Deals with a Free Speech Issue

I found this in my email inbox this morning, which I thought might be of interest to many of you. I am proud to part of a university that defends free speech—even when that speech is understandably objectionable to many.

Dear CU Boulder faculty,

Professor John Eastman, one of our visiting scholars in conservative thought and policy, recently published an op-ed that questioned whether Senator Kamala Harris is eligible to serve as vice president, even though she was born in the United States. This op-ed has both served as a lightning rod nationally for those who wish to delegitimize Senator Harris’s candidacy and has inflamed tensions on a campus that is confronting how it must acknowledge and overcome racism. Many scholars in our community and beyond have criticized the op-ed’s substance as promoting a rejected constitutional theory, and many within our community have reached out to me to express their outrage that a member of our community’s scholarship is being used by others across the country to promote a racist agenda.

I read Professor Eastman’s op-ed, and I found it neither compelling nor consistent with my understanding of who is eligible to hold our highest elected offices. I also condemn the way his work has been used to promote a racist agenda against the historic candidacy of Senator Harris, the daughter of a Jamaican-born father and an Indian-born mother. Never before has a woman of color been a candidate for the vice presidency. Even if he did not intend it, Professor Eastman’s op-ed has marginalized members of our CU Boulder community and sown doubts in our commitment to anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion. I am grateful to all who have expressed concerns that his work runs counter to our values as a campus. It undoubtedly damages our efforts to build trust with our communities of color at a critical time when we are working to build a more inclusive campus culture.

Without minimizing those harms, and recognizing that we must repair that trust, I must speak to those who have asked whether I will rescind Professor Eastman’s appointment or silence him. I will not, for doing so would falsely feed a narrative that our university suppresses speech it does not like and would undermine the principles of freedom of expression and academic freedom that make it possible for us to fulfill our mission.

Academic freedom includes the rights and responsibilities afforded to faculty members to create and disseminate knowledge and seek truth as the individual understands it, subject to the standards of their disciplines and the rational methods by which truth is established. Even legal scholars who reject Professor Eastman’s constitutional arguments recognize his theories are debatable.

If I would deny Professor Eastman these rights, it would weaken our ability to defend our entire faculty’s pursuit and dissemination of scholarship without fear of censorship or retaliation, even when it offends the sensibilities of others and makes people uncomfortable. However, I do encourage all of us—our visiting scholars included—to remember that while we as faculty have the privilege of academic freedom, that privilege comes with significant collective and individual responsibilities.

As stated in the American Association of University Professors 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, “College and university teachers are citizens, members of a learned profession, and officers of an educational institution. When they speak or write as citizens, they should be free from institutional censorship or discipline, but their special position in the community imposes special obligations. As scholars and educational officers, they should remember that the public may judge their profession and their institution by their utterances. Hence, they should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, should show respect for the opinions of others, and should make every effort to indicate that they are not speaking for the institution.”

People can, and do, judge our institution by what we say. We must never forget that what we do and say as scholars has real impact, and that upholding the principles that enable our mission and support our democracy is more important now than ever—particularly as we seek to build a more inclusive climate within our campus and our country.

Last year, the Office of Faculty Affairs initiated a campus-wide discussion to enable a clearer understanding of academic freedom and its vital importance on our campus. In that spirit, Provost Moore and I, in coordination with the Office of Faculty Affairs, will host panel discussions this fall and spring that will include a range of representatives and perspectives. Our discussions will include a panel on how scholarship can impact our community’s Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC), can be weaponized and has the potential to marginalize.

I hope you will join us in these important and necessary conversations, and I am grateful for your tireless work and commitment to our mission during this difficult time.

Best regards,

Philip P. DiStefano

Chancellor

In case you thought I was still at the University of Michigan, take a look at

and my blog bio.

The Federalist Papers #15: A Government, to be Worthy of the Name, Must Govern Its Citizens, Not Just Its Subordinate Jurisdictions—Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton’s point in the Federalist Papers #15 is to argue that the Articles of Confederation—which were the status quo relative to adopting the Constitution—were too weak. He has three basic arguments:

Almost everyone agrees the Articles of Confederation are too weak—or they did agree the Articles of Confederation were too weak until they saw the nature of the fix that is proposed.

Experience has shown that the Articles of Confederation are too weak.

Given the structure established by the Articles of Confederation, they were bound to be too weak: in particular, having the federal government govern states as opposed to governing citizens is a fatal flaw, disastrously weakening the federal government.

Let me take Alexander Hamilton’s words and add bold italics, and in some places add bullets to emphasize the passages I think are most central to his argument. (For convenience, I also brought a footnote up to the main text, but in square brackets.)

FEDERALIST NO. 15

The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union

For the Independent Journal.

Author: Alexander Hamilton

To the People of the State of New York:

IN THE course of the preceding papers, I have endeavored, my fellow-citizens, to place before you, in a clear and convincing light, the importance of Union to your political safety and happiness. I have unfolded to you a complication of dangers to which you would be exposed, should you permit that sacred knot which binds the people of America together be severed or dissolved by ambition or by avarice, by jealousy or by misrepresentation. In the sequel of the inquiry through which I propose to accompany you, the truths intended to be inculcated will receive further confirmation from facts and arguments hitherto unnoticed. If the road over which you will still have to pass should in some places appear to you tedious or irksome, you will recollect that you are in quest of information on a subject the most momentous which can engage the attention of a free people, that the field through which you have to travel is in itself spacious, and that the difficulties of the journey have been unnecessarily increased by the mazes with which sophistry has beset the way. It will be my aim to remove the obstacles from your progress in as compendious a manner as it can be done, without sacrificing utility to despatch.

In pursuance of the plan which I have laid down for the discussion of the subject, the point next in order to be examined is the "insufficiency of the present Confederation to the preservation of the Union." It may perhaps be asked what need there is of reasoning or proof to illustrate a position which is not either controverted or doubted, to which the understandings and feelings of all classes of men assent, and which in substance is admitted by the opponents as well as by the friends of the new Constitution. It must in truth be acknowledged that, however these may differ in other respects, they in general appear to harmonize in this sentiment, at least, that there are material imperfections in our national system, and that something is necessary to be done to rescue us from impending anarchy. The facts that support this opinion are no longer objects of speculation. They have forced themselves upon the sensibility of the people at large, and have at length extorted from those, whose mistaken policy has had the principal share in precipitating the extremity at which we are arrived, a reluctant confession of the reality of those defects in the scheme of our federal government, which have been long pointed out and regretted by the intelligent friends of the Union.

We may indeed with propriety be said to have reached almost the last stage of national humiliation. There is scarcely anything that can wound the pride or degrade the character of an independent nation which we do not experience.

Are there engagements to the performance of which we are held by every tie respectable among men? These are the subjects of constant and unblushing violation.

Do we owe debts to foreigners and to our own citizens contracted in a time of imminent peril for the preservation of our political existence? These remain without any proper or satisfactory provision for their discharge.

Have we valuable territories and important posts in the possession of a foreign power which, by express stipulations, ought long since to have been surrendered? These are still retained, to the prejudice of our interests, not less than of our rights.

Are we in a condition to resent or to repel the aggression? We have neither troops, nor treasury, nor government.["I mean for the Union."]

Are we even in a condition to remonstrate with dignity? The just imputations on our own faith, in respect to the same treaty, ought first to be removed.

Are we entitled by nature and compact to a free participation in the navigation of the Mississippi? Spain excludes us from it.

Is public credit an indispensable resource in time of public danger? We seem to have abandoned its cause as desperate and irretrievable. Is commerce of importance to national wealth? Ours is at the lowest point of declension. Is respectability in the eyes of foreign powers a safeguard against foreign encroachments? The imbecility of our government even forbids them to treat with us. Our ambassadors abroad are the mere pageants of mimic sovereignty. Is a violent and unnatural decrease in the value of land a symptom of national distress?

The price of improved land in most parts of the country is much lower than can be accounted for by the quantity of waste land at market, and can only be fully explained by that want of private and public confidence, which are so alarmingly prevalent among all ranks, and which have a direct tendency to depreciate property of every kind. Is private credit the friend and patron of industry?

That most useful kind which relates to borrowing and lending is reduced within the narrowest limits, and this still more from an opinion of insecurity than from the scarcity of money. To shorten an enumeration of particulars which can afford neither pleasure nor instruction, it may in general be demanded, what indication is there of national disorder, poverty, and insignificance that could befall a community so peculiarly blessed with natural advantages as we are, which does not form a part of the dark catalogue of our public misfortunes?

This is the melancholy situation to which we have been brought by those very maxims and councils which would now deter us from adopting the proposed Constitution; and which, not content with having conducted us to the brink of a precipice, seem resolved to plunge us into the abyss that awaits us below. Here, my countrymen, impelled by every motive that ought to influence an enlightened people, let us make a firm stand for our safety, our tranquillity, our dignity, our reputation. Let us at last break the fatal charm which has too long seduced us from the paths of felicity and prosperity.

It is true, as has been before observed that facts, too stubborn to be resisted, have produced a species of general assent to the abstract proposition that there exist material defects in our national system; but the usefulness of the concession, on the part of the old adversaries of federal measures, is destroyed by a strenuous opposition to a remedy, upon the only principles that can give it a chance of success. While they admit that the government of the United States is destitute of energy, they contend against conferring upon it those powers which are requisite to supply that energy. They seem still to aim at things repugnant and irreconcilable; at an augmentation of federal authority, without a diminution of State authority; at sovereignty in the Union, and complete independence in the members. They still, in fine, seem to cherish with blind devotion the political monster of an imperium in imperio. This renders a full display of the principal defects of the Confederation necessary, in order to show that the evils we experience do not proceed from minute or partial imperfections, but from fundamental errors in the structure of the building, which cannot be amended otherwise than by an alteration in the first principles and main pillars of the fabric.

The great and radical vice in the construction of the existing Confederation is in the principle of LEGISLATION for STATES or GOVERNMENTS, in their CORPORATE or COLLECTIVE CAPACITIES, and as contradistinguished from the INDIVIDUALS of which they consist. Though this principle does not run through all the powers delegated to the Union, yet it pervades and governs those on which the efficacy of the rest depends. Except as to the rule of appointment, the United States has an indefinite discretion to make requisitions for men and money; but they have no authority to raise either, by regulations extending to the individual citizens of America. The consequence of this is, that though in theory their resolutions concerning those objects are laws, constitutionally binding on the members of the Union, yet in practice they are mere recommendations which the States observe or disregard at their option.

It is a singular instance of the capriciousness of the human mind, that after all the admonitions we have had from experience on this head, there should still be found men who object to the new Constitution, for deviating from a principle which has been found the bane of the old, and which is in itself evidently incompatible with the idea of GOVERNMENT; a principle, in short, which, if it is to be executed at all, must substitute the violent and sanguinary agency of the sword to the mild influence of the magistracy.

There is nothing absurd or impracticable in the idea of a league or alliance between independent nations for certain defined purposes precisely stated in a treaty regulating all the details of time, place, circumstance, and quantity; leaving nothing to future discretion; and depending for its execution on the good faith of the parties. Compacts of this kind exist among all civilized nations, subject to the usual vicissitudes of peace and war, of observance and non-observance, as the interests or passions of the contracting powers dictate. In the early part of the present century there was an epidemical rage in Europe for this species of compacts, from which the politicians of the times fondly hoped for benefits which were never realized. With a view to establishing the equilibrium of power and the peace of that part of the world, all the resources of negotiation were exhausted, and triple and quadruple alliances were formed; but they were scarcely formed before they were broken, giving an instructive but afflicting lesson to mankind, how little dependence is to be placed on treaties which have no other sanction than the obligations of good faith, and which oppose general considerations of peace and justice to the impulse of any immediate interest or passion.

If the particular States in this country are disposed to stand in a similar relation to each other, and to drop the project of a general DISCRETIONARY SUPERINTENDENCE, the scheme would indeed be pernicious, and would entail upon us all the mischiefs which have been enumerated under the first head; but it would have the merit of being, at least, consistent and practicable Abandoning all views towards a confederate government, this would bring us to a simple alliance offensive and defensive; and would place us in a situation to be alternate friends and enemies of each other, as our mutual jealousies and rivalships, nourished by the intrigues of foreign nations, should prescribe to us.

But if we are unwilling to be placed in this perilous situation; if we still will adhere to the design of a national government, or, which is the same thing, of a superintending power, under the direction of a common council, we must resolve to incorporate into our plan those ingredients which may be considered as forming the characteristic difference between a league and a government; we must extend the authority of the Union to the persons of the citizens, --the only proper objects of government.

Government implies the power of making laws. It is essential to the idea of a law, that it be attended with a sanction; or, in other words, a penalty or punishment for disobedience. If there be no penalty annexed to disobedience, the resolutions or commands which pretend to be laws will, in fact, amount to nothing more than advice or recommendation. This penalty, whatever it may be, can only be inflicted in two ways: by the agency of the courts and ministers of justice, or by military force; by the COERCION of the magistracy, or by the COERCION of arms. The first kind can evidently apply only to men; the last kind must of necessity, be employed against bodies politic, or communities, or States. It is evident that there is no process of a court by which the observance of the laws can, in the last resort, be enforced. Sentences may be denounced against them for violations of their duty; but these sentences can only be carried into execution by the sword. In an association where the general authority is confined to the collective bodies of the communities, that compose it, every breach of the laws must involve a state of war; and military execution must become the only instrument of civil obedience. Such a state of things can certainly not deserve the name of government, nor would any prudent man choose to commit his happiness to it.

There was a time when we were told that breaches, by the States, of the regulations of the federal authority were not to be expected; that a sense of common interest would preside over the conduct of the respective members, and would beget a full compliance with all the constitutional requisitions of the Union. This language, at the present day, would appear as wild as a great part of what we now hear from the same quarter will be thought, when we shall have received further lessons from that best oracle of wisdom, experience. It at all times betrayed an ignorance of the true springs by which human conduct is actuated, and belied the original inducements to the establishment of civil power. Why has government been instituted at all? Because the passions of men will not conform to the dictates of reason and justice, without constraint. Has it been found that bodies of men act with more rectitude or greater disinterestedness than individuals? The contrary of this has been inferred by all accurate observers of the conduct of mankind; and the inference is founded upon obvious reasons. Regard to reputation has a less active influence, when the infamy of a bad action is to be divided among a number than when it is to fall singly upon one. A spirit of faction, which is apt to mingle its poison in the deliberations of all bodies of men, will often hurry the persons of whom they are composed into improprieties and excesses, for which they would blush in a private capacity.

In addition to all this, there is, in the nature of sovereign power, an impatience of control, that disposes those who are invested with the exercise of it, to look with an evil eye upon all external attempts to restrain or direct its operations. From this spirit it happens, that in every political association which is formed upon the principle of uniting in a common interest a number of lesser sovereignties, there will be found a kind of eccentric tendency in the subordinate or inferior orbs, by the operation of which there will be a perpetual effort in each to fly off from the common centre. This tendency is not difficult to be accounted for. It has its origin in the love of power. Power controlled or abridged is almost always the rival and enemy of that power by which it is controlled or abridged. This simple proposition will teach us how little reason there is to expect, that the persons intrusted with the administration of the affairs of the particular members of a confederacy will at all times be ready, with perfect good-humor, and an unbiased regard to the public weal, to execute the resolutions or decrees of the general authority. The reverse of this results from the constitution of human nature.

If, therefore, the measures of the Confederacy cannot be executed without the intervention of the particular administrations, there will be little prospect of their being executed at all. The rulers of the respective members, whether they have a constitutional right to do it or not, will undertake to judge of the propriety of the measures themselves. They will consider the conformity of the thing proposed or required to their immediate interests or aims; the momentary conveniences or inconveniences that would attend its adoption. All this will be done; and in a spirit of interested and suspicious scrutiny, without that knowledge of national circumstances and reasons of state, which is essential to a right judgment, and with that strong predilection in favor of local objects, which can hardly fail to mislead the decision. The same process must be repeated in every member of which the body is constituted; and the execution of the plans, framed by the councils of the whole, will always fluctuate on the discretion of the ill-informed and prejudiced opinion of every part. Those who have been conversant in the proceedings of popular assemblies; who have seen how difficult it often is, where there is no exterior pressure of circumstances, to bring them to harmonious resolutions on important points, will readily conceive how impossible it must be to induce a number of such assemblies, deliberating at a distance from each other, at different times, and under different impressions, long to co-operate in the same views and pursuits.

In our case, the concurrence of thirteen distinct sovereign wills is requisite, under the Confederation, to the complete execution of every important measure that proceeds from the Union. It has happened as was to have been foreseen. The measures of the Union have not been executed; the delinquencies of the States have, step by step, matured themselves to an extreme, which has, at length, arrested all the wheels of the national government, and brought them to an awful stand. Congress at this time scarcely possess the means of keeping up the forms of administration, till the States can have time to agree upon a more substantial substitute for the present shadow of a federal government. Things did not come to this desperate extremity at once. The causes which have been specified produced at first only unequal and disproportionate degrees of compliance with the requisitions of the Union. The greater deficiencies of some States furnished the pretext of example and the temptation of interest to the complying, or to the least delinquent States. Why should we do more in proportion than those who are embarked with us in the same political voyage? Why should we consent to bear more than our proper share of the common burden? These were suggestions which human selfishness could not withstand, and which even speculative men, who looked forward to remote consequences, could not, without hesitation, combat. Each State, yielding to the persuasive voice of immediate interest or convenience, has successively withdrawn its support, till the frail and tottering edifice seems ready to fall upon our heads, and to crush us beneath its ruins.

PUBLIUS.

The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union

For the Independent Journal.

Author: Alexander Hamilton

To the People of the State of New York:

IN THE course of the preceding papers, I have endeavored, my fellow-citizens, to place before you, in a clear and convincing light, the importance of Union to your political safety and happiness. I have unfolded to you a complication of dangers to which you would be exposed, should you permit that sacred knot which binds the people of America together be severed or dissolved by ambition or by avarice, by jealousy or by misrepresentation. In the sequel of the inquiry through which I propose to accompany you, the truths intended to be inculcated will receive further confirmation from facts and arguments hitherto unnoticed. If the road over which you will still have to pass should in some places appear to you tedious or irksome, you will recollect that you are in quest of information on a subject the most momentous which can engage the attention of a free people, that the field through which you have to travel is in itself spacious, and that the difficulties of the journey have been unnecessarily increased by the mazes with which sophistry has beset the way. It will be my aim to remove the obstacles from your progress in as compendious a manner as it can be done, without sacrificing utility to despatch.

In pursuance of the plan which I have laid down for the discussion of the subject, the point next in order to be examined is the "insufficiency of the present Confederation to the preservation of the Union." It may perhaps be asked what need there is of reasoning or proof to illustrate a position which is not either controverted or doubted, to which the understandings and feelings of all classes of men assent, and which in substance is admitted by the opponents as well as by the friends of the new Constitution. It must in truth be acknowledged that, however these may differ in other respects, they in general appear to harmonize in this sentiment, at least, that there are material imperfections in our national system, and that something is necessary to be done to rescue us from impending anarchy. The facts that support this opinion are no longer objects of speculation. They have forced themselves upon the sensibility of the people at large, and have at length extorted from those, whose mistaken policy has had the principal share in precipitating the extremity at which we are arrived, a reluctant confession of the reality of those defects in the scheme of our federal government, which have been long pointed out and regretted by the intelligent friends of the Union.

We may indeed with propriety be said to have reached almost the last stage of national humiliation. There is scarcely anything that can wound the pride or degrade the character of an independent nation which we do not experience. Are there engagements to the performance of which we are held by every tie respectable among men? These are the subjects of constant and unblushing violation. Do we owe debts to foreigners and to our own citizens contracted in a time of imminent peril for the preservation of our political existence? These remain without any proper or satisfactory provision for their discharge. Have we valuable territories and important posts in the possession of a foreign power which, by express stipulations, ought long since to have been surrendered? These are still retained, to the prejudice of our interests, not less than of our rights. Are we in a condition to resent or to repel the aggression? We have neither troops, nor treasury, nor government.["I mean for the Union."] Are we even in a condition to remonstrate with dignity? The just imputations on our own faith, in respect to the same treaty, ought first to be removed. Are we entitled by nature and compact to a free participation in the navigation of the Mississippi? Spain excludes us from it. Is public credit an indispensable resource in time of public danger? We seem to have abandoned its cause as desperate and irretrievable. Is commerce of importance to national wealth? Ours is at the lowest point of declension. Is respectability in the eyes of foreign powers a safeguard against foreign encroachments? The imbecility of our government even forbids them to treat with us. Our ambassadors abroad are the mere pageants of mimic sovereignty. Is a violent and unnatural decrease in the value of land a symptom of national distress? The price of improved land in most parts of the country is much lower than can be accounted for by the quantity of waste land at market, and can only be fully explained by that want of private and public confidence, which are so alarmingly prevalent among all ranks, and which have a direct tendency to depreciate property of every kind. Is private credit the friend and patron of industry? That most useful kind which relates to borrowing and lending is reduced within the narrowest limits, and this still more from an opinion of insecurity than from the scarcity of money. To shorten an enumeration of particulars which can afford neither pleasure nor instruction, it may in general be demanded, what indication is there of national disorder, poverty, and insignificance that could befall a community so peculiarly blessed with natural advantages as we are, which does not form a part of the dark catalogue of our public misfortunes?

This is the melancholy situation to which we have been brought by those very maxims and councils which would now deter us from adopting the proposed Constitution; and which, not content with having conducted us to the brink of a precipice, seem resolved to plunge us into the abyss that awaits us below. Here, my countrymen, impelled by every motive that ought to influence an enlightened people, let us make a firm stand for our safety, our tranquillity, our dignity, our reputation. Let us at last break the fatal charm which has too long seduced us from the paths of felicity and prosperity.

It is true, as has been before observed that facts, too stubborn to be resisted, have produced a species of general assent to the abstract proposition that there exist material defects in our national system; but the usefulness of the concession, on the part of the old adversaries of federal measures, is destroyed by a strenuous opposition to a remedy, upon the only principles that can give it a chance of success. While they admit that the government of the United States is destitute of energy, they contend against conferring upon it those powers which are requisite to supply that energy. They seem still to aim at things repugnant and irreconcilable; at an augmentation of federal authority, without a diminution of State authority; at sovereignty in the Union, and complete independence in the members. They still, in fine, seem to cherish with blind devotion the political monster of an imperium in imperio. This renders a full display of the principal defects of the Confederation necessary, in order to show that the evils we experience do not proceed from minute or partial imperfections, but from fundamental errors in the structure of the building, which cannot be amended otherwise than by an alteration in the first principles and main pillars of the fabric.

The great and radical vice in the construction of the existing Confederation is in the principle of LEGISLATION for STATES or GOVERNMENTS, in their CORPORATE or COLLECTIVE CAPACITIES, and as contradistinguished from the INDIVIDUALS of which they consist. Though this principle does not run through all the powers delegated to the Union, yet it pervades and governs those on which the efficacy of the rest depends. Except as to the rule of appointment, the United States has an indefinite discretion to make requisitions for men and money; but they have no authority to raise either, by regulations extending to the individual citizens of America. The consequence of this is, that though in theory their resolutions concerning those objects are laws, constitutionally binding on the members of the Union, yet in practice they are mere recommendations which the States observe or disregard at their option.

It is a singular instance of the capriciousness of the human mind, that after all the admonitions we have had from experience on this head, there should still be found men who object to the new Constitution, for deviating from a principle which has been found the bane of the old, and which is in itself evidently incompatible with the idea of GOVERNMENT; a principle, in short, which, if it is to be executed at all, must substitute the violent and sanguinary agency of the sword to the mild influence of the magistracy.

There is nothing absurd or impracticable in the idea of a league or alliance between independent nations for certain defined purposes precisely stated in a treaty regulating all the details of time, place, circumstance, and quantity; leaving nothing to future discretion; and depending for its execution on the good faith of the parties. Compacts of this kind exist among all civilized nations, subject to the usual vicissitudes of peace and war, of observance and non-observance, as the interests or passions of the contracting powers dictate. In the early part of the present century there was an epidemical rage in Europe for this species of compacts, from which the politicians of the times fondly hoped for benefits which were never realized. With a view to establishing the equilibrium of power and the peace of that part of the world, all the resources of negotiation were exhausted, and triple and quadruple alliances were formed; but they were scarcely formed before they were broken, giving an instructive but afflicting lesson to mankind, how little dependence is to be placed on treaties which have no other sanction than the obligations of good faith, and which oppose general considerations of peace and justice to the impulse of any immediate interest or passion.

If the particular States in this country are disposed to stand in a similar relation to each other, and to drop the project of a general DISCRETIONARY SUPERINTENDENCE, the scheme would indeed be pernicious, and would entail upon us all the mischiefs which have been enumerated under the first head; but it would have the merit of being, at least, consistent and practicable Abandoning all views towards a confederate government, this would bring us to a simple alliance offensive and defensive; and would place us in a situation to be alternate friends and enemies of each other, as our mutual jealousies and rivalships, nourished by the intrigues of foreign nations, should prescribe to us.

But if we are unwilling to be placed in this perilous situation; if we still will adhere to the design of a national government, or, which is the same thing, of a superintending power, under the direction of a common council, we must resolve to incorporate into our plan those ingredients which may be considered as forming the characteristic difference between a league and a government; we must extend the authority of the Union to the persons of the citizens, --the only proper objects of government.

Government implies the power of making laws. It is essential to the idea of a law, that it be attended with a sanction; or, in other words, a penalty or punishment for disobedience. If there be no penalty annexed to disobedience, the resolutions or commands which pretend to be laws will, in fact, amount to nothing more than advice or recommendation. This penalty, whatever it may be, can only be inflicted in two ways: by the agency of the courts and ministers of justice, or by military force; by the COERCION of the magistracy, or by the COERCION of arms. The first kind can evidently apply only to men; the last kind must of necessity, be employed against bodies politic, or communities, or States. It is evident that there is no process of a court by which the observance of the laws can, in the last resort, be enforced. Sentences may be denounced against them for violations of their duty; but these sentences can only be carried into execution by the sword. In an association where the general authority is confined to the collective bodies of the communities, that compose it, every breach of the laws must involve a state of war; and military execution must become the only instrument of civil obedience. Such a state of things can certainly not deserve the name of government, nor would any prudent man choose to commit his happiness to it.

There was a time when we were told that breaches, by the States, of the regulations of the federal authority were not to be expected; that a sense of common interest would preside over the conduct of the respective members, and would beget a full compliance with all the constitutional requisitions of the Union. This language, at the present day, would appear as wild as a great part of what we now hear from the same quarter will be thought, when we shall have received further lessons from that best oracle of wisdom, experience. It at all times betrayed an ignorance of the true springs by which human conduct is actuated, and belied the original inducements to the establishment of civil power. Why has government been instituted at all? Because the passions of men will not conform to the dictates of reason and justice, without constraint. Has it been found that bodies of men act with more rectitude or greater disinterestedness than individuals? The contrary of this has been inferred by all accurate observers of the conduct of mankind; and the inference is founded upon obvious reasons. Regard to reputation has a less active influence, when the infamy of a bad action is to be divided among a number than when it is to fall singly upon one. A spirit of faction, which is apt to mingle its poison in the deliberations of all bodies of men, will often hurry the persons of whom they are composed into improprieties and excesses, for which they would blush in a private capacity.

In addition to all this, there is, in the nature of sovereign power, an impatience of control, that disposes those who are invested with the exercise of it, to look with an evil eye upon all external attempts to restrain or direct its operations. From this spirit it happens, that in every political association which is formed upon the principle of uniting in a common interest a number of lesser sovereignties, there will be found a kind of eccentric tendency in the subordinate or inferior orbs, by the operation of which there will be a perpetual effort in each to fly off from the common centre. This tendency is not difficult to be accounted for. It has its origin in the love of power. Power controlled or abridged is almost always the rival and enemy of that power by which it is controlled or abridged. This simple proposition will teach us how little reason there is to expect, that the persons intrusted with the administration of the affairs of the particular members of a confederacy will at all times be ready, with perfect good-humor, and an unbiased regard to the public weal, to execute the resolutions or decrees of the general authority. The reverse of this results from the constitution of human nature.

If, therefore, the measures of the Confederacy cannot be executed without the intervention of the particular administrations, there will be little prospect of their being executed at all. The rulers of the respective members, whether they have a constitutional right to do it or not, will undertake to judge of the propriety of the measures themselves. They will consider the conformity of the thing proposed or required to their immediate interests or aims; the momentary conveniences or inconveniences that would attend its adoption. All this will be done; and in a spirit of interested and suspicious scrutiny, without that knowledge of national circumstances and reasons of state, which is essential to a right judgment, and with that strong predilection in favor of local objects, which can hardly fail to mislead the decision. The same process must be repeated in every member of which the body is constituted; and the execution of the plans, framed by the councils of the whole, will always fluctuate on the discretion of the ill-informed and prejudiced opinion of every part. Those who have been conversant in the proceedings of popular assemblies; who have seen how difficult it often is, where there is no exterior pressure of circumstances, to bring them to harmonious resolutions on important points, will readily conceive how impossible it must be to induce a number of such assemblies, deliberating at a distance from each other, at different times, and under different impressions, long to co-operate in the same views and pursuits.

In our case, the concurrence of thirteen distinct sovereign wills is requisite, under the Confederation, to the complete execution of every important measure that proceeds from the Union. It has happened as was to have been foreseen. The measures of the Union have not been executed; the delinquencies of the States have, step by step, matured themselves to an extreme, which has, at length, arrested all the wheels of the national government, and brought them to an awful stand. Congress at this time scarcely possess the means of keeping up the forms of administration, till the States can have time to agree upon a more substantial substitute for the present shadow of a federal government. Things did not come to this desperate extremity at once. The causes which have been specified produced at first only unequal and disproportionate degrees of compliance with the requisitions of the Union. The greater deficiencies of some States furnished the pretext of example and the temptation of interest to the complying, or to the least delinquent States. Why should we do more in proportion than those who are embarked with us in the same political voyage? Why should we consent to bear more than our proper share of the common burden? These were suggestions which human selfishness could not withstand, and which even speculative men, who looked forward to remote consequences, could not, without hesitation, combat. Each State, yielding to the persuasive voice of immediate interest or convenience, has successively withdrawn its support, till the frail and tottering edifice seems ready to fall upon our heads, and to crush us beneath its ruins.

PUBLIUS.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

Patrick Winston: How to Speak

Link to the YouTube page for the video above

This video has excellent advice about giving a talk that I hadn’t heard before.

Grace Wetzel: Orgasmic Inequality

I am not entirely comfortable with talking about sex on this blog, but in this case, it is important for discussing an important dimension of sexism in our society. Grace Wetzel—in her TEDx talk which you can watch above—does an admirable job of driving home the argument that there is orgasmic inequality as a result of inegalitarian attitudes toward women. Here is the argument she makes:

In heterosexual encounters, women experience only about 25% of the encounters.

This is associated with the fact that only 25% of women regularly experience orgasms from penetration without additional clitoral stimulation.

However, it is not due to female orgasms being any more difficult to achieve for women than for men: for both men and women, the average masturbation time to orgasm is 4 minutes.

The fact the orgasm rates for lesbians are almost the same as orgasm rates for men also suggests that there is no great inherent biological difficulty in female orgasm.

Despite oral sex received by women being one activity that is especially helpful for clitoral stimulation and therefore for female orgasm, men receive oral sex much more than women do.

Orgasmic inequality is not confined to being a lower-class phenomenon: orgasmic inequality and the behavioral patterns that lead to it are rife among college students.

Grace discusses many of the gender dynamics that help preserve orgasmic inequality. One telltale sign of the dysfunction in our society that preserves orgasmic inequality is the statistic that more than half of all women have faked an orgasm.

A religious belief that the only purpose of sex is reproduction would reduce the concern about orgasmic inequality, since there wouldn’t be the need for much sex at all, and what sex there was could be quite humdrum and still do the reproductive job. But to the extent that sex also serves the purposes of pleasure and emotional bonding for a couple, mutual satisfaction is quite valuable.

Somewhat relatedly, below is a TEDx talk reporting research indicating that even short-term participation in a peer-support group of other women can improve women’s sexual experience substantially:

Appropriately Dosed Rapamycin and Metformin Can Improve Immune Function and Seem to Be Partial Preventatives for COVID-19

Peter Attia is one of the authorities I turn to for greater understanding of diet and health. His podcast “The Drive” is consistent in its message with what I say on supplysideliberal.com about diet and health, but often gets much more technical than I ever get here and often adds nuance. (As an example of nuance, I now believe, based on listening to Peter Attia that 5-20% of people have their low-density lipoprotein particle number shoot up when they eat a lot of saturated fat and that this minority of people should avoid saturated fat. Relatedly, I also learned that a testing of low-density-lipoprotein particle number is a much better test than low-density-lipoprotein mass tests that are all most of us usually get at the doctor’s office.)

I plan to discuss many of Peter Attia’s podcasts in depth in the future. But I thought the recent podcast above deserved to be highlighted immediately because of its relevance to the current pandemic. Please don’t try to make any use of the implicit suggestion in the title of this blog post without (a) listening to the whole podcast and (b) talking to your doctor (ideally after getting your doctor to listen to the whole podcast). Both rapamycin and metformin are drugs that your doctor should have the authority to give you a prescription for, if warranted. Note that rapamycin has an inverted-U-shaped effect on immune function: a little bit aids immune function but larger doses are routinely used to suppress immune function.

One intriguing thing about rapamycin and metformin in relation to Covid-19 is that (1) the danger of Covid-19 goes up dramatically with age and (1) rapamycin and metformin are some of the best bets Peter Attia knows of for general anti-aging drugs.

Postscript: My son-in-law Erik Berlin is a cofounder of Breaker. Breaker is the best podcast search app in existence on our planet. Try it! You can easily find it free in the app store. I listen to Peter Attia’s podcast using Breaker.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

On Ex-Muslims

I learned a bit more about Islam from Daniel Pipes’s essay “When Muslims Leave the Faith” in the August 6, 2020 Wall Street Journal. One point he makes that I had had some inkling of is that Islam is one of the most dangerous religions to leave:

Overtly apostatizing is a radical act that can lead to execution in some Muslim-majority countries, including Iran. Even in the West, apostates often meet rejection by families and friends that can turn violent.

Daniel also cites the following interesting statistics:

There are about 3.5 million Muslims in the U.S., according to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey. The data suggests that about 100,000 of them abandon Islam each year, while roughly the same number convert to Islam. Altogether nearly a quarter of those raised in the faith have left, with Iranians disproportionately represented. Similar trends prevail in Western Europe, where conversions in and out of Islam appear roughly to balance out.

In the U.S., ex-Muslims’ motives for leaving vary. Asked what their “main reason” was for no longer identifying as Muslim, Pew found 25% had general issues with religion and 19% with Islam in particular. Some 16% said they prefer another religion, and 14% cited “personal growth.” More than half of them abandon religion entirely, and 22% now identify as Christian.

There have been some efforts by ex-Muslims to support other ex-Muslims:

The activists Nonie Darwish and Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote books about becoming “infidels.” …

Some ex-Muslims living in the West do something inconceivable in Muslim-majority countries: They publicly organize against Islam in dozens of groups like Germany’s Central Council of Ex-Muslims and Ms. Darwish’s Former Muslims United. Such organizations also provide mutual support in the face of intense hostility and raise troublesome issues—with female genital mutilation among the most prominent in recent years—thereby becoming some of the most credible critics of Islamism.

Other than the threat of death for ex-Muslims and the threat of female genital mutilation for current Muslims, all of this is familiar to me from what happens with ex-Mormons, who do a fair amount to support one another.

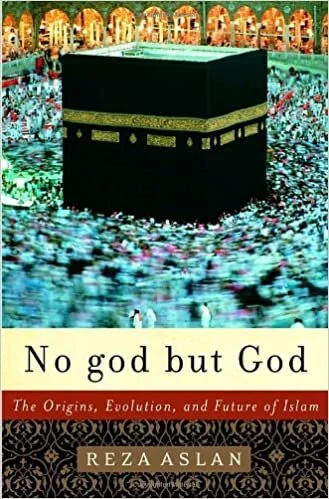

One book-writing ex-Muslim Daniel Pipes fails to mention is Reza Aslan, who has writing a book about the past, present and future of Islam:

I ran into this book by accident (or by the design of Amazon’s algorithm) this past week and put it on my book wishlist. (I have a deal with myself that if I list a book on an Excel file I have that I can buy it as soon as I will actually sit down to begin reading it. This is a big help in reducing how much I spend on books.)

Note: I have a tag “religionhumanitiesscience” that will get you to my posts on religion and my posts on political philosophy. If you click on the link on this sentence, that will also take you there.

100 Economics Blogs and 100 Economists Who Are Influential Online

I am pleased to have this blog listed again as one of the Top 100 Economics Blogs by the Intelligent Economist and to have Richtopia list me as one of the top 100 most economists most influential online. I try hard not to let desire for rank cause me to sacrifice anything else important, but I like high rank :) You do too ;)

If you want, you can see more purely academic indications of rank for me in this post. The numbers fluctuate from month to month, but by REPEC’s overall ranking, with rounding, I am roughly the 450th highest ranked economist in the world and I am roughly 250th by fully-adjusted citations (“Number of Citations, Weighted by Number of Authors and Recursive Impact Factors, Discounted by Citation Age”). Currently, I am listed by REPEC as 121st economist in number of Twitter followers.

I am currently 79th on REPEC in “Breadth of citations across fields.” I like this because I see myself as interested in almost everything in economics, as well as many, many things that are outside of economics as its boundaries are conventionally understood. (But see “Economics Needs to Tackle All of the Big Questions in the Social Sciences” and “Defining Economics.” I would love to see “economic imperialism” extend to nutrition, as you can gather from reading my diet and health posts.)

Don't Drink Sweet Drinks Between Meals—Whether Sugary or with Nonsugar Sweeteners

For the bottom line of this post, you may want to jump to the Conclusion. Everything else is about backing up that advice.

Existing research doesn’t tell us as much about the effects of nonsugar sweeteners as one would like. But “Effects of aspartame-, monk fruit-, stevia- and sucrose-sweetened beverages on postprandial glucose, insulin and energy intake” by S L Tey, N B Salleh, J Henry, and C G Forde gives some hint that using nonsugar sweeteners as part of a substantial meal or snack is better than using nonsugar sweeteners in a zero-calorie beverage consumed as a snack on its own.

To be more precise, consuming a beverage on its own with a nonsugar sweetener seems to lead to people eating enough more that it doesn’t reduce overall calorie intake, blood glucose levels or blood insulin levels overall below what would happen if one consumed a sugary beverage. By contrast, using a nonsugar sweetener instead of sugar as part of a substantial snack seems to help in reducing overall calorie intake.

The introduction to the paper shown above reports on an experiment in which nonsugar sweeteners were part of a substantial snack:

To date, only one study has investigated the effects of artificial and natural NNS on food intake, postprandial glucose and insulin. This randomised crossover study utilised a double preload design to compare the effects of consuming two preloads of crackers and cream cheese sweetened with sucrose (986 kcal), aspartame (580 kcal) or stevia (580 kcal); one before lunch and one before dinner, on energy intake, postprandial glucose and insulin concentrations. Daily energy intake was significantly lower when participants consumed preloads with aspartame and stevia, compared with a sucrose preload. stevia preload also showed additional benefit of lowering postprandial blood glucose and insulin concentrations, compared with aspartame and sucrose preloads. However, it is unknown whether the beneficial effect of stevia can be generalised to monk fruit and also whether the same result can be obtained if the preload contains no calories, for example, diet beverage.

The conclusion of the paper shown above contrasts the results from a nonsugar sweetener instead of sugar as part of a substantial snack and the results from a nonsugar sweetener instead of sugar as part of a standalone beverage snack. As part of a standalone beverage snack, the zero-calorie beverage with a nonsugar sweetener left calorie intake, overall glucose level and overall insulin level in the same ballpark as an otherwise similar sugar-sweetened beverage:

… when participants consumed a preload of crackers with cream cheese sweetened with NNS, 20 min before lunch, postprandial glucose concentration following lunch was significantly lower with NNS compared with a preload sweetened with sucrose. Overall, the evidence seems to suggest that consuming NNS alone without any energy (empty calorie) before a meal may lead to larger spikes in glucose and insulin responses after the meal. The preload used in the current study resembles a pre-meal beverage such as a mid-morning sugar-sweetened beverage before lunch or a midafternoon soft drink before dinner

Conclusion: My advice is to not use sugar at all (see “Sugar as a Slow Poison” and “Letting Go of Sugar”) and only use nonsugar sweeteners as part of a meal or a substantial snack. Note also that juice counts as a sugar-sweetened drink—something to be avoided entirely. (Juice is much worse than whole fruit. See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.”)

On the question of which nonsugar sweeteners to choose as part of a meal or substantial snack, see “Which Nonsugar Sweeteners are OK? An Insulin-Index Perspective.”

What to Drink Instead: Avoiding sweet drinks between meals doesn’t mean you have to drink plain water. Unsweetened coffee and tea (or perhaps minimally sweetened coffee or tea) do not have the problem sweet drinks have. Carbonated water, as from SodaStream or one of its competitors is great. And there is now a huge variety of flavored sparkling water. On that, see my post “In Praise of Flavored Sparkling Water” where I mention some of my favorites. (New varieties keep appearing so I may need to write another review of flavored sparkling water sometime.)

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

James Madison is incisive in his arguments in his numbers of the Federalist Papers. In the Federalist Papers #14, he argues that the United States would not be to large to be governed to a Congress of representatives meeting in one place. To show how he makes his argument, let me add my own summary headings in bold italics to James Madison’s text:

FEDERALIST NO. 14

Objections to the Proposed Constitution From Extent of Territory Answered

From the New York Packet

Friday, November 30, 1787.

Author: James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

Thesis statement: The supposed difficulties of governing a territory even as large in extent as the Union are imaginary.

WE HAVE seen the necessity of the Union, as our bulwark against foreign danger, as the conservator of peace among ourselves, as the guardian of our commerce and other common interests, as the only substitute for those military establishments which have subverted the liberties of the Old World, and as the proper antidote for the diseases of faction, which have proved fatal to other popular governments, and of which alarming symptoms have been betrayed by our own. All that remains, within this branch of our inquiries, is to take notice of an objection that may be drawn from the great extent of country which the Union embraces. A few observations on this subject will be the more proper, as it is perceived that the adversaries of the new Constitution are availing themselves of the prevailing prejudice with regard to the practicable sphere of republican administration, in order to supply, by imaginary difficulties, the want of those solid objections which they endeavor in vain to find.

Republics rely on representatives; they can operate well over much larger geographical regions than direct democracies where the bulk of the citizens meet in person.

The error which limits republican government to a narrow district has been unfolded and refuted in preceding papers. I remark here only that it seems to owe its rise and prevalence chiefly to the confounding of a republic with a democracy, applying to the former reasonings drawn from the nature of the latter. The true distinction between these forms was also adverted to on a former occasion. It is, that in a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person; in a republic, they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents. A democracy, consequently, will be confined to a small spot. A republic may be extended over a large region.

Monarchist writers tend to lump republics and direct democracies together—and choose troubled examples.

To this accidental source of the error may be added the artifice of some celebrated authors, whose writings have had a great share in forming the modern standard of political opinions. Being subjects either of an absolute or limited monarchy, they have endeavored to heighten the advantages, or palliate the evils of those forms, by placing in comparison the vices and defects of the republican, and by citing as specimens of the latter the turbulent democracies of ancient Greece and modern Italy. Under the confusion of names, it has been an easy task to transfer to a republic observations applicable to a democracy only; and among others, the observation that it can never be established but among a small number of people, living within a small compass of territory.

America’s republic would be a new type of thing, so old, failed examples do not apply.

Such a fallacy may have been the less perceived, as most of the popular governments of antiquity were of the democratic species; and even in modern Europe, to which we owe the great principle of representation, no example is seen of a government wholly popular, and founded, at the same time, wholly on that principle. If Europe has the merit of discovering this great mechanical power in government, by the simple agency of which the will of the largest political body may be concentred, and its force directed to any object which the public good requires, America can claim the merit of making the discovery the basis of unmixed and extensive republics. It is only to be lamented that any of her citizens should wish to deprive her of the additional merit of displaying its full efficacy in the establishment of the comprehensive system now under her consideration.

The Continental Congress hasn’t been troubled by a lack of attendance by representatives from the more distant states.

As the natural limit of a democracy is that distance from the central point which will just permit the most remote citizens to assemble as often as their public functions demand, and will include no greater number than can join in those functions; so the natural limit of a republic is that distance from the centre which will barely allow the representatives to meet as often as may be necessary for the administration of public affairs. Can it be said that the limits of the United States exceed this distance? It will not be said by those who recollect that the Atlantic coast is the longest side of the Union, that during the term of thirteen years, the representatives of the States have been almost continually assembled, and that the members from the most distant States are not chargeable with greater intermissions of attendance than those from the States in the neighborhood of Congress.

The United States, between the Atlantic and the Mississippi, is not much larger than some European nations that have an effective assembly of representatives.

That we may form a juster estimate with regard to this interesting subject, let us resort to the actual dimensions of the Union. The limits, as fixed by the treaty of peace, are: on the east the Atlantic, on the south the latitude of thirty-one degrees, on the west the Mississippi, and on the north an irregular line running in some instances beyond the forty-fifth degree, in others falling as low as the forty-second. The southern shore of Lake Erie lies below that latitude. Computing the distance between the thirty-first and forty-fifth degrees, it amounts to nine hundred and seventy-three common miles; computing it from thirty-one to forty-two degrees, to seven hundred and sixty-four miles and a half. Taking the mean for the distance, the amount will be eight hundred and sixty-eight miles and three-fourths. The mean distance from the Atlantic to the Mississippi does not probably exceed seven hundred and fifty miles. On a comparison of this extent with that of several countries in Europe, the practicability of rendering our system commensurate to it appears to be demonstrable. It is not a great deal larger than Germany, where a diet representing the whole empire is continually assembled; or than Poland before the late dismemberment, where another national diet was the depositary of the supreme power. Passing by France and Spain, we find that in Great Britain, inferior as it may be in size, the representatives of the northern extremity of the island have as far to travel to the national council as will be required of those of the most remote parts of the Union.

Those matters of government that most require proximity are still the business of the individual states; the federal government is only dealing with enumerated issues.

Favorable as this view of the subject may be, some observations remain which will place it in a light still more satisfactory.

In the first place it is to be remembered that the general government is not to be charged with the whole power of making and administering laws. Its jurisdiction is limited to certain enumerated objects, which concern all the members of the republic, but which are not to be attained by the separate provisions of any. The subordinate governments, which can extend their care to all those other subjects which can be separately provided for, will retain their due authority and activity. Were it proposed by the plan of the convention to abolish the governments of the particular States, its adversaries would have some ground for their objection; though it would not be difficult to show that if they were abolished the general government would be compelled, by the principle of self-preservation, to reinstate them in their proper jurisdiction.

Let the future worry about how to govern when there is further expansion of the United States.

A second observation to be made is that the immediate object of the federal Constitution is to secure the union of the thirteen primitive States, which we know to be practicable; and to add to them such other States as may arise in their own bosoms, or in their neighborhoods, which we cannot doubt to be equally practicable. The arrangements that may be necessary for those angles and fractions of our territory which lie on our northwestern frontier, must be left to those whom further discoveries and experience will render more equal to the task.

Note that in the future, there will be more and better roads and canals.

Let it be remarked, in the third place, that the intercourse throughout the Union will be facilitated by new improvements. Roads will everywhere be shortened, and kept in better order; accommodations for travelers will be multiplied and meliorated; an interior navigation on our eastern side will be opened throughout, or nearly throughout, the whole extent of the thirteen States. The communication between the Western and Atlantic districts, and between different parts of each, will be rendered more and more easy by those numerous canals with which the beneficence of nature has intersected our country, and which art finds it so little difficult to connect and complete.

The most distant states might be thought to complain most about having to send representatives a long way, but they are also likely to be, in some sense, border states, who benefit greatly from being part of the Union. So they will be less likely to complain than the distance by itself might suggest.

A fourth and still more important consideration is, that as almost every State will, on one side or other, be a frontier, and will thus find, in regard to its safety, an inducement to make some sacrifices for the sake of the general protection; so the States which lie at the greatest distance from the heart of the Union, and which, of course, may partake least of the ordinary circulation of its benefits, will be at the same time immediately contiguous to foreign nations, and will consequently stand, on particular occasions, in greatest need of its strength and resources. It may be inconvenient for Georgia, or the States forming our western or northeastern borders, to send their representatives to the seat of government; but they would find it more so to struggle alone against an invading enemy, or even to support alone the whole expense of those precautions which may be dictated by the neighborhood of continual danger. If they should derive less benefit, therefore, from the Union in some respects than the less distant States, they will derive greater benefit from it in other respects, and thus the proper equilibrium will be maintained throughout.

It is a noble thing to do something new. Conversely, a rule that says we can only do what has been done before would hamstring us.

I submit to you, my fellow-citizens, these considerations, in full confidence that the good sense which has so often marked your decisions will allow them their due weight and effect; and that you will never suffer difficulties, however formidable in appearance, or however fashionable the error on which they may be founded, to drive you into the gloomy and perilous scene into which the advocates for disunion would conduct you. Hearken not to the unnatural voice which tells you that the people of America, knit together as they are by so many cords of affection, can no longer live together as members of the same family; can no longer continue the mutual guardians of their mutual happiness; can no longer be fellowcitizens of one great, respectable, and flourishing empire. Hearken not to the voice which petulantly tells you that the form of government recommended for your adoption is a novelty in the political world; that it has never yet had a place in the theories of the wildest projectors; that it rashly attempts what it is impossible to accomplish. No, my countrymen, shut your ears against this unhallowed language. Shut your hearts against the poison which it conveys; the kindred blood which flows in the veins of American citizens, the mingled blood which they have shed in defense of their sacred rights, consecrate their Union, and excite horror at the idea of their becoming aliens, rivals, enemies. And if novelties are to be shunned, believe me, the most alarming of all novelties, the most wild of all projects, the most rash of all attempts, is that of rendering us in pieces, in order to preserve our liberties and promote our happiness. But why is the experiment of an extended republic to be rejected, merely because it may comprise what is new? Is it not the glory of the people of America, that, whilst they have paid a decent regard to the opinions of former times and other nations, they have not suffered a blind veneration for antiquity, for custom, or for names, to overrule the suggestions of their own good sense, the knowledge of their own situation, and the lessons of their own experience? To this manly spirit, posterity will be indebted for the possession, and the world for the example, of the numerous innovations displayed on the American theatre, in favor of private rights and public happiness. Had no important step been taken by the leaders of the Revolution for which a precedent could not be discovered, no government established of which an exact model did not present itself, the people of the United States might, at this moment have been numbered among the melancholy victims of misguided councils, must at best have been laboring under the weight of some of those forms which have crushed the liberties of the rest of mankind. Happily for America, happily, we trust, for the whole human race, they pursued a new and more noble course. They accomplished a revolution which has no parallel in the annals of human society. They reared the fabrics of governments which have no model on the face of the globe. They formed the design of a great Confederacy, which it is incumbent on their successors to improve and perpetuate. If their works betray imperfections, we wonder at the fewness of them. If they erred most in the structure of the Union, this was the work most difficult to be executed; this is the work which has been new modelled by the act of your convention, and it is that act on which you are now to deliberate and to decide.

PUBLIUS.

Here are links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government